Abstract

Background

A recent paradigm shift within the intensive care discipline has led to implementation of protocols to drive early recovery from the intensive care unit (ICU). These protocols belong to a large knowledge, translation and quality improvement initiative lead by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, aiming to “liberate” patients from the ICU. They “bundle” evidence-based elements shown to lower ICU stay and mortality and optimize pain management. The bundled elements focus on Assessing, preventing and managing pain; Both spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; assessment, prevention, and management of Delirium; Early mobility and exercise; and Family engagement and empowerment (ABCDEF). It is evident that analgesia and sedation protocols either directly relate to or influence most of the bundle elements. A paucity of literature exists for neurologically injured patients, who create unique challenges to bundle implementation and often have limited external validity in existent studies. We will systematically search the literature, present the unique challenges of neurointensive care patients, conduct a stratified analysis of subgroups of interest, and disseminate the evidence of analgesia and sedation protocols in the neurointensive care unit (NICU). We hope the relevant stakeholders can adapt this information through knowledge translation—to make formal recommendations in clinical practice guidelines or a position statement.

Methods/design

The authors will search MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Cochrane Clinical Trials Registry, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, and the National Institutes for Health Clinical Trials Registry. The title, abstract, and full-text screening will be completed in duplicate, and a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of agreement will be reported. Provided the data retrieved from studies is suitable, results will be combined statistically using meta-analysis. We aim to evaluate the impact of ABCDEF bundle components on multiple endpoints of NICU recovery. Our primary outcomes will be time to successful discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and time to early mobility. The authors will guide the methodological design of the study using the PRISMA-statement and the checklist compliance will be available.

Discussion

Using the evidence from this systematic review, we anticipate disseminating knowledge of analgesia and sedation protocols in the NICU. The results of this systematic review are imperative to close the knowledge gap in a patient population that is often excluded from studies, and to add to the body of literature aiming to enhance early recovery from the NICU and mitigate iatrogenic harm.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42017078909

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is a growing body of knowledge that contributes to our understanding of the devastating outcomes of critical illness [1]. It is through such rigorous investigations that we learned our iatrogenic contribution to patient morbidity and mortality. A prominent example is unoptimized mechanical ventilation up until the 1990s and the development of the ARDSnet protocol [2, 3] which has since saved thousands of lives of those mechanically ventilated in the intensive care unit (ICU). A clinical area left largely unexplored is analgesia and sedation practices in the ICU. Although the practice has evolved in the last decade, many of our current clinical decisions are not strongly supported by high quality (level 1) evidence [4]. The paucity in evidence could be explained by difficulty in trial design, simultaneous use of several pharmacologic agents leading to a confounding effect, and heterogeneity in ICU patient populations leading to limited external validity [4]. Sedation practices have been shown to influence extubation and mortality [5]. In light of our growing understanding of analgesia and sedation practices contributing to iatrogenic harm, current practices and their outcomes have been the subject of a large body of research. One complication that has been shown to increase morbidity is ICU-related cognitive impairment [6, 7]. Certain risk factors for this ICU-acquired phenomenon that has been termed “post-intensive care syndrome” (PICS) include delirium [8], pain, and agitation (PAD), which are commonly experienced [9,10,11]. Furthermore, pain has been shown to be the largest concern of patients, and its recall has been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, and reduced quality of life after discharge. With more than 4 million ICU admissions per year [8], the overall impact on those patients who survive ICU stay can be significant. ICU stay has been associated with long-term cognitive, psychological, neuromuscular, and functional deficits all of which contribute to PICS, which can leave patients with a significantly impaired quality of life post-discharge [12,13,14,15,16].

