Abstract

Scientific communication is one of the most challenging aspects of volcanic risk management because the complexities and uncertainties of volcanic unrest make it difficult for scientists to provide information that is timely, relevant, easily comprehensible and trusted. When poorly handled, scientific communication can cause social, economic and political problems, and undermine community confidence in disaster management regimes.

This is the first of two related papers that together investigate the interface between the scientific consideration of volcanic hazards and the governance of volcanic risks. Both papers are principally concerned with issues of risk governance, and their focus is hazard communication by volcanologists at this hazard-risk interface (the interface) during periods of volcanic unrest. In this paper, we argue that the working practices of contextualisation must be more methodical and propose four quality assurance standards that will enhance hazard assessments.

To improve hazard communication between volcanologists and risk-mitigation decision-makers (decision-makers), we argue that volcanologists need to adopt a more iterative and structured approach that openly embraces the benefits, and confronts the challenges, of stakeholder-orientated ‘contextualisation’.

Our analysis of the published literature reveals evidence of a slow paradigm shift from practices based upon strict linear technocratic approaches to more iterative stakeholder participation. The extent of this shift varies in different regions, however, the rules and practices of deliberation often appear ad hoc and unstructured.

Since there is currently insufficient guidance for managing the practicalities and standards of contextualisation, we introduce two novel concepts; the ‘scrutiny dimension’ of risk governance, which is the slow changing governance context that may influence the processes of contextualisation, and the dynamic ‘equilibrium of contextualisation’, which is the metastable product of regulatory standards, natural and organisational constraints, and stakeholder pressures.

We argue that the working practices of contextualisation must be more structured and should strive to be open, transparent and fully articulated. Contextualisation, which meets proposed quality assurance standards of materiality, proximity, comprehensibility and integrity, will enhance hazard assessments and, thereby, the utility of their outputs. In our second paper (Bretton et al, J Appl. Volcanol. DOI 10.1186/s13617-018-0079-8, 2018), the focus is directed away from the perceived qualities of more ‘socially robust’ hazard assessments towards the actual process of contextualisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

This is the first of two related papersFootnote 1 that together investigate the interface between the scientific consideration of volcanic hazards and the governance of volcanic risks. Both papers are principally concerned with issues of risk governance, and their focus is hazard communication by volcanologists at this hazard-risk interface (the interface) during periods of volcanic unrest. In this paper, we argue that the working practices of contextualisation must be more structured and propose four quality assurance standards that will enhance hazard assessments. In our second paper, the focus is directed away from the perceived qualities of more ‘socially robust’ hazard assessments towards the actual process of contextualisation.

During periods of volcanic unrest, significant practical challenges of timing, relevance, comprehensibility and trust exist for volcanologists operating at the interface that was described by Jolly and Cronin (2014) as the “science-management interface”. Periods of unrest not only create uncertainty about what is happening in a physical sense but also increase demands for scientific analysis, information and advice (Johnston et al. 2002). Analysis of volcanic unrest often involves the characterisation of the physical, temporal and spatial parameters of future scenarios, with a typical analytical product being a hazard map. The overall objective is to answer foreseeable questions from decision-makers involved in risk mitigation. These questions will include multiple variations of ‘What’ (physical parameters of chemical composition, heat, size, flux, weight, speed, etc.), ‘When’ and ‘For how long’ (temporal parameters), and ‘Where’ (spatial parameters both horizontal and vertical).

Scientific communication is one of the most challenging aspects of volcanic risk management (Marti 2015) because it must address issues of both knowledge and ignorance (e.g. uncertainties, errors, absences of knowledge and other forms of non-knowledge). The issues involve: (1) aleatory uncertainty due to the inherent variability or randomness of volcanic hazards that often involve dynamic, complex and non-linear processesFootnote 2; (2) epistemic uncertainty due to constraints upon our understanding, our information (e.g. inadequate or uncertain data used to drive and evaluate models), and our resources (e.g. computing or time for reflection); (3) interpretative and deliberative human processes and subjective choicesFootnote 3; and (4) as a result of the first three, the foreseeable possibility of legitimate and responsible scientific disagreement such as was allegedly evident during the volcanic incidents in Guadeloupe (1976), St Vincent (1979) and Mount St Helens, Washington, USA (2004) (Fiske 1984; Driedger et al. 2008; Frenzen and Matarrese 2008).

When faced with scientific uncertainties and juggling societal and political pressures, decision-makers frequently request certainty, precision, accuracy and unambiguous consensus from their expert advisers (McGuire and Kilburn 1997; Paton et al. 1998, 1999, 2000; WBGU 2000; Aspinall 2011; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2012; Jolly and Cronin 2014). The implications of the preceding discussion, however, are that no representation of a volcanic hazard can be entirely certain, precise, complete, simple or objective. Furthermore, the stakes for at-risk communities are high, given that communications of scientific knowledge, when poorly handled, can cause social, economic and political problems, even if the identified hazards do not lead imminently to physical consequences such as an eruption (Johnston et al. 2002). There is thus a constant risk that community confidence in disaster management regimes could be undermined (Christie et al. 2015).

Contextualisation is the term used in this paper to describe the critical process of interactions between volcanologists and risk governance decision-makers and, specifically, the tailoring of hazard assessments to ensure they are driven by the needs of decision-makers. We start from the contention that effective contextualisation is achieved when volcanologists provide timely hazard assessments that are relevant, easily understood and trusted. Furthermore, our investigation of communication practicalities was conducted at an important moment – the immediate aftermath of the L’Aquila trial and during a period of evolving international law norms and disaster risk management initiatives. We hypothesise that the L’Aquila trial identified a failure of contextualisation within a risk governance process and we argue in this paper that volcanologists need to adopt an approach that openly embraces the benefits and confronts the challenges of contextualisation if they are to improve hazard communication at the interface.

Choices of terminology, theoretical models and assumptions

For the sake of brevity and clarity, we draw upon the existing rich discourse on relevant terminology and adopt the working definitions in Additional file 1.

We:

-

1.

Differentiate in both theory and practice between the overall governance of the risks associated with natural hazards (risk governance), and those parts of risk governance that require the services of volcanologists (hazard assessments).

-

2.

Do not seek to challenge the discourse that compares objective/innocent/science-right and constructivist/democratic/right-science approaches to risk governance (e.g. US/NRC 1996; Grabill and Simmons 1998) but argue that it is incomplete in several respects.

-

3.

Argue that, in the absence of readily accessible alternatives, many of the concepts and values that are currently framed principally in the context of risk governance can, and should be, used to enhance hazard assessments.

-

4.

Deliberately avoid use of the expression “end-users” to describe decision-makers receiving science-based services. Given that we argue in favour of the planned and integrated contextualisation of services throughout the cycle of their production and delivery (not just at the ‘end’ of a linear production process), we acknowledge the inadequacy of this misleading expression. Alternative expressions, such as “collaborators”, “co-producers” and “partners”, have other weaknesses.

-

5.

Assume that, in most countries, volcanologists do not normally lead risk governance efforts, but instead undertake hazard assessments and contribute hazard knowledge and, if requested, related advice.

-

6.

Accept the possibility of an unintended Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-USA and/or Western Hemisphere bias due to the authors’ limited knowledge of the legal frameworks operative in many volcanic regions of the world. Future investigations involving lawyers practising in, inter alia, Iceland, South-East Asia, Latin and South America, Africa, and Japan would provide helpful complementary research.

Distinct approaches to communication lie at the heart of competing theories of risk governance and, if we are to arrive at a reasoned and coherent approach, we must be clear about: (1) the respective roles of volcanologists and decision-makers within hazard assessments; (2) the factors driving the quality of associations between volcanologists and decision-makers; and (3) the likely sentiments (such as confidence and trust) and actions (such as risk-mitigation decisions) within those associations. Our choices in respect of the above have a direct effect on the way we address the underlying purposes and goals of the processes and outputs of volcanic hazard analysis and thus also on the way we address the design of those processesFootnote 4.

