Abstract

Background

Endotoxins can induce an excessive inflammatory response and result in microcirculatory dysfunction. Polymyxin-B hemoperfusion (PMX-HP) has been recognized to effectively remove endotoxins in patients with sepsis and septic shock, and a rat sepsis model revealed that PMX-HP treatment can maintain a better microcirculation. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the effect of PMX-HP on microcirculation in patients with septic shock.

Methods

Patients with septic shock were enrolled and randomized to control and PMX-HP groups. In the PMX-HP group, patients received the first session of PMX-HP in addition to conventional septic shock management within 24 h after the onset of septic shock; the second session of PMX-HP was provided after another 24 h as needed.

Results

Overall, 28 patients finished the trial and were analyzed. The mean arterial pressure and norepinephrine infusion dose did not differ significantly between the control and PMX-HP groups after PMX-HP treatment. At 48 h after enrollment, total vessel density (TVD) and perfused vessel density (PVD) were higher in the PMX-HP group than in the control group [TVD 24.2 (22.1–24.9) vs. 21.1 (19.9–22.9) mm/mm2; p = 0.007; PVD 22.9 (20.9–24.9) vs. 20.0 (18.9–21.6) mm/mm2, p = 0.008].

Conclusions

This preliminary study observed that PMX-HP treatment improved microcirculation but not clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock at a low risk of mortality. Nevertheless, larger multicenter trials are needed to confirm the effect of PMX-HP treatment on microcirculation in patients with septic shock at intermediate- and high-risk of mortality.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov protocol registration ID: NCT01756755. Date of registration: December 27, 2012. First enrollment: October 6, 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01756755

Similar content being viewed by others

Severe microcirculatory dysfunction is associated with multiple organ injury and mortality in patients with septic shock [1,2,3]. Microcirculatory dysfunction includes endothelial damage, impaired vasoregulation, and coagulation activation [4, 5], and this dysfunction may present as capillary leakage, hypotension, microthrombosis and impair the tissue perfusion. One of the leading causes of microcirculatory dysfunction is endotoxin, which can induce excessive immune reactions, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress [6]. Endotoxin injury can be reduced by antagonization or removal strategy. A Toll-like receptor 4 antagonist was reported to improve microcirculation in endotoxemic rats [7]. Moreover, direct hemoperfusion with a polymyxin B-immobilized column was determined to be effective to reduce circulating endotoxins [8]. A rat sepsis model revealed that removal of circulating endotoxin using polymyxin-B hemoperfusion (PMX-HP) can maintain a better microcirculation and lower damage markers [9]. Notably, poor microcirculation parameters reflect inadequate tissue perfusion [10, 11]; thus, the improvement of microcirculation may ensure adequate tissue perfusion and prevent ischemic damage of organs. To the best of our knowledge, no clinical study has investigated the effect of PMX-HP treatment on microcirculation in patients with septic shock. Therefore, we hypothesized that PMX-HP treatment can improve microcirculation by removing endotoxin and reducing endotoxin-related microcirculatory dysfunction. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the effects of PMX-HP on microcirculation in patients with septic shock.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

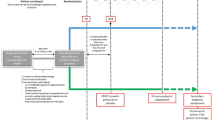

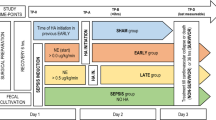

This prospective, randomized, controlled study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (approval number: 201208067RIB) and registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov protocol registration system (ID: NCT01756755). This study was conducted between October 2013 and July 2018. The definition of sepsis and septic shock met the criteria of international consensus definition [12, 13]. Inclusion criteria for patients with septic shock were intra-abdominal infection with adequate management, proven gram-negative bacteria infection, or endotoxin activity assay (EAA) level of > 0.6 EAA units in patients with pneumonia, blood stream infection, or urinary tract infection. Exclusion criteria were age less than 20 years, the onset of sepsis and septic shock more than 24 h at enrollment, pregnancy, participation in interventional trials at other intensive care units (ICUs) within 30 days before enrollment, undergoing organ transplant surgery within 1 year before enrollment, life-expectancy less than 30 days, history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) within 30 days before enrollment, signed no-CPR consent before enrollment, hemophilia, allergic history to polymyxin B or heparin, uncontrolled bleeding within 24 h before enrollment, renal replacement therapy before enrollment, white blood cells count less than 0.5 K/uL or platelet count less than 50 K/uL, human immunodeficiency virus infection, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score higher than 30 at enrollment, and non-native speakers. Moreover, patients were not enrolled if they declined to participate. Informed consent was obtained from patients’ legally authorized representatives before enrollment. After enrollment, patients were randomly assigned to the control and PMX-HP groups based on the opaque, sealed envelope technique. In the control group, septic shock was treated according to the practice guidelines for sepsis and septic shock [13, 14]. In the PMX-HP group, patients received one session of PMX-HP within 24 h after the onset of septic shock in addition to conventional septic shock management. Sublingual microcirculation video sequences were recorded using a sidestream dark field video microscope (MicroScan; Microvision Medical, Netherlands) at the following time points: T0, enrollment; T1, 24–26 h after T0; and T2, 48 h after T0. At T1, patients in the PMX-HP group received a second session of PMX-HP if the patient’s septic shock was not resolved. At each time point, clinical data, mean arterial pressure (MAP), norepinephrine infusion dose, APACHE II score, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, laboratory data, the length of ICU and hospital stay, and survival status at 28 days were recorded. Arterial oxygen tension/fraction of inspired oxygen concentration (PaO2/FiO2) ratio was recorded if the data were available.

