Abstract

Background

Gasless laparoscopy, developed in the early 1990s, was a means to minimize the clinical and financial challenges of pneumoperitoneum and general anaesthesia. It has been used in a variety of procedures such as in general surgery and gynecology procedures including diagnostic laparoscopy. There has been increasing evidence of the utility of gasless laparoscopy in resource limited settings where diagnostic imaging is not available. In addition, it may help save costs for hospitals. The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the available evidence surrounding the safety and efficiency of gasless laparoscopy compared to conventional laparoscopy and open techniques and to analyze the benefits that gasless laparoscopy has for low resource setting hospitals.

Methods

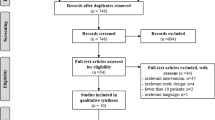

This protocol is developed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis–Protocols (PRISMA-P). The PRISMA statement guidelines and flowchart will be used to conduct the study itself. MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Central, and Global Index Medicus (WHO) will be searched and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials database. The articles that will be found will be pooled into Covidence article manager software where all the records will be screened for eligibility and duplicates removed. A data extraction spreadsheet will be developed based on variables of interest set a priori. Reviewers will then screen all included studies based on the eligibility criteria. The GRADE tool will be used to assess the quality of the studies and the risk of bias in all the studies will be assessed using the Cochrane Risk assessment tool. The RoB II tool will assed the risk of bias in randomized control studies and the ROBINS I will be used for the non-randomized studies.

Discussion

This study will be a comprehensive review on all published articles found using this search strategy on the safety and efficiency of the use of gasless laparoscopy. The systematic review outcomes will include safety and efficiency of gasless laparoscopy compared to the use of conventional laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Trial registration

The study has been registered in PROSPERO under registration number: CRD42017078338

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately 5 billion people around the world do not have access to safe, timely, and affordable surgical and anesthestic care [1]. Abdominal surgical conditions comprise a burden of disease that cannot be calculated, according to the World Bank’s DCP-3, due to a lack of data [2]. However, the Lancet report on global burden of disease 2013 estimates the global mortality rate per 100,000 for appendicitis is 0.7, gallbladder, and liver conditions is 1.6 and intestinal obstruction is 3.9 [3]. In addition, in India, a study showed that there are 1.1% of deaths (0–69 years) from acute abdominal condition corresponding around 72,000 deaths nationally in 2020 [4]. In high-income settings, many patients requiring abdominal surgery will undergo minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, prudently preceded by diagnostic imaging. Conventional laparoscopy has a variety of benefits over open laparotomy [5] and can reduce pain [6], reduce wound infection [7], promote faster post-operative recovery [8], and return to quality of life [9].

In resource-limited healthcare settings in low-middle income countries, many patients who require abdominal surgery undergo open laparotomy or go without surgery altogether. Anecdotally, many abdominal conditions remain undiagnosed due to lack of access to diagnostic imaging and diagnostic procedures (i.e., endoscopy, laparoscopy). These resource deficiencies lead to avoidable morbidity and mortality which could be reduced with access to laparoscopic surgery. However, for resource-limited hospitals, conventional laparoscopy is oftentimes unaffordable. Air-tight trochars are expensive, carbon dioxide gas cannot often easily be acquired, and general anaesthesia which is required for patients undergoing pneumoperitoneum, is often impossible without anaesthesiologists and ventilator equipment.

Gasless laparoscopy was developed in the early 1990s [10] to overcome clinical and financial challenges of pneumoperitoneum and general anesthesia. The technique involves a form of mechanical elevation of the anterior abdominal wall. Through either a single incision or multiple ports, a variety of gynaecological [11,12,13,14], upper gastrointestinal [15,16,17], lower gastrointestinal [18,19,20,21], and exploratory diagnostic [22, 23] procedures can be performed. Many trials have been conducted investigating the safety outcomes (peri and post-operative complication rate) [21, 24,25,26] and efficiency outcomes [14, 27] when compared with the mainstay treatment methods.