We adopt an holistic approach to risk governance, accepting that it involves the convergence of physical, societal and managerial dimensions (Cardona 2004). Acknowledgement of the existence of a managerial dimension encourages identification of decision-makers and what hazard and risk knowledge they need. To provide a coherent risk governance model that recognises the paramount importance of effective risk decision-making, we adopt a weak constructivist approach after accepting a positivist conception of risk and democratic approach to cultural bias. These terms are considered in greater detail in Additional file 2 and shown in italics whenever used.

In the absence of a positivist conception of risk, it would be difficult to justify the monitoring of volcanoes to produce hazard knowledge. The ambitious claim of risk is that ‘past’ parameters must be investigated because the past may enhance analyses of the present and forecasts of the future.

The word ‘weak’ is critical to the very basis upon which volcanic hazards are monitored and analysed. It is accepted that such hazards exist as objective physical phenomena capable of analysis. ‘Present' dynamic parameters can and should be monitored, analysed, quantified and communicated but, since we accept that risk is a social construction incorporating physical and societal dimensions, decision-makers’ perceptions and understandings are not only relevant but also critical because they are directly related to, and will influence, their sentiments and actions.

In using the constructivist actor-network approach, we appreciate that it is important to seek evidence of ‘associations’ and ‘effects’ (Callon 1986a, 1986b; Latour 1987, 1999a, 1999b; Law 1992, 1999). The effectiveness or value of a hazard communication is derived from, and is a consequence of, the actions and sentiments of its recipients – in other words - its “effects”. Consistent with the social constructivist choice that we have made, a democratic approach to cultural bias is adopted. This emphasis on the centrality of what we might call the reception of hazard communication implies that volcanologists are not entitled to claim an intrinsic status of privilege, dominance or superiority as may be assumed in technocratic and decisionist models of risk governance.

Communication is also central to the iterative non-linear approach that we favour for both hazard and risk knowledge production. Effective communication requires deliberative processes, and deliberation is in turn the precursor to, and the driver of, contextualisation. We reject both realistic approaches and conventional linear governance models that do not place communication centrally within every part of the governance process. A relativist approach is preferred by us because we accept that hazard knowledge: (1) can never be either entirely objective or value free; (2) can and should be influenced by societal contexts and managerial norms within openly discussed and agreed constraints; and (3) should be the decision-maker or “audience” (Leonard et al. 2014, 227) focussed product of iterative analytical-deliberative hazard assessments.

It is important to emphasise the link between contextualisation and relativist/interpretivist approaches to communication. Contextualisation (or ‘socialisation’), which demands communications that are interactional, situational, episodic and improvised (Pacanowsky and O’Donnell-Trujillo 1983), is one way in which the design of hazard assessments can be changed in order to influence their effects. Through the empirical study of effects, it is possible to measure the efficacy of the overall scientific contribution, and thus the strengths and weaknesses of the associations between volcanologists and decision-makers. Nonetheless, it is readily accepted that any measurement of effects may be very difficult in practice.

For the purposes of this paper, we argue that the discourse that compares objective/innocent/science-right and constructivist/interpretivist/democratic/right-science approaches to risk communication is incomplete in several ways. It pays insufficient regard to the status of the hazard element of risk – risk being the convolution of elements of hazard, exposure and vulnerability. Within the weak constructivist approach that we adopt, whilst overall risk may be a social construct and susceptible to negotiation using participatory processes (“a subject world”), the natural hazard element is a physical real-world phenomenon (“an object world”) requiring expert scientific assessments, albeit assessments requiring subjective choices (Birkmann et al. 2015, 236). In both theory and practiceFootnote 5, there is therefore a tension between the subjective/normative and objective/descriptive elements of risk (Longino 1993; Schwandt 2000Footnote 6) and, with reference to the terminology of the US/NRC (1996), there is room for conflict between the concepts of “getting the science right”, measured by standards of scientific adequacy, and “getting the right science”, which requires standards of utility.

We address the persistent failure by risk governance commentators to investigate methodically and holistically the challenges related to the production and communication of hazard knowledge, having focussed instead upon the negotiated construction and communication of risk, or a single feature of hazard communication such as ‘understandability’ or ‘trust’. Insufficient attention has been given to the drivers of the associations between volcanologists and decision-makers and the possible influence of regulatory and non-scientific pressures. The challenges, to which we refer, raise complex issues of ‘negotiation’, that are demonstrably real, quantifiable and potentially significant, and therefore should be mitigated.

Introducing the ‘scrutiny dimension’ of risk

Within social constructivist models the concept of risk has at least three overlapping functions. Risks, like hazards, are objects of governance which must be quantified to facilitate their integration for decision-making purposes. Secondly, risk is a methodology by which future volcanic uncertainties can be managed. Thirdly, the methodology of risk has a normative (i.e. ethical) dimension and definable norms, standards and expectations – in other words, quality standards that circumscribe, and direct the conduct appropriate for a given situation. These standards can also be used as tools to monitor performance and apportion blame. ‘Actual conduct’ (including quantifications of the parameters of hazard, exposure and vulnerability) can be measured against ‘right conduct’ in a situation in which a decision-maker must consider numerous possible actions and decide what should be done (IRGC 2009; Ben-Ari and Or-Chen 2009; Walker et al. 2010; Thompson 2012). It follows that risk is the mother of its unintended offspring, the scrutiny dimension that we now introduce.

We adopt and build upon the ‘physical’, ‘societal’ and ‘managerial’ dimensions of risk governance identified by Cardona (2004). The last of these, which includes “management capacity and related actors”, determines the need for, and the purpose and nature of, interactions between risk governance stakeholders (Cardona 2004, 47Footnote 7).

Specifically, we build on Cardona (2004) by noting there is slow changing context in which risk management takes place, which we refer to as the ‘scrutiny’ dimension. This novel fourth dimension of risk reflects the extent to which decision-makers and their decisions will be scrutinised and influenced by legal and other processes that seek to promote better governance with reference to standards set by, inter alia, international, national and local laws, as well as less formal initiatives and expectations. Laws create a framework of governance to order: (1) behaviour (converting governance policies into outcomes); (2) power (defining structures, duties and rights that distribute responsibilities and power between many stakeholders); and (3) contestation (providing substantive and procedural tools to promote responsibility and accountability and to resolve disputes) (Bretton et al. 2015, 2017; WBG 2017).

There are many potential scrutiny sources and they include those detailed in Table 1 that are entirely external to the stakeholders. Six potential sources of regulatory standards are discussed later in this paper and summarised in Table 5.

It is the scrutiny dimension that creates management challenges for decision-makers and may influence their associations with, and their demands upon, volcanologists. We adopt the working hypothesis that the requirements of decision-makers change over several different time-scales and that, by means of careful and effective dialogue, they can be identified. In the short-term, the demands may change during the many phases of a cycle of volcanic unrest. Over longer periods, they will change in response to actual and perceived changes in the scrutiny dimension.

Insufficient guidance exists for managing the practicalities and standards of contextualisation. We argue that the scrutiny dimension has the potential to be the main influence upon the demands of decision-makers and, thereby, the main agent behind changes to the metastable ‘equilibrium of contextualisation’, which we introduce later. This equilibrium explains the consequences of the absence of commonly recognised standards (norms) capable of guiding, measuring and evolving acceptable practice - standard equivocality - identified by Bretton et al. (2015).

Effective communication

There is a rich discourse in the field of volcanic risk governance that identifies many factors that drive the ‘effectiveness’ of communication (Leonard et al. 2014; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014; Doyle et al. 2015; Christie et al. 2015; Mothes et al. 2015; Scolobig et al. 2017; Preuner et al. 2017).

Based on this discourse, we accept as a working assumption that different stakeholders have distinct: (1) capacities; (2) understandings (mental models); and (3) needs and expectations. Effective communications reflect an appreciation of and, are driven by, these differences. Ineffective communication can lead to decision-makers making ill-informed decisions (US/NRC 1996; Solana et al. 2008) with associated direct and indirect consequences. Recent cases, including the L'Aquila case, have shown that legal consequences may flow from communication inadequacies (Lauta 2014a, 2014b; Bretton 2014, Bretton et al. 2015, 2017; Scolobig et al. 2014; Scolobig 2015; Doyle et al. 2015; Alexander 2014a, 2014b; Bretton and Aspinall 2017).

We have identified, and seek to integrate within our investigation of contextualisation, eight key factors that are summarised in Table 2.

