Abstract

Background

Length of stay (LOS) for inpatient psychiatric services is an important factor with serious drawbacks when it is extended more than needed. Impacts on economy, social functioning, and stigma can hamper improvement and affect the patients’ experiences on future mental healthcare. Predictions of which patients have a higher chance for prolonged LOS have been extensively researched. Previous systematic reviews found consistent predictors of both longer and shorter LOS. However, they do not provide an estimate from the pooled effect sizes. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no meta-analysis on the influence of these factors. The primary objective of this study will be to provide point estimates on the effect sizes of all studied predictors of the LOS of psychiatric inpatients.

Methods

We will conduct a systematic search in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO for observational studies evaluating the effect size of independent factors on the length of stay of psychiatric inpatients. Prospective and retrospective cohorts that assess the influence of predictors through the reporting of standardized regression coefficients will be included. We will provide a qualitative synthesis of the findings from each study and perform a meta-analysis from pooled regression coefficients that were adjusted for other variables or confounders in order to obtain a point estimate and confidence interval for all factors extracted from the included studies.

Discussion

The results from this study may provide more accurate predictions for mental health institutions, psychiatrists, mental health service providers, patients, and families on the prognosis regarding the length of stay for needed inpatient care. This information may be used to anticipate individuals with a higher chance for prolonged hospitalization to plan the necessary interventions for these specific situations. Considering both the benefits and disadvantages of longer and shorter stays, the pooled estimates for independent factors may be used by mental healthcare providers and patients for informed decision-making. The results from this study will also update results presented in previous studies and identify the strengths and limitations from the current available evidence.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO ID CRD42020172840

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Hospitalization remains a vital intervention for patients with severe mental disorders [1]. In spite of its benefits, the experience of staying in a psychiatric hospital frequently is associated with low satisfaction [2], which may influence the patients’ attitude towards further mental healthcare [3]. One of the core determinants of this experience is the length of stay (LOS), defined as the number of days between discharge and admission.

Trends of the LOS for psychiatric inpatient care vary according to the geographic region. A recent prospective cohort of high-income European nations reported that the average LOS for hospitalized psychiatric patients was 39.4 days, ranging from 17.9 mean days in Italy to 55.1 mean days in Belgium [4]. In the USA, the maximum reported mean LOS in a systematic review of 30 studies was 24.9 days [5], 2 weeks shorter compared to other high-income countries in Europe. Comparatively, a prospective study of 385 psychiatric inpatients in Brazil reported a median LOS of 25 days [6]. A cross-sectional study in Nepal determined that the average LOS was 19.4 days, 20 days less compared to the mean in Europe [7]. While in most countries the duration of the hospital stay is less than 40 days, there is a clear variability between low-, middle-, and high-income nations, in accordance with the availability of resources.

The effects of the LOS on multiple outcomes in psychiatric inpatients have been extensively studied. As more studies continue to contribute to the large body of evidence, it has become clearer that longer stays are usually associated with more negative outcomes. These include deterring social and community-related skills [8], increased suicidal ideation related to stigma [9], social functioning [10], post-traumatic stress [11], and productivity and finances [12]. Although an ideal LOS remains uncertain, current international recommendations advocate for an early discharge as soon as stabilization is successful, in order to continue their management in a less restrictive environment [13]. On the contrary, concerns on prioritizing shorter admissions include an increase in medical negligence and favoring a “revolving-door” pattern. A Cochrane review from 2014 concluded that patient outcomes and rates of readmissions were similar between short and long LOS, albeit the quality of the evidence was low to very low [14]. This does suggest, however, that planning shorter admissions does not increase readmissions or the risk of discharging patients without addressing all urgent symptoms or issues. Despite these efforts, the LOS is still greater compared to other non-psychiatric hospitalization [15].

