Abstract

Background

The correct perioperative management of antiplatelet therapy (APT) in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (NCS) is often debated by clinicians. American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend postponing elective NCS at least 3 months after stent implantation. Regardless of the timing of surgery, ACC/AHA guidelines recommend continuing at least ASA throughout the perioperative period and ideally continuing dual APT (DAPT) therapy “unless surgery demands discontinuation.” The objective of this review was to ascertain the risks and benefits of APT in the perioperative period, to assess how these risks and benefits vary by APT management, and the significance of length of time since stent implantation before operative intervention.

Methods

PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched from inception through October 2017. Articles were included if patients were post PCI with stent placement (bare metal [BMS] or drug eluting [DES]), underwent elective NCS, and had rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) or bleeding events associated with pre and perioperative APT therapy.

Results

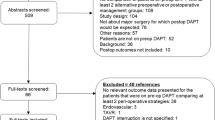

Of 4882 screened articles, we included 16 studies in the review (1 randomized controlled trial and 15 observational studies). Studies were small (< 50: n = 5, 51–150: n = 5, >150: n = 6). All studies included DES with 7 of 16 also including BMS. Average time from stent to NCS was variable (< 6 months: n = 3, 6–12 months: n = 1, > 12 months: n = 6). At least six different APT strategies were described. Six studies further utilized bridging protocols using three different pharmacologic agents. Studies typically included multiple surgical fields with varying degrees of invasiveness. Across all APT strategies, rates of MACE/bleeding ranged from 0 to 21% and 0 to 22%. There was no visible trend in MACE/bleeding rates within a given APT strategy. Stratifying the articles by type of surgery, timing of discontinuation of APT therapy, bridging vs. no bridging, and time since stent placement did not help explain the heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Evidence regarding perioperative APT management in patients with cardiac stents undergoing NCS is insufficient to guide practice. Other clinical factors may have a greater impact than perioperative APT management on MACE and bleeding events.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016036607

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Surgeons, cardiologists, primary care providers, and anesthesiologists frequently make decisions regarding the management of antiplatelet therapy (APT) for patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery (NCS). Patients with recent coronary stent implantation are challenging as clinicians balance the cardiac risks of discontinuing therapy with the bleeding risks of continuing antiplatelet agents.

Observational evidence suggests that patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are at increased risk of perioperative cardiac events. This risk is probably moderated by stent type, operative urgency, early discontinuation of APT, and time from coronary intervention [1,2,3,4]. American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend delaying NCS until 30 days after bare metal stent (BMS) placement and ideally 6 months after drug eluting stent (DES) placement [5].

The role of APT in mitigating this risk is unclear. ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that patients receiving dual APT (DAPT, typically aspirin [ASA] and a P2Y12 inhibitor) undergoing elective surgery should continue ASA through the perioperative period and restart the P2Y12 inhibitor as soon as possible. However, the level of evidence is cited as expert opinion. Bridging therapy—the act of discontinuing oral antiplatelet agents and substituting short-acting anticoagulants or intravenous antiplatelet agents—is sometimes considered in lieu of holding APT in its entirety. Despite ACC/AHA guidelines finding no evidence to support this strategy, a 2011 survey indicated that as many as half of interventional cardiologists endorse it [6].

To guide clinicians on this daily clinical scenario, we conducted a systematic review to determine if there is sufficient literature to make evidence-based recommendations about the management of APT in patients with coronary stents undergoing elective NCS.

Methods

This manuscript is a condensed and updated version of a report prepared for the Veterans Affairs (VA) that is free and publically available [7]. This review is reported according to PRISMA standards (Additional file 1) [8]. The key questions for this review were the following: (1) What are the risks and benefits of APT in the perioperative period after PCI? (2) Do the risks and benefits vary by timing of discontinuation and resumption of APT? and (3) Do the risks and benefits vary by type of procedure or by type of APT?

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus for English-language articles published before October 11, 2017. The search included terms for APT, PCI, and discontinuing therapy (Additional file 2). Three key references [3, 9, 10] were used to search for additional articles. We further explored the references of included studies.

All stages of review were conducted by two or more team members working independently. After initial title and abstract screen, full-text articles presenting original data were included based on the following PICOT criteria:

-

(1)

Patients were status post PCI with stent placement, on APT, undergoing elective NCS. Studies that combined cardiac and non-cardiac surgery were excluded unless outcomes were sufficiently stratified, or the proportion of cardiac surgery was small (< 10%). Surgery was broadly defined and included major and minor procedures as well as endoscopy.