There are a variety of tested benefits for implementing gasless laparoscopy technique. It may carry significantly reduced costs when compared with conventional laparoscopy, including significantly cheaper equipment costs [21, 26,27,28] maintenance costs, and anesthesia requirements [21]. Gasless laparoscopy may also have an equal or shorter duration of inpatient stay compared with laparotomy or conventional laparoscopy [11, 22, 28]. Additionally, gasless technique avoids the hemodynamic burden with abdominal insufflation [19, 29, 30], and therefore can be used under spinal anesthesia in patients with hemodynamic compromise (e.g., in exploratory, laparoscopy for abdominal trauma).

For resource-limited hospitals where diagnostic imaging is unavailable, gasless laparoscopy is a financially affordable diagnostic option. Other unstudied benefits may include improved safety outcomes in pregnancy [31], reduced rates of post-site metastases [32], and reduced contamination in contaminated procedures [33]. A common documented risk involved in gasless laparoscopy includes poor visualization [11, 15, 33]; however, this has only been documented anecdotally and has not yet been associated with a clinically significant difference when compared to conventional laparoscopy.

When considering the applicability of gasless laparoscopy to resource-limited settings, a variety of information remains unknown in the literature. While a number of different gasless technology designs have been trialled [14, 19, 34, 35], it is not clear which gasless technology design could be standardized for use in a variety of settings for a variety of procedures. It is also unclear whether trials have been conducted which risk-adjust the complication rates according to patient’s acuity and comorbidities prior to gasless laparoscopy or use compound complication outcomes, and few trials seem to have been performed using randomization [11, 21, 28, 36].

Additionally, it is not clear whether any trials describe the training process for surgeons prior to the trial such as the training that was required to achieve the safety and efficiency outcomes. This is an important factor in implementing a new technique into a rural resource-limited setting which will include the time-investment required for surgeons to learn to use gasless laparoscopy safely and efficiently. To this date, there are no studies for gasless laparoscopy describing the surgical learning curve (i.e., volume of cases required), the ease of adoption into hospitals, and the surgeon and patient satisfaction with their experience with gasless laparoscopy.

This systematic review aims to determine the safety and efficiency of gasless laparoscopy when compared to with alternative treatment methods for surgery.

Methods/design

Study design

This systematic review protocol is developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocol guidelines (PRISMA-P) [37]. The PRISMA statement guidelines including the flowchart will be followed to track all records pulled from all the database search. The study has been registered in the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42017078338.

Search strategy

The study will include an automated and manual search of articles using the databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Web of Science and Cochrane Central, Global Index Medicus from the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institutes of Health clinical trials database. Studies published from 1992 and later will be included which is when gasless laparoscopy was first introduced. The selected articles will then undergo further selection using Boolean terms such as AND/OR. The final included articles will be pooled and managed using Covidence software reference and article manager software. All duplicated will then be identified by the software and removed electronically and manually. The following search terms are used: (((gasless OR non insufflative OR noninsufflative OR non pneumoperiton* OR nonpneumoperiton*).ab,ti OR (abdom* adj3 lift*).ab,ti OR (abdominal wall adj3 (suspension OR elevat*)).ti,ab) AND (laparos* OR laparot* OR peritoneoscop* OR minimally invasive surgery).ab,ti) OR (laparolift OR abdolift).ab,ti. Table 1 shows the search terms used in MEDLINE.

Study selection

The articles that will be included will follow the PICO tool (Table 2). The population of interest includes human adults of 18 years or more and not restricted to a certain race or geographic location and will include procedures performed at any hospital level. The intervention of interest includes trials involving gasless laparoscopy training, technology or technique, any trial involving general surgical procedures or conditions, or any trial involving diagnostic laparoscopy performed for general surgical investigation, and; any variation of gasless technology and device design, and; any variation of gasless technique, and; any variation of a gasless training program or any mention of background training prior to trial. The comparison group includes patients who have either received no intervention, or; have undergone a general surgical procedure using conventional laparoscopy, or; open laparotomy. The outcomes of interest are the safety and efficiency of gasless laparoscopy. The study will also include case-control, cohort, and randomized control trial and non-randomized control trial studies. In addition, studies published in English or Swedish will be included on or after 1992 (Table 3) and other languages will be excluded, but tracked to understand how many were excluded based on language.