These key factors show that communication is more likely to be effective if it is ‘tailored’ to the capacities and needs of its recipients and, accordingly: (1) is relevant to the risk-mitigation decisions that must be made; (2) is received easily and on time; and (3) can be understood and trusted. This tailoring, in other words contextualisation, is an obvious and inevitable response to the managerial dimension of risk governance. It is also evidence of a critical association between volcanologists and decision-makers. The nature and quality of that relationship, and the tailoring it fosters, need to be investigated carefully and are the principal focus of the next section.

Contextualisation

Using several sub-headings, this section presents and discusses our literature review of the theoretical basis, evolution and practical challenges of contextualisation. It also investigates several aspects of quality assurance.

Theoretical basis

Two extremes of knowledge production can be described and contrasted. Mode-1 products have been described as conventional scholarly reflections that are driven by the motivations of their producers “to get the science right” (US/NRC 1996). Detached from both social context, and political and other values, these products seek to characterise and predict the natural world ‘as it is’, for a separate, sequential, downstream political management response. If any degree of contextualisation is considered, it comes towards the end of a linear process after the completion of analysis, is limited to communication and does not entail an iterative process of deliberation involving science users.

Mode-1 science is universal, invariant and abstract. In this context, ‘abstract’ means detached from both social context, and political and other values. It is a product of a closed, isolated, innocent, politically dust-free and sterile environment (Weinberg 1972; Douglas 1992; Beck 1992; Ravetz 1999; Horlick-Jones 1998; Nowotny 2003; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006).

By contrast, Mode-2 products are driven by the requirements of their users. Their production and application are contextualised by co-evolutionary processes of reverse communication (i.e. open dialogue) between producers and users (Weinberg 1992; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006). Contextualisation involves not only changes of planned outputs and outcomes, but also changes of analytical emphasis and methodology, in other words production decisions (Blockley 1992; Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993; Nowotny 2003).

Evolution

Volcanic risk governance regimes are slowly changing and, perhaps surprisingly, the origins of change can be traced to dates before 1996, when the US/NRC criticised traditional linear models and advocated an analytic-deliberative approach. Since 1984, commentators upon volcanic hazards (including those listed in Additional file 3) have advocated with increasing frequency the merits of contextualising volcanic hazard assessments through processes of deliberation. There is evidence of a slow-moving, disorganised, yet perceptible, paradigm shift from those regimes narrowly based upon linear (i.e. non-deliberative) objectivist and decisionist governance models to more iterative constructivist initiatives that review the benefits and challenges of more stakeholder-focused deliberative processes. Additional file 3 contains a complete time-line of iterative initiatives and associated published literature.

Despite the paradigm shift noted above, advances in expert and academia-driven Mode-1 science have not been matched by corresponding improvements in communication practices that help decision-makers to make more informed risk-mitigation decisions and better use of risk-mitigation arrangements (IFRC 2015; Preuner et al. 2017; Scolobig et al. 2017). Critics of traditional linear models (including US/NRC 1996; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014; Preuner et al. 2017; Scolobig et al. 2017) have argued that those models:

-

1.

failed to address the questions that users see as relevant or to reflect the perspectives and concerns of risk management stakeholders (often described as including ‘public officials’, ‘interested and affected parties’, and ‘at-risk individuals’);

-

2.

communicated unhelpful scientific information to decision-makers leading them to make unwise decisions;

-

3.

confined scientific analysis to good characterisations of volcanic behaviour;

-

4.

failed to identify the need for, and/or inappropriately restricted, stakeholder participation; and

-

5.

“significantly oversimplified the process of volcanic risk management” (Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014, 152).

To address the perceived failings of the traditional linear models, many commentators (including those listed in Table 2), without using variations of the word ‘contextualised’, advocate scientific assessments of natural and volcanic hazards that encompass the characteristics listed in Table 3.

The paradigm shift towards more stakeholder-focused deliberative processes appears to be entirely consistent with our earlier summary of the current theoretical discourse about volcanic risk governance models. Furthermore, the momentum for change is increasing as evidenced by a higher number of published research sources addressing issues consistent with constructivist values and, in particular, those related to the democratic approach to cultural bias and the effectiveness of hazard communications.

In Additional file 3, we have identified papers confronting the challenges of participation, stakeholder-needs, contextualisation, comprehensibility, credibility and novel knowledge sources. Closer examination of the academic background of recently-published researchers reveals that: (1) transdisciplinary research projects are becoming more common (e.g. VUELCO; STREVA and DEVORAFootnote 8); and (2) by inference, research funders accept the relevance and significance of contributions made by social scientists (e.g. the European Union’s Framework programmes, NERC and ESRC).

Additional file 3 also demonstrates that the paradigm shift is patchy reflecting the reality that ‘paradigm-challenging’ research projects, with limited budgets, are often confined to small geographical areas and, for obvious reasons, are more common and/or better reported in affluent regions and countries (such as North America, Europe, former European dependencies, and New Zealand). We also acknowledge that, country-by-country, historical and cultural differences may result in different appetites for more democratic governance initiatives. In other words, not all countries with volcanic hazards currently embrace notions of democracy, freedom of information, and active stakeholder dialogue and participation to an equal extent.

Another lesson from the review is that there appears to be little or no readily accessible evidence of documented protocols for more iterative processes of volcanic risk governance. We have found no country that has laws and/or binding governance standards that: (1) require the structured contextualisation of volcanic hazard assessments or; (2) lay down, at a more granular level, ‘deliberation’ or ‘participation’ rules or guidance covering matters such as: (a) which stakeholders should be actively involved; (b) when; (c) how; and (d) why; for example by reference to the need to make the satisfaction of the risk-related expectations of decision-makers of primary importance.

The practical challenges of contextualisation

Although our theoretical choices provide a coherent framework for hazard assessments, they create multiple challenges. These challenges need to be identified and discussed since they are relevant to the practicalities and standards of contextualisation that we consider later.

Simplicity, certainty, and objectivity

Even though volcanoes exist as ‘objective physical phenomena’, their characterisation can never be simple or a purely objective, value-free and quantitative activity of discovery. Characterisations are social products (Zinn 2008) that are complex, constructed, process-related and dynamic. They are frequently contingent upon existing normative axioms, social conventions and syntax, semantics, and technological pragmatics.Footnote 9 There are no existing rules that will guarantee the objectivity, truth or reliability of contextualisation (Nowotny 2003).

Choices resulting from subjective analysis may become critical within subsequent risk management decisions and may be overlooked (Runge et al. 2015; Leonard et al. 2014). On the other hand, we argue that, when openly identified and discussed, they may represent the variable, or negotiable, aspects of scientific analysis that are integral to, and make contextualisation possible. In short, they may contribute most directly to the utility of the overall analytical effort.

Comprehensibility and integrity

We will refer briefly to, but will not develop, the rich discourse that highlights the challenges of constructing suitably comprehensive, and yet comprehensible, knowledge regarding the complex risk-related parameters of volcanic hazards. By way of illustration, since 1997, if not before, there have been lively debates about, inter alia: (1) the differences between ‘predictions’ and ‘forecasts’; (2) the un-achievability of precise prediction; (3) the merits of ‘deterministic’ and ‘probabilistic’ approaches to forecasting; (4) the use of ‘quantitative’ and/or ‘qualitative’ metrics/narratives; and (5) the merits of communicating sources of and estimates of uncertainties alongside the key assumptions underpinning these (Klein 1997; Newhall et al. 1999; Sparks 2003; Sparks and Aspinall 2004; Rausand 2005; Renn 2008; Aven and Renn 2009; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014; Doorn 2014; Doyle et al. 2014; Stein and Friedrich 2014; Marti 2015; Beven et al. 2015).

Many commentatorsFootnote 10 have addressed the need for reliability, competence, honesty, openness and integrity when handling the complexities, constraints and subjectivities of traditional scientific analysis.Footnote 11 Others have stressed the importance of the pre-crisis relationships within which these difficult issues can be discussed and negotiated (e.g. Leonard et al. 2014).