-

(2)

Interventions considered included any combination of preoperative and perioperative APT management, including bridging. Preoperative strategies included DAPT or single APT (ASA, P2Y12). For each preoperative strategy, multiple permutations of perioperative management were considered such as DAPT, continue both agents; DAPT, hold one agent; or DAPT, hold both agents. Bridging strategies were also considered.

-

(3)

Comparisons included alternative APT or bridging strategies, as well as stratification by time from PCI, type of surgical procedure, and by drug.

-

(4)

Outcomes included bleeding and/or major adverse cardiac events (MACE) either as a composite or independently (i.e., in-stent thrombosis rates).

-

(5)

There was no restriction on timing.

Case series with less than 10 patients and studies evaluating coronary stents not available in the USA were excluded.

Data extraction was completed in duplicate with discrepancies resolved by the entire team. The following descriptive data were extracted: sample size, mean age of patients, percent of female patients, surgical procedure category, setting, country, number of centers, stent types, preoperative and perioperative APT management, length of APT cessation, and details of bridging therapy. When preoperative and perioperative APT strategies were unclear, attempts were made to contact the corresponding authors for clarification.

The quality of randomized trials was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias [11]. The quality of cohort studies was evaluated using items adapted from Hayden et al. [12], based on design (retrospective versus prospective), representativeness of the enrolled subjects, balancing for sampling differences, follow-up rates, and statistical methods. The overall quality of evidence was categorized based on the GRADE working group [13].

Outcomes assessed included MACE and bleeding events. We attempted to extract MACE and/or bleeding rates for each combination of pre- and perioperative APT (e.g., DAPT, hold both). MACE were typically defined as death, stent thrombosis, or myocardial infarction. If a study reported only one of these outcomes (i.e., stent thrombosis), we included it under the broader term “MACE.” Hemorrhagic outcomes were heterogeneous. We included clinically significant bleeding events as decided by consensus of surgeon members of the study team (CC, MMG, JU, IM). Definitions of bleeding for each study were extracted and are included in the data tables. Examples of clinically relevant bleeding included need for blood transfusion, re-operation, or escalation of care. Some studies used standardized criteria, such as Bleeding Academic Research Consortia (BARC) [14], but no two studies used the same criteria. Minor bleeding events (i.e., wound hematomas) were not included. We also collected the follow-up period for these outcomes.

Data were too heterogeneous for statistical pooling. Further, most studies only described one APT strategy without a comparison group. Of the studies that did compare two or more strategies, none compared the same two strategies. We were therefore unable to graph outcome rates in the traditional fashion (forest plots) but instead elected to plot MACE and bleeding outcomes stratified by pre- and perioperative APT management. This allowed visual assessment of the relationship between multiple APT strategies and event rates. Studies were further stratified across multiple variables including bridging, timing of APT discontinuation, surgical procedure (major versus minor), and duration of time between stent placement and surgery.

Results

Description of the studies identified by the literature search

The literature search identified 4882 possible citations; 123 articles were selected for full-text review, of which 16 studies were included in the analysis (Additional file 3). One study was a randomized trial. The remaining 15 were observational studies including two prospective cohort studies, 11 retrospective cohort studies, and two case-control studies. The included RCT did not blind participants/personnel and had unclear allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment (Table 1). The quality of cohort studies was variable; while most studies included a representative sample and abstracted data from medical records, methods used for assessing and adjusting differences in clinical variables were very heterogeneous (Table 2).

Studies were mostly small, with five including less than 50 patients, five with 51–150 patients, and six reporting over 150 patients. Tables 3 and 4 provide full details of the included studies. The mean age was greater than 60 years old for all studies and included predominantly male patients. All studies included patients with DES, and seven of the 16 studies included patients with BMS. All of the studies were conducted at academic or Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, and 12 of the 16 studies were conducted at single sites.

Within the study by Hawn et al., there were two distinct analyses relevant to our question. The first was a retrospective cohort of 41,989 VA patients who underwent NCS within 24 months of stent placement. The second was a case-control design of 284 patients with confirmed MACE, comparing to controls without MACE, looking specifically at APT management. A second case-control study was included that evaluated MACE and bleeding events in patients undergoing gastroscopy following DES placement. This study utilized two nested-case controls to evaluate cases (bleeding, MACE) compared to matched controls, focusing on the effect of APT management [15].

