Abstract

Background

Income inequality has been linked to health and mortality. While there has been extensive research exploring the relationship, the evidence for whether the relationship is causal remains disputed. We describe the methods for a systematic review that will transparently assess whether a causal relationship exists between income inequality and mortality and self-rated health.

Methods

We will identify relevant studies using search terms relating to income inequality, mortality, and self-rated health (SRH). Four databases will be searched: MEDLINE, ISI Web of Science, EMBASE, and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The inclusion criteria have been developed to identify the study designs best suited to assess causality: multilevel studies that have conditioned upon individual income (or a comparable measure, such as socioeconomic position) and natural experiment studies. Risk of bias assessment of included studies will be conducted using ROBINS-I. Where possible, we will convert all measures of income inequality into Gini coefficients and standardize the effect estimate of income inequality on mortality/SRH. We will conduct random-effects meta-analysis to estimate pooled effect estimates when possible. We will assess causality using modified Bradford Hill viewpoints and assess certainty using GRADE.

Discussion

This systematic review protocol lays out the complexity of the relationship between income inequality and individual health, as well as our approach for assessing causality. Understanding whether income inequality impacts the health of individuals within a population has major policy implications. By setting out our methods and approach as transparently as we can, we hope this systematic review can provide clarity to an important topic for public policy and public health, as well as acting as an exemplar for other “causal reviews”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

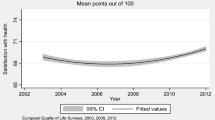

Income inequality refers to the uneven distribution of income between people, assessed across regions, states, or countries [1, 2]. It is generally agreed that income inequality is associated with health outcomes at an ecological level. Our focus is on the more disputed hypothesis that after accounting for the impact of individual income, there is a relationship between income inequality and health [3]. This relationship is of great interest to public health and policymakers [3,4,5], though research evaluating the relationship has produced mixed results [6]. A recent systematic review of reviews evaluating the relationship between income inequality and health found considerable variation in the findings of thirteen systematic reviews, none of which were considered high-quality [2]. The extensive statistical heterogeneity observed by these reviews indicates that a causal relationship between income inequality and individual health remains unconfirmed. Understanding reasons for different effect estimates observed across studies (i.e. statistical heterogeneity or transportability as it is known in causal inference) is an important part of causal assessment [7, 8].

Systematic reviews, because of the scientific approach to selecting, appraising, and synthesising evidence, are useful for transparently bringing together a relevant body of evidence, evaluating statistical heterogeneity, and critically assessing risks of bias [9, 10]. A rigorous, systematic, and transparent evaluation of the evidence and causality is necessary to be certain of the relationship between income inequality and health, which can then clarify the need for policymakers to intervene on the exposure [11, 12]. The meta-analysis by Kondo and colleagues [13], though it was considered the highest quality identified in the review of reviews and incorporated multilevel data, did not include a critical appraisal of the literature nor assess the certainty of their findings (e.g. via a GRADE assessment). Pickett and Wilkinson [14] (also included in the review of reviews [2]) incorporated Bradford Hill viewpoints to their review assessing the relationship between income inequality and mortality. However, they also did not use a systematic approach to searching, identifying, analysing, evaluating, and synthesising evidence. Thus, we have not identified reviews that have incorporated a rigorous and robust systematic review process that incorporates causal assessment.

Income inequality and health

Early understanding of the relationship between income inequality and health was largely based on ecological studies [15,16,17]. The unit of analysis in these early studies was populations (usually countries or states), and though it is not described in this way, these studies also appear to argue that the relationship between income inequality and aggregate health is confounded by country/state-level income (e.g. GDP, GDP per capita). The directed acyclic graph (DAG)Footnote 1 in Fig. 1 illustrates this relationship. There is a theorized non-linear relationship between previous area-level income and current aggregate health such that increasing area-level income increases aggregate health until a threshold where area-level income has no effect on aggregate health [20].