Given the influence of the LOS on public health, patient outcomes, and finances, a growing volume of studies have aimed to evaluate factors predicting if an individual has a higher chance for longer hospitalization time. Qualitative synthesis of the available literature was first attempted by Tulloch et al. In their systematic review of 30 studies that analyzed predictors with the LOS of general psychiatric inpatients, several factors were associated with longer LOS including psychosis, female gender, and larger hospital size. On the contrary, voluntary discharge, prospective payment, married status, younger age, and detained status were associated with shorter LOS [5]. Studies were only from the USA, and meta-analysis was not attempted. Another more recent systematic review by Gopalakrishna et al. reported similar findings, with the addition of involuntary admission, mood disorders, use of restraints, and poor treatment response associated with longer LOS [16]. Both studies have contributed towards the anticipation of patients with a higher risk for institutionalization, but do not provide an estimate of the size of the effect on their studied variables on the LOS. While both may be associated with short or long LOS, their comparative magnitude remains uncertain. These are provided by both of the mentioned studies but, to the best of our knowledge, there are no meta-analyses evaluating this adjusted effect of predictors. The importance of the LOS lies not only on the clinical outcome of inpatients, but also on the economic, social, and emotional consequences.

Research question

In psychiatric inpatients of a mental health institution or hospital, what are the independent predictors of their length of stay?

What is the size of the effect of these independent predictors on the length of stay?

Objective

The objectives of this systematic review and meta-analysis include:

-

1.

To summarize all factors which influence the length of stay in psychiatric inpatients.

-

2.

To update previous similar studies with more recent published literature.

-

3.

To pool standardized effect sizes to provide an overall point estimate and confidence interval of factors associated with a longer or shorter length of stay.

Methods

Protocol registration

The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020172840) on April 28, 2020 (see Additional file 1) and to an independent Research Committee. This study will adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17] and the checklist with the reported items is provided as an additional file (see Additional file 2).

Study selection criteria

To be included, studies must fulfill the following criteria:

-

1.

Study design: Prospective or retrospective observational studies.

-

2.

Population characteristics: Inpatients of a psychiatric department/hospital/facility with an Axis I disorder defined by the International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10), or Axis I or II disorder as defined by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition (DSM-IV), 4th Edition Text-Revised (IV-TR) or 5th Edition (DSM-5).

-

3.

Intervention: Modifiable and non-modifiable factors/determinants/predictors of length of stay (sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, diagnosis, disorder, and treatment-related characteristics).

-

4.

Outcome: Primary outcome is the length of stay in the psychiatric hospital/institution or facility. Only studies which calculated the effect size through reporting of β-coefficients will be included.

There will be no language restrictions for the studies included. Cross-sectional and prospective or retrospective observational studies which do not fulfill all the above criteria for population, intervention, and outcome will be excluded. Duplicate studies assessing the same population which do not report additional data will also be excluded. To reduce the risk of bias by confounders, we will only consider studies reporting the outcomes of interest through adjusted standardized regression coefficients in this meta-analysis.

Search process

An independent and experienced librarian (NAAV) will carry out a systematic search in PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO to find eligible articles between inception and July 2020. The complete search strategy is provided in an additional file (see Additional file 3). The keywords used were generated through Web of Science and Scopus Controlled vocabulary.

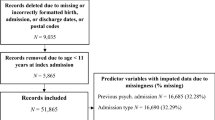

Six reviewers working independently and in duplicate will screen all abstracts and select full-text manuscripts for eligibility. Prior to formal abstract screening, a pilot phase between reviewers will be carried out to clarify misunderstandings and ensure comprehension. Chance-adjusted inter-rater agreement for the title/abstract screening and the full-text eligibility will be calculated using Fleiss’ Kappa, considering a value > 0.7 as indicative of good inter-rater reliability [18]. After title and abstract screening, a second phase of full-text eligibility assessment will ensue. Disagreements at this stage will be resolved by consensus, and reasons for exclusion will be documented by the reviewers. If no consensus is reached, decision will be based on the arbitration of a third reviewer. Abstract screening and full-text selection will be completed using DistillerSR [19], a web-based software designed for screening and data extraction.

Data extraction

A standardized web-based data extraction form will be designed for the extraction of the information of interest from each study. Data collection will be performed independently and in duplicate by the research team. Discrepancy between reviewers regarding the extracted information will be resolved by consensus or intervention of a third reviewer. From each eligible study the following data will be extracted onto the standardized form:

-

Study characteristics: Year, country, design, length, type of mental health institution/hospital level, sample size.