Antiplatelet and bridging strategies

Each study included one or more APT strategy, with or without bridging. For two studies [16, 17], we were unable to determine preoperative APT. Details of these two are included in the tables but are not in the figures or our analysis. Similarly, the case-control studies did not have event rates [1, 15]. We therefore had 12 studies with both pre and perioperative APT strategies with sufficient data to calculate outcome rates. Because studies could describe more than one strategy, there was a total of 17 MACE data points and 17 bleeding data points. Preoperative APT management included DAPT (usually clopidogrel and ASA), single APT (SAPT, usually ASA), or no APT. Five of the 10 studies grouped patients on preoperative DAPT and SAPT together. For each preoperative APT, there were multiple permutations of continuing or holding one or more therapies in the perioperative period. Further, six of the 12 studies also included bridging strategies. In sum, we describe six pre-perioperative APT strategies: DAPT, continue both (n = 3); DAPT, continue one (n = 1); DAPT, stop both (n = 2); DAPT or SAPT, stop all (n = 2); DAPT or SAPT, continue all (n = 2), DAPT or SAPT, continue clopidogrel only (n = 1). Bridging studies (n = 6) are discussed separately in this review.

Outcomes from a randomized trial

We identified one RCT that met most of our inclusion criteria [18]. This study of NCS in a USA academic setting randomized patients to continue or stop perioperative clopidogrel. Aiming for an enrollment of 3142 patients, the studied approached 4000 individuals. Only 48 were eligible and randomized, with 39 patients successfully completing the protocol undergoing 43 procedures. Only 72% of patients completing the study were post-PCI with stent placement. No data were available on type of stent or time since deployment. Seventy-four percent of patients were on DAPT preoperatively compared to 26% on clopidogrel only. There were no MACE in either group, and there was one bleeding-related re-hospitalization in each group with a follow-up of 90 days.

Outcomes related to antiplatelet strategy

Given the limitations of the one RCT, we broadened our review to include available observational evidence. MACE and bleeding rates ranged from 0 to 21% and 0 to 22% across studies, regardless of APT or bridging strategy. Among non-bridging studies, there was no association between APT strategy and outcome (Fig. 1). For example, four studies reported 0% MACE rates across three different APT strategies. Further, among the studies that used DAPT preoperatively, the study with the highest MACE event rate (21.4%) continued SAPT whereas the studies that stopped both agents had less than half the MACE rates (11.1% and 2.3%). For bleeding, three studies reported 0% rates representing three different APT strategies. The highest rate (14.8%) was reported in a study where both agents were stopped perioperatively. The case-control component of Hawn et al. found no difference in the odds of MACE across nine different APT strategies. The gastroscopy case-control study found higher odds of MACE in patients who held all APT therapy compared to patients who continued DAPT, however, this finding was not statistically significant (OR 3.46, CI 0.49–24.71). Further, the gastroscopy case-control study focused on bleeding found no re-bleeding events, and therefore no association with APT strategy.

Perioperative bridging strategies

Six of the studies described perioperative bridging strategies. No two studies used the same strategy. Bridging agents included glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors [19,20,21], low molecular weight heparin [20, 22], and unfractionated heparin [23, 24]. APT management varied within the bridging studies: some included just DAPT while others included DAPT or SAPT. Studies also varied in perioperative management of APT with some holding only the P2Y12 inhibitor, while others held both the P2Y12 inhibitor and ASA. Further, timing of discontinuation of APT, length of bridge, and need for preoperative hospitalization were different between these studies. For the bridging studies, MACE rates ranged from 0 to 7.8% and bleeding from 0 to 22% (Fig. 2).

Timing of discontinuation of antiplatelet agents

The timing of discontinuation of APT cessation varied between studies and among individual patients within studies. Most studies in which APT was discontinued preoperatively reported either a median or range of days of preoperative discontinuation. For the majority of these studies, APT agents were discontinued between 3 and 10 days preoperatively. No study systematically assessed the impact of timing of APT cessation on clinical outcomes. Postoperative management of APT was either not described, highly heterogeneous, or up to the discretion of the provider (Tables 3 and 4).

Time between stent implantation and surgery

Ten studies provided a measure of average time from PCI to NCS. Three studies averaged less than 6 months (“early”) [15, 21, 25], one was six to 12 months (“mid”) [26], and six were greater than 12 months (“late”) [16, 17, 19, 23, 24, 27]. Seven of these studies had outcomes associated with pre and perioperative APT strategies providing nine MACE data points and eight bleeding data points (Fig. 3). Measures of dispersion (standard deviations, interquartile regions) were large, such that a significant fraction of the cases may have crossed time categories. Further, APT management strategies and the use of bridging varied within each time category. MACE rates for the early group were 0–11%, for the mid group 0–2.3%, and the late group 0–7.8% (Fig. 3). The retrospective cohort component of Hawn et al. found that the risk of MACE declined with increasing time since stent placement, with a rate of 11.6% for those < 6 weeks, 6.4% for those 6 weeks to 6 months, 4.2% for 6 months to 1 year, and 3.5% for 1 year to 2 years.