Data extraction and analysis

The review process will include two independent reviewers and then a meeting will be conducted to ensure an overall consensus has been met on all included studies. Should non-agreement on any study arise among the three reviewers, the senior author expertise will be sought to advice on the remaining studies. Screening of studies will start with title and abstract, followed by full-text screening following the inclusion criteria of studies identified a priori. A data extraction spreadsheet will be developed on Microsoft Excel based on variables identified by the research team. The risk of bias across all studies will be assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool where the RoB II will be used to assess bias in randomized control trials [38]. The ROBINS-I tool will be used to assess the risk of bias in non-randomized studies [39]. Figures and tables will offer a graphical presentation of the strength of included studies and cumulative risk of bias across all studies. The data will then be analyzed based on the outcomes and subcategories will be identified. The GRADE tool will also be used to help in the full assessment of the quality and risk of bias of the included studies.

Data synthesis

A qualitative synthesis will be provided for the strength of evidence for each outcome of interest, particularly focusing on difference in harm outcomes between control and intervention groups. This comment will be on the general direction of the effect, and not the effect size, and will focus on results derived from article with low or moderate risk of bias. For each outcome, we will comment on possible precision and strength of association, weakness of existing evidence, sources of systematic bias (limitations, directness, consistency), and overall risk of biases (selection, confounding, performance, attrition, detection and reporting).

A qualitative synthesis will be provided around the strengths and limitations of the included studies, the heterogeneity of existing literature, the generalizability of the synthesized results to other populations, alternative interventions, a variety of settings, and different patient outcomes. Since qualitative synthesis will be sought in this study, the synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guidelines will also be used in conjunction with PRISMA [40]. Additionally, alternate explanations for existing evidence will be considered, and potential for future development may also be discussed. A limitation that could potential arise is the lack of homogeneity of the studies included. This will prompt avoiding meta-analysis of the studies and a qualitative synthesis of the results and description will be used.

Discussion

The safety of gasless laparoscopy will be reflected through three categories. The first is the number of complications identified from the procedure. Complications might include but are not restricted to pain, hemorrhage, visceral perforation, infection (wound/deep tissue), medical events (pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, stroke), and biomedical or metabolic effects. The second category includes readmission that can be for a conversion to a laparotomy. The third category is the all-cause mortality from the procedure.

Efficiency of gasless laparoscopy will then be assessed using three categories: the procedural set-up time, the duration of the procedure, and the average length of stay. The results will be discussed in relation to findings of the published literature.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis – Protocols

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Aug 8 [cited 2018 Feb 27];386(9993):569–624. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014067361560160X.

Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN. Essential Surgery: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition. Washingt Int Bank Reconstr Dev / World Bank; Apr. 2015;1.

Moraga P, GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017 Sep 16;390(10100):1151–210.

Dare AJ, Ng-Kamstra JS, Patra J, Fu SH, Rodriguez PS, Hsiao M, Jotkar RM, Thakur JS, Sheth J, Jha P, Million Death Study Collaborators. Deaths from acute abdominal conditions and geographical access to surgical care in India: a nationally representative spatial analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2015 Oct 1;3(10):e646–53.

Warren O, Kinross J, Paraskeva P, Darzi A. Emergency laparoscopy – current best practice. World J Emerg Surg [Internet]. 2006 Aug 31 [cited 2019 Sep 8];1(1):24. Available from: http://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1749-7922-1-24.

Shaikh AR, Sangrasi AK, Shaikh GA. Clinical outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy. JSLS J Soc Laparoendosc Surg [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Sep 8];13(4):574–80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20202400.

Suh YJ, Jeong S-Y, Park KJ, Park J-G, Kang S-B, Kim D-W, et al. Comparison of surgical-site infection between open and laparoscopic appendectomy. J Korean Surg Soc [Internet]. 2012 Jan 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];82(1):35. Available from: https://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.4174/jkss.2012.82.1.35.

Gadacz TR. UPDATE ON LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY, INCLUDING A CLINICAL PATHWAY. Surg Clin North Am [Internet]. 2000 Aug 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];80(4):1127–50. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039610905702176.