Area-level income confounding

Many ecological studies (and reviews of income inequality and health) address area-level income confounding (including related concepts such as GDP) by limiting the analysis to high-income countries (HIC) [16, 17] though it may not be appropriate to do so. These early ecological studies argued that the effect of area-level income confounding is hypothesized to be greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) than in HIC [3]. However, recent evidence suggests the effect may be comparable in both HIC and LMIC [21]. In addition, considering the effect of income inequality on individual health in only HIC limits our understanding of the effect of income inequality on individual health in LMIC [22]. The extent to which area-level income is a confounding variable has also been debated. According to political economy theory, governmental policies affect income inequality which in turn affects future economic growth, regardless of the baseline level of inequality prior to government actions [23]. Economic growth affects current area-level income, such that area-level income may mediate the relationship between income inequality and aggregate health. However, the putative effect of income inequality on economic growth may depend on relative area-level income; the inverted-U hypothesis (known as the Kuznets curve [24]) suggests that the relationship between economic growth and income inequality is positive in LMIC and negative in HIC [25]. The empirical evidence regarding both the direction [25,26,27] and the sign of the relationship between income inequality and economic growth is mixed, with some arguing that the latter may be impacted by many other factors such as technological advancements [23, 25]. Thus, there is disagreement over the appropriateness of conditioning upon area-level income is an over-adjustment if it is a mediator rather than a confounder [22, 27].

Individual income confounding

With all other things being equal, a country with high-income inequality will likely have more low-income individuals (including a greater number of people in poverty i.e. falling substantially below the median income [28]) than a country with low-income inequality. The country with more low-income individuals will have disproportionally worse population health outcomes than the country with fewer low-income individuals. That is, the relationship between income inequality and individual health could entirely be explained by individual incomes [29]. Individual health, which has a non-linear relationship with individual income where the benefit of income for individual health depreciates with increasing income (known as the absolute income hypothesis) [30]. In other words, a £100 increase of income for low-income individuals (e.g. from £1000 to £1100) will produce a greater increase in health than a £100 increase for high-income individuals (e.g. from £100,000 to £100,100) [29]. Thus, individual income is a cross-level confounding variable [31] since it affects both the ecological exposure (i.e. income inequality is derived from individual incomes) and the individual-level outcome (individual-level health) [32] (see Fig. 2). Multilevel data, which include both aggregate- and individual-level variables, are necessary to disentangle the impact of individual income on income inequality and health and to evaluate the potential causal link [33].

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) illustrating cross-level confounding of an individual’s income on the relationship between income inequality and individual health, annotated with subscript t to account for time. Area-level variables (e.g. income inequality, X) are capitalized while individual-level variables are lower-cased (e.g. individual-level income i) [31]. Individual income should be conditioned upon (represented by the square around individual-level income) to remove the confounding effect of individual income on the relationship between income inequality and individual health

What is the mechanism by which income inequality causes individual health?

The psychosocial and neo-material frameworks offer two different, and often polarizing, explanations for the mechanisms through which income inequality affects individual health [5, 34]. While these frameworks are positioned as competing explanations [34], it is unlikely that either framework perfectly describes the mechanism between income inequality and individual health. While our systematic review does not aim to examine mechanisms, these can offer insight into the debate over which variables should be conditioned upon in any analysis. We use DAGs to articulate the different explanatory mechanisms described by each of these frameworks as they relate to our unit of analysis, individual health. Importantly, the DAGs are based both on our interpretation of key texts relating to each framework as well as our current understanding of the relationship structures. These frameworks were likely not written with causal thinking, as we know it today, in mind and thus illustrating these mechanisms through DAGs may not reflect the frameworks as they were originally intended.