-

Sociodemographic variables: Age, sex, education, ethnicity, marital status, type of insurance, accommodation, occupation, income status.

-

Medical History: Medical or psychiatric disorders in first- or second-degree family members, psychiatric hospitalization history in first- or second-degree family members, previous and number of psychiatric hospitalizations, previous and number of suicide attempts, time from last psychiatric hospitalization, weight, BMI, medical comorbidities.

-

Disorder-related: Primary diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time elapsed since diagnosis, severity rated by clinimetry at admission, voluntary or involuntary admission.

-

Treatment: Pharmacotherapy, dosage, duration, non-pharmacological therapy.

-

Length of stay: Standardized regression coefficients, total variance, confidence interval, standard errors, mean days of length of stay.

Studies which present compounded terms involving more than one of the aforementioned (i.e., diagnosis plus pharmacotherapy, and age plus diagnosis) will not be considered for the data extraction or the statistical analysis. Furthermore, only standardized regression coefficients that have been adjusted for multiple predictors will be obtained from the included studies. If outcomes or data related to predictions were stated to be assessed in the study but were not reported thereafter either in the results or discussion, we will contact the corresponding author twice through e-mail. If the corresponding author does not respond, we will attempt to contact other authors.

Statistical analysis

We will provide a qualitative synthesis of the included studies involving their design, country, type of mental health hospital or institution, population characteristics, predictors studied, and a summary of the main findings that includes the average, median or interquartile length for the LOS. For the meta-analysis, we will pool the standardized adjusted regression coefficients (β), sample sizes, and standard error as a measure of the effect size of predictors relative to length of stay [20, 21]. Studies that only report the unadjusted coefficients will be included for the systematic review but not for the quantitative analysis, in order to reduce bias. If 95% confidence intervals, standard deviations, or the interquartile range are provided instead of the standard error, we will estimate it with the data provided [22]. A priori selected predictors for meta-analysis are presented in Additional file 4. Nonetheless, in order to reduce the possibilities of increased false-positive rates, meta-analysis will only be performed for predictors with at least ten studies reporting the standardized regression coefficients [23]. Details concerning further steps to test for this are presented in the following sections. With the pooled results we will generate point estimates with 95% confidence intervals on the relationship between each individual predictor and the LOS. We will consider a two-tailed value of p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Heterogeneity of the predictors subjected to meta-analysis that have met the described criteria will be assessed through the I2 statistic. A value of I2 > 50% will be taken as indicative of high heterogeneity not explained by chance [24]. Based on the heterogeneity, the results will be presented using a fixed or random-effects model. When low (< 50%), we will perform the statistical analysis using a fixed-effects model. When the heterogeneity is high (> 50%), we will perform the statistical analysis using a random-effects model and conduct thereafter sensitivity analyses to address underlying causes for the significant heterogeneity. This analysis method has been described to reduce the rates of type I error [23]. Specific sensitivity analyses are presented in the next section. All calculations will be performed using the R meta-package [25, 26].

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (FCN and ESU) of the research team will address the risk of bias in each individual study. Since studies considered for inclusion have an observational nature, we will use the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Scale (NOS) for evaluating prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Domains that will be evaluated include selection quality (representativeness, ascertainment of exposure), comparability quality, and outcome quality (assessment of the outcome, follow-up). Studies will be rated and deemed of good, fair, or poor quality according to the conversion thresholds from the NOS to the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) [27]. Disagreements on risk of bias between reviewers will be resolved by consensus or by the arbitration of a third reviewer (AFGM).

Publication bias

To assess for publication bias, we will use funnel plots of the effect size compared to the standard error [28]. In the presence of plot asymmetry for a given analysis, we will use the trim-and-fill method to determine the impact of removing smaller studies on the overall estimate and provide adjusted results [29].