Velanovich V. Laparoscopic vs open surgery. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2000 Jan [cited 2019 Sep 8];14(1):16–21. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004649900003.

Wang Y, Cui H, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Gasless laparoscopy for benign gynecological diseases using an abdominal wall-lifting system. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B [Internet]. 2009 Nov [cited 2019 Sep 9];10(11):805–12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19882754.

Lukban JC, Jaeger J, Hammond KC, LoBraico DA, Gordon AM, Graebe RA. Gasless versus conventional laparoscopy. N J Med [Internet]. 2000 May [cited 2019 Sep 8];97(5):29–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10832363.

Tintara H, Choobun T, Geater A. Gasless laparoscopic hysterectomy: A comparative study with total abdominal hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res [Internet]. 2003 Feb 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];29(1):38–44. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00074.x.

Goldberg JM, Maurer WG. A randomized comparison of gasless laparoscopy and CO2 pneumoperitoneum. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 1997 Sep 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];90(3):416–20. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0029784497002792.

Davila GW, Stanford E, Korn A. Prospective Trial of Gasless Laparoscopic Burch Colposuspension Using Conventional Surgical Instruments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc [Internet]. 2004 May 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];11(2):197–203. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1074380405601995.

Nakamura H, Kobori Y, Goseki N, Inoue H, Takeshita K, Endo M, et al. Fishing-rod-type abdominal wall lifter for gasless laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 1996 Sep [cited 2019 Sep 8];10(9):944–6. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00188492.

Zhang G, Liu S, Yu W, Wang L, Liu N, Li F, et al. Gasless laparoendoscopic single-site surgery with abdominal wall lift in general surgery: initial experience. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2011 Jan 7 [cited 2019 Sep 8];25(1):298–304. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00464-010-1177-9.

Wu J-M, Yang C-Y, Wang M-Y, Wu M-H, Lin M-T. Gasless Laparoscopy-Assisted Versus Open Resection for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors of the Upper Stomach: Preliminary Results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech [Internet]. 2010 Nov 6 [cited 2019 Sep 8];20(9):725–9. Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/lap.2010.0231.

Huang C-C, Yang C-Y, Wu M-H, Wang M-Y, Yeh C-C, Lai I-R, et al. Gasless Laparoscopy-Assisted Versus Open Resection of Small Bowel Lesions. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech [Internet]. 2010 Oct 12 [cited 2019 Sep 8];20(8):699–703. Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/lap.2009.0417.

Jiang J-K, Chen W-S, Wang S-J, Lin J-K. A novel lifting system for minimally accessed surgery: a prospective comparison between “Laparo-V” gasless and CO2 pneumoperitoneum laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2010 Aug 21 [cited 2019 Sep 8];25(8):997–1004. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00384-010-0942-5.

Jiang J-K, Chen W-S, Yang S-H, Lin T-C, Lin J-K. Gasless laparoscopy-assisted colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2001 Oct 15 [cited 2019 Sep 8];15(10):1093–7. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004640080148.

Ge B, Zhao H, Chen Q, Jin W, Liu L, Huang Q. A randomized comparison of gasless laparoscopic appendectomy and conventional laparoscopic appendectomy. World J Emerg Surg [Internet]. 2014 Jan 8 [cited 2019 Sep 8];9(1):3. Available from: http://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1749-7922-9-3.

Liao C-H, Kuo I-M, Fu C-Y, Chen C-C, Yang S-J, Ouyang C-H, et al. Gasless laparoscopic assisted surgery for abdominal trauma. Injury [Internet]. 2014 May 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];45(5):850–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020138313005184.

Hill DJ, Maher PJ, Wood EC. Gasless laparoscopy—Useless or useful? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc [Internet]. 1994 May 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];1(3):265–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1074380405810217.

Bossotti M, Bona A, Borroni R, Mattio R, Coda A, Ferri F, et al. Gasless laparoscopic-assisted ileostomy or colostomy closure using an abdominal wall-lifting device. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2001 Jun 19 [cited 2019 Sep 8];15(6):597–9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004640000268.

