Abstract

Background

Chronic musculoskeletal pain represents an enormous burden in society. Best-practice care for chronic musculoskeletal pain suggests adoption of self-management strategies. Telehealth interventions (e.g., videoconferencing) are a promising approach to promote self-management and have the potential to overcome geographical barriers between patient and care providers. Understanding patient perspectives will inform and identify practical challenges towards applying the self-management strategies delivered via telehealth to everyday lives. The aim of this study is to synthesize the perceptions of individuals with musculoskeletal pain with regards to enablers and barriers to engaging in telehealth interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain self-management.

Methods

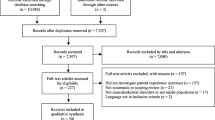

A systematic review of qualitative studies will be performed based on searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, LILACS, and PsycINFO databases. Screening of identified titles will be conducted by two independent investigators. Data extraction will retrieve detailed qualitative information from selected articles. The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist will be used for critical appraisal of included studies, and the level of confidence in the findings will be assessed using the confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual). A thematic synthesis approach will be used to derive analytical themes.

Discussion

This review will systematically identify, synthesize, and present enablers and barriers reported by people with musculoskeletal pain to engage in telehealth interventions. The review will provide information required to support the design and improvement of telehealth services.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019136148

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The International Association of Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as an unpleasant experience that may or may not be linked to actual tissue damage [1]. Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting longer than the expected time for tissue recovery (around 3 months) [2]. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, such as osteoarthritis, back and neck pain, are the leading causes of years lived with disability across the world according to the Global Burden of Disease Study (2016) [3, 4]. In both high- and low-income countries these conditions have shown increased prevalence over the past two decades, illustrating the challenges of their management [4, 5]. Barriers reported by clinicians (e.g., consultation time, resources) and patients (e.g., service availability, geographical location) in translating evidence-based recommendations into practice contribute to the growing burden of musculoskeletal pain [6,7,8].

Best practice recommends self-management strategies (including education and exercise) for optimizing the management of musculoskeletal pain [8, 9]. Engaging with this type of treatment demands an active participation from the patient towards a lifestyle change, knowledge, and involves shared decision-making processes with clinicians [8, 10]. Telehealth is a promising mode of delivery for self-management strategies [7, 11]. Telehealth includes the use of technologies and related services (e.g., telephone, virtual reality, videoconference, apps, websites) to allow interactions (synchronous/real-time, e.g., videoconference, and/or asynchronous/store-forward, e.g., digital images) between healthcare providers and patients [12]. Telehealth interventions bring important value to health care programs as they overcome geographical barriers between patients and clinicians [13].

The evidence for telehealth interventions in improving musculoskeletal pain-related outcomes is favorable, and the results are comparable to face-to-face interventions [7, 14]. A recent systematic review of 13 randomized controlled trials found that telehealth interventions are as effective as usual/face-to-face care interventions for improving pain and function in people with musculoskeletal conditions [15]. O’Brien et al. [7] reported a small positive effect on pain and disability after reviewing the effectiveness of telehealth interventions compared to usual/face-to-face care for musculoskeletal pain. Healthcare providers believe online resources as a useful adjunct to face-to-face delivered treatments for chronic pain [16, 17]. Patients also have favorable attitudes to telehealth approaches of healthcare delivery. Feeling of “closeness at a distance,” independence, and improved knowledge about their “body and self” was perceived by patients who participated in a telehealth program after shoulder joint replacement [18]. Previous studies also found good patient satisfaction rates in telehealth interventions based on cognitive behavioral therapy and exercise and pain-coping intervention [19, 20].

Despite the promise of telehealth interventions, the implementation of technology within health systems as an alternative means for delivering care remains a challenge [6]. Patient and public engagement are a major issue for the expansion of telehealth [21]. Difficulties guaranteeing good internet access to remote areas, or access to adequate devices [22], as well as lack of acceptance from the elderly population [18], and poor interaction with web-based sources of information [23], have been identified as barriers to uptake of telehealth interventions. Low educational level and low income were also associated with inadequate internet access and use [24].

To maximize the access to, uptake and use of telehealth interventions in musculoskeletal pain management, it is important to understand patient perspectives towards engaging with these types of healthcare delivery. Understanding patient perspectives will inform and identify practical challenges towards implementing telehealth strategies in the future. There has been no comprehensive review of available evidence regarding patients’ perception towards telehealth. This systematic review aims to synthesize the perceptions of individuals with musculoskeletal pain with regards to enablers and barriers to engaging in telehealth interventions for chronic pain self-management.