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

If an appropriate number of studies from diverse countries/continents are found, a subgroup analysis by country, continent, and its income status will be carried out to evaluate if differences observed from the general pooled data are significant in specific countries with lower or higher economic status. We also have pre-planned to perform separate analyses for studies involving only a specific diagnosis (i.e., psychotic disorders and substance abuse) In these cases, meta-analyses of correlation will be performed only for studies of that specific disorder. Other a priori sensitivity analyses will be reported based on the quality of the included studies and meta-bias. For the former, only studies rated as good quality will be included for a subgroup analysis to test for differences with the primary pooled estimate (which includes studies with fair or poor quality). If we obtain point estimates from the quality sensitivity analysis that differ significantly from the overall pooled analysis, we will consider the former with more credibility. Furthermore, if other a priori subgroup or sensitivity analyses report significantly different results in comparison to the overall pooled analysis we will consider the overall quality of the different groups to evaluate the validity of the findings.

Permutation test

The robustness of the pooled standardized regression coefficients will be tested through permutation tests, which has been a recommended method for recalculation of p values and statistical significance [23, 30].

Discussion

From preliminary searches, we have identified there is a substantial body of evidence that should provide sufficient data in order to generate confident estimates. Our study will only consider for inclusion results reported as adjusted standardized regression coefficients. This will limit our analysis in part as other studies evaluating the outcomes of interest with different statistical methods (i.e., hazard, risk, or odds ratio) will be excluded. The robustness of the estimates could also be negatively influenced by the quality of the included studies, given their observational nature. Although this will be addressed in sensitivity/subgroup analyses explained above, there may be a significantly low number of studies of good quality that would make extrapolation of these conclusions not possible. Finally, the discussion from this study will address the following points involved in the informed-decision process:

-

Provide more accurate predictions for mental health institutions, psychiatrists, mental health service providers, patients, and families on the prognosis regarding the length of stay for needed inpatient care.

-

Identify patients with a higher probability for prolonged hospitalization in order to plan the necessary interventions for these specific situations.

-

Highlight the strengths and limitations from the current available evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All additional files are available.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- MINI:

-

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- SCID:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition

- DSM-VI-TR:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition Text-Revised

- DSM-V:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Health Research and Quality

References

Wang DWL, Colucci E. Should compulsory admission to hospital be part of suicide prevention strategies? BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(3):169–71.

Bird V, Miglietta E, Giacco D, Bauer M, Greenberg L, Lorant V, et al. Factors associated with satisfaction of inpatient psychiatric care: A cross country comparison. Psychol Med. 2019;50(2):284–92.

Błądziński P, Hat M, Daren A, Kruk D, Depukat A, Cichocki Ł, et al. Subjective Evaluation Of Admission And First Days Of Hospitalization At A Psychiatric Ward From The Perspective Of Patients I Pierwszych Dni Hospitalizacji Na Oddziale Psychiatrycznym Z Perspektywy Pacjentów. Adv Psychiatry Neurol. 2020;29(1):39–53.

Dimitri G, Giacco D, Bauer M, Jane V, Greenberg L, Lasalvia A, et al. Predictors of length of stay in psychiatric inpatient units : Does their effect vary across countries ? Eur Psychiatry. 2018;48:6–12. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.001.

Tulloch AD, Fearon P, David AS. Length of stay of general psychiatric inpatients in the United States: Systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(3):155–68.

Baeza FLC, Da Rocha NS, Fleck MP. Predictors of length of stay in an acute psychiatric inpatient facility in a general hospital: A prospective study. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2018;40(1):89–96.

Basnet M, Sapkota N, Limbu S, Baral D. Length of stay of psychiatric admissions in a tertiary care hospital. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2018;56(210):593–7.

Newman L, Harris V, Evans LJ, Beck A. Factors Associated with Length of Stay in Psychiatric Inpatient Services in London, UK. Psychiatr Q. 2018;89(1):33–43.

Xu Z, Müller M, Lay B, Oexle N, Drack T, Bleiker M, et al. Involuntary hospitalization, stigma stress and suicidality: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(3):309–12.