Ishida H, Hashimoto D, Inokuma S, Nakada H, Ohsawa T, Hoshino T. Gasless laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2003 Jun 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];17(6):899–902. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00464-002-9181-3.

Kawamura YJ, Sawada T, Sunami E, Saito Y, Watanabe T, Masaki T, et al. Gasless laparoscopically assisted colonic surgery. Am J Surg [Internet]. 1999 Jun 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];177(6):515–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002961099000951.

Kruschinski D, Homburg S, Langde S, Kapur A. Dermoid tumors of the ovary: evaluation of the gasless lift-laparoscopic approach. Surg Technol Int [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Sep 8];17:203–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18802903.

Munakata K, Uemura M, Shimizu J, Miyake M, Hata T, Ikeda K, et al. Gasless transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy as a safe and cost-effective alternative surgical procedure for mild acute appendicitis. Surg Today [Internet]. 2016 Mar 28 [cited 2019 Sep 8];46(3):319–25. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00595-015-1177-4.

Larsen JF, Svendsen FM, Pedersen V. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of pneumoperitoneum on cardiac function and haemodynamics during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg [Internet]. 2004 Jul [cited 2019 Sep 8];91(7):848–54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15227690.

Galizia G, Prizio G, Lieto E, Castellano P, Pelosio L, Imperatore V, et al. Hemodynamic and pulmonary changes during open, carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum, and abdominal wall-lifting cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2001 May 21 [cited 2019 Sep 8];15(5):477–83. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004640000343.

Tanaka H, Futamura N, Takubo S, Toyoda N. Gasless laparoscopy under epidural anesthesia for adnexal cysts during pregnancy. J Reprod Med [Internet]. 1999 Nov [cited 2019 Sep 8];44(11):929–32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10589402.

Bouvy ND, Marquet RL, Jeekel H, Bonjer HJ. Impact of gas(less) laparoscopy and laparotomy on peritoneal tumor growth and abdominal wall metastases. Ann Surg [Internet]. 1996 Dec [cited 2019 Sep 8];224(6):694–700; discussion 700-1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8968224.

Lee SC, Kim KY, Yoon SN, Kim BC, Kim JW. Feasibility of Gasless Laparoscopy-Assisted Transumbilical Appendectomy: Early Experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech [Internet]. 2014 Aug 25 [cited 2019 Sep 8];24(8):538–42. Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/lap.2013.0575.

Hyodo M, Sata N, Koizumi M, Sakuma Y, Kurihara K, Lefor A, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy using pneumoperitoneum or gasless abdominal wall lifting: A 15-year single institution experience. Asian J Endosc Surg [Internet]. 2012 May 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];5(2):63–8. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1758-5910.2011.00124.x.

Maas SM, Hage JJ, Cuesta MA. Less traumatic abdominal wall retraction for gasless laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2000 Aug [cited 2019 Sep 8];14(8):769–70. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004640010057.

Guido RS, Brooks K, McKenzie R, Gruss J, Krohn MA. A randomized, prospective comparison of pain after gasless laparoscopy and traditional laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc [Internet]. 1998 May 1 [cited 2019 Sep 8];5(2):149–53. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1074380498800819.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ [Internet]. 2015 Jan 2 [cited 2019 Sep 8];350:g7647. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25555855.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ [Internet]. 2011 Oct 18 [cited 2019 Sep 8];343:d5928. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22008217.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ [Internet]. 2016 Oct 12 [cited 2019 Sep 8];355:i4919. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27733354.

Mhairi C, McKenzie Joanne E, Amanda S, Vittal KS, Brennan Sue E, Simon E, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Jesudian Gnanaraj and Dr. Anurag Mishra for their support and direction on topic choice and advice on its significance to the global surgery community.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The design of the protocol and review was done by HS, SS, AP, and DL. The drafting of the protocol was done by HS, SS, and AP. All authors have contributed to the protocol editing and approval and DL has been guiding the project direction and choice of journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoman, H., Sandler, S., Peters, A. et al. Safety and efficiency of gasless laparoscopy: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 9, 98 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01365-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01365-y