Abstract

Background

About 5.8 million maternal deaths, neonatal deaths and stillbirths occur every year with 99% of them taking place in low- and middle-income countries. Two thirds of them could be prevented through cost-effective interventions during pregnancy, intrapartum and postpartum periods. Despite the availability of standards and guidelines for the care of mother and newborn, challenges remain in translating these standards into practice in health facilities. Although several quality improvement (QI) interventions have been systematically reviewed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) group, evidence lack on QI interventions for improving perinatal outcomes in health facilities. This systematic review will identify QI interventions implemented for maternal and neonatal care in health facilities and their impact on perinatal outcomes.

Methods/design

This review will look at studies of mothers, newborn and both who received inpatient care at health facilities. QI interventions targeted at health system level (macro), at healthcare organization (meso) and at health workers practice (micro) will be reviewed. Mortality of mothers and newborn and relevant health worker practices will be assessed. The MEDLINE, Embase, World Health Organization Global Health Library, Cochrane Library and trial registries electronic databases will be searched for relevant studies from the year 2000 onwards. Data will be extracted from the identified relevant literature using Epi review software. Risk of bias will be assessed in the studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized and observational studies. Standard data synthesis and analysis will be used for the review, and the data will be analysed using EPPI Reviewer 4.

Discussion

This review will inform the global agenda for evidence-based health care by (1) providing a basis for operational guidelines for implementing clinical standards of perinatal care, (2) identify research priorities for generating evidence for QI interventions and (3) QI intervention options with lessons learnt for implementation based on the level of needed resources.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO registration number CRD42018106075

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The call under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to reduce maternal mortality to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, the global neonatal mortality rate to 9 per 1000 live births and global stillbirth rate to 9 per 1000 births by 2030 has led to widespread attention on increasing the coverage of live-saving interventions for mothers and babies [1,2,3,4,5].

If the current annual rates of reduction continue, by 2030, 116 million more mothers and babies will die with 99 million having lost development potential (including 31 million disabled), and the targets set for 2030 will be missed [6].

The availability of standard guidelines for the care of mother during pregnancy, intrapartum and postpartum period is very important to accelerate the rate of reduction in deaths [7, 8]. The translation of standard guidelines into routine health worker practices requires strong support and systems in health facilities [9,10,11].

A strategic pillar of the global Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP) is to ensure the quality of care for mothers and newborn through quality improvement interventions [1, 12]. However, despite the call through the ENAP and WHO’s Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality Strategy (2015) to invest more in improving quality of care, poor health worker performance continues to compromise the care of mothers and newborn [13, 14].

Optimal health care requires much more than providing infrastructure, drugs, supplies and health care providers [15]. It needs a focus on delivering quality services that are effective, safe, people-centred, timely, equitable, integrated and efficient [16]. Quality of care is the degree to which health services increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes in line with current professional knowledge [17].

The Millennium Development Goal (MDG) period (2000–2015) saw accelerated progress on achieving global health goals [18]. Maternal mortality fell by 43% [19], although progress was unequal with preventable mortality remaining high among poor, rural and hard-to-reach populations [20]. There was significant difference in low and middle-income countries in the neonatal mortality rate for babies born in the poorest and richest households, between babies of less and most educated mothers, and between babies in rural and urban areas [21, 22]. A study conducted in India reports that although the number of institutional deliveries in Madhya Pradesh, India increased from 14% in 2005 to 80% in 2010, there was no reduction in maternal and child mortality due to poor quality care at health facilities [23].

Poor health worker performance is a fundamental cause of poor-quality care. A host of factors are associated with poor health worker performance [10, 24]. Macro-level health system factors include inadequate budgets for human resources, supplies, administrative structures and for information systems to inform decision making [25]. Meso-level health facility factors include inadequate leadership, the absence of quality improvement processes, heavy client loads, lack of health worker participation in planning and organizing work, and lack of educational opportunities for health workers [26,27,28]. Micro-level factors include inadequate health worker skills, motivation and job satisfaction and fear of bad clinical outcomes [29, 30]. Micro-level client-related factors include the severity of illnesses, level of patient demand and demographic factors [31]. These factors hinder the implementation of QI standards and need addressing through context-specific interventions.