PMX-HP treatment protocol

PMX-HP was performed using an extracorporeal hemoperfusion cartridge with polymyxin B immobilized on polystyrene fibers (Toraymyxin PMX-20R, Toray Industries, Tokyo, Japan). Cartridge and circuit were first washed using 4 L 0.9% saline and then primed with 4000 IU heparin in 1 L 0.9% saline. Vascular access was obtained using double-lumen venous catheter. The blood was perfused at a flow rate of 100 to 150 mL/min for 2 h. During PMX-HP treatment, patients received heparin at a loading dose of 3000 IU and a maintenance dose of 20 U/kg/h following manufacturer’s instruction. Notably, the heparin dose was adjusted according to our heparin dosing score protocol in patients with coagulopathy to avoid any bleeding event [15].

Measurements of sublingual microcirculation

Five video sequences (length: 20 s each) were recorded at different sites on ventral aspect of the tongue according to the consensus guidelines [16] by one of the two operators, a clinical research nurse (Ms. Wang) and Dr. Yeh, who had been trained and taken more than 300 and 100, respectively, microcirculation recordings for patients and health volunteers. These video sequences were digitally stored with code numbers to ensure the anonymity of patient information. Subsequent microcirculation analyses were performed according to the consensus guidelines [16] by a research assistant (Ms. Wu, who had been trained and analyzed more than 3000 video sequences of animal and human microcirculation) who was blinded to the patient information. Three sequences with appropriate image quality were selected for analysis using the semi-automated analysis software Automated Vascular Analysis 3.0 [17]. Inappropriate image quality included pressure or secretion artifact, and inadequate focus and contrast adjustments [17]. The following parameters were investigated: (a) total vessel density (TVD; vessels less than 20 μm), (b) perfused vessel density (PVD), (c) proportion of perfused vessels (PPV), and (d) microvascular flow index (MFI) score. TVD was automatically calculated by the software. The blood flow in small vessels was classified using an ordinal scale of 0–3, and small vessels with a blood flow classification of 2 or 3 were considered as perfused vessels [18]. PVD was semi-automatically calculated by the software. The MFI scores were semiquantitatively calculated according to suggestions made at the roundtable conference [19].

End points and sample size analysis

The primary end point was the difference in PVD between the control and PMX-HP groups at T2. Based on our experience, 20 patients per group were sufficient to detect a 12% difference of PVD between the two groups, with an α level of 0.05 (two-tailed) and a β level of 0.2, assuming a controlled mean PVD of 20.0 mm/mm2 with a standard deviation of 3.0. The secondary end points included the difference in APACHE II score, SOFA score, and MAP between the two groups at T2.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed numerical data were expressed as means (standard deviation) and compared using t test. Non-normal distributed numerical data, TVD, and PVD were expressed as medians (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables were described as percentages and were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Intention-to-treat analysis was used for most comparisons between the two groups. Intention-to-treat, as-treated, and per-protocol analysis were used to investigate the difference in PVD between the two groups. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 223 patients with severe sepsis and septic shock were initially considered for inclusion in this trial (Fig. 1). Subsequently, 194 patients were excluded, and 29 patients were randomized. However, in the PMX-HP group, one patient signed no CPR consent and decided to pursue palliative care after enrollment. Therefore, finally, 28 patients were analyzed. In the PMX-HP group, 10 patients received one session of PMX-HP, and 4 patients received two sessions of PMX-HP. In the control group, one patient requested self-financed PMX-HP and received one session of PMX-HP. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Patients’ characteristics did not differ significantly between the control and PMX-HP groups.