Psychosocial framework

According to the psychosocial framework (popularized by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in their book, The Spirit Level [35]), social status and hierarchies amongst individuals are more noticeable in countries with high-income inequality than in those with less income inequality [36]. Income inequality leads to social differentiation and comparisons, which has adverse psychological consequences (e.g. reduced social cohesion and trust; stress from comparing yourself to people who have more incomes and material goods; frustration and despair that could lead to crime and violence) which in turn negatively affects health [37,38,39]. The heightened awareness of hierarchy in high-income inequality societies is also hypothesized to impact individual behaviour, such that attenuated social cohesion increases the likelihood that individuals will smoke, consume alcohol and have diets that increase their risk of mortality [36]. The relationship between income inequality, psychosocial factors (such as social cohesion and behaviour), mortality, and individual income is summarized in Fig. 3.

Direct acyclic graph (DAG) illustrating the relationship between income inequality and individual health mediated by psychosocial factors and confounded by individual income. Subscript t indicates time while area-level variables are capitalized and individual-level variables are lower-cased. This DAG reflects our general understanding of the psychosocial literature and is not intended to reflect the framework as described by any individuals [35]. According to the literature, psychosocial factors are theorized to mediate the effect of income inequality. Individual income is theorized to be a proxy for socioeconomic position, and some argue that conditioning upon individual income may be an over- adjustment that will underestimate the effect of income inequality on health. However, particularly as our outcome under study is individual health, we argue that individual income will not completely account for the individual social position (hence the line from individual income to psychosocial factors) and should be conditioned upon

As noted above, this DAG was developed to reflect how the psychosocial framework may be applied to our unit of analysis and our understanding of the impact of individual income on the relationship, and as a result, slightly diverges from some key elements of the original framework. Firstly, the outcome under study here is individual health, not aggregate health as originally described [38, 40]. Wilkinson, both in his early work on income inequality and life expectancy [17] and in his later work with Pickett when the psychosocial framework was formalized, has been criticized [41,42,43] for relying on ecological studies to make assumptions about individual health. They both disputed this claim and insisted that findings from ecological studies were only used to understand the relationship between income inequality and population health [14, 44].

The second key element of the psychosocial framework altered in our DAG is conditioning upon individual income. The psychological framework posits that individual income should not be conditioned upon, even if the unit of analysis is individual health, because it is a proxy for psychosocial consequences of social differentiation and comparison (which mediate rather than confound the relationship between income inequality and health) [44]. However, we argue that individual incomes (and other socio-economic characteristics such as socioeconomic position (SEP)) are poor proxies for psychosocial factors and should be conditioned upon as candidate confounders (as has been done in several studies [45,46,47] and reviews [13, 48]).

Neo-material framework

The neo-material framework hypothesizes that political and economic actions affect income inequality and public resources, such that individuals with fewer resources are disproportionately disadvantaged in countries with high-income inequality [5]. Political and economic actions can include taxes, cash transfers, political structure, and power of organized labour. In our interpretation of early work on the neo-material framework [5] (see Fig. 4), political and economic factors are an upstream confounder of the relationship between income inequality and individual health and while individual income is also a confounder, it is downstream of political and economic factors. In addition to income inequality, political and economic factors affect both public service provisions (on the pathways between income inequality and health) and individual income (e.g. cash transfers). The neo-material framework highlights why time lags may be necessary to understand the effect of income inequality on individual health [3]. For example, it may take as much as fifteen years [49] for the effect of limiting organized labour’s power to increase income inequality and adversely impact health.

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) of the simplified relationship between income inequality and individual health, confounded by individual income, political and economic factors and mediated by public service provisions. Time is indicated with a subscript t while area-level variables are capitalized and individual-level variables are lower-cased. This DAG reflects our general understanding of the neo-material literature, though the structure of the relationship (including whether public service provisions are a co-exposure and thus should be conditioned upon, not shown) remains debated

We also argue that political and economic actions can modify the effect of income inequality on individual health through public service provisions (e.g. strength labour unions to improve access to healthcare). However, it is important to note that the interpretation in Fig. 4 may not accurately represent the relationship; it may be that public service provisions are co-exposures of individual health and occur alongside income inequality [50] (i.e. without the arrow to income inequality shown in the DAG).