Materiality

Many commentatorsFootnote 12 have identified differences and perceived tensions (both theoretical and practical) between ‘epistemic’ values relating to the validity, autonomy and objectivity of ‘reliable’ Mode-1 scientific enquiry, and the ‘socio-political’ values of more iterative democratic Mode-2 scientific products. The emergence of contextualisation is therefore significant in that it changes and makes more complex the role of analysts (Weinberg 1972; Nowotny 2003). When described in extreme terms, it changes their role of being isolated providers of off-the-peg Mode-1 ‘evidential’ truth products judged only by their scientific excellence. Instead they become collaborative providers of bespoke ‘problem-related’ Mode-2 value products.Footnote 13

We argue that, if the competencies of reasonably competent hazard assessors do not include identifying and responding to the requirements of, and communicating with, decision-makers, any role that involves contextualisation, if and when undertaken, represents a managerial hazard posing possible managerial risks.

The need for Quality Assurance criteria

Risk governance has a critical normative/ethical dimension and, consistent with this conceptual framework, several commentators (e.g. Grabill and Simmons 1998; Van Nuffelen 2004; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006; Renn 2008; Wachinger and Renn 2010; Thompson 2012) have advocated the need for quality norms for contextualisation.Footnote 14 Our review of the published literature has identified several common themes regarding the need for, and general character of, quality assurance criteria and these are listed in Table 4.

The UN’s Sendai Framework prioritised pre-event risk governance and mitigation before post-event response and recovery. It recognised the importance of knowledge building and promoted the utility of quality standards for risk governance developed by technical organisations and experts (UN/ISDR 2015).

In summary, to preserve ‘good science’, contextualisation must be actively and rationally constrained within structured boundaries (i.e. protocols, rules and standards) that are the product of an iterative dialogue between stakeholders including experts and decision-makers. Yet, advocates of these boundaries provide little, if any, guidance as to how they can be established and, perhaps unsurprisingly, it has been argued that “novel types of quality control probably constitute the most controversial attribute of Mode-2 knowledge production” (Hessels and Lente 2008, 17).

If quality standards are necessary, what standards and processes of standardisation are considered by commentators to be appropriate?

Selecting Quality Assurance criteria

A starting point is to compare Mode-1 and Mode-2 norms, which Weinberg (1972) characterised respectively in terms of ‘truth’ and ‘value’. The quality control of Mode-1 science was traditionally limited to the judgement of a clearly defined community of disciplinary specialists/peers, and based upon context-free and use-free criteria of scientific excellence (Gibbons et al. 1994). Accordingly, the goal of Mode-1 science is “getting the science right” (US/NRC 1996) and, for Nowotny (2003), the relevant criteria, which are epistemic, being relating to the quantification of knowledge validity, include the rigour, dis-interestedness, objectivity, robustness and reliability of scientific methods and practice. In this context, reliability is defined almost exclusively in terms of replicability.Footnote 15

By contrast, the US/NRC 1996 report acknowledges the need for additional quality criteria for Mode-2 science, which has the twin goals of “getting the science right” and “getting the right science”. It states that it is a challenge “to develop reasonable standards for quantitative analysis” and adds that “for both quantitative and qualitative…analysis, technical adequacy is a necessary but not sufficient characteristic: analysis must also be relevant to the given risk” [emphasis added]. Supporting this approach, Renn (2008) argues that Mode-2 contextualised analyses require additional criteria of efficiency and usefulness (i.e. criteria of impact) that reflect the transient contexts of their application. They need to measure the contribution of analysis to risk-mitigation decisions as well as the satisfaction of their makers’ needs and expectations.Footnote 16

Quality Assurance processes and existing standards

What process of quality assurance is best for contextualisation? Hemlin and Rasmussen (2006, 191) advocated a shift of focus away from the quality ‘control’ of post-production knowledge products by traditional academic peer reviewers using only scientific criteria that “tested and checked how [those products] corresponded to reality”. Instead, the objectivity, utility, social relevance and authority of contextualised knowledge products should be established both by continuous ‘quality monitoring’ of outputs and by ‘quality assuring’ knowledge production processes against general standards of production.Footnote 17

Commentators (such as US/NRC 1996; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006; Renn 2008; Wachinger and Renn 2010) assume that ‘general’ or ‘commonly agreed’ quality assurance rules/standards for “fairly and accurately” testing scientific assessments and products (such as volcanic hazards assessments) exist and can be readily found. They allude indirectly to the problem of quality ‘standard equivocality’ that was considered by Bretton et al. (2015) who: (1) argued that objectively measuring the methodological rigour of volcanic hazard assessments (i.e. validating against standards of quality) may present a challenge; and (2) noted that geo-science disciplines in general (and geology/volcanology in particular) and related practices (such as those of ‘geoscientists’ and ‘geologists’) are not regulated in most countries and there are currently no readily accessible international standards of good practice.Footnote 18

The ‘equilibrium of contextualisation’ – an introduction

Developing the notion of ‘standard equivocality’, we here investigate further the direct and indirect consequences of the scrutinised environment within which decision-makers operate. At least nine sources have the potential to influence the quality norms of contextualisation, and thereby drive the processes, outputs and outcomes of contextualisation. They are characterised here as manifestations of: (1) regulatory standards; (2) natural and operational constraints; and (3) stakeholder pressures. In Fig. 1 we introduce the concept of the ‘equilibrium of contextualisation’ that reflects the product of these influences. In the following discussion we introduce each class of influence separately before considering the effect of ‘standard equivocality’.

Contextualisation in Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

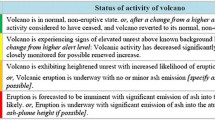

Key: Examples of possible influences, constraints and pressures are given; Hazard Assessments (HA); Decision-makers (DM); Contextualisation is in ‘equilibrium’ when there is ‘balance’ between the influences of quality standards (regulation), natural and operational constraints (reality) and stakeholder pressures (deregulation). Balance is achieved when regulatory sources are effective, quality standards are unequivocal and enforced, within natural and operational constraints stakeholder pressures are addressed, and structured contextualisation preserves scientific methodologies and probity. Disequilibrium and imbalance may result when regulatory sources are ineffective, quality standards are equivocal or unenforced, within natural and operational constraints stakeholder pressures are not addressed, and ad hoc contextualisation fails to preserve traditional standards of scientific probity

Regulatory standards

In this context and for the purposes of this paper, ‘regulation’ means the purposeful control or management of contextualisation that may come in a variety of forms (ranging from slow-changing, rigid, top-down, structured rules to dynamic, organic, bottom-up informal guidance), and from several sources. Six possible sources of regulatory standards are shown in Table 5.

Constraints

‘Natural’ constraints result from the fact that, because “a universal model to understand the behaviour of volcanoes does not exist” (Marti 2015, 372), governance of volcanic risks inevitably involves characterisation of “an inherently complex reality” (Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993, 744).

‘Operational’ constraints, which may be the most significant during an emerging period of volcanic unrest, include those of resources and time. Nowotny (2003) refers to the influence of funding and funders, available resources and, critically, the ability to increase resources during a crisis (e.g. the number of competent scientists and monitoring equipment). Resource and time constraints may have a direct influence on what may be realistic in terms of the scope and depth of analysis. They may also drive or limit contextualisation, for example the choice of data generation and monitoring options in the light of the risk-driven contexts including stakeholders’ preferences.Footnote 19

A dynamic tension may sometimes exist between the constraints (natural and operational) and some of the regulatory influences. By way of example, if one adopts a working assumption that the resources for scientific analysis are usually fixed or inflexible, a scientist may have only a limited number of analytical options from which to select when faced with the requirements of a demanding decision-maker. These options are likely to affect the detail, scope and/or timing of contextualised output. A negotiated balance must be achieved and the pragmatic contextualisation of the variable/negotiable elements of analysis will be the constructed product of deliberation. Adopting the sentiments of Jasanoff (2010), the nuanced product will bear the fingerprints of both scientist and decision-maker.Footnote 20

Stakeholder pressures

Decision-makers frequently request certainty, agreement and consensus from their advisers, and have their own standards, requirements and expectations that they may seek to impose without open discussion and agreement.Footnote 21 Unsurprisingly, those same stakeholders may make it perfectly clear what they want to hear from their advisers to suit their overall approach to risk-related issues and risk mitigation.Footnote 22 Maintenance of traditional standards of scientific probity may therefore be difficult.