Hemodynamic parameters, laboratory data, and clinical outcomes

Patients’ hemodynamic data, laboratory data, and treatments for septic shock are listed in Table 1. MAP and norepinephrine infusion dose did not differ significantly between the control and PMX-HP groups at T1 and T2. Only one patient in the PMX-HP group required an additional infusion of epinephrine at enrollment, but the infusion was discontinued 4 h after PMX-HP treatment. Total fluid supplementation within the first 48 h did not differ significantly between the PMX-HP and control groups [6025 (4690–7623) vs. 6034 (5012–7247) mL, p = 0.946]. No significant intergroup differences were noted regarding changes in the SOFA score and APACHE II score from T0 to T2. The total urine output over 48 h after enrollment did not differ significantly between the PMX-HP and control groups [3615 (2170–5075) vs. 3365 (2373–5078) mL, p = 0.946]. The creatinine level at T1 was nonsignificantly lower in the PMX-HP group than in the control group [1.1 (0.6) vs. 1.9 (1.5) mg/dL, p = 0.110]. The platelet counts did not differ significantly between the PMX-HP and control groups at T1 and T2 [T1, 134 (63) vs. 162 (141) k/μL, p = 0.504; T2, 122 (47) vs. 127 (83) k/μL, p = 0.880]. PaO2/FiO2 ratio did not differ significantly between the PMX-HP and control groups [T0, n = 14 vs 14, 244 (125) vs. 265 (147), p = 0.689; T1, n = 10 vs. 13: 346 (133) vs. 346 (116), p = 0.999; T2, n = 8 vs. 6: 342 (167) vs. 285 (117), p = 0.495].

Patients’ clinical outcomes and survival are presented in Table 2. No significant intergroup differences were noted regarding the ICU stay, hospital stay, and 28-day survival.

Microcirculation parameters

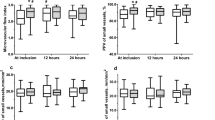

A total of 420 video sequences of sublingual microcirculation were recorded for the 28 enrolled patients, and 252 video sequences with appropriate image quality were analyzed according to the description in Methods. Examples of sublingual microcirculation images are presented in Fig. 2. TVD, PVD, PPV, and MFI of the two groups are presented in Fig. 3. The intent-to-treat analysis at T1 revealed no significant intergroup differences related to TVD and PVD. At T2, TVD and PVD were higher in the PMX-HP group than in the control group [TVD 24.2 (22.1–24.9) vs. 21.1 (19.9–22.9) mm/mm2; p = 0.007; PVD 22.9 (20.9–24.9) vs. 20.0 (18.9–21.6) mm/mm2, p = 0.008]. As-treated analysis and per-protocol analysis of TVD and PVD at T1 and T2 are presented in Table 3.

Comparison of microcirculation parameters between the control and PMX-HP groups. n = 14 patients in each group. Time points: T0, at enrollment; T1, at 24–26 h after enrollment; and T2, 48 h after enrollment. MFI microvascular flow index, PMX-HP polymyxin B hemoperfusion, PPV proportion of perfused vessels, PVD perfused vessel density, TVD total vessel density. *p < 0.05 by intent-to-treat analysis using Mann–Whitney test

Discussion

The question addressed by the present study was whether PMX-HP treatment can improve microcirculation by removing endotoxin and reducing endotoxin-related microcirculatory dysfunction in patients with septic shock. The main finding of this study is that microcirculation in patients with septic shock was improved after PMX-HP treatment. We observed that TVD and PVD were higher in the patients received PMX-HP treatment than in those who received conventional treatment at 48 h after enrollment. However, no significant improvement was observed in the SOFA score, MAP, lactate level, and the total amount of fluid supplementation after PMX-HP treatment.

The finding of improved microcirculation after PMX-HP treatment for septic shock was compatible with the results of the rat sepsis model mentioned in Introduction [9]. Moreover, our previous septic shock pig study revealed that PMX-HP attenuated microcirculatory dysfunction at the ileal mucosa and kidney surface at 6 h after PMX-HP treatment [20]. However, no significant improvement was observed regarding sublingual microcirculation at 6 h after PMX-HP treatment in those pigs with septic shock. This observation indicated that different organ exhibited heterogeneity regarding the timing and severity of microcirculatory dysfunction. Compared with PVD in healthy volunteers in our previous study [3], PVD was 18% (95% confidence interval 10% to 25%) lower at T2 in the control group than in healthy volunteers, and PVD was 7% (95% confidence interval − 1% to 14%) lower, albeit nonsignificantly, at T2 in the PMX-HP group than in healthy volunteers. In addition, the mortality of septic shock in this study was relatively low, and the values of PVD in the two groups were compatible with the values of PVD in survivors with septic shock [3].