Methods

Information in this systematic review protocol is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [51]. The systematic review was submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42021252791) and any subsequent amendments to the protocol will be documented and published in the systematic review.

Aims and objectives

The main aims of the systematic review are to understand if there is a relationship between income inequality and individual mortality and/or SRH, and, if so, if that relationship is causal. While our aims do not include understanding the putative causal mechanism, we will consider evidence of a causal mechanism to strengthen our certainty that a causal relationship exists. To address these aims, we will attempt to address the following questions:

-

1.

What evidence is there of a relationship between income inequality and individual mortality and/or SRH?

-

2.

What is the magnitude of the association between income inequality and individual mortality and/or SRH?

-

3.

To what extent does the available evidence support a causal relationship between income inequality and individual mortality/SRH?

Study design

To answer our research questions, this systematic review will incorporate approaches to causal assessment. We will apply adapted Bradford Hill viewpoints where two viewpoints (coherence and analogy) have been excluded. Our interpretation and approach to applying the viewpoints, including which viewpoints to use, is based on earlier research comparing different approaches to causal assessment [52] and a scoping review of causal systematic reviews (unpublished). These interpretations were used to inform our search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria. The viewpoints, their interpretation, and the evidence we will use to determine if a viewpoint is met are in Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for our review are summarized in Table 2.

Search, screening, data extraction, and critical appraisal

Search strategy

We developed our search strategy with the support of an information scientist. Our strategy was based on two categories of keywords: income inequality (e.g. “income”, “inequality”, “income inequality”, “Gini”) and health (e.g. “mortality”, “all-cause”, “life-expectancy”, “death”, and “health”). We will search MEDLINE, ISI Web of Science, EMBASE, and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The search strategy is in Appendix. We do not plan to search grey literature but references in all included studies will be checked to retrieve any additional articles missed by our search strategy.

Study selection process

Studies identified from the search will be imported into Covidence where they will be assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. One reviewer (MS) will screen all titles to identify and exclude references that obviously do not meet both the exposure and outcome criteria. An initial “title only” screening is a time-efficient approach that is unlikely to affect the amount of relevant included studies [59]. Subsequently, two reviewers will independently screen titles and abstracts of all remaining references. Studies will be included if the study design is unclear but all other criteria are met. Of those that potentially meet the inclusion criteria, full-texts will be identified and independently screened by two reviewers. The reasons for excluding full-text studies will be recorded and a third reviewer will resolve disagreements.

Data extraction

One reviewer will extract data from included studies. A second reviewer will check all of the extracted data. We will extract study information, the indicators used to measure income inequality and morality/SRH and baseline information in the population include sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and age. We will note if the studies explain why certain variables were conditioned upon. A sample data extraction form is provided in Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers will independently assess the included studies for bias using the ROBINS-I tool for observational data [60]. For ROBINS-I, we have developed a target trial that considers exposures, comparisons, confounding, and co-exposures. Confounding variables are those that cause both the exposure and outcome under study, while co-exposures are those that may be received alongside the exposure understudy and may be associated with (though not necessarily the cause of) the exposure and outcome under study [60]. This is helpful when considering if studies conditioned upon variables that we have considered mediators (and should not be conditioned upon) and those that we have considered confounding variables (and should be conditioned upon) [61]. Though ROBINS-I has been criticized for low interrater reliability [62] and is often misapplied [63], it facilitates thorough and systematic methodological evaluation of non-randomized studies using principles of causal thinking [64]. This methodological evaluation will be used to inform considerations of certainty through GRADE and causal assessment using the adapted Bradford Hill viewpoints.