Tseng MCM, Chang CH, Liao SC, Yeh YC. Length of stay in relation to the risk of inpatient and post-discharge suicides: A national health insurance claim data study. J Affect Disord. 2020;266(21):528–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.014.

Guzmán-Parra J, Aguilera-Serrano C, García-Sanchez JA, García-Spínola E, Torres-Campos D, Villagrán JM, et al. Experience coercion, post-traumatic stress, and satisfaction with treatment associated with different coercive measures during psychiatric hospitalization. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(2):448–56.

Davlasheridze M, Goetz SJ, Han Y. The Review of Regional Studies The Effect of Mental Health on U.S. County Economic Growth *. Off J South Reg Sci Assoc. 2018;48:155–71 Available from: www.srsa.org/rrs.

Sharfstein SS. Goals of Inpatient Treatment for Psychiatric Disorders. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60(1):393–403.

Babalola O, Gormez V, Na A, Johnstone P, Sampson S. Length of hospitalisation for people with severe mental illness (Review); 2014.

Saba DK, (Thomson Reuters), Levit KR, (Thomson Reuters), Elixhauser A. (AHRQ). Hospital Stays Related to Mental Health, 2006. HCUP Statistical Brief #62. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb62.pdf.

Gopalakrishna G, Ithman M, Malwitz K. Predictors of length of stay in a psychiatric hospital. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19(4):239–45.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):1000097. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

McGinn T, Wyer PC, Newman TB, Keitz S, Leipzig R, Guyatt G. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic). Cmaj. 2004;171(11):1369–73.

Evidence Partners. DistillerSR. Ottawa: Evidence Partners; 2016. Available from: https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/

Peterson R, Brown S. On the Use of Beta Coefficients in Meta-Analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(1):175–81.

Bowman NA. Effect Sizes and Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis in Higher Education. Res High Educ. 2012;53(3):375–82.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ WV. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane. 2019. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med. 2004;23(11):1663–82.

Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2000.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. Available from: http://www.r-project.org/

Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Mental Health. 2019;22:153–60.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2012. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Shi L, Lin L, Omboni S. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: Practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicien. 2019;98(23):e15987. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6571372/#:~:text=The%20idea%20of%20the%20trim%2Dand%2Dfill%20method%20is%20to,based%20on%20the%20bias%2Dcorrected.

Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Ebert DD. Meta-Regression. In: Doing Meta-Analysis in R: A Hands-on Guide; 2019. Available from: https://bookdown.org/MathiasHarrer/Doing_Meta_Analysis_in_R/.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the research associates of the Plataforma INVEST-UANL Ker Unit Mexico for guidance regarding methodological aspects of this protocol.

Funding

The proposed work has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FCN contributed to the conception, registration, design, drafting, and revision of the proposed study. NSTR contributed to the drafting and revision of the proposed study. AFGM has also contributed to the drafting and revision of the proposed study. NAAV has contributed to the registration, design, and proposed statistical analysis. AMCM has contributed to the drafting and reviewing of the proposed study. ESU contributed to the conception, design, drafting, and revision of the proposed study. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to its submission. All authors agree to be personally accountable for the contributions declared.

Authors’ information

FCN is a medical physician and research assistant at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital “Dr. José E. González”.

NSTR is a psychologist and master’s student at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital “Dr. José E. González”.

AFGM is a medical physician and collaborator at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital “Dr. José E. González”.

NAAV is a family medicine specialist, statistician, and professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (UANL) and the Ker Unit Mexico.

AMCM is a medical student at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon.

ESU is the guarantor of this protocol, a psychiatrist, medical doctor, and research director at the Advanced Neuroscience Center Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital “Dr. José E. González”. He is also a professor of medicine at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval or consent is required for the proposed study.

Consent for publication

The authors provide consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

PROSPERO.

Additional file 2:

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist.

Additional file 3:

Search Strategy.

Additional file 4:

Pre-specified Predictors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Carranza Navarro, F., Álvarez Villalobos, N.A., Contreras Muñoz, A.M. et al. Predictors of the length of stay of psychiatric inpatients: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 10, 65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01616-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01616-6