This study did not observe significant intergroup differences in the SOFA score, MAP, and lactate level. The reason for the lack of significant clinical benefits after PMX-HP treatment could be the low severity of septic shock with a relatively low mortality rate of 7% in our enrolled patients. The low mortality rate was compatible with the SOFA score prediction of mortality; an initial score of 9 and a 48-h score of 6 reflect mortality of less than 10% [21]. Notably, PMX-HP reduced mortality in septic shock patients with intermediate- (30–60%) and high-risks (> 60%) of mortality [22]. PMX-HP did not reduce mortality in septic shock patients with a low risk of mortality (< 30%) [22, 23]. Therefore, additional studies are required to investigate the effect of PMX-HP on microcirculation in patients with septic shock who have intermediate- and high-risks of mortality.

Our study did not show any adverse effects of PMX-HP treatment. Notably, the incidence of adverse events of PMX-HP treatment has been reported to be very low (< 1%), and the most commonly observed adverse effects of PMX-HP are thrombocytopenia, transient hypotension, and allergic reactions [24]. In our study, no significant intergroup difference was observed regarding the platelet count at T1 and T2. Moreover, PMX-HP was reported to remove inflammatory cells [25], but no significant intergroup difference was noted regarding the white blood cell count at T1 and T2.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study sample size was limited by the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Many patients did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded based on mild or severe severity of septic shock or a prolonged shock more than 24 h before enrollment. Second, surviving sepsis campaign guidelines have continually improved early resuscitation and survival of patients with septic shock. If patients are recognized early and adequately resuscitated in the emergency department or general ward, they may not need admission to ICUs or require the PMX-HP treatment. Because of the slow progress in recruiting participants after an extended enrollment for more than 4 years, we decided to stop the study before the target sample size was reached. Third, PMX-HP treatment requires heparin loading and infusion to prevent filter clotting, and the dose range of heparin was 1500 to 6000 IU at each session of PMX-HP. According to our heparin dosing protocol [15], no premature clotting session (< 90 min) or substantial bleeding event was observed in this study. However, heparin might prevent microthrombosis in small vessels and protect glycocalyx from shedding by suppressing inflammation [26]. The referenced dose of heparin was 12000 IU/day for 7 days in a randomized trial for the treatment of sepsis [27]. Hence, additional studies are warranted to investigate the effect of heparin on microcirculation in patients with septic shock. Fourth, the SDF video microscope required an experienced operator to obtain good quality images, and sometimes the enrollment of patients in this study was limited due to unavailability of experienced operators. We suggest that further groups of microcirculation study are encouraged to train their research staff to obtain and analyze the microcirculation images according to the two consensus of assessment of sublingual microcirculation [16, 19], and communicating with experienced groups of microcirculation study is helpful.

In conclusion, this preliminary study revealed that PMX-HP treatment improved microcirculation but not clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock at a low risk of mortality. Nevertheless, larger multicenter trials are required to confirm the effect of PMX-HP treatment on microcirculation and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock who have intermediate- and high-risks of mortality.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the regulation of the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- EAA:

-

Endotoxin activity assay

- ICU:

-

Intensive care units

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- MFI:

-

Microvascular flow index

- PaO2/FiO2 :

-

Arterial oxygen tension/fraction of inspired oxygen concentration

- PMX-HP:

-

Polymyxin B hemoperfusion

- PPV:

-

Proportion of perfused vessels

- PVD:

-

Perfused vessel density

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- TVD:

-

Total vessel density

References

De Backer D, Creteur J, Preiser JC, Dubois MJ, Vincent JL. Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):98–104.

Sakr Y, Dubois MJ, De Backer D, Creteur J, Vincent JL. Persistent microcirculatory alterations are associated with organ failure and death in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9):1825–31.

Shih CC, Liu CM, Chao A, Lee CT, Hsu YC, Yeh YC. Matched comparison of microcirculation between healthy volunteers and patients with sepsis. Asian J Anesthesiol. 2018;56(1):14–22.

Marx G, Vangerow B, Burczyk C, Gratz KF, Maassen N, Cobas Meyer M, et al. Evaluation of noninvasive determinants for capillary leakage syndrome in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(9):1252–8.

Bauer PR. Microvascular responses to sepsis: clinical significance. Pathophysiology. 2002;8(3):141–8.