Methods

The review protocol was registered at the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews. The protocol was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist [25].

Search strategy

Electronic databases will include MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, LILACS, and PsycINFO. Forward and backward citation searches of included articles and relevant systematic reviews will also be conducted. There will be no language and search period restriction. Detailed search strategy is presented in Appendix.

Eligibility criteria

Individuals presenting with any previously diagnosed or self-reported chronic musculoskeletal pain condition (e.g., back pain, neck pain, osteoarthritis), including post-surgical procedures due to a primary musculoskeletal condition. The definition of chronic pain will be aligned with ICD-11 classification [2] and will focus on conditions related to the musculoskeletal system, including diagnoses that can be subsumed under a different category (e.g., chronic widespread pain), aiming to include a wide range of studies and conditions. Inclusion criteria following the SPIDER format is available in Table 1 [26].

Studies that seek to guide telehealth intervention development by exploring patients’ opinions regarding what interventions should involve will be excluded. Mixed methods and qualitative studies primarily using quantitative data analysis approaches will be excluded.

Intervention/exposure

Telehealth interventions will be defined as any intervention provided at a distance using telecommunication networks as a medium to deliver rehabilitation care [12]. We will not distinguish between telehealth, telemedicine, telerehabilitation, telecare, or other similar terms. In this review telehealth will broadly include professional and patient interaction (online and offline) and delivery of pain management intervention at a distance (e.g., home exercises, pain education, self-management strategies, telephone counseling). It could comprise any combination of the following: one to one or group videoconferences, access to websites or apps, mobile and/or telephone. Studies that also present face-to-face or use written/paper-based material in combination with telehealth interventions will be included only when they report qualitative data specific to the telehealth component.

Types of studies to be included

Qualitative studies (e.g., focus groups or individual interviews) and analysis methods (e.g., thematic analysis or phenomenological analysis) focused on exploring perceptions/experiences or attitudes of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Studies may include people who have engaged entirely or partially in telehealth interventions, e.g., people who started a telehealth intervention program and completed it; people who started a telehealth intervention and interrupted it. Mixed-method studies with a qualitative component will be included; only the qualitative data will be used for this review.

Data extraction (selection and coding)

Two investigators will perform the title and abstract screening, and disagreements will be resolved by consensus or by a third investigator. The full text of eligible records will be retrieved and assessed by two investigators. Disagreement between the reviewers regarding the full text will be resolved initially by discussion and, if necessary, arbitration by a third reviewer. In case of insufficient or unclear information in a potentially eligible article, the authors will be contacted by email and a timeframe of 3 weeks to reply will be considered before article exclusion. Data extraction will be conducted by reviewers with previous experience in systematic reviews and qualitative research methodology.

We will extract the following data from included articles: author, year, country, design, data collection method, participant characteristics, type and description of the intervention, and qualitative information (themes/sub-themes) regarding enablers and barriers disclosed in results, discussion (if applicable), or annex/appendix sections.

Critical appraisal of included studies

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) guidelines will be used to appraise the methodological quality of the included studies (Table 2) [27]. Two investigators will assess the quality of the studies individually. Discrepancies between will be resolved by discussion. A third investigator will be consulted for arbitration if necessary.

Strategy for data synthesis

We will use a 3-step thematic synthesis method for data synthesis guided by an inductive approach [28]. The results section of the primary studies (verbatim) will be imported to NVivo or Microsoft Excel sheet. First, line-by-line coding of the results and discussion (if applicable) of the included articles will be performed. The discussion section will be coded only to provide additional contextual information if required. Subsequently, “descriptive themes” will be created based on the analysis of the results of the included studies. The last stage will involve generating “analytical themes” by studying each category and merging them in case of similarities, leading to the creation of major themes relevant to the key aim of this meta-synthesis [28]. Once the coding is complete, the research team will discuss the synthesis of findings and examine the derived major themes, aiming for consensus regarding the final themes.

The level of confidence for main findings from the meta-synthesis will be assessed using the confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) approach [29]. This method aims to assess the extent to which confidence can be placed in findings from qualitative synthesis. GRADE-CERQual approach is based on an assessment of the individual findings in terms of 4 components:

- 1)

Methodological limitations of included studies—the extent to which there are concerns regarding the design of the primary studies that contributed to a review finding [30].