Type of surgery

Most studies included a mix of surgical procedures, both major and minor, across surgical disciplines. Studies did not provide enough detail to assess outcomes for a given surgical specialty, let alone individual procedures. Two studies [23, 28] addressed only thoracic surgery. However, the studies had small samples (21 and 38 patients) and different APT management strategies. One included bridging and the other did not. MACE rates were 0 and 5%, and bleeding rates were 0 and 9.5%. The retrospective cohort component of Hawn et al. identified type of surgery as a predictor of MACE, with respiratory, vascular, and digestive operations carrying significantly higher risk (10.6, 8.4, and 8.1%, respectively) than eye/ear and integumentary operations (1.7 and 3.0%, respectively).

Grading the quality of evidence

We judged the overall quality of evidence as very low, based on serious limitations in study design, consistency of results, and precision of the estimates.

Discussion

The principle conclusion from our systematic review is that the available literature is insufficient to guide perioperative APT management in patients with coronary stents undergoing NCS. Further, the results suggest that clinical factors other than APT management may be more responsible for MACE and bleeding rates such as indication and urgency of operation, timing since stent placement, invasiveness of the procedure, preoperative cardiac optimization, and functional status.

Our results do not imply that APT management is inconsequential. There are a number of reasons to believe that APT management has a causal role in MACE and bleeding rates. Aspirin selectively inhibits cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 resulting in irreversible inhibition of the platelet activator thromboxane A2, while P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidogrel, prasurgrel, ticagrelor) inhibit P2Y12 ADP receptors—both mechanisms ultimately reducing platelet activation [29]. However, current available evidence is insufficient to conclude these physiologic rationales translate into appreciable differences in MACE and bleeding outcome rates dependent on perioperative APT management strategies.

The 2014 guidelines from the AHA/ACA recommended delaying elective NCS for 1 year after DES and 30 days after BMS placement. In patients undergoing urgent NCS, they recommended continuing DAPT therapy for 4–6 weeks unless the risks of bleeding outweigh the risks of stent thrombosis [30]. The 2016 update modified the former of these recommendations by reducing the window from 1 year to 6 months and also considering operations after 3 months if the risk of delaying surgery is greater than the risk of stent thrombosis [5]. These recommendations were based on contemporary evidence suggesting reduced risk of stent thrombosis with newer generation DES and on the study from Hawn et al.

The two components of Hawn et al. included a retrospective review of over 40,000 patients undergoing NCS after stent implantation as well as a case-control subset of cases (those with MACE) versus controls to ascertain the role of APT strategies in MACE outcomes. Multivariate analysis of the first component showed that non-elective surgery, recent myocardial infarction, elevated cardiac risk index, the presence of heart failure, age, the presence of chronic kidney disease, and type of operation were all associated with increased MACE risk. They further showed a sharp decline in MACE rates from time since stent implantation with an asymptote at approximately 6 months. Their case control subset looked at nine different APT strategies with no difference in the odds of MACE. The 2016 update to ACC/AHA guidelines repeat the 2014 recommendations regarding APT management encouraging providers to continue ASA through the perioperative period, and if previously on DAPT, to restart the P2Y12 inhibitor shortly after surgery. The result of the studies included in our review, and specifically that of Hawn et al., suggest that the importance of APT agent is likely small compared to other clinical factors.

This systematic review is limited primarily by the quality and quantity of the available evidence. Only one RCT evaluated the management of APT in patients undergoing NCS, but this study was very small (< 40 patients) and included almost 30% of patients without a history of coronary stent (not our main population of interest). Observational studies in this space are insufficient to make up for the paucity of randomized evidence. Many of the included observational studies lacked a control group rendering comparisons impossible. The few studies that did include a control group did not address sample imbalances. Case control studies are not directly comparable to cohort studies as they do not provide actual event rates. Further, patients within and across studies were heterogeneous along multiple domains including time since stent implantation, indication for procedure, and type of surgery. APT management within a given study was similarly heterogeneous using multiple APT strategies, inconsistent timing of discontinuation and restarting therapy, as well as the use of bridging.

Given the likelihood of confounding, observational studies will have difficulty in identifying or balancing these factors rendering further observational studies of the types identified in this review of little utility. Randomized studies would address this concern but inherently struggle with other limitations—namely sample size. The one RCT addressing our question enrolled only 39 patients. To detect a reduction in MACE from 5% to 3% would require a sample of approximately 1500 patients in each arm. Any further stratification, such as looking at different types of surgical procedure, or including more than one APT strategy, would require increasing this sample size further. While challenging, a sufficiently powered RCT should remain the goal. RCTs evaluating patients with cardiac disease are often capable of enrolling many thousands of patients suggesting that a study of perioperative APT management is feasible.

Conclusions

Published studies of the association between perioperative APT management and outcomes in patients with coronary stents undergoing NCS have challenging methodologic limitations and heterogeneous results. The results suggest that clinical factors other than perioperative APT management may be more responsible for MACE and bleeding outcomes. A large clinical trial or exceptional observational study will be needed to definitively provide evidence about this clinical decision. We conclude that there is insufficient evidence to guide perioperative APT management in patients with coronary stents undergoing NCS. For now, the decision must be tailored to the situation, guided by a collaborative approach between the surgeon, cardiologist, anesthesiologist, and the patient.

Abbreviations

- ACC/AHA:

-

American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association

- APT:

-

Antiplatelet therapy

- ASA:

-

Aspirin

- BMS:

-

Bare metal stent

- DAPT:

-

Dual antiplatelet therapy

- DES:

-

Drug eluting stent

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiac event

- NCS:

-

Non-cardiac surgery

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- SAPT:

-

Single antiplatelet therapy

- VA:

-

Veterans Affairs

References

Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. JAMA. 2013;310:1462–72.

Kaluza GL, Joseph J, Lee JR, Raizner ME, Raizner AE. Catastrophic outcomes of noncardiac surgery soon after coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1288–94.

van Kuijk JP, Flu WJ, Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Schenkeveld L, de Jaegere PP, Bax JJ, van Domburg RT, Serruys PW, Poldermans D. Timing of noncardiac surgery after coronary artery stenting with bare metal or drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1229–34.

Wilson SH, Fasseas P, Orford JL, Lennon RJ, Horlocker T, Charnoff NE, Melby S, Berger PB. Clinical outcome of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the two months following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:234–40.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, Granger CB, Lange RA, Mack MJ, Mauri L, et al. ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;2016(152):1243–75.

Khair T, Garcia B, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Contemporary approaches to perioperative management of coronary stents and to preoperative coronary revascularization: a survey of 374 interventional cardiologists. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2011;12:99–104.

Maggard Gibbons M, Ulloa JG, Macqueen I, Childers CP, Miake-Lye IM, Shanman R, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG. Management of Antiplatelet Therapy among Patients on Antiplatelet Therapy for Coronary or Cerebrovascular Disease or with Prior Percutaneous Cardiac Interventions Undergoing Elective Surgery: A Systematic Review. VA ESP Project #05- 226; 201.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Albaladejo P, Marret E, Samama CM, Collet JP, Abhay K, Loutrel O, Charbonneau H, Jaber S, Thoret S, Bosson JL, Piriou V. Non-cardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents: the RECO study. Heart. 2011;97:1566–72.

Singla S, Sachdeva R, Uretsky BF. The risk of adverse cardiac and bleeding events following noncardiac surgery relative to antiplatelet therapy in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2005–16.

JPT H, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from http://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280–6.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Group GW. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6.

Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–47.

Egholm G, Thim T, Madsen M, Sorensen HT, Pedersen JB, Eggert Jensen S, Jensen LO, Kristensen SD, Botker HE, Maeng M. Gastroscopy-related adverse cardiac events and bleeding complications among patients treated with coronary stents and dual antiplatelet therapy. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E527–33.

Assali A, Vaknin-Assa H, Lev E, Bental T, Ben-Dor I, Teplitsky I, Brosh D, Fuchs S, Eidelman L, Battler A, Kornowski R. The risk of cardiac complications following noncardiac surgery in patients with drug eluting stents implanted at least six months before surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74:837–43.

Bolad IA, Alqaqa'a A, Khan B, Srivastav SK, von der Lohe E, Sadanandan S, Breall JA. Cardiac events after non-cardiac surgery in patients with previous coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011;23:283–6.

Chu EW, Chernoguz A, Divino CM. The evaluation of clopidogrel use in perioperative general surgery patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg. 2016;211:1019–25.

Alshawabkeh LI, Prasad A, Lenkovsky F, Makary LF, Kandil ES, Weideman RA, Kelly KC, Rangan BV, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Outcomes of a preoperative “bridging” strategy with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors to prevent perioperative stent thrombosis in patients with drug-eluting stents who undergo surgery necessitating interruption of thienopyridine administration. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:204–11.

Conroy M, Bolsin SN, Black SA, Orford N. Perioperative complications in patients with drug-eluting stents: a three-year audit at Geelong Hospital. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:939–44.

Marcos EG, Da Fonseca AC, Hofma SH. Bridging therapy for early surgery in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:412–7.

Capodanno D, Musumeci G, Lettieri C, Limbruno U, Senni M, Guagliumi G, Valsecchi O, Angiolillo DJ, Rossini R. Impact of bridging with perioperative low-molecular-weight heparin on cardiac and bleeding outcomes of stented patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:423–31.

Sonobe M, Sato T, Chen F, Fujinaga T, Shoji T, Sakai H, Miyahara R, Bando T, Huang CL, Date H. Management of patients with coronary stents in elective thoracic surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:477–82.

Tanaka A, Ishii H, Tatami Y, Shibata Y, Osugi N, Ota T, Kawamura Y, Suzuki S, Nagao Y, Matsushita T, Murohara T. Unfractionated heparin during the interruption of antiplatelet therapy for non-cardiac surgery after drug-eluting stent implantation. Intern Med. 2016;55:333–7.

Choi CU, Rha SW, Jin Z, Chen KY, Minami Y, Kim JH, Na JO, Suh SY, Kim JW, Kim EJ, et al. The optimal timing for non-cardiac surgery after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:313–6.

Brotman DJ, Bakhru M, Saber W, Aneja A, Bhatt DL, Tillan-Martinez K, Jaffer AK. Discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy prior to low-risk noncardiac surgery in patients with drug-eluting stents: a retrospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:378–84.

Tanaka A, Sakakibara M, Ishii H, Okumura S, Suzuki S, Inoue Y, Jinno Y, Okada K, Murohara T. The risk of adverse cardiac events following minor surgery under discontinuation of all antiplatelet therapy in patients with prior drug-eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:e125–6.

Cerfolio RJ, Minnich DJ, Bryant AS. General thoracic surgery is safe in patients taking clopidogrel (Plavix). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:970–6.

Mega JL, Simon T. Pharmacology of antithrombotic drugs: an assessment of oral antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatments. Lancet. 2015;386:281–91.

Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, Barnason SA, Beckman JA, Bozkurt B, Davila-Roman VG, Gerhard-Herman MD, Holly TA, Kane GC, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;2014(64):e77–137.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Yamamoto K, Wada H, Sakakura K, Ikeda N, Yamada Y, Katayama T, Sugawara Y, Mitsuhashi T, Ako J, Momomura S. Cardiovascular and bleeding risk of non-cardiac surgery in patients on antiplatelet therapy. J Cardiol. 2014;64:334–8.

The GUSTO investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673–82.

Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, Borer J, Cohen LS, Dalen J, Dodge HT, Francis CK, Hillis D, Ludbrook P, et al. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial, phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76:142–54.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of our technical expert panel: Peter Glassman, Chester “Bernie” Good, John S. Lane, Lisa Longo, John Sum-Ping, and Arthur Wallace. None of these individuals were compensated in association with their contributions to this article.

Funding

The publication is based on a systematic review conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis program funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The full report is publically available online at: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/AntiplateletTherapy.cfm. The VA had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Drs. Childers and Shekelle had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All data used for this study are accessible for review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CPC was involved in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; drafting the manuscript; revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; and conducting statistical analysis.

MMG was involved in study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; drafting the manuscript; revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; conducting statistical analysis; and study supervision. JGU was involved in study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. ITM was involved in study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. IMM was involved in study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; and administrative, technical, and material support. RS was involved in administrative, technical, or material support. SM was involved in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and administrative, technical, and material support. JMB was involved in administrative, technical, and material support. PGS was involved in study conception and design; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtaining funding; and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was considered exempt by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Dr. Paul G. Shekelle is the editor-in-chief for BMC Systematic Reviews. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA Checklist. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search terms. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 3:

PRISMA Flow Diagram. (PDF 91 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Childers, C.P., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Ulloa, J.G. et al. Perioperative management of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery following coronary stent placement: a systematic review. Syst Rev 7, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0635-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0635-z