The equilibrium of contextualisation - the effect of quality ‘standard equivocality’

The ‘equilibrium’ of contextualisation is the product of the regulatory standards, natural and organisational constraints, and decision-maker pressures (i.e. the variables) already referred to. The equilibrium is ‘dynamic’ (or quasi-static) in that, at any moment in time, the influence of variables in one direction is in aggregate balance with any counter-influences (Oxford University Press 2005). It is also ‘metastable’ in the sense that, when influential variables change, there may be resulting ‘disequilibrium’ and ‘imbalance’ and the former state of ‘equilibrium’ and ‘balance’ may be not reinstated. If it is assumed that regulatory standards and natural constraints are relatively constant, the most significant variables are likely to be operational constraints and stakeholder pressures, and, for obvious reasons, these may often be convolved.

Rothstein et al. (2006) describe an ‘early stage’ societal risk governance environment with few pressures from external regulation and self-regulation. Under such conditions there are few incentives to proceduralise societal risk governance activities. Governance actions tend to be “ad hoc, methodologically diverse and determined by contingent organisational pressures and ways of working” (Rothstein et al. 2006, 9; Bretton et al. 2015). Adopting Rothstein’s model and for the purposes of this paper, we argue that contextualisation is in ‘equilibrium’ when there is ‘balance’ between the influences of quality standards (regulation), natural and operational constraints (reality) and stakeholder pressures (deregulation). Balance is achieved when regulatory sources are effective, quality standards are unequivocal and enforced, within natural and operational constraints stakeholder pressures are addressed, and structured contextualisation preserves scientific methodologies and probity.

The L’Aquila trial highlights the practical difficulties of contextualisation. Alexander (2014a)Footnote 23 has analysed the influence of multiple cultural, political, social and scientific factors before, during and after the disaster, and the complexities of risk governance regimes involving government entities at national, regional and local levels (Alexander 2010, 2013, 2014a, 2014b; Gabrielli and Bucci 2014). Butti (2016) records that Italy’s Appeal Court noted that science communication plays a key role in public safety management. Accordingly, that court accepted that communicators of scientific knowledge have a legal duty to make communications of science “transparent and precise in their content as well as clear and understandable in their style” (Butti 2016). On the facts determined by the lower court, the Appeal Court confirmed that the public officer, who acted as the science communicator, was guilty of “negligence and imprudence” in making a series of reassuring and unnecessarily informal comments to a television journalist, before a meeting of experts, and inviting at-risk people to toast with a famous local wine.

The L’Aquila prosecution was based on alleged facts consistent with a triumph of ‘stakeholder pressures’ (i.e. scientists saying what influential stakeholders wanted them to say) over ‘expert regulation’ (i.e. scientists saying what independent experts would consider was justified by the available scientific evidence and in the light of tried and tested scientific methodologies) in the absence of binding or influential regulation. In summary, it was alleged that a hazard communication had breached standards of contextualisation required by Italian criminal law – binding standards, which were capable of identification at the trial but, for several reasons, were either unknown or ineffective before the tragedy.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we conclude that ‘disequilibrium’ and ‘imbalance’ may result when regulatory sources are ineffective, quality standards are equivocal or unenforced, within natural and operational constraints stakeholder pressures are not addressed, and ad hoc contextualisation fails to preserve traditional standards of scientific probity.

Misuse of the word ‘contextualisation’

We argue that contextualisation, when properly used, is the negotiated product of open and transparent deliberation with stakeholders for the purpose of their risk-related uses. Accordingly, it does not include the covert, intentional or reckless manipulation of the content and/or timing of hazard communications in order: (1) to influence the nature and/or timing of the choices that must be made by risk mitigation decision-makers between multiple possible actions; (2) to reflect the interests of commercial, ideological, religious or local communities; or (3) to incorporate precautionary, conservative, ‘blame-related’ or tactical considerations. In this regard, we appreciate that there is a fine dividing line between, on the one hand, contributing towards the characterisation of the temporal, spatial and physical parameters of volcanic hazards and the identification and assessment of a ‘range’ of related hazard-informed risk mitigation ‘options’ and, on the other hand, actively advocating or influencing ‘particular’ risk mitigation ‘decisions’ that depend inevitably upon socio-political factors, contexts, values and benefit/burden trade-offs.

Recommendations for confronting the challenges of contextualisation: Quality assurance standards for a more structured approach

Our theoretical choices provide a reasoned foundation for contextualised hazard assessments at the volcanic hazard-risk interface. We argue that contextualisations conducted by volcanologists must be carefully constrained within negotiated boundaries assured by quality processes and standards, and make specific recommendations to facilitate a more structured approach.

Good governance of volcanic risks dictates that quality assurance standards for contextualisation should strive:

-

1.

to respect any relevant ‘external’ regulation and ‘self-regulation’ standards;

-

2.

to be derived from an open, transparent and continuing dialogue (an iterative process) between all relevant risk stakeholders, including scientists;

-

3.

to identify, record and preserve certain values perceived as critical to ‘reliable’ scientific analysis; and

-

4.

to identify, record and foster relationships between volcanologists and the stakeholders that use their services, and to enhance the status and utility of those services.

Fischhoff (2013, 14037) suggests that communication is adequate if it meets materiality, proximity, and comprehensibility standards (see Table 2 for further details of these factors and others discussed in this paragraph). Based upon our review of the discourse focussing upon the characteristics of hazard communication, we have concluded that communications should recognise and foster key relationships, and thereby generate shared understandings (i.e. mental models) and constructive sentiments of trust and confidence. We therefore advocate a fourth ‘integrity’ standard that would: (1) complement Fischhoff’s three standards; (2) incorporate the qualities of credibility and legitimacy favoured by Cash et al. (2003) and Sarrki et al. (2014); and (3) provide a more complete suite of standards to monitor, audit; and, if possible, enhance the overall quality of hazard assessments.

We have struggled with the need for a fifth standard to safeguard those values perceived as critical to ‘reliable’ scientific analysis. To resolve this dilemma, we revisited the commentaries of those who wish to preserve certain values attributed by them to the rigour, reliability and robustness of the disciplines of Mode-1 science. Their lexicon alluded to notions of detachment, dis-interestedness, autonomy, objectivity and self-restraint.

We have concluded that a fifth standard would be cumbersome and is unnecessary as Mode-1 science methodologies and behaviours can addressed adequately by, and are in fact integral to, more granular criteria that would properly form the substance of an integrity standard. To put it another way, most, if not all, of the qualities that are likely to be valued by decision-makers (such as competence, comprehensiveness, robustness, objectivity, fairness, transparency, openness and reliability) are hallmarks of integrity, and the building blocks of trust, legitimacy and credibility.

We accept that the utility of scientific knowledge should be established by the continuous quality ‘monitoring’ of not only ‘outputs’ (i.e. knowledge products) but also quality ‘assuring’ the knowledge production ‘processes’ that are claimed to be scientific. Accordingly, quality assurance has a remit that reaches beyond analytical ‘output’ improvement and includes continuous analytical ‘process’ adaption. We thus advocate the four quality assurance standards detailed in Table 6.

Conclusions

A weak social constructivist approach to risk governance, which embraces relativist knowledge communication, provides a coherent theoretical framework for the communication of unavoidable scientific complexities and uncertainties at the volcanic hazard-risk interface.

Within an iterative, non-linear, analytic-deliberative model, the communication of knowledge is integral to all parts of governance, and the capacities, expectations, sentiments and actions of decision-makers thus become not just relevant but paramount. Assessments of volcanic hazards should no longer assume an intrinsic status or functional role. Any status or role should reflect the existence and qualities of ‘relationships’ between volcanologists and decision-makers, and be derived from, and a consequence of, the subsequent sentiments and behaviours of decision-makers.