Salomao R, Martins PS, Brunialti MK, Fernandes Mda L, Martos LS, Mendes ME, et al. TLR signaling pathway in patients with sepsis. Shock. 2008;30(Suppl 1):73–7.

Yeh YC, Ko WJ, Chan KC, Fan SZ, Tsai JC, Cheng YJ, et al. Effects of eritoran tetrasodium, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, on intestinal microcirculation in endotoxemic rats. Shock. 2012;37(5):556–61.

Cruz DN, Antonelli M, Fumagalli R, Foltran F, Brienza N, Donati A, et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in abdominal septic shock: the EUPHAS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(23):2445–52.

Iba T, Okamoto K, Kawasaki S, Nakarai E, Miyasho T. Effect of hemoperfusion using polymyxin B-immobilized fibers on non-shock rat sepsis model. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):755–61.

Ince C. Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Crit Care. 2015;19(Suppl 3):S8.

den Uil CA, Maat AP, Lagrand WK, van der Ent M, Jewbali LS, van Thiel RJ, et al. Mechanical circulatory support devices improve tissue perfusion in patients with end-stage heart failure or cardiogenic shock. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28(9):906–11.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637.

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552.

Lee CT, Chao A, Lai CH, Yeh YC. Heparin dosing score protocol for anticoagulation during polymyxin B hemoperfusion. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117(7):652–3.

Ince C, Boerma EC, Cecconi M, De Backer D, Shapiro NI, Duranteau J, et al. Second consensus on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation in critically ill patients: results from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(3):281–99.

Dobbe JG, Streekstra GJ, Atasever B, van Zijderveld R, Ince C. Measurement of functional microcirculatory geometry and velocity distributions using automated image analysis. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46(7):659–70.

Yeh YC, Lee CT, Wang CH, Tu YK, Lai CH, Wang YC, et al. Investigation of microcirculation in patients with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation life support. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):200.

De Backer DHS, Boerma C, Goedhart P, Buchele G, Ospina-Tascon G, Dobbe I, Ince C. How to evaluate the microcirculation: report of a round table conference. Crit Care. 2007;11(5):R101.

Yeh YC, Yu LC, Wu CY, Cheng YJ, Lee CT, Sun WZ, et al. Effects of endotoxin absorber hemoperfusion on microcirculation in septic pigs. J Surg Res. 2017;211:242–50.

Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1754–8.

Chang T, Tu YK, Lee CT, Chao A, Huang CH, Wang MJ, et al. Effects of polymyxin B hemoperfusion on mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a systemic review, meta-analysis update, and disease severity subgroup meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):e858–64.

Payen DM, Guilhot J, Launey Y, Lukaszewicz AC, Kaaki M, Veber B, et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in patients with septic shock due to peritonitis: a multicenter randomized control trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):975–84.

Ronco C, Klein DJ. Polymyxin B hemoperfusion: a mechanistic perspective. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):309.

Nishibori M, Takahashi HK, Katayama H, Mori S, Saito S, Iwagaki H, et al. Specific removal of monocytes from peripheral blood of septic patients by polymyxin B-immobilized filter column. Acta Med Okayama. 2009;63(1):65–9.

Li X, Ma X. The role of heparin in sepsis: much more than just an anticoagulant. Br J Haematol. 2017;179(3):389–98.

Jaimes F, De La Rosa G, Morales C, Fortich F, Arango C, Aguirre D, et al. Unfractioned heparin for treatment of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial (The HETRASE Study). Crit Care Med. 2009;37(4):1185–96.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the National Taiwan University Hospital Center of Microcirculation Medical Research (NCMMR). The extracorporeal hemoperfusion cartridges were supported by Toray Industries. They also thank Mr. Roger Lien (technician, MicroStar Instruments Co, Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan) for technical support in microcirculation analysis. This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Taiwan University Hospital (105-A125).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SHC contributed to the interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, and revision of the manuscript. WSC contributed to interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript. CML contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript and revision of the manuscript. CTC contributed to interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. AC contributed to the patient enrollment, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript. VCW contributed to the design of the study and revision of the manuscript. WHS contributed to the design of the study and revision of the manuscript. CHL contributed to patient enrollment and hemoperfusion. MJW contributed to the design of the study and revision of the manuscript. YCY contributed to the design of the study, patient enrollment, interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This prospective observational study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (approval number: 201208067RIB). Informed consents of the patients were obtained from their legally authorized representatives before enrollment in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that we have no competing interest in the authorship or publication of this contribution.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, SH., Chan, WS., Liu, CM. et al. Effects of endotoxin adsorber hemoperