Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a significant public health problem affecting a large proportion of the population and is associated with adverse health consequences and a substantial economic burden. Despite the existence of effective treatment, undiagnosed OSA remains a challenge. The gold standard diagnostic tool is polysomnography (PSG), yet the test is expensive, labour intensive and time-consuming. Home-based, limited channel sleep study testing (levels 3 and 4) can advance and widen access to diagnostic services. This systematic review aims to summarise available evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of limited channel tests compared to laboratory and home PSG in diagnosing OSA.

Methods

Eligible studies will be identified using a comprehensive strategy across the following databases from inception onwards: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, SCOPUS, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Emcare and Web of Science Core Collection and ProQuest databases. The search will include a full economic evaluation (i.e. cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, cost-benefit, cost-consequences and cost-minimisation analysis) that assesses limited channel tests and PSG. Two reviewers will screen, extract data for included studies and critically appraise the articles for bias and quality. Meta-analyses will be conducted if aggregation of outcomes can be performed. Qualitative synthesis using a dominance ranking matrix will be performed for heterogeneous data.

Discussion

This systematic review protocol uses a rigorous, reproducible and transparent methodology and eligibility criteria to provide the current evidence relating to the clinical and economic impact of limited channel and full PSG OSA diagnostic tests. Evidence will be examined using standardised tools specific for economic evaluation studies.

Trial registration

PROSPERO (CRD42020150130)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a condition characterised by airflow cessation or obstruction caused by complete or partial collapse of the upper airway, which affects 9 to 38% of the general adult population [1, 2]. Unfortunately, underdiagnosed OSA is common, occurring in 75 to 90% of individuals in the US general adult population and adult surgical patients [3,4,5]. In Australia, studies have reported up to 10% of individuals remain undiagnosed and untreated in the community [6, 7]. When left untreated, individuals with OSA are at heightened risks of metabolic syndrome [8,9,10,11], cardiovascular diseases [12,13,14], neurocognitive abnormalities [15, 16], mental health problems [17], behavioural alteration [18], traffic collisions [19], workplace accidents and productivity losses [20,21,22], reduced quality of life [23, 24] and premature death [25,26,27,28]. The high prevalence and various adverse health outcomes associated with OSA contribute to significant economic costs [29,30,31]. In Australia, OSA accounts for $408.5 million of total health system costs and $2.6 billion of indirect financial costs, making it the highest contributor to sleep disorder-related expenses [32].

The health and economic burden related to OSA can be diminished with effective and efficient case-identification and treatment. The latter is readily available and found to be cost-effective [33,34,35]. A recent systematic review that investigated the impact of OSA therapies suggested that treating OSA has a positive effect on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and can reduce health care utilisation and costs [36]. Despite the existence of effective treatments, case identification of OSA remains a challenge and creates the need to widen diagnostic access for those with suspected OSA [37]. The current gold standard for diagnosing OSA is full overnight laboratory polysomnography (PSG, i.e. level I study)) [38,39,40]. However, laboratory PSG is expensive, time-consuming and labour intensive, which creates further access barriers to OSA diagnosis [38,39,40]. Researchers have investigated alternatives to laboratory PSG, which include portable PSG (i.e. level 2 [L2] study) and limited channel testing (i.e. level 3 [L3] and level 4 [L4] studies) that are typically performed in the patient’s home. While full PSG typically (L1 and L2 studies) utilises more than seven recording channels, L3 (polygraphy) measures four to seven channels, while L4 uses only one to three physiological measures to derive a diagnosis [41], making them less labour intensive and less time consuming to report. Previous studies have demonstrated favourable results showing a high level of agreement between limited-channel testing and in-laboratory PSG, particularly when diagnosing moderate to severe OSA [42, 43].

Limited channel tests can advance and widen access to diagnostic services and treatment initiation in OSA, ultimately reducing the substantial economic burden related to OSA. However, to date, research into their cost-effectiveness remains limited and contentious. Scarce evidence exists for the cost-effectiveness of L4 devices despite results suggesting that a single-channel sensor offers a cheaper alternative to polysomnography [44]. Previous economic evaluation models assessing the economic impact of polygraphy (i.e. L3 testing) relative to PSG using published data showed contradictory results [45,46,47]. However, several empirical studies found consistent results signifying similar effectiveness and lower costs of L3 studies vs. PSG [48,49,50,51,52,53]. Despite the longstanding controversy of the value and efficiency of polygraphy, the test was approved by the US Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine practice parameters for use in selective populations in 2008 [54, 55]. Following the change in the health insurance policy that enables reimbursement for home sleep polygraphy in the USA, there has been a growing demand for limited-channel testing for OSA [56]. However, L3 tests are still not compensated by the Medicare Benefits Schedule in Australia where access to OSA diagnosis remains restricted [57].

Robust evidence about the potential economic benefit of OSA diagnostic testing is required to guide decision-makers towards better allocation of scarce healthcare resources. Only a few studies have sought to investigate the health economic impact of OSA diagnostic studies [58, 59]. One previous literature review included nine studies, predominantly examining the cost of diagnostic testing [58]. In contrast, the most recent review has focused on constructing a cost-effectiveness model of OSA management based on existing data [59]. However, none have thoroughly examined the evidence related to the cost and effectiveness of limited channel testing compared to PSG. Hence, we aim to address this gap in the literature by conducting a structured systematic review of economic studies to capture, critically appraise and synthesise data related to health economic outcomes of OSA diagnostic tests, focusing on L3, L4 and PSG testings (LI and L2) in adult OSA populations. Our review will generate information that will help decision-makers determine whether implementing limited channel testing provides value for money for OSA case identification.

Methods

This protocol has been registered with the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42020150130) and is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [60] (see checklist in Additional file 1).

Inclusion criteria

Population

This review will include studies of individuals aged 18 years or older. There is no maximum limit of age.

Intervention of interest and comparator

The intervention of concern includes limited channel tests (L3 and L4 studies), while the comparator will be attended and unattended PSG (L1 and L2 studies). The limited channel tests utilise lesser channels that are typically part of the PSG. L3 assessment uses at least four channels, including measure of airflow, heart rate, respiratory movement and oximetry [61]. L4 usually employs single or two-channel system, including oximetry [61]. However, for the purpose of this review, any limited channels system that does not meet the minimum benchmark for L3 study will be categorised as L4.

Setting

Although limited channel systems are mainly designed to be conducted unattended in the patient’s home, they can also be used for attended studies in the laboratory. As the review is focused on the use of limited channel tests, there will be no restriction as to where the sleep study took place. Studies that compared full PSG and limited-channels tests either in a laboratory or at a patient’s home, unattended or attended will be considered for inclusion.

Study design

The systematic review will consider both model and non-model based full economic evaluation studies (i.e. cost-minimisation analysis [CMA], cost-effectiveness analysis [CEA], cost-benefit analysis [CBA], cost-consequence analysis [CCA] and cost-utility analysis [CUA]) that investigate limited channel studies versus polysomnography.

Costs and outcome measures

Expenses related to the interventions, resource use, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of OSA will be reported in the review. In terms of cost-effectiveness measures, the units will vary according to the study design. The findings for CEA and CCA studies will generally be expressed in terms of cost per unit of effect in clinical outcome with those for CUA expressed as QALY and disability-adjusted life years for CUA [62]. The net benefit ratio will be reported for CBA studies [62]. The outcome measurements for the CEA, CCA and CUA can be summarised in the form of an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, that is generated by dividing the difference in costs by the outcome relative to the study [62]. The probability of the cost-effectiveness of targeted intervention at a different monetary threshold, typically derived from the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, will be reported in the case where insufficient reporting of studies were found. This review will include all cost perspectives as reported by identified studies including societal, patient and third-party payers (e.g. government, health insurance, employer).

Language

The review will include studies published in English.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that include children, adolescents (< 18 years old) and non-human subjects will be excluded. Exclusion criteria will also extend to theory papers, letters, conference proceedings, theses, dissertations, reviews, editorials and studies where full texts could not be attained.

Information sources and search strategy

Several steps will be undertaken to find economic evaluation studies on OSA diagnostic testing. First, we will conduct a preliminary search through MEDLINE, focusing on the titles, abstract and index terms to develop key terms for three key pre-defined concepts relating to the research question.

The first concept is related to sleep apnoea and sleep breathing disorders. The second term is related to OSA diagnostic testing, which includes polysomnography, polygraphy, limited channels, home sleep apnoea test, portable monitoring and home sleep test. While economic evaluation, QALY, quality of life, cost analysis, CMA, CCA, CUA, CEA, CBA, healthcare costs and economic model built the third search concept.

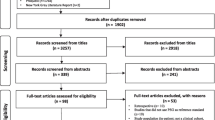

Following the identification of keywords and index terms, we will conduct a full search using the developed search strategy connected by the ‘AND’ operator across the following databases from inception onwards: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Emcare, Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, CINAHL, Web of Science Core Collection and ProQuest databases (see Additional file 2). A minimum of one key concept must be present in the search result. Eligible studies will be selected through screening of the title, abstract and full-text appraisal by at least two reviewers. Cross-reference checking of relevant identified articles will be undertaken as the final step of the search strategy. EndNote X9 (©2020 Clarivate Analytics) and Covidence (©2017 Covidence) will be used to manage data throughout the initial search, quality assessment and data extraction.

Study selection

At least two independent reviewers will select studies based on the eligibility criteria. If conflict or disagreement arises between the reviewers, a research team discussion will be conducted to resolve issues until a consensus is reached.

Data extraction and synthesis

The reviewers will extract data from included papers using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Data Extraction Form for Economic Evaluations [63]. Descriptive data extracted will be comprised of information on the study population and setting, intervention and comparator, economic evaluation methods, analytic perspective(s), source of effectiveness data, prices and currency, analytical duration, cost-effectiveness method, sensitivity analysis, measures of resource use, cost and health outcome(s). Furthermore, study findings on healthcare utilisation effectiveness, cost and cost-effectiveness measures will also be reported. The authors will then discuss factors that promote or reduce the cost-effectiveness of OSA diagnostic testing according to the comparative results of the included economic studies.

Data extracted from relevant papers will first be analysed and summarised qualitatively using the JBI Dominance Ranking Matrix [63], which displays three-by-three matrix with three classifications of economic studies: strong dominance, weak dominance and non-dominance. Subgroups analysis will be undertaken in terms of different sleep study types and comparators (e.g. L1 vs. L3, L2 vs L4), as well as the severity of OSA (e.g. mild, moderate, severe) where relevant.

If the nature of data extraction allows for aggregation of results in terms of quality, quantity and contexts of the identified studies, where possible economic findings (i.e. differences in cost and ICER between intervention and control groups) in relevant subgroups will be synthesised using meta-analysis in Stata 16 [64]. Clinical outcomes that can be expressed as binary outcomes will be reported as odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval (CI), whilst continuous data such as cost and ICER will be reported as mean differences (MD) along with its 95% CI. The OR and MD estimates will be calculated using an appropriate technique (e.g. the Mantel-Haenszel method [65] for categorical binary outcomes and random or fixed-effect models [66] for continuous data). The I2 statistic will be used to measure heterogeneity, with a value of 85% or higher indicating significant heterogeneity [67]. Financial costs reported in the study will be presented in 2020 Australian Dollars (AUD) with originally published costs in parentheses. Results originally published from non-AUD currencies will be converted to AUD for the publication year using purchasing power parity and then adjusted for inflation using a health-related inflation index where relevant.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

Methodological quality and validity checks of the included economic evaluation studies will be conducted by two reviewers primarily using JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Economic Evaluation [68], a quality assessment tool based on the guidelines developed by Drummond et al. [62]. An additional checklist by Philips et al. [69] will be utilised specifically for economic studies using a modelling study design or hypothetical cohort. Since economic evaluation studies often employ various cost perspectives and report distinctive health economic measures in different contexts and regions, the European Network of Health Economic Evaluation Databases checklist will be used to further assess generalisability and transferability of included studies [70].

Discussion

The proposed systematic review will be reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [71]. This systematic review will present current evidence relating to the economic impact of OSA diagnostic testing methods (i.e. limited channel versus full sleep study testing) using a reproducible and transparent systematic literature search. We have outlined comprehensive inclusion and exclusion criteria of eligible studies, which encompass study design, context, target population, intervention and comparator, cost and outcomes measures. A search strategy and a list of databases for searching have been determined, followed by a strategy for data extraction and synthesis. Included studies will be subjected to critical appraisal using standardised tools tailored for model and non-model based economic evaluation studies. Some potential limitations of this review include the heterogeneity of findings and cost perspective, which can influence the aggregability, transferability and generalisability of extracted data. Another limitation is information bias originating from our restriction to studies reported in English language and adult populations. However, this review is timely in addressing and identifying gaps in current evidence regarding diagnostic options for OSA. Our findings can potentially inform evidence-based decision making when implementing limited channel sleep study testing, particularly in Australia, where undiagnosed OSA and constrained access to diagnostic services remains an important issue.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AUD:

-

Australian Dollar

- CBA:

-

Cost-benefit analysis

- CCA:

-

Cost-consequence analysis

- CEA:

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMA:

-

Cost minimisation analysis

- CUA:

-

Cost-utility analysis

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- L1:

-

Level one (attended polysomnography)

- L2:

-

Level two (unattended polysomnography)

- L3:

-

Level three (polygraphy)

- L4:

-

Level four (single to three-channel OSA diagnostic test)

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnoea

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement

- PSG:

-

Polysomnography

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life years

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;328(17):1230–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199304293281704.

Chamara VS, Jennifer LP, Caroline JL, Adrian JL, Brittany EC, Melanie CM, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. 2017.

Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20(9):705–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/20.9.705.

Finkel KJ, Searleman AC, Tymkew H, Tanaka CY, Saager L, Safer-Zadeh E, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic medical center. Sleep Medicine. 2009;10(7):753–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.007.

Kapur V, Strohl KP, Redline S, Iber C, O'Connor G, Nieto J. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in US communities. Sleep and Breathing. 2002;6(02):049–54. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32318.

Appleton SL, Gill TK, Lang CJ, Taylor AW, McEvoy RD, Stocks NP, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of sleep conditions in Australian adults: 2016 Sleep Health Foundation national survey. Sleep health. 2018;4(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.10.006.

Simpson L, Hillman DR, Cooper MN, Ward KL, Hunter M, Cullen S, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea in the general population and methods for screening for representative controls. Sleep and Breathing. 2013;17(3):967–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-012-0785-0.

Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, Resnick HE. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The sleep heart health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh261.

Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;172(12):1590–5. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200504-637OC.

Hirotsu C, Haba-Rubio J, Togeiro SM, Marques-Vidal P, Drager LF, Vollenweider P, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea as a risk factor for incident metabolic syndrome: a joined Episono and HypnoLaus prospective cohorts study. European Respiratory Journal. 2018;52(5):1801150. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01150-2018.

Reutrakul S, Mokhlesi B. Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetes: a state of the art review. Chest. 2017;152(5):1070–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.009.

Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, Gottlieb DJ, Nawabit R, Kirchner HL, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The sleep heart health study. American J Respiratory Critical Care Med. 2006;173(8):910–6. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC.

Konecny T, Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Orban M, Pressman GS, Kara T, Gami A, et al. Under-diagnosis of sleep apnea in patients after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(9):742–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.032.

Drager LF, McEvoy RD, Barbe F, Lorenzi-Filho G, Redline S. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: Lessons from recent trials and need for team science. Circulation. 2017;136(19):1840–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029400.

Davies CR, Harrington JJ. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on neurocognitive function and impact of continuous positive air pressure. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(3):287–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.04.006.

Bucks RS, Olaithe M, Eastwood P. Neurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnoea: A meta-review. Respirology. 2013;18(1):61–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02255.x.

Lang CJ, Appleton SL, Vakulin A, McEvoy RD, Vincent AD, Wittert GA, et al. Associations of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea and excessive daytime sleepiness with depression: an Australian population study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(04):575–82. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6546.

Tufik S, Andersen ML, Bittencourt LRA, de Mello MT. Paradoxical sleep deprivation: Neurochemical, hormonal and behavioral alterations. Evidence from 30 years of research. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 2009;81(3):521–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0001-37652009000300016.

Vennelle M, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Sleepiness and sleep-related accidents in commercial bus drivers. Sleep and Breathing. 2010;14(1):39–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-009-0277-z.

Guglielmi O, Jurado-Gámez B, Gude F, Buela-Casal G. Job stress, burnout, and job satisfaction in sleep apnea patients. Sleep Medicine. 2014;15(9):1025–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.015.

Jurado-Gámez B, Guglielmi O, Gude F, Buela-Casal G. Workplace accidents, absenteeism and productivity in patients with sleep apnea. Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition). 2015;51(5):213–8.

Omachi TA, Claman DM, Blanc PD, Eisner MD. Obstructive sleep apnea: a risk factor for work disability. Sleep. 2009;32(6):791–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.6.791.

Finn L, Young T, Palta M, Fryback DG. Sleep-disordered breathing and self-reported general health status in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 1998;21(7):701–6.

Baldwin CM, Griffith KA, Nieto FJ, O'Connor GT, Walsleben JA, Redline S. The Association of Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Sleep Symptoms with Quality of Life in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2001;24(1):96–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/24.1.96.

Knauert M, Naik S, Gillespie MB, Kryger M. Clinical consequences and economic costs of untreated obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2015;1(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wjorl.2015.08.001.

Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(19):2034–41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043104.

Punjabi NM, Caffo BS, Goodwin JL, Gottlieb DJ, Newman AB, O'Connor GT, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLOS Medicine. 2009;6(8):e1000132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132.

Marshall NS, Wong KKH, Cullen SRJ, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea and 20-year follow-up for all-cause mortality, stroke, and cancer incidence and mortality in the Busselton health study cohort. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(4):355–62. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3600.

Rejón-Parrilla JC, Garau M, Sussex J. Obstructive sleep apnoea health economics report. [Internet] London: Office of Health Economics; 2014. p. 1–39. [cited 2021 April 4]. Available from: https://snorer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/OHE-OSA-health-economics-report---FINAL---v2.pdf.

Leger D, Bayon V, Laaban JP, Philip P. Impact of sleep apnea on economics. Sleep medicine reviews. 2012;16(5):455–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.10.001.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. Underdiagnosing and undertreating obstructive sleep apnea draining healthcare system Mountain View. CA: Frost & Sullivan; 2016.

Deloitte Access Economics. Re-awakening Australia: The economic cost of sleep disorders in Australia, 2010, Report for the Sleep Health Foundation Australia. 2011.

Guest JF, Panca M, Sladkevicius E, Taheri S, Stradling J. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure to manage obstructive sleep apnea in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Diab Care. 2014;37(5):1263–71.

Jennum P, Kjellberg J. Health, social and economical consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: a controlled national study. Thorax. 2011;66(7):560–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.143958.

Quinnell TG, Bennett M, Jordan J, Clutterbuck-James AL, Davies MG, Smith IE, et al. A crossover randomised controlled trial of oral mandibular advancement devices for obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea (TOMADO). Thorax. 2014;69(10):938–45. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205464.

Wickwire EM, Albrecht JS, Towe MM, Abariga SA, Diaz-Abad M, Shipper AG, et al. The impact of treatments for OSA on monetized health economic outcomes: a systematic review. Chest. 2019;155(5):947–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.01.009.

Freedman N. COUNTERPOINT: does laboratory polysomnography yield better outcomes than home sleep testing? No. Chest. 2015;148(2):308–10. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-0479.

Hossain JL, Shapiro CM. The prevalence, cost implications, and management of sleep disorders: an overview. Sleep Breathing. 2002;6(02):085–102. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32322.

Flemons WW, Douglas NJ, Kuna ST, Rodenstein DO, Wheatley J. Access to diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected sleep apnea. Am J Respir Critical Care Med. 2004;169(6):668–72. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200308-1124PP.

Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(03):263–76.

Collop N. Home sleep apnea testing for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, post TW (Ed) edn UpToDate; 2017.

El Shayeb M, Topfer L-A, Stafinski T, Pawluk L, Menon D. Diagnostic accuracy of level 3 portable sleep tests versus level 1 polysomnography for sleep-disordered breathing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cmaj. 2014;186(1):E25–51. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.130952.

Abrahamyan L, Sahakyan Y, Chung S, Pechlivanoglou P, Bielecki J, Carcone SM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of level IV portable sleep monitors versus polysomnography for obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep and Breathing. 2018;22(3):593–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-017-1615-1.

Masa JF, Duran-Cantolla J, Capote F, Cabello M, Abad J, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Effectiveness of home single-channel nasal pressure for sleep apnea diagnosis. Sleep. 2014;37(12):1953–61. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4248.

Chervin RD, Murman DL, Malow BA, Totten V. Cost-utility of three approaches to the diagnosis of sleep apnea: polysomnography, home testing, and empirical therapy. Ann Internal Med. 1999;130(6):496–505. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00006.

Reuveni H, Schweitzer E, Tarasiuk A. A cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative at-home or in-laboratory technologies for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Medical decision making. 2001;21(6):451–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X0102100603.

Deutsch PA, Simmons MS, Wallace JM. Cost-effectiveness of split-night polysomnography and home studies in the evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(02):145–53. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.26508.

Parra O, Garcia-Esclasans N, Montserrat J, Eroles LG, Ruiz J, López J, et al. Should patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome be diagnosed and managed on the basis of home sleep studies? Euro Respir J. 1997;10(8):1720–4. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.97.10081720.

Álvarez MLA, Santos JT, Guevara JC, Martínez MG, Pascual LR, Bañuelos JLV, et al. Reliability of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. analysis of costs. Archivos de Bronconeumología ((English Edition. 2008;44(1):22–8.

White DP, Gibb TJ, Wall JM, Westbrook PR. Assessment of accuracy and analysis time of a novel device to monitor sleep and breathing in the home. Sleep. 1995;18(2):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/18.2.115.

Whittle A, Finch S, Mortimore I, MacKay T, Douglas N. Use of home sleep studies for diagnosis of the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 1997;52(12):1068–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.52.12.1068.

Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga M-Á, Carmona-Bernal C, Sánchez-Armengol Á, de la Torre AS, Durán-Cantolla J, et al. Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Critical Care Med. 2017;196(9):1181–90. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201612-2497OC.

Hui DS, Ng SS, To K-W, Ko FW, Ngai J, Chan KK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an ambulatory approach versus the hospital-based approach in managing suspected obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Scientific Rep. 2017;7(1):45901. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45901.

Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, Claman D, Goldberg R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):737–47.

Collop NA, Tracy SL, Kapur V, Mehra R, Kuhlmann D, Fleishman SA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea devices for out-of-center (OOC) testing: technology evaluation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(05):531–48. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.1328.

Quan SF, Epstein LJ. A warning shot across the bow: the changing face of sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(04):301–2. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.2570.

Hamilton GS, Chai-Coetzer CL. Update on the assessment and investigation of adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Australian J Gen Pract. 2019;48(4):176–81. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-12-18-4777.

He K, Kim R, Kapur VK. Home-vs. Laboratory-based management of OSA: an economic review. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2016;2(2):107–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-016-0042-3.

Toraldo D, Passali D, Sanna A, De Nuccio F, Conte L, De Benedetto M. Cost-effectiveness strategies in OSAS management: a short review. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2017;37(6):447–53. https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-1520.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Littner MR. Portable monitoring in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Seminars Respir Critical Care Med. 2005;26(1):56–67. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-864200.

Drummond MF, Sculphe MJ, Torrance GW, O'brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programs. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 edition / Supplement. Adelaide, South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2019. https://www.stata.com/support/faqs/resources/citing-software-documentation-faqs/.

Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Nat Cancer Institute. 1959;22(4):719–48.

Cooper H. Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach: Sage publications; 2015.

Leonarde-Bee J. Presenting and interpreting meta-analyses: Heterogenity School of Nursing and Academic Division of Midwifery. Nottingham: University of Nottingham; 2007.

Gomersall JS, YT YTJ, Xue Y, Lockwood S, Riddle D, Preda A. Conducting systematic reviews of economic evaluations. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):170–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000063.

Philips Z, Ginnelly L, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Golder S, Riemsma R, et al. Review of guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2004;8(36) iii-iv, ix-xi:1–158.

Nixon J, Rice S, Drummond M, Boulenger S, Ulmann P, de Pouvourville G. Guidelines for completing the EURONHEED transferability information checklists. Eur J Health Economics. 2009;10(2):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-008-0115-4.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Acknowledgements

We thank Flinders University for enabling us to access articles that are not freely available. Special thanks to Ms. Shannon Brown who helped with the database search strategy. We also acknowledge the authors of primary studies.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from the Australian Government Research Training Program and National Health and Medical Research Council: Clinical Research Excellence, National Centre of Sleep Health Services Research (Grant ID 1134954).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception was by ANN and BK. Design and writing of the first draft of the manuscript were by ANN. ANN, BK, AV and CLC contributed to the development of the selection criteria and search strategy. AV, RJA, RDM and CLC provided expertise on sleep apnoea. BK advised regarding health economic approach. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategy draft for main electronic database.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Natsky, A.N., Vakulin, A., Coetzer, C.L.C. et al. Economic evaluation of diagnostic sleep studies for obstructive sleep apnoea: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10, 104 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01651-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01651-3