If it is accepted that decision-makers and their knowledge requirements are important, hazard assessments must be contextualised to make them more risk-decision focussed. If they are not already open post-L'Aquila, the black boxes of hazard analysis and communication must be opened so that their respective roles and risk-governance impacts can be reappraised. Although there is evidence of a slow shift towards initiatives assessing more iterative forms of governance, the processes of deliberation being used seem to lack formal recorded structures. Insufficient guidance exists for managing the practicalities and standards of hazard contextualisation and, to investigate these issues, we introduce two novel concepts. The ‘scrutiny dimension’ of risk governance is the slow-changing regulatory context that may influence the ‘managerial dimension’ of risk and, thereby, the dynamics of contextualisation. The metastable ‘equilibrium of contextualisation’ explains the consequences of the quality ‘standard equivocality’ identified by Bretton et al. (2015).

To preserve core values of traditional scientific probity, many commentators have argued that contextualisation conducted by scientists must be constrained within certain boundaries. They have given little, if any, guidance as to how these boundaries can be established, however. In response to the challenge posed by this lacuna, we argue that the working practices of contextualisation must be more structured, and should strive to be open, transparent and fully articulated. Contextualisation, that meets our proposed quality assurance standards of materiality, proximity, comprehensibility and integrity may enhance hazard assessments and, thereby, the utility of their applications (outputs) and impact of those outputs (outcomes). Utility and impact should be measured by reference to the sentiments and actions of decision-makers.

Notes

The second paper is “Hazard communication by volcanologists: Part 2 - Quality standards for volcanic hazard assessments” [Bretton et al, J Appl. Volcanol. DOI 10.1186/s13617-018-0079-8, 2018]

Analyses of the past and present, and statements regarding the future, are very difficult because “a universal model to understand behaviour of volcanoes does not exist” (Marti 2015, 372). “Each volcano has its own peculiarities depending on magma variables…rock rheology, stress field, geodynamic environment and local geology” (Marti 2015, 372). Even though volcanoes are notoriously individualistic, with ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ personalities, past volcanic activity is not always a good guide to the future (Fournier d'Albe 1979; Francis and Oppenheimer 2004; Sparks et al. 2013).

E.g. those involving data sources and key value assumptions, models, conditions, constraints and limitations.

Our choices are made at a time when objectivist and decisionist approaches to risk governance, which are based upon the assumption of an achievable segregation of ‘context and value-free’ and ‘context and value-rich’ domains, are under pressure (Fischer 2000; Pielke 2004; IRGC 2005; Renn 2008; Millstone 2009). Specifically, the current role of volcanologists, when acting as hazard analysts, appears to some commentators from both general scientific and geo-scientific backgrounds to be divisive, blurred, porous and confused (Peterson 1996; Nowotny 2003; Renn 2008; Ronan et al. 2000; Stirling 2010; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2012; Marzocchi et al. 2012; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014; Bretton et al. 2015; OECD 2015).

These three [dimensions of risk] all contribute to attempts to estimate or grade risk. In risk analysis, the context (management capacity and related actors) determines the limits, the reasons, the purpose and the interactions to be considered. Analysis has to be congruent with the context and this must be taken into account when analysing the sum of the contributing factors. If not, the analysis would be totally irrelevant or useless (Cardona 2004, 47).

DEVORA is a multi-agency, multi-disciplinary collaborative research programme which is led by volcanologists at the University of Auckland and GNS Science.

Weinberg 1972; Freudenburg 1988; Horlick-Jones 1998; Funtowicz and Ravetz 1990; Wynne 1992; Funtowicz and Ravetz 1992; Gibbons et al. 1994; Laudan 1996; Bruijn and ten Heuvelhof 1999; Lupton 1999; Van Asselt and Rotmans 2002; Jasanoff 2002; Merz and Thieken 2005; IRGC 2005; Renn 2008; Mellor 2008; Parascandola 2010; Jasanoff 2010; Spieghalter and Riesch 2011; Aspinall and Cooke 2013; Rougier 2013; Rougier and Beven 2013; Hincks et al. 2014; Cornell and Jackson 2013; Freer et al. 2013; Beven et al. 2015; OECD 2015.

Renn and Levine 1991; Siegrist and Cvekovich 2000; Frewer et al. 2003; Poortinga and Pidgeon 2003; Poortinga et al. 2004; Siegrist and Gutscher 2006; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006, 188; Pielke 2007; Wilson et al. 2007; Eiser et al. 2009; Renn 2008; Haynes et al. 2008b; Doyle and Johnston 2011; Fischhoff 2013; Ulusoy 2012; Owen et al. 2013; IAVCEI 2013 Newsletter No. 4; Sparks et al. 2013; Siegrist 2014; Pierson et al. 2014; Potter et al. 2014; Leonard et al. 2014; Donovan and Oppenheimer 2014; Doyle et al. 2015; Christie et al. 2015; OECD 2015; Mothes et al. 2015; Scolobig et al. 2017; Preuner et al. 2017

Pierson et al. (2014, 21), citing Pielke (2007), Haynes et al. (2008b), argue that four qualities exhibited by scientists enhance their trustworthiness in the eyes of the public. These are: (1) reliability (i.e. consistency and dependability in what they say), (2) competence (i.e. having the skills and ability to do the job); (3) openness (i.e. having a relaxed, straightforward attitude and being able to mix well and become ‘part of the community’); and (4) integrity (i.e. having an impartial and independent stance). On a similar note, the OECD (2015, 34) noted “it should be recognised that openness and transparency are important elements in maintaining public trust in scientific advice during crises”.

Van Nuffelen (2004) refers to “inevitable communication problems” and the practical and cognitive difficulties of “scholastic distortion”.

These norms have been referred to as rules for how science is conducted (Grabill and Simmons 1998), an ethical threshold for scientific investigation (Van Nuffelen 2004), commonly agreed standards of validation (Renn 2008), benchmarks and performance standards (Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006), and integration rules and standards (Wachinger and Renn 2010). The US/NRC's definition of analysis expressly acknowledges that there may be “strong practical reasons for standardised, replicable and defensible analytic procedures…capable of independent review” (US/NRC 1996 102).

On a similar note, Renn (2008) states that analytical competence is typically evaluated by criteria and established rules that have been developed within the respective disciplines from which the analytical theories and methods originate.

Renn (2008) is more specific arguing that deliberation can assist scientific analysis in several ways. Deliberation can enhance analysis by incorporating information from disparate sources including local, indigenous, experiential and circumstantial knowledge sources Such as those championed by Baxter et al. (1998), Loughlin et al. (2002), Cronin et al. (2004a, 2004b), Cashman and Giordano (2008), Mercer and Kelman (2010), McCall and Peters-Guarin (2012), Cornell and Jackson (2013) and Pardo et al. (2015); representing an indirect endorsement of our materiality and integrity standards. Deliberation can determine what kind of analysis a risk-mitigation decision requires (a direct reference to the need for materiality), and whether that analysis is appropriately balanced (an indirect reference to a need for integrity). Lastly, deliberation can determine how to communicate “user–friendly” (i.e. bespoke as opposed to one-size-fits all) analytical results – an indirect reference to our materiality, comprehensibility and proximity standards.

Renn (2008, 275) refers to evidence claims, such as hazard communications, being “fairly and accurately tested against commonly agreed standards of validation”. The US/NRC's definition of analysis, summarised in [Additional file 1], expressly acknowledges that there may be “strong practical reasons for standardised, replicable and defensible analytic procedures…capable of independent review”.

Addressing the same issue, other commentators refer to the “maturity of scientific knowledge” and acknowledge that many “decision options require systematic knowledge that is not available, still in its infancy or in an intermediate status” (Renn 2008, 292; Starr and Whipple 1980; Horlick-Jones 1998; Horlick-Jones 2007). In apparent support for the above sentiments, and to put in context their recommendations for volcanic hazard map standards, it is telling that Leonard et al. (2014) noted a lack of relevant authoritative international guidance in their 2012 Tongariro eruption crisis case study.

Weinberg (1992) refers to the need for ‘engineering judgement’ when decisions must be made on incomplete data and constrained by time and resource limitations. A judgement of this nature is a good example of unstructured contextualisation; however, great care must be taken to distinguish between, and not to misuse, the terms ‘engineering judgement’ and ‘expert judgement’. The latter is not arbitrary, having to satisfy various fundamental principles (Skipp 1993).