There have been several systematic reviews on QI interventions for improving health worker performance [10, 11]. These have shown that the effectiveness of interventions depends on type complexity of the delivering the interventions. Different interventions have been identified for implementing care standards, with their effects varying by context, type of health worker and type of behaviour [32].

More than 100 systematic reviews conducted by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group on QI interventions for improving health worker performance [33,34,35]. These reviews found that the continuous education of health workers promotes good compliance with care standards, with other interventions only leading to moderate improvements in quality of care [32]. Educational outreach to health workers, educational materials and audit and feedback on performance have only had moderate effects on improving quality of care [36,37,38]. However, there is very little evidence on the effects of QI interventions at the macro health system level, and only limited evidence at the healthcare organization level, with a better evidence on effects at the client level [39, 40].

In 2018, to guide countries on how to better implement standards of care to achieve the health-related SDGs, the World Bank, WHO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified four types of quality improvement interventions by the level of governance [16].

The availability of evidence at meso and micro levels mostly exists on tailor-made interventions, such as for diabetic care, and general health service delivery. The evidence of which QI interventions work at which level of governance for improving maternal and neonatal care is, however, limited. A 2017 systematic review on QI interventions for a small and sick newborn in low- and middle-income settings identified a number of QI interventions for improving care in sick newborn care units [40].

This systematic review will identify interventions implemented for maternal and neonatal care in health facilities and their impact on perinatal outcomes.

Methods/design

Reporting of review findings

This systematic review will use the reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses protocols (PRISMA-P) guideline for reporting [41] and EPOC Cochrane methods [33]. The PRISMA-P checklist is provided at Additional file 1.

Data source and search strategy

The review will search the Medline, Embase, WHO Global Health Library and Cochrane Library electronic databases from 2000 onwards to identify relevant studies. The review will also search the trial registries of WHO, WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) and ClinicalTrials.gov for completed and ongoing studies. The searches of peer-reviewed publications will be supplemented by scanning the reference lists of relevant studies and systematic reviews. The grey literature will be searched using the databases of WHO technical reports on quality of care, UNICEF field implementation and evaluation reports and Department for International Development (DFID) technical reports. Articles with either abstracts or full text in English, Spanish, French and Chinese and published from 2000 onwards will be searched. The detailed search strategy is provided in Additional file 2.

Eligibility criteria

The eligible population groups are systems or organizations or providers who care for mothers or newborns in inpatient settings.

Intervention

Quality improvement is defined as the implementation of measures either together or standalone to improve the quality of care provided to mothers and/or newborn. As per the EPOC and WHO-OECD-World Bank frameworks, the QI interventions will be categorized into macro, meso and micro levels. See details in Table 1.

Comparison

The comparison group will either be no QI intervention or an intervention that has not improved the quality of care for mothers and newborn.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

-

Maternal mortality refers to deaths due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth

-

A stillbirth is a baby born with no signs of life at or after 28 weeks of gestation

-

An antepartum stillbirth refers to where a baby dies in the womb during pregnancy and before labour or in utero 12 h before delivery

-

An intrapartum stillbirth refers to where a baby dies during labour or in utero within 12 h before delivery

-

First-day mortality refers to neonatal mortality within 24 h of birth

-

First seven-day mortality refers to early neonatal mortality or the death of newborn babies within the first 7 days of life

-

First 28-day mortality refers to late neonatal mortality or the death of newborn babies between 7 and 28 days of being born

-

Pre-discharge mortality refers to where a baby dies before being discharged from health facilities

Secondary outcomes

-

The foetal heart rate during the intrapartum period

-

Infection prevention practices during labour, delivery and neonatal period

-

Skin to skin contact between mother and baby in the first hour of life

-

Neonatal resuscitation

-

Kangaroo mother care

-

Early breastfeeding

-

The treatment of in-patient neonatal infection

-

Duration of hospital day

-

Client satisfaction

Selection of studies

The review will consider the following types of studies on quality improvement interventions for perinatal care in health facilities [42]:

-

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) at cluster and individual levels.

-

Observational studies including cross-sectional studies, cohort studies and interrupted time series design studies.

-

Quasi-experimental studies, including research and evaluation studies in which participants were not randomly assigned to treatment conditions, but in which comparison groups were constructed by statistical means.

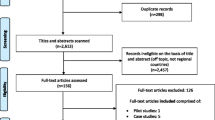

Data collection

Two of the overview authors (AK and JT) will independently screen titles and abstracts found in EPI-Review to identify reviews that may meet the inclusion criteria. Two other authors (AKC and SSB) will screen all titles and abstracts that cannot be confidently included or are excluded after the first screening to identify any additional eligible reviews. One overview author will screen the reference lists.

One overview author (AK or JT) will apply the selection criteria to the full texts of potentially eligible reviews and assess the reliability of reviews that meet all other selection criteria. Two other authors (AKC and SSB) will independently check these judgments.

Data extraction

The review will use standard forms to extract data from research on the background of the study: interventions, participants, settings, outcomes, key findings, considerations of applicability, equity, economics, and monitoring and evaluation. The review will assess the certainty of the evidence for the main comparisons using the GRADE approach.

A standardized pre-piloted data extraction form will be developed by the team and tested on 20 articles and revised iteratively as needed. Information will be extracted on the following:

-

Study setting—Region, country, location (urban/rural), level of health facility (primary, secondary or tertiary)

-

Study design—Randomized control trial, observational study (cross-sectional, cohort, case-control studies), or quasi-experimental study

-

Method of data analysis—Descriptive analysis of frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation with inferential statistics through chi-squared test and logistic regression

-

Quality improvement interventions—Facilitation, continuing education events, audit and feedback, reminders, checklists, outreach visits and financial incentives

-

Duration of intervention

-

Participants—study population, number of participants in each group and patient characteristics

-

Outcomes—primary and secondary outcomes

Quality assessment

Risk of bias and the quality of individual studies will be assessed using Cochrane risk of bias (ROB) tool for randomized studies [43] and Risk of Bias tool for non-randomized studies (RoBANS) [44] and Cochrane appraisal tool for qualitative research [45]. The use of this tool will address random sequence generation bias, allocation concealment bias, selective reporting bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other biases. These will be further categorized as low, high or unclear risk of bias based on the type of response. This task will be completed by AKS and JT.

Data synthesis and analysis

It is anticipated that the selected studies will have a variety of research designs that use qualitative and quantitative methods. The results from the studies will be summarized and tabulated according to the following key headings:

-

Information on overarching approaches for improving the quality of health care of mothers and newborn.

-

Information on whether and how the approaches for QI relate to specific signal functions for maternal and newborn care.

-

The efficacy and effectiveness of the efforts to improve maternal and newborn care.

-

The process and outcomes used as measures of quality improvement.

-

Where possible, results will be disaggregated according to geography (regional, sub-national levels), wealth quintile, rural or urban setting, public or private health facility and type of health facility.

Meta-biases

Research studies can have implementation and design bias, which will be referred to as meta-biases [46, 47]. Funnel plots will be done when a number of studies go beyond 10 to assess reporting bias [48].

Confidence in cumulative evidence

GRADE criteria will be used to assess the quality of studies and reporting done in the studies [49]. GRADE provides a clear and comprehensive methodology for rating and summarizing quality of evidence and thus supports management recommendations [50]. GRADE assigns high, moderate, low, and very low levels of evidence quality. For qualitative studies, the GRADE-CERQual (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) will be used [51].

Randomized trials generally begin as high-quality evidence and observational studies as low-quality evidence. The quality of evidence may be subsequently downgraded as a result of limitations in study design or implementation, imprecision of estimates (wide confidence intervals), variability in results, indirectness of evidence or publication bias. Quality may be upgraded because of a very large magnitude of effect, a dose-response gradient and if all plausible biases would reduce an apparent treatment effect. Quality assessments will be undertaken by two independent researchers. Any discrepancies will be resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

The framework will thus examine the quality of methodology, the relevance of methodology and the relevance of evidence to the issue under review. An average of these weightings will be taken to establish the overall weight of evidence of each study.