- 2)

Coherence of review findings—assessment of how clear, well supported, and compelling is the communication between data from primary studies and a review finding addressing those data [31].

- 3)

Adequacy of data contributing to a review finding—determination on how rich is the data supporting a review finding [32].

- 4)

Relevance of included studies to the review question—to what extent the evidence from the primary studies support the review findings and its application to the context specified in the review question (focusing on perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) [33].

This assessment will lead to judgment of the level of confidence in the evidence supporting each individual review finding [34]. The grading system is described as follows:

High confidence. It is highly likely that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Moderate confidence. It is likely that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Low confidence. It is possible that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Very low confidence. It is not clear whether the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Each one of the 4 components will be categorized as follows: “no or very minor concerns,” “minor concerns,” “moderate concerns,” or “serious concerns”. All findings will start as high confidence and will be downgraded by one level if presenting “minor” and “moderate concerns;” evidence presenting “serious concerns” will be downgraded by two levels.

Discussion

Achieving patient engagement in telehealth interventions is essential for positive outcomes but can be extremely challenging due to various barriers (e.g., cultural, social, economic). Despite existing evidence identifying telehealth interventions as a promising means of improving health dissemination to underserved populations, little is known about how best to deliver care to patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain remotely or using web-based sources. A qualitative evidence synthesis approach is best suited to address this research question. Systematic review of qualitative evidence allows an in-depth understanding of gaps from the point of view of the end users for whom the treatment is designed.

Using qualitative evidence synthesis brings relevant information on people’s perceptions, experiences, and opinions regarding interventions, health care services, policies, and processes [29]. When complemented by evidence related to effectiveness and costs, this information is better suited to informing decision-making and policy development, leading to improvements in implementation, practice, and health [29, 35].

This review will systematically identify, synthesize, and report the most common enablers and barriers for people with musculoskeletal pain to engage in telehealth interventions. The review will provide clear information required for designing and improving health services based on telehealth interventions and technology development.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

References

International Association for the Study of Pain - IASP. IASP terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698.

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156(6):1003–7.

DALYs GBD, Collaborators H. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1260–344.

Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Marinho F, de Azeredo Passos VM, Carvalho Malta D, Barboza França E, Abreu DMX, Araújo VEM, et al. Burden of disease in Brazil, 1990–2016: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2018;392(10149):760–75.

Sundararaman LV, Edwards RR, Ross EL, Jamison RN. Integration of mobile health technology in the treatment of chronic pain: a critical review. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2017;42(4):488–98.

O'Brien KM, Hodder RK, Wiggers J, Williams A, Campbell E, Wolfenden L, et al. Effectiveness of telephone-based interventions for managing osteoarthritis and spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5846.

Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Goucke R, Nagree Y, Gibberd M, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. British journal of sports medicine. 2019:bjsports-2018-099878.

Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–83.

Hutting N, Johnston V, Staal JB, Heerkens YF. Promoting the use of self-management strategies for people with persistent musculoskeletal disorders: the role of physical therapists. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2019;49(4):212–5.

Martorella G, Boitor M, Berube M, Fredericks S, Le May S, Gelinas C. Tailored web-based interventions for pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2017;19(11):e385.

Fisk M, Rudel D, R R. Definitions of terms in telehealth 2011. 28-46 p.

Guilkey RE, Draucker CB, Wu J, Yu Z, Kroenke K. Acceptability of a telecare intervention for persistent musculoskeletal pain. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2018;24(1):44–50.

Pastora-Bernal JM, Martin-Valero R, Baron-Lopez FJ, Estebanez-Perez MJ. Evidence of benefit of telerehabitation after orthopedic surgery: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2017;19(4):e142.

Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O’Leary SP, Hill AJ, Russell TG. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2017;31(5):625–38.

Hinman RS, Nelligan RK, Bennell KL, Delany C. “Sounds a bit crazy, but it was almost more personal:” a qualitative study of patient and clinician experiences of physical therapist-prescribed exercise for knee osteoarthritis via Skype. Arthritis care & research. 2017;69(12):1834–44.

Devan H, Godfrey H, Perry M, Hempel D, Saipe B, Hale L, et al. <p>Current practices of health care providers in recommending online resources for chronic pain self-management</p>. Journal of Pain Research. 2019;12:2457–72.