Strategy for synthesis and causal analysis

Our method for data analysis includes both a meta-analysis as well as causal analysis. As it is unlikely we will be able to test for political and economic factors, we will narratively describe the differences across the included studies.

Meta-analysis

We will conduct a meta-analysis to determine the overall association between income inequality and mortality as well as a separate meta-analysis of and income inequality and SRH. Where possible, we will synthesize the outcome measures for mortality (mortality rates, life-expectancy) and SRH (SRH, wellbeing). All meta-analyses will be random-effects, given the considerable heterogeneity expected across contexts, study designs, and populations. If possible, we will convert all of the indicators into Gini coefficients and standardize the effect estimate of income inequality on mortality/SRH. as this is likely to be the most commonly used indicator for income inequality [13]. In addition, we will explore factors we believe may account for statistical heterogeneity (see Table 4) as part of understanding the causal relationship.

GRADE

We will perform a GRADE assessment, a widely adopted approach for assessing the certainty of evidence across a body of evidence, on both outcomes (mortality and SRH) [65]. The GRADE assessment of certainty, which describes the confidence in the effect estimates [65] is based on the assessment of risk of bias [66], indirectness of included evidence [67], imprecision [68], inconsistency [69], and publication bias across the body of evidence [70]. Certainty from non-randomized studies (NRS), which are the most likely types of studies included in this review, are automatically rated at the same level (“high”) as randomized controlled trials when using ROBINS-I, and then subject to downgrading based on a set of domains [71]. Large associations, dose-response relationships, and adjusting for plausible confounding upgrade certainty of the evidence for NRSs.

Causal assessment

We will assess the studies to explore the causal relationship between the income inequality and mortality. Table 1 provides an overview of the evidence we will consider for each Bradford Hill viewpoint. Together with the meta-analysis, we will narratively describe our confidence, based on the evidence, that there is a relationship between income inequality and individual health and our confidence that it is causal.

Conclusion

This protocol describes the methods for conducting a causal systematic review on income inequality and individual health. In the first section, we highlighted the debate over the nature of the relationship and explain consequences for observed associations. While testing the two explanatory, and often competing, mechanisms are beyond the scope of this systematic review, we are explicitly favouring the neo-material framework by both including multilevel studies that condition upon individual income and considering political and economic factors as co-exposures. We expect the complexities of standardising and synthesising evidence from a wide range of studies using different income inequality measurements and statistical methods to be amongst the most challenging aspect of this review. We hope this review will not only elucidate the relationship between income inequality and health but also act as an exemplar for transparently performing causal assessment in evidence synthesis.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

Our DAGs are purposefully simplified and are not likely to capture the complexity of the relationships under study. DAG do not illustrate relationship signs (e.g. positive vs negative), magnitudes (e.g. effect sizes), or shapes (e.g. linear, monotonic) [18]. Moreover, as DAGs do not illustrated cyclical relationships [19], variables are annotated with a subscript of t to indicate time points to distinguish the time when variables are observed.

References

Andreas B, Therese N, Daniel W. Income inequality and health: what does the literature tell us? Sick of inequality? An introduction to the relationship between inequality and health. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2016.

McCartney G, Hearty W, Arnot J, Popham F, Cumbers A, McMaster R. Impact of political economy on population health: a systematic review of reviews. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(6):E1–E12.

Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, Hillemeier M, Ross N, Kaplan GA, et al. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q. 2004;82(1):5–99.

Curran M, Mahutga MC. Income inequality and population health: a global gradient? J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(4):536–53.

Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320(7243):1200–4.

O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Van Ourti T. Chapter 17 - Health and inequality. In: Atkinson AB, Bourguignon F, editors. Handbook of Income Distribution. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. p. 1419–533.

Weed DL. Interpreting epidemiological evidence: how meta-analysis and causal inference methods are related. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):387–90.

Weed DL. Meta-analysis and causal inference: a case study of benzene and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(5):347–55.