By way of illustration, it might be agreed that it would be appropriate to prioritise certain analytical activities, and/or to target areas of greatest perceived societal risk exposure or vulnerability, such as a particular valley, an area of high population/vulnerability, or critical infrastructure sites (e.g. a bridge, dam, desalination plant, hospital or airport).For contextualised communication, the issues to be addressed would include: (1) analytical content – format, numerical and narrative expressions of probability and analytical confidence, assumptions, jargon and graphics; (2) ancillary advice – the adequacy, location and funding of monitoring resources, hazard and risk mitigation and monitoring safety; and (3) delivery – timing, means, givers and receivers (see e.g. Jolly and Cronin 2014).

Stirling (2010) notes that policy-makers often prefer expert advice presented as a “single ‘definitive’ interpretation”. He warns that, in response, there is a tendency for scientists to reach and present a consensus opinion and, not only to understate uncertainties within quantitative advice, but to present qualitative advice that understates ambiguities and ignorance, and contains aggregated beliefs.

Alexander 2014a, 1 “…transforming the findings of earth sciences…into information that can be used to protect citizens”

Abbreviations

- CEOS:

-

Committee on Earth Observation Satellites

- DEVORA:

-

DEtermining VOlcanic Risk in Auckland

- DRM:

-

Disaster Risk Management

- ESRC:

-

Economic and Social Research Council

- IAVCEI:

-

International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior

- IFRC:

-

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- ISDR:

-

International Strategy for Disaster Reduction

- NERC:

-

Natural Environment Research Council

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- RR:

-

Risk reduction

- STREVA:

-

Strengthening Resilience in Volcanic Areas

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- UN:

-

United Nations

- UOB:

-

University of Bristol, United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States of America

- US/NRC:

-

National Research Council of the United States of America

- VOBP:

-

Volcano Observatory Best Practice

- VUELCO:

-

Volcanic Unrest in Europe; Latin America: Phenomenology, eruption precursors, hazard forecast, and risk mitigation

References

Alexander DE. The L'Aquila Earthquake of 6 April 2009 and Italian Government Policy on Disaster Response. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research. 2010;2(4):325–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390459.2010.511450.

Alexander DE. An evaluation of medium-term recovery processes after the 6 April 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, Central Italy. Environmental Hazards. 2013;12(1):60–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2012.689250.

Alexander DE. Communicating earthquake risk to the public: the trial of the “L’Aquila Seven”. Nat Hazards 2014a; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1062-2.

Alexander DE. Reply to a comment by Franco Gabrielli and Daniela Di Bucci: “Communicating earthquake risk to the public: the trial of the “L’Aquila Seven””. Nat Hazards 2014b; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1323-0.

Arnstein SR. A ladder of participation. J Am Plann Assoc. 1969;35(4):216–24.

Aspinall WP. Check your legal position before advising others. Online 14 September 2011. Nature. 2011;477:250. https://doi.org/10.1038/477251a

Aspinall WP, Cooke RM (2013) Quantifying scientific uncertainty. In: Rougier J, Sparks RSJ, Hill L (eds.) Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Natural Hazards. Cambridge University Press

Aven T, Renn O. On risk defined as an event where the outcome is uncertain. Journal of Risk Research. 2009;12(1):1–11.

Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D. Mapping Vulnerability – Disasters. London and New York: Development & People Earthscan; 2004.

Bartley RL. "When Science Tangles with Politics", Congress lomIl. Record, v. 117, no. 151. 12 October 1971, pp. S16173–16174. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED059074.pdf.

Basher R. Global early warning systems for natural hazards: systematic and people-centred. Phil Trans R Soc. 2006;364:2167–82.

Baxter PJ, Neri A, Todesco M. Physical modelling and human survival in pyroclastic flows. Nat Hazards. 1998;17:163–76.

Beck U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London and Newbury Park: Sage; 1992.

Ben-Ari A, Or-Chen K. Integrating competing conceptions of risk: A call for future direction of research. Journal of Risk Research. 2009;12(6):865–77.

Bernknopf RL, Brookshire DS, Thayer MA. Earthquake and volcanic hazard notices: An economic evaluation of changes in risk perception. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 1990;18:35–49.

Beven KJ, Aspinall WP, Bates PD, Borgomeo E, Goda K, Hall JW, Page T, Phillips JC, Rougier JT, Simpson M, Stephenson DB, Smith PJ, Wagener T, Watson M (2015) Epistemic uncertainties and natural hazard risk assessment – Part 1: A review of the issues. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci Discuss 3, 7333–7377, www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/3/7333/2015/ doi:https://doi.org/10.5194/nhessd-3-7333-2015

Bird DK, Gìsladóttir G. Residents’ attitudes and behaviour before and after the Eyjafjallajökull eruption – a case study from southern Iceland. Bull Volcanol. 2012;74:1263–79.

Birkmann J, Setiadi N, Fielder G (2015) A culture of resilience and preparedness: The 'lastmile' case study of tsunamin risk in Padang, Indonesia. In: Krüger F, Bankoff G, Cannon T, Orlowski B, Schipper ELF (eds). Cultures and Disasters – Understanding cultural framings in disaster risk management. ISBN 978-0-415-74560. Routledge; 2015. p. 235–54.

Blockley D, editor. Engineering Safety. London: MacGraw-Hill International series in Civil Engineering; 1992.

Bostrom A. Putting seismic risk and uncertainty on the map, a response to Pang's paper “Visualising uncertainty in natural hazards”. In: Bostrom A, French S, Gottlieb S, editors. Risk Assessment, Modelling and Decision Support. Volume 14 of Risk, Governance and Society, vol. 14. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2008. p. 306–10.

Bretton RJ (2014) The role of science in the rule of law. https://www.expertsinuncertainty.net/Portals/60/Documents/Rome%20Presentations/Richard%20Bretton.pdf.

Bretton RJ, Aspinall W. Risk assessments face legal scrutiny. Nature. 2017;550:188. https://doi.org/10.1038/550188b.

Bretton RJ, Gottsmann J, Aspinall WP, Christie R. Implications of legal scrutiny processes (including the L'Aquila trial and other recent court cases) for future volcanic risk governance. Journal of Applied Volcanology. 2015;4:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-015-0034-x.

Bretton RJ, Gottsmann J, Christie R. The Role of Laws Within the Governance of Volcanic Risks. Advs in Volcanology. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/11157_2017_29.

Bruijn JA, ten Heuvelhof EF. Scientific expertise in complex decision-making processes. Science and Public Policy. 1999;26(3):151–61.

Budescu DV, Broomell S, Por H-H. Improving communication of uncertainty in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:299–308.

Butti L (2016) L’Aquila 2009 Earthquake – Science and its communication on trial. Lecture slides for Lunchtime Talk at Clare Hall College, Cambridge on 27 October 2016.

Calder E, Wagner K, Ogburn SE. Volcanic Hazard Maps. In: Loughlin SC, Sparks RSJ, Brown SK, Jenkins SF, Vye-Brown C, editors. Global Volcanic Hazards and Risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

Callon M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fisherman of St. Brieuc Bay. In: Law J, editor. Paul Power: Action and Belief: A new sociology of knowledge? London: Routledge and Keegan; 1986a.

Callon M. The sociology of an actor-network: the case of the electronic vehicle. In: Callon M, Law J, Rip A, editors. Mapping the dynamics of science and technology: Sociology of science in the real world. Houndsmill. UK: Macmillan; 1986b.

Cardona OD. The need for rethinking the concepts of vulnerability and risk from a holistic perspective: A review and criticism for effective risk management. In: Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D, editors. Mapping Vulnerability – Disasters. London and New York: Development & People Earthscan; 2004. p. 37–51.

Carreno ML, Cardona OD, Barbat AH. New methodology for urban seismic risk assessment from a holistic perspective. Bull Earthquake Eng. 2012;10:547–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-011-9302-2.

Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Guston DH, Jäger J, Mitchell RB. Knowledge systems for sustainable development Proc. Natl Acad Sci (PNAS). 2003;100:8086–91.

Cashman KV, Giordano G. Volcanoes and human history. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 2008;176(2008):325–9.

Christie R, Cooke O, Gottsmann J. Fearing the knock on the door: critical security studies insights into limited cooperation with disaster management regimes. Journal of Applied Volcanology. 2015;4:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-015-0037-7.

Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) (2013) Disaster Risk Management Observation Strategy Issue 2. CEOS

Cornell SE. Improving stakeholder engagement in flood risk management decision making and delivery. R&D Technical Report 2006, SC040033/SR2. Bristol: Environment Agency; 2006.

Cornell SE, Jackson MS. Social science perspectives on natural hazards risk and uncertainty. In: Rougier J, RSJ S, Hill L, editors. Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Natural Hazards. Cambridge: University Press; 2013. p. 502–47.

Crichton D. The risk triangle. In: Natural Disaster Management. London: Tudor Ross; 1999. p. 102–3.

Cronin SJ. The Auckland Volcano Scientific Advisory Group during Exercise Ruaumoko: observations and recommendations. Civil Defence Emergency Management: Exercise Ruaumoko. Auckland: Auckland Regional Council; 2008.

Cronin SJ, Gaylord DR, Charley P, Wallez S, Alloway BV, Esau JW. Participatory methods of incorporating scientific with traditional knowledge of volcanic hazard assessment in Ambae Island, Vanuatu. Bull Volcanol. 2004a;66:652–68.

Cronin SJ, Petterson MJ, Taylor MW, Biliki R. Maximising multi stakeholder participation in government and community volcanic hazard management programs: a case study from Savo, Solomon Islands. Nat Hazards. 2004b;33:105–36.

De la Cruz-Reyna S, Tilling RI. Scientific and public responses to the on-going volcanic crisis at Popocatepetl Volcano, Mexico: Importance of an effective hazards-warning system. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 2008;170(2008):121–34.

Donovan A, Oppenheimer C. Governing the lithosphere: Insights from Eyjafjallajökull concerning the role of scientists in supporting decision-making on active volcanoes. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:B03214. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB009080,2012.

Donovan A, Oppenheimer C. Science, policy and place in volcanic disasters: Insights from Montserrat. Environ Sci Policy. 2014;38:150–61.

Doorn N. The blind spot in risk ethics: Managing natural hazards. Risk Analysis, Society for Risk Analysis. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12293.

Douglas D. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. London: Routledge; 1992.

Doyle EEH, Johnston DM. Science advice for critical decision-making. In: Paton D, Violanti J, editors. Working in High Risk Environments: Developing Sustained Resilience. Springfield, Illinois, USA: Charles C Thomas; 2011. p. 69–92.

Doyle EEH, Johnston DM, McClure J, Paton M. The communication of uncertain scientific advice during natural hazard events. N Z J Psychol. 2011;40(4):39–50.

Doyle EEH, McClure J, Johnston DM, Paton D. Communicating likelihoods and probabilities in forecasts of volcanic eruptions. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 2014;272:1–15.

Doyle EEH, Paton D, Johnston DM. Enhancing scientific response in a crisis: Evidence-based approaches from emergency management in New Zealand. Journal of Applied Volcanology. 2015;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s.13617-014-0020-8.

Driedger C, Neal CA, Knappenberger TH, Needham DH, Harper RB, Steele WP. Hazard information management during the autumn 2004 reawakening of Mount St. Helens Volcano, Washington. In: Sherrod DR, Scott WE, Stauffer PH, editors. A Volcano Rekindled: The Renewed Eruption of Mount St. Helens, 2004-2006, vol. 1750. U.S.: Geological Survey Professional Paper; 2008. p. 2008.

Eiser JR, Stafford T, Henneberry J, Cateney P. “Trust me, I’m a Scientist (Not a Developer)”: Perceived expertise and motives as predictors of trust in assessment of risk from contaminated land. Risk Anal. 2009;29(2):288–97.

Fearnley C, Beaven S. Volcano alert level systems: Managing the challenges of effective volcanic crisis communication. Bull Volcanol. 2018;80:46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-018-1219-z.

Fearnley CJ. Assigning a volcano alert level: negotiating uncertainty, risk, and complexity in decision-making processes. Environmental and Planning A. 2013;45(8):1891–911. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4542.

Fearnley CJ, McGuire WJ, Davies G, Twigg J. Standardisation of the USGS Volcano Alert Level System (VALS): analysis and ramifications. Bull Volcanol. 2012;74:2023–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s0445-012-0645-6.

Fischer F. Citizens, Experts and the Environment: The politics of local knowledge. Durham, NC: Taylor & Francis; 2000.

Fischhoff B (2013) The sciences of science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Science of the USE (PNAS) Vol. 111 suppl. 4 14033-14039

Fiske R. Volcanologists, Journalists, and the Concerned Local Public: A Tale of Two Crises in the Eastern Caribbean. In: Explosive Volcanism: Inception, Evolution and Hazards. Geophys. Study Committee, National Research Council. Washington: National Academy Press; 1984. p. 170–6.

Fournier d'Albe EM. Objectives of volcanic monitoring and prediction. J Geol Soc London. 1979;136:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsjgs.136.3.0321.

Francis P, Oppenheimer C. Volcanoes. Oxford: University Press; 2004.

Freer J, Beven KJ, Neal J, Schumann G, Hall J, Bates P. Flood risk and uncertainty. In: Rougier J, RSJ S, Hill L, editors. Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Natural Hazards. Cambridge: University Press; 2013.

Frenzen PM, Matarrese MT. Managing public and media response to a reawakening volcano: Lessons from the 2004 Eruptive Activity of Mount St. Helens. In: Sherrod DR, Scott WE, Stauffer PHA, editors. Volcano Rekindled: The Renewed Eruption of Mount St. Helens, 2004-2006. U.S.: Geological Survey Professional Paper; 2008. p. 1750.

Freudenburg WR. Perceived risk, real risk: Social science and the art of probabilistic risk assessment. Science. 1988;242:44–9.

Frewer LJ, Scholderer J, Bredahl L. Communicating about the risks and benefits of genetically modified foods: the mediating role of trust. Risk Anal. 2003;23:1117–3.

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR. Uncertainty and quality in science for policy. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1990.

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR. Three types of risk assessment and the emergence of post-normal science. In: Krimsky S, Golding D, editors. Social Theories of Risk. Westport and London: Praeger; 1992. p. 251–73.

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR. Science for the post-normal age. Futures. 1993;25:735–55.

G8 (2005) Gleneagles Response to the Indian Ocean Disaster, and Future Action on Disaster Risk Reduction: Statement. http://www.commit4africa.org/content/gleneagles-g8-response-indian-ocean-disaster-and-future-action-disaster-risk-reduction.

Gabrielli F, Di Bucci D (2014) Comment on “Communicating earthquake risk to the public: the trial of the ‘L’Aquila Seven’ by David Alexander”, Nat Hazards. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1322-1

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H, Schwarzman S, Scott P, Trow M. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage; 1994.

Grabill JT, Simmons WM. Toward a critical rhetoric of risk communication: Producing citizens and the role of technical communicators. Technical Communication Quarterly. 1998;7(4):415–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572259809364640.

Haynes K, Barclay J, Pidgeon N. Volcanic hazard communication using maps: an evaluation of their effectiveness. Bull Volcanol. 2008a;70:123–38.

Haynes K, Barclay J, Pidgeon N. The issue of trust and its influence on risk communication during a volcanic crisis. Bull Volcanol. 2008b;70:605–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-007-0156-z.

Haynes K, Barclay J, Pidgeon N. Whose reality counts? Factors affecting the perception of volcanic risk. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 2008c;172(2008):259–72.

Hemlin S, Rasmussen SB. The Shift in Academic Quality Control. Science, Technology and Human Values. 2006;31(2):173–98.

Hessels LK, van Lente H, (2008) Re-thinking new knowledge production: A literature review and a research agenda. Research policy 37 (2008) 740-760

Hicks A, Barclay J, Simmons P, Loughlin S. An interdisciplinary approach to volcanic risk reduction under conditions of uncertainty: a case study of Tristan da Cunha. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci Discuss. 2013;1:7779–820, 20913 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/1/7779/2013/. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhessd-1-7779-2013.

Hincks A, Barclay J, Simmons P, Loughlin S. Retrospective analysis of uncertain eruption precursors at La Soufrière volcano, Guadeloupe, 1975–77: volcanic hazard assessment using a Bayesian Belief Network approach. Journal of Applied Volcanology. 2014;3:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-5040-3-3.