Discussion

This systematic review has three implications. First, it will identify evidence on QI interventions implemented to improve the care of mothers and newborn in health facilities and provide further evidence on the impact of QI interventions on quality of care. The evidence on the impact on care on maternal and neonatal care will enable an implementation framework on quality improvement to be developed. This framework can then be used to develop overall operational guidelines for implementing standards of care for mothers and newborn in different health care settings.

Second, the types of QI interventions identified will indicate gaps in the evidence base for informing decision-making on QI interventions. The review will identify research gaps on QI interventions for improving care to identify subjects that need researching.

Third, the evidence of the impact of QI interventions on improving care will provide guidance to governments and other stakeholders on the resources needed to implement QI interventions for the more effective care of mothers and babies.

The QI interventions in this review will discuss the context of implementing the interventions. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [52, 53] with its five domains; namely, characteristics of the intervention, individuals, inner setting, outer setting and implementation process will help facilitate the discussion of the context in which the intervention has been implemented. Many governments struggle to justify the investments needed to further improve maternal and neonatal health care against competing demands to spend more on combatting non-communicable diseases, re-emerging infectious diseases and other priorities. There is a need for an implementation framework for QI interventions for maternal and neonatal care. This systematic review will be an evidence-based reference document for WHO, UNICEF and other global health care partners to develop implementation guideline.

Abbreviations

- EPOC:

-

Effective Practice and Organization of Care

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- MDG:

-

Millennium Development Goal

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organisation. Every newborn, vol. 58. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

World Health Organization. Every newborn action plan: country progress tracking report. 2015.

World health Organization. Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM), vol. 6736. Geneva: WHO; 2015. p. 1–4.

Partnership for Maternal N& CH, Member. 2017 progress on the Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy; 2017. p. 1–79.

World Health Organization. Health in 2015: from MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals, vol. 204. World Health Organization; 2015.

Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, You D, Lee ACC, Waiswa P, et al. Every newborn: Progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):189-205.

World Health Organization. Pocket book of hospital care for mothers, Guidelines for management of common maternal conditions. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2017.

World Health Organization. Essential interventions, commodities and guidelines for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 12–6.

Haines A, Kuruvilla S, Borchert M. Bridging the implementation gap between knowledge and action for health. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(10):724-31.

Rowe AK, de Savigny D, Lanata CF, Victora CG, Black R, Morris S, et al. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? Lancet (London, England). 2003;366:1026–35 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16168785.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39:2–45.

Mason E, McDougall L, Lawn JE, Gupta A, Claeson M, Pillay Y, et al. From evidence to action to deliver a healthy start for the next generation. Lancet. 2014;384(9941):455–67.

Dickson KE, Simen-Kapeu A, Kinney MV, Huicho L, Vesel L, Lackritz E, et al. Every newborn: health-systems bottlenecks and strategies to accelerate scale-up in countries. Lancet. 2014;384(9941):438–54.

Sharma G, Powell-Jackson T, Haldar K, Bradley J, Filippi V. Quality of routine essential care during childbirth: clinical observations of uncomplicated births in Uttar Pradesh, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(6):419–29.

Ministry of Health. Quality improvement structures in Nepal – options for reform. 2017;

World Health Organization. Delivering quality health services. Geneva: 2018. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bookorders.

Tunçalp Ӧ, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborn-the WHO vision. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;122:1045–9. Available from: doi.wiley.com/10.1111/1471-0528.13451.

Boerma T, Requejo J, Victora CG, Amouzou A, George A, Agyepong I, et al. Countdown to 2030: tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1538-48.

Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Dandona L, Gething PW, Hay SI, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775-812.

Tudor HJ. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;297:405–12.

Berhan Y, Berhan A. Reasons for persistently high maternal and perinatal mortalities in Ethiopia: part II-socio-economic and cultural factors. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24(Suppl):119-36.

Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, Begkoyian G, Fogstad H, Walelign N, et al. Neonatal Survival Series 3. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care: what will it take in the reality of countries? Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1087–98.

Ng M, Misra A, Diwan V, Agnani M, Levin-Rector A, De Costa A. An assessment of the impact of the JSY cash transfer program on maternal mortality reduction in Madhya Pradesh, India. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24939.

Gera T, Shah D, Garner P, Richardson M, Sachdev HS. Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) strategy for children under five. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD010123.

Bryce J, El Arifeen S, Pariyo G, Lanata CF, Gwatkin D, Habicht JP. Reducing child mortality: can public health deliver? Lancet. 2003;362(9378):159–64.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & World Health Organization. Caring for quality in health: lessons learnt from 15 reviews of health care quality. Rev Heal Care Qual. 2017. Geneva.

Kc A, Wrammert J, Clark RB, Ewald U, Vitrakoti R, Chaudhary P, et al. Reducing perinatal mortality in Nepal Using Helping Babies Breathe. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6).

Rowe AK, Onikpo F, Lama M, Osterholt DM, Rowe SY, Deming MS. A multifaceted intervention to improve health worker adherence to integrated management of childhood illness guidelines in Benin. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):837–46.

Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, Ivey Boufford J, Brown H, Chowdhury M, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–90.

Lange S, Mwisongo A, Mæstad O. Why don’t clinicians adhere more consistently to guidelines for the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)? Soc Sci Med. 2014;104:56–63.

Awor P, Wamani H, Bwire G, Jagoe G, Peterson S. Private sector drug shops in integrated community case management of malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea in children in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(5 Suppl):92–6.

Grimshaw J, McAuley LM, Bero LA, Grilli R, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, et al. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(4):298–303.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)-Cochrane. What study designs should be included in an EPOC review and what should they be called. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Resources for review authors, 2017. Available at: epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

Mowatt G, Grimshaw JM, Davis DA, Mazmanian PE. Getting evidence into practice: the work of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC). J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2001; Winter;21(1):55–60.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). The EPOC taxonomy of health systems interventions. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2016.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

Giguere A, Legare F, Grimshaw J, Turcotte S, Fiander M, Grudniewicz A, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes [Systematic Review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD004398.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Jm Y, Sd F, Ma OB, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (Review). Cochrane Libr. 2012;(6):CD000259.

Pantoja T, Opiyo N, Lewin S, Paulsen E, Ciapponi A, Wiysonge CS, et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: An overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011086.

Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(3):226–40.

Zaka N, Alexander EC, Manikam L, Norman ICF, Akhbari M, Moxon S, et al. Quality improvement initiatives for hospitalised small and sick newborn in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:20.

Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M. How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(5):325–36.

Higgins Julian PT, Altman Douglas G, Gøtzsche Peter C, Peter J, David M, Oxman Andrew D, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo H-J, Sheen S-S, Hahn S, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies (RoBANS) showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–14.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Hannes K, Noyes J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance paper 4: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:35–8.

Fanelli D, Costas R, Ioannidis JPA. Meta-assessment of bias in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(14):3714–9.

Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D, Vandenbroucke JP, Irwig L, Macaskill P, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1998;316(7129):469.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta¬analysis detected by a simple , graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction - GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence - Inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1294–302.

Colvin CJ, Garside R, Wainwright M, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Bohren MA, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 4: how to assess coherence. Implement Sci. 2018;13(Suppl 1):13.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2016;11:72.

Funding

Golden Community supported the salary of RG and AKS for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AKC and NZ conceptualized this study protocol. RG made the first draft while SSB and AKC contributed expertise on the methods. RG, AK, SSB, HZ and NZ finalized the eligibility criteria. SSB and AKS developed search terms. AKS and JT will search the databases, combine results, remove duplicates, and prepare the initial part of the PRISMA flow diagram. AKS, RG and JT will extract the data and AK and SSB will analyse the data. SSB, RG, AKS, JT and HZ provided input to produce this protocol and agreed to this final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-P Checklist: Impact of Quality improvement intervention(s) on perinatal outcome in health facilities: a systematic review. (DOCX 20 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search strategy. (DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gurung, R., Zaka, N., Budhathoki, S.S. et al. Study protocol: Impact of quality improvement interventions on perinatal outcomes in health facilities—a systematic review. Syst Rev 8, 205 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1110-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1110-9