Khan KS, Ball E, Fox CE, Meads C. Systematic reviews to evaluate causation: an overview of methods and application. Evid Based Med. 2012;17(5):137–41.

Colditz GA, Burdick E, Mosteller F. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis of data from epidemiologic studies: a commentary. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(4):371–82.

Hernán MA. The C-Word: scientific euphemisms do not improve causal inference from observational data. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(5):616–9.

Glymour MM, Hamad R. Causal thinking as a critical tool for eliminating social inequalities in health. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(5):623.

Kondo N, Sembajwe G, Kawachi I, van Dam RM, Subramanian SV, Yamagata Z. Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: meta-analysis of multilevel studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4471.

Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:316–26.

Schwartz S. The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: the potential misuse of a concept and the consequences. Am J Public Health (1971). 1994;84(5):819–24.

Preston SH. The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Popul Stud. 1975;29(2):231–48.

Wilkinson RG. Income distribution and life expectancy. Br Med J. 1992;304(6820):165–8.

Tennant PWG, Murray EJ, Arnold KF, Berrie L, Fox MP, Gadd SC, et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;50:620–32.

Pazzagli L, Linder M, Zhang M, Vago E, Stang P, Myers D, et al. Methods for time-varying exposure related problems in pharmacoepidemiology: an overview. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(2):148–60.

Deaton A. Income, health, and well-being around the world: evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(2):53–72.

Jen MH, Jones K, Johnston R. Global variations in health: evaluating Wilkinson’s income inequality hypothesis using the World Values Survey. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(4):643–53.

van Deurzen I, van Oorschot W, van Ingen E. The link between inequality and population health in low and middle income countries: policy myth or social reality? PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115109.

Barro RJ. Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. J Econ Growth. 2000;5(1):5–32.

Kuznets S. Economic growth and income inequality. Am Econ Rev. 1955;45(1):1–28.

Das M, Das SK, World Scientific (Firm). Economic growth, income inequality, and poverty. Economic growth and income disparity in BRIC: Theory and empirical evidence. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; 2014.

Deaton A. Health, inequality, and economic development. J Econ Lit. 2003;41(1):113–58.

Shin I. Income inequality and economic growth. Econ Mod. 2012;29(5):2049–57.

Hirsch D, Padley M, Stone J, Valadez-Martinez L. The low income gap: a new indicator based on a minimum income standard. Soc Indicators Res. 2020;149(1):67–85.

Gravelle H. How much of the relation between population mortality and unequal distribution of income is a statistical artefact? BMJ. 1998;316(7128):382–5.

Truesdale BC, Jencks C. The health effects of income inequality: averages and disparities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37(1):413–30.

Blakely TA, Woodward AJ. Ecological effects in multi-level studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(5):367–74.

Andreas B, Therese N, Daniel W. The ecological fallacy: what conclusions can be drawn from group averages? Sick of inequality? An introduction to the relationship between inequality and health. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2016.

Gravelle H, Wildman J, Sutton M. Income, income inequality and health: what can we learn from aggregate data? Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(4):577–89.

Macleod J, Davey Smith G, Metcalfe C, Hart C. Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):1916–29.

Wilkinson RG, Pickett K. The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin Books; 2010.

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The enemy between us: the psychological and social costs of inequality. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2017;47(1):11–24.

Kragten N, Rözer J. The income inequality hypothesis revisited: assessing the hypothesis using four methodological approaches. Soc Indicators Res. 2017;131(3):1015–33.

Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1233–6.

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Socioeconomic determinants of health: health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ. 1997;314(7086):1037.

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and socioeconomic gradients in mortality. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):699–704.

Judge K. Income distribution and life expectancy: a critical appraisal. BMJ. 1995;311(7015):1282–7.

Mellor JM, Milyo J. Reexamining the evidence of an ecological association between income inequality and health. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26(3):487–522.

Nettle D. Why inequality is bad. Hanging on to the edges. Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life. 1st ed. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers; 2018. p. 111–28.