Pain was once considered the “fifth vital sign,” and this approach has been recently scrutinized in light of the growing concern of the modern opioid epidemic and fatal respiratory depression events attributed to liberal sedation practices [17]. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) recommendations for pain assessment and treatment in hospitalized patients [17, 18] were revised since their inception in 2000, with the latest iteration in 2017. The current standards advocate for multi-modal analgesic regimens. These regimens include setting realistic pain expectations, identifying psychosocial factors that may affect self-report of pain, rigid prescription accountability, vigilant monitoring of high-risk patients, and implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs [19]. In 2013, the American College of Critical Care Medicine revised its 2002 clinical practice guidelines of pain, agitation, and delirium (PAD) of adults in the ICU to reflect ‘analgosedation’ sparing practices [20]. There is new evidence to support the paradigm shift of minimizing analgosedation in the ICU. One parallel-design RCT [21] demonstrated that immediate sedation interruption in the ICU resulted in statistically and clinically significant expedited extubation, reduced time on mechanical ventilation, delirium, and coma.

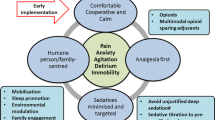

Efforts by the Society of Critical Care Medicine aim to optimize pain management while reducing delirium and long-term adverse consequences of ICU admission. This quality improvement and knowledge translation initiative known as “ICU liberation” sets its foundation on “bundling” several elements shown to expedite mechanical ventilation weaning and encourage early mobility [13]. These bundled elements focus on Assessing, preventing, and managing pain; Both spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; assessment, prevention and management of Delirium; Early mobility and exercise; Family engagement and empowerment (ABCDEF). There is an abundance of evidence to support spontaneous awakening and breathing trials [22,23,24,25]; provide light sedation to maintain patients at an awake and alert level and avoidance of benzodiazepines [26,27,28,29,30,31]; assess, prevent, and manage delirium [32,33,34,35,36]; encourage early mobility and exercise [37,38,39,40,41] (a dogma that was once implemented, abandoned, and now rediscovered [13]); and engage and empower families [42,43,44].

A cross-sectional study [45] with 143 mechanically ventilated patients in a single-center ICU compared participants with bundle implementation (A through E) [n = 73] to those without [n = 70]. The authors found a statistically significant [p < 0.05] improvement in hemodynamics at 3, 5, and 7 days after bundle implementation (mean arterial pressure, central venous pressure, heart rate), oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2), reduced requirement of Sufentanil and Midazolam, reduced delirium, improved 28-day survival, and reduced mechanical ventilation duration and total ICU length of stay. Despite the strong evidence advocating for ABCDEF bundle implementation, there is still low compliance amongst international ICUs. A large international survey [46], with 1521 ICUs respondents across 47 countries, showed that only 57% reported to implement the ABCDEF bundle. A recent large cohort study that surveyed six ICUs and 6064 patients (of which 1438 received mechanical ventilation and thus the ‘full ABCDEF bundle implementation’) [1] demonstrated a statistically significant reduction of delirium and mortality with bundle implementation (a 15% higher hospital survival for every 10% increase in partial bundle compliance). Average ICU mortality in adults, estimated at 10–29%, varies according to population traits such as age, comorbidities, and illness severity [47]. There seems to be a dose-response relationship between bundle compliance and favorable patient outcomes such as reduced ICU mortality and increased hospital survival. The aforementioned study [1] is the largest we are aware of that directly measures cohort outcomes of ‘pre- and post-ABCDEF bundle implementation’ and thus offers quantitative data for its benefits.

It is clear that the choice of analgesic modality influences most bundle elements. For example, several pharmacological elements indicated for analgesia may also confound respiratory drive, mechanical ventilation weaning, development of delirium, and ability to mobilize early. A group that is often excluded from studies is neurologically injured adults [48], thus limiting the generalization of the results and threatening the external validity in the NICU. Guidelines exclude neurologically injured patients for safety reasons [20]. The most obvious safety concern arises in the setting of high intracranial pressure (ICP). Moreover, in the NICU, sedatives and analgesics serve as therapy to lower ICP, prevent brain compression and subsequent herniation. Additionally, patients with raised ICP are not candidates for a spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, as these maneuvers can further exacerbate raised ICP. Analgesia and sedation practices indeed create a unique challenge in the NICU setting as it may influence the neurological exam, and arousal in patients whose central nervous system has already been injured. An important component of neuromonitoring in the NICU is the gold-standard serial neurological wake-up tests [49]. Other challenges include balancing a neurological exam versus optimizing neurologic parameters such as cerebral blood volume, ICP, cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen and seizure control both in terms of prophylaxis or treatment [18, 48, 50, 51]. Additionally, an underlying neurological condition may affect patients’ ability to communicate, mobilize, breathe, and impact their pain threshold, all of which are directly related to and influence liberation from the NICU.