Eriksson L, Lindstrom B, Ekenberg L. Patients’ experiences of telerehabilitation at home after shoulder joint replacement. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2011;17(1):25–30.

Dear BF, Gandy M, Karin E, Ricciardi T, Fogliati VJ, McDonald S, et al. The pain course: a randomised controlled trial comparing a remote-delivered chronic pain management program when provided in online and workbook formats. Pain. 2017;158(7):1289–301.

Bennell KL, Nelligan R, Dobson F, Rini C, Keefe F, Kasza J, et al. Effectiveness of an internet-delivered exercise and pain-coping skills training intervention for persons with chronic knee pain: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;166(7):453–62.

O’Connor S, Hanlon P, O’Donnell CA, Garcia S, Glanville J, Mair FS. Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2016;16(1):120.

DeMonte CM, DeMonte WD, Thorn BE. Future implications of eHealth interventions for chronic pain management in underserved populations. Pain management. 2015;5(3):207–14.

Chu JT, Wang MP, Shen C, Viswanath K, Lam TH, Chan SSC. How, when and why people seek health information online: qualitative study in Hong Kong. Interactive journal of medical research. 2017;6(2):e24.

Manganello J, Gerstner G, Pergolino K, Graham Y, Falisi A, Strogatz D. The relationship of health literacy with use of digital technology for health information: implications for public health practice. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP. 2017;23(4):380–7.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. Implementing PRISMA-P: recommendations for prospective authors. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):15.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative health research. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme - CASP Qualitative Checklist 2018. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation science : IS. 2018;13(Suppl 1):2.

Munthe-Kaas H, Bohren MA, Glenton C, Lewin S, Noyes J, Tuncalp O, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 3: how to assess methodological limitations. Implementation science : IS. 2018;13(Suppl 1):9.

Colvin CJ, Garside R, Wainwright M, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Bohren MA, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 4: how to assess coherence. Implementation science : IS. 2018;13(Suppl 1):13.

Glenton C, Carlsen B, Lewin S, Munthe-Kaas H, Colvin CJ, Tunçalp Ö, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 5: how to assess adequacy of data. Implementation Science. 2018;13(S1).

Noyes J, Booth A, Lewin S, Carlsen B, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 6: how to assess relevance of the data. Implementation science : IS. 2018;13(Suppl 1):4.

Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative findings table. Implementation science: IS. 2018;13(Suppl 1):10.

Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006;3:CD004563.

Acknowledgements

Dr Saragiotto reports grants from the Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP/ grant number 2016/24217-7) and Ms. Fernandes holds a master scholarship from Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP/ process number 2019/14032-8).

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF and BS were responsible for the main writing and subsequent development of the manuscript; HD, SK, and CW revised the entire manuscript, focusing on methodological adjustments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

MEDLINE electronic search strategy

1 pain.mp.

2 “chronic pain”.mp. or exp Chronic Pain/

3 “persistent pain”.mp.

4 1 or 2 or 3

5 qualitative.mp. or exp Qualitative Research/

6 “focus group”.mp. or exp Focus Groups/

7 “grounded theory”.mp. or exp Grounded Theory/

8 phenomenology.mp.

9 “mixed method”.mp.

10 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

11 “self management”.mp. or exp Self Care/

12 pain management.mp. or exp Pain Management/

13 telemedicine.mp. or exp Telemedicine

14 tele health.tw. or tele*health.tw.

15 tele care.tw. or tele*care.tw.

16 e*health.tw. or ehealth.tw.

17 home*based.tw.

18 mobile health.tw. or mhealth.tw. or m health.tw. or m*health.tw.

19 telephone.tw. or exp Telephone/

20 smart phone.tw. or smart*phone.tw. or mobile phone.tw.

21 apps.tw.

22 exp Mobile Applications/

23 text messaging.tw. or exp Text Messaging/

24 exp Internet/ or Internet.tw.

25 internet*based.tw.

26 online.tw.

27 web based.tw. or webbased.tw.

28 computer based.tw.

29 videoconferencing.tw. or exp Videoconferencing/

30 tablet device.tw.

31 iPad.tw.

32 iPhone.tw.

33 distance.tw.

34 remotely delivered.tw.

35 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34

36 4 and 10 and 35

Limit humans

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandes, L.G., Devan, H., Kamper, S.J. et al. Enablers and barriers of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain for engaging in telehealth interventions: protocol for a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Syst Rev 9, 122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01390-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01390-x