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1768–84.

Lochner K, Pamuk E, Makuc D, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State-level income inequality and individual mortality risk: a prospective, multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):385–91.

Osler M, Prescott E, Gr⊘nbæk M, Christensen U, Due P, Engholm G. Income inequality, individual income, and mortality in Danish adults: analysis of pooled data from two cohort studies. BMJ. 2002;324(7328):13.

Kahn RS, Wise PH, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: cross sectional national survey. BMJ. 2000;321(7272):1311–5.

Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Income inequality and health: what does the literature tell us? Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21(1):543–67.

Blakely TA, Kennedy BP, Glass R, Kawachi I. What is the lag time between income inequality and health status? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(4):318–9.

Jutz R. The role of income inequality and social policies on income-related health inequalities in Europe. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):117.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Shimonovich M, Pearce A, Thomson H, Keyes K, Katikireddi SV. Assessing causality in epidemiology: revisiting Bradford Hill to incorporate developments in causal thinking. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;36:873–87.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1311–6.

VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–74.

Andreas B, Therese N, Daniel W. Measuring inequality sick of inequality? An introduction to the relationship between inequality and health. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2016.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37.

Ganna A, Ingelsson E. 5 year mortality predictors in 498,103 UK Biobank participants: a prospective population-based study. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):533–40.

Bombak AE. Self-rated health and public health: a critical perspective. Front. Public Health. 2013;1:15.

Mateen FJ, Oh J, Tergas AI, Bhayani NH, Kamdar BB. Titles versus titles and abstracts for initial screening of articles for systematic reviews. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:89–95.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Res (Southampton, England). 2013;1(1):1–320.

Jeyaraman MM, Rabbani R, Copstein L, Robson RC, Al-Yousif N, Pollock M, et al. Methodologically rigorous risk of bias tools for nonrandomized studies had low reliability and high evaluator burden. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;128:140–7.

Igelström E, Campbell M, Craig P, Katikireddi SV. Cochrane’s risk of bias tool for non-randomized studies (ROBINS-I) is frequently misapplied: a methodological systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;140:22–32.

Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(8):758–64.

Schünemann HH, Higgins JP, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Skoetz N, et al. Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]. Cochrane. 6; 2019. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-14.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):407–15.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence—indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1303–10.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D, et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1283–93.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1294–302.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1277–82.

Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, Mustafa RA, Meerpohl JJ, Thayer K, et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:105–14.

Acknowledgements

Valerie Wells supported the search strategy development.

Funding

GM is a salaried employee of the NHS. MS, AP, HT, and SVK are supported by the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU17) and the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/2). AP is supported by the Wellcome Trust (GB) (205412/Z/16/Z). SVK is supported by NRS Senior Clinical Fellowship (SCAF/15/02). MS is supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_ST_U18004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS conceptualized the methods and drafted the manuscript. The review team developed the protocol, including articulating the research focus and methods, in meetings and discussions. SVK, AP, HT, and GM reviewed several drafts of the manuscript and provided feedback on content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Search strategy for MEDLINE and EMBASE (conducted January 2021)

-

1.

Socioeconomic Factors/

-

2.

Income/

-

3.

(individual adj1 income).ab,ti.

-

4.

(income inequality or income inequity).ab,ti.

-

5.

(gini adj (index or ratio or coefficient)).ab,ti.

-

6.

health disparities.ab,ti.

-

7.

Mortality/

-

8.

“Cause of Death”/

-

9.

Life Expectancy/

-

10.

life expectancy.ab,ti.

-

11.

Health/

-

12.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6

-

13.

7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

-

14.

12 and 13

-

15.

limit 14 to yr=”1992 - 2020

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimonovich, M., Pearce, A., Thomson, H. et al. Assessing the causal relationship between income inequality and mortality and self-rated health: protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 11, 20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01892-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01892-w