We identified a paucity of literature with respect to neurologically injured adults receiving intensive care, which has resonated in earlier reports [9]. Additionally, no other study to our knowledge explored challenges to ABCDEF bundle implementation in the NICU. Furthermore, a recently published international survey and practice audit of six NICUs showed discordance in physician self-reporting, and thus analgesia regimens require further work for optimization [52]. This systematic review will investigate the components of the ABCDEF bundle as they are applied to neurologically injured adults and explore evidence of challenges experienced in analgosedation practices in the NICU.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to identify the challenges of analgesia and sedation in the context of the ABCDEF bundle implementation in the NICU. The only systematic review we found that addressed barriers to ABCDEF implementation [53] was not specific to the unique considerations of neurologically injured adults. Provided that most studies exclude this patient population, a study that elucidates the external validity of bundle implementation to the NICU is warranted. Furthermore, our goal is to “unbundle” the liberation components that older studies might have addressed individually and pool their results.

Specifically, the objectives of this investigation include:

-

1)

Assessing the transferability of ABCDEF bundle components to patients admitted to the NICU

-

2)

Compare the efficacy of different analgesic and sedation modalities across ventilation weaning, early mobilization, and post-discharge outcomes amongst patients admitted to NICU

-

3)

Determine whether particular analgesic and sedation agents or regimens optimize outcomes in patients admitted to the NICU when stratified for various neurological disorders

-

4)

Critically evaluate the current literature and identify important knowledge gaps that future research should address

-

5)

Offer evidence to be used for knowledge translation by relevant stakeholders

-

6)

Publish the final report in an open access journal to eliminate restrictions to knowledge dissemination

We are interested in the analgesia and sedation regimens in the NICU, and hope the preliminary findings of this systematic review will set the groundwork to further clinical questions and research addressing each component of the ABCDEF bundle.

Research question

In the neurologically injured adult receiving neurointensive care, does implementation of the ABCDEF bundle or its individual parts, improve time to wean off mechanical ventilation, time to mobilization, and reduce long-term complications associated with intensive care therapy?

Please refer to Table 1 for the PICO question used to derive our research question.

Methods/design

We will conduct a comprehensive search of the available literature. In order to broaden our capture strategy, we will not include outcomes (e.g., mortality, post-intensive care syndrome) in our search strategy and rather screen for these outcomes during the study extraction process with an identical checklist that will be developed by consensus of the two screeners (ME and BD) and approved by all the remaining of the authors. We will search the following online databases: MEDLINE (Ovid)/PubMed, EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Library, Cochrane Clinical Trials Registry, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, and the National Institutes for Health (NIH) Clinical Trials Registry. We will use a university library subscription accessed through (library.sgul.ac.uk/). The search terms were agreed upon by consensus, and MeSH and Emtree terms were included for completeness and to broaden the search in case articles were incompletely indexed by the databases. The team agreed it was preferable to have redundant search terms to broaden the search and narrow the study selection during the screening phase. Searches will be performed independently by two authors (ME and BD). We will not be searching the gray literature with the exception of official material published on the Society of Critical Care Medicine ICU Liberation website (http://www.iculiberation.org). We will also contact each primary investigator listed on the NIH Clinical Trial Registry from studies deemed eligible during the title screening, where we will inform the investigators of our systematic review and ask for information regarding any publications resulting from their trial. We consulted a librarian from the Scott Memorial Library of Thomas Jefferson University with expertise in systematic reviews to assist with the process of devising the search strategy and conduct the literature search. The two authors (ME and BD) will then independently manually scan the bibliography of all studies that met the inclusion criteria to ensure no relevant titles were missed. Only studies published in the English language will be extracted. We will constrain the search for studies published after 1992. Only human studies will be included. We will also eliminate incomplete studies, as they would not provide sufficient data for extraction. We will inform the authors of the eligible articles about the review during the data extraction process to consult them for clarification of their data when needed. Please refer to Table 2 for the full search strategy, which may be subject to minor revisions for the final systematic review.

Selection of studies

The authors (ME and BD) will independently conduct a primary title search, title screening, abstract screening, and full-text extraction. We will refer to the inclusion and exclusion criteria throughout the screening process and reject articles that are not relevant. We will utilize the DistillerSR (https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/) to screen titles and abstracts extracted across all the database searches. In the case of a disagreement during the search and selection process, we will engage in discussion to reach a consensus. Should a conflict persist, a third author (DW) will facilitate the resolution. Agreement level between reviewers will be assessed using the Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. As per guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA), a flow diagram will be included to display the screening process (Fig. 1) and a detailed table of the studies selected in the systematic review [54].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The authors will limit the studies to be included in this review to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and high-quality observational (prospective or retrospective-cohort) studies evaluating the implementation of any of the ABCDEF bundle elements (either individually or together) in the NICU. Specifically, the study would have had to examine any of the following in adults (≥ 18 years old) in the context of a neurological injury. (1) assessment of pain management, (2) spontaneous awakening trials and/or spontaneous breathing trials, (3) analgesia and sedation (4) delirium, (5) early mobility and/or exercise, (6) family engagement and/or empowerment. The study participants may be spontaneously breathing, assisted, or mechanically ventilated, receiving any form of analgesia with or without concomitant use of agents primarily indicated for sedation, and with or without use of alternative non-pharmacological therapies. The PRIMARY outcomes are measured in a unit of time. We will define wean as a successful cessation of mechanical ventilation for more than 24 h. While mobility or animation has been defined as “getting patients out of bed” and walking (even if intubated and mechanically ventilated) [13], this approach of active patient engagement does not necessarily capture the challenges of patients with neurological injury, whose paresis, paralysis, spasticity, and neuropathic pain may impede on this goal. We will define mobilization as any attempt to engage in assisted walking or physical exercise or physical therapy such as passive range of motion exercises. Patients in the NICU may indeed benefit from passive range of motion as therapy for contractures, pain, and enhance their probability to eventual ‘active mobility.’

We will set exclusion criteria to control for bias and confounding variables such as a severe neurological injury that prevents outcome measures (e.g., irreversible neurological injury or persistent vegetative state), expected mortality < 7 days or palliative care, a severe baseline (pre-NICU admission) neurocognitive deficit (such as dementia or a severe intellectual disability). All studies must be primary investigations with comparison groups. We will not include pilot studies or RCTs at phases 0, 1, and 2. Case reports and case series will be excluded from our review due to their low external validity. All studies selected for inclusion into our manuscript will be required to demonstrate an ethics review board approval in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Statistical analysis plan and quality assessment of individual studies

Results from this review will be summarized both narratively and statistically using meta-analysis where possible. When statistical pooling of results from included studies is not feasible, we will summarize our findings narratively by reporting the individual descriptive statistics from included studies. Summary estimates will be calculated using the pooled standardized mean differences for continuous outcomes and pooled odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes. All summary estimates will be presented in forest plots. Due to the anticipated heterogeneity in the study populations, a random-effect meta-analysis with a DerSimonian Laird estimator will be used. All studies will be weighted according to the inverse of the variance. As it is highly cautioned against to pool experimental (randomized) and non-randomized studies, we will require studies to share the same research methodology. In efforts to reduce the impact of selection bias on the pooled estimates, we will require studies to share the same research design (e.g., RCT) when included in the meta-analysis [55, 56].

Provided an appropriate number of studies are eligible for inclusion, we will assess for publication bias using an Egger’s plot.

We will rely on the I2 statistic to interpret the level of heterogeneity affecting the pooled meta-analysis findings. To interpret the I2, we will use thresholds set forth by the Cochrane Collaboration, these include I2 of 0–40% (might not be important), 30–60% (moderate heterogeneity), 50–90% (substantial heterogeneity), and 75–100% (considerable heterogeneity) [55].

The differences in the patient population as well as methodological quality are anticipated to be important factors for explaining heterogeneity between studies. Provided we have a suitable number of studies, we will conduct subgroup analyses (whenever data is available) to assess the robustness of our meta-analysis findings when stratified by (1) methodology quality based on the risk bias assessment scores, (2) category of neurological disorder, injury, or admission diagnosis to the NICU, (3) neurological injury assessment tools such as the Glasgow Coma Scale, (4) whether the patients received mechanical ventilation, (5) BMI, (6) age, (7) baseline opioid usage and indication. The differences in methodological quality will be captured using the scores obtained from the risk of bias assessment, using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs. Utilizing the scores attained during the risk of bias assessment, studies will be categorized into high or low methodological quality using the standard methodological scoring cut-offs used in previous reviews [57]. We anticipate that the implementation of optimal analgesia and sedation regimens within different subgroups in the NICU to differ for a multitude of reasons, and therefore, it is important to compare the statistical outcomes of subgroups of patients receiving neurointensive care. First, patients receiving mechanical ventilation are by definition of those who we are seeking to ‘liberate’ from the NICU. Comparing them to those who are not mechanically ventilated can shed light into optimizing analgesia and sedation regimens specific to this subgroup. Patient characteristics such as age, BMI, and baseline opioid usage may affect opioid sensitivity and may warrant their stratified analysis for the primary and secondary outcomes. Furthermore, we will critically examine whether a malignancy diagnosis poses challenges to analgesia and ICU liberation as there are unique consideration when treating “cancer pain.” This may provide new insight into challenges of particular patient populations and pave the path to new research to assist in their recovery from the NICU.

All analyses will be performed using STATA Version 13.

GRADE framework

We will assess the quality of evidence using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [58]. Most importantly, we will scrutinize the quality of evidence as has been described in the original publications from the GRADE Working Group [59]. We will include a reference table in our proposed review for readers to easily visualize what the different quality measurements that we refer to are defined by.

Discussion

There are some concerns with respect to the choice of analgesic modalities in the NICU. Opioid addiction has been shown to be as high as 44% in those receiving long term infusions [60]. Strikingly, opioids have been found to be prescribed in 97% of NICU patients [52]. Although these results stem from a small study sample of 173 patients [52], and the methodological limitations of an observational study, they call for research that can provide a high-quality evidence to guide future analgosedation practices in the NICU. We aim to fill the current paucity in the literature as it pertains to a unique patient population. We believe our outcomes will be finally generalizable to a patient population that has been traditionally excluded from studies and guidelines [20, 48]. The dissemination of our objective review will be imperative to enhance clinical practice and evaluate the different components of the ABCDEF bundle, and hopefully to quantify the impact of bundle implementation to the various outcomes we have described. Some bundle components have been shown to have an economic benefit [61], and as researchers contribute to the collective growing body of knowledge, we anticipate that changes in practice will soon become the standard of care.

Abbreviations

- ABCDEF:

-

Assessing, preventing, and managing pain; Both spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; assessment, prevention, and management of Delirium; Early mobility and exercise; Family engagement and empowerment

- ICP:

-

IntraCranial pressure

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- JCAHO:

-

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations

- NICU:

-

Neurointensive care unit

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Barnes-Daly MA, Phillips G, Ely EW. Improving hospital survival and reducing brain dysfunction at seven California Community Hospitals: implementing PAD guidelines via the ABCDEF bundle in 6,064 patients. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:171–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002149.

Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Mechanical ventilation: lessons from the ARDSNet trial. Respir Res. 2000;1:73–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/rr15.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005043421801.

Shehabi Y, Bellomo R, Mehta S, Riker R, Takala J. Intensive care sedation: the past, present and the future. Crit Care. 2013;17:322. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12679.

Shehabi Y, Bellomo R, Reade MC, Bailey M, Bass F, Howe B, et al. Early intensive care sedation predicts long-term mortality in ventilated critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:724–31. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201203-0522OC.

Girard TD, Dittus RS, Ely EW. Critical illness brain injury. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:497–513. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-050913-015722.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1301372.

Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33:225–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2016.12.005.

Teitelbaum JS, Ayoub O, Skrobik Y. A critical appraisal of sedation, analgesia and delirium in neurocritical care. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:815–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100012385.

Payen J-F, Bosson J-L, Chanques G, Mantz J, Labarere J, DOLOREA Investigators. Pain assessment is associated with decreased duration of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a post Hoc analysis of the DOLOREA study. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1308–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c0d4f0.

Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E, Violet S, Sebbane M, Perrigault P-F, et al. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1691–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000218416.62457.56.

Olkowski BF, Shah SO. Early mobilization in the Neuro-ICU: how far can we go? Neurocrit Care. 2017;27:141–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-016-0338-7.

Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: Science and Philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:321–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002175.

Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7.

DAS-Taskforce 2015, Baron R, Binder A, Biniek R, Braune S, Buerkle H, et al. Evidence and consensus based guideline for the management of delirium, analgesia, and sedation in intensive care medicine. Revision 2015 (DAS-Guideline 2015) - short version. Ger Med Sci. 2015;13:Doc19. https://doi.org/10.3205/000223.

Tasker RC, Menon DK. Critical Care and the Brain. JAMA. 2016;315:749–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0701.

Vila H Jr, Smith RA, Augustyniak MJ, Nagi PA, Soto RG, Ross TW, et al. The efficacy and safety of pain management before and after implementation of hospital-wide pain management standards: is patient safety compromised by treatment based solely on numerical pain ratings? Anesth Analg. 2005;101:474–80, table of contents. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000155970.45321.A8.

Makii JM, Mirski MA, Lewin JJ. Sedation and analgesia in critically ill neurologic patients. J Pharm Pract. 2010;23:455–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190010372339.

Baker DW. History of the Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: lessons for today’s prescription opioid epidemic. JAMA. 2017;317:1117–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.0935.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:263–306. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72.

Chanques G, Conseil M, Roger C, Constantin J-M, Prades A, Carr J, et al. Immediate interruption of sedation compared with usual sedation care in critically ill postoperative patients (SOS-Ventilation): a randomised, parallel-group clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:795–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30304-1.

Esteban A, Frutos F, Tobin MJ, Alía I, Solsona JF, Valverdú I, et al. A comparison of four methods of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:345–50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199502093320601.

Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, Burke HL, Smith AC, Kelly PT, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1864–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199612193352502.

Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005183422002.

Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JWW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (awakening and breathing controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1.

Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:2644–53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.22.2644.

Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012;307:1151–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.304.

Shehabi Y, Riker RR, Bokesch PM, Wisemandle W, Shintani A, Ely EW, et al. Delirium duration and mortality in lightly sedated, mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2311–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f85759.

Strom T, Martinussen T, Toft P. A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;375:475–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62072-9.

Reade MC, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Bersten A, Cheung B, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine added to standard care on ventilator-free time in patients with agitated delirium: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1460–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2707.

Su X, Meng Z-T, Wu X-H, Cui F, Li H-L, Wang D-X, et al. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1893–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30580-3.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286:2703–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.21.2703.

Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Hui SL, Campbell NL, Farber MO, et al. The confusion assessment method for the ICU-7 delirium severity scale: a novel delirium severity instrument for use in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:851–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002368.

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.14.1753.

Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JWW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289:2983–91. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.22.2983.

Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, Balas MC, Ely EW, van der Voort PHJ, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9.

Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9.

Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1377–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3.

Study Investigators - Critical Care T. Early mobilization and recovery in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: a bi-national, multi-centre, prospective cohort study. 2015 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0765-4.

Engel HJ, Needham DM, Morris PE, Gropper MA. ICU early mobilization: from recommendation to implementation at three medical centers. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 Suppl 1):S69–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a240d5.

Hodgson CL, Berney S, Harrold M, Saxena M, Bellomo R. Clinical review: early patient mobilization in the ICU. Crit Care. 2013;17:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11820.

Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, Dugan DO, Blustein J, Cranford R, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.9.1166.

Burns KEA, Devlin JW, Patient HNS. Family engagement in designing and implementing a weaning trial: a novel research paradigm in critical care. Chest. 2017;152:707–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.028.

Haines KJ, Kelly P, Fitzgerald P, Skinner EH, Iwashyna TJ. The untapped potential of patient and family engagement in the organization of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:899–906. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002282.

Ren X-L, Li J-H, Peng C, Chen H, Wang H-X, Wei X-L, et al. Effects of ABCDE bundle on hemodynamics in patients on mechanical ventilation. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:4650–6. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.902872.

Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, Myatra SN, Salluh JIF, Amare D, et al. Worldwide survey of the “assessing pain, both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, choice of drugs, delirium monitoring/management, early exercise/mobility, and family empowerment” (ABCDEF) bundle. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e1111–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002640.

Society of Critical Care Medicine. Critical care statistics. https://www.sccm.org/Communications/Critical-Care-Statistics. Accessed 4 June 2018.

Oddo M, Crippa IA, Mehta S, Menon D, Payen J-F, Taccone FS, et al. Optimizing sedation in patients with acute brain injury. Crit Care. 2016;20:128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1294-5.

Lele A, Souter M. Sedation practices in the Neurocritical Care Unit. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2348-0548.174743.

Dunn LK, Naik BI, Nemergut EC, Durieux ME. Post-craniotomy pain management: beyond opioids. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-016-0693-y.

Costello TG, Cormack JR. Anaesthesia for awake craniotomy: a modern approach. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:16–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2003.09.003.

Zeiler FA, AlSubaie F, Zeiler K, Bernard F, Skrobik Y. Analgesia in neurocritical care: an international survey and practice audit. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:973–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001602.

Costa DK, White MR, Ginier E, Manojlovich M, Govindan S, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Identifying barriers to delivering the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium, and early exercise/mobility bundle to minimize adverse outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review. Chest. 2017;152:304–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.054.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. https://market.android.com/details?id=book-NKMg9sMM6GUC. Accessed 1 Oct 2018.

Navarese EP, Koziński M, Pafundi T, Andreotti F, Buffon A, Servi SD, et al. Practical and updated guidelines on performing meta-analyses of non-randomized studies in interventional cardiology. Cardiol J. 2011;18:3–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21305479.

da Silva PSL, Reis ME, Aguiar VE, Fonseca MCM. Unplanned extubation in the neonatal ICU: a systematic review, critical appraisal, and evidence-based recommendations. Respir Care. 2013;58:1237–45. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02164.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: what is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE.

Watts CR, Kelley P. Sedation and analgesia in neurosurgery/neurocritical care. Contemporary Neurosurgery. 2016;38:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.cne.0000502657.11174.29.

Hester JM, Guin PR, Danek GD, Thomas JR, Titsworth WL, Reed RK, et al. The economic and clinical impact of sustained use of a progressive mobility program in a neuro-ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1037–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002305.

Funding

The authors self-funded the preparation and publication of this manuscript. No external funding was received.

Author’s contributions

ME, BD, and DW conceived the research question and designed the review protocol. ME and BD completed the initial search and developed an electronic search strategy. ME consulted with a librarian at Thomas Jefferson University to further develop the search strategy. ME and BD pilot tested the data extraction forms. BD developed the direct and multiple comparison statistical analysis plan. DW, AN, and AL contributed equally to writing and revision of the manuscript. DW is the guarantor of the review protocol. The final version of the protocol submitted to BMC Systematic Reviews has been read and approved by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Dr. David Wyler is an Assistant Professor at the Departments of Anesthesiology and Neurological Surgery Division of Critical Care at Thomas Jefferson University, and the Director of Anesthesiology in Neurocritical Care at Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals and Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience. Dr. Michael Esterlis is an Anesthesiology Resident Physician at the University of Toronto. Dr. Brittany Burns Dennis is an MBBS candidate at University of London (St George’s); she received her PhD in Health Research Methodology from the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at McMaster University. Dr. Andrew Ng is a Clinical Assistant Professor at the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Abhijit Lele is an Associate Professor at the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Neurosurgery and Director of Neurocritical Care Services at Harborview Medical Center.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wyler, D., Esterlis, M., Dennis, B.B. et al. Challenges of pain management in neurologically injured patients: systematic review protocol of analgesia and sedation strategies for early recovery from neurointensive care. Syst Rev 7, 104 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0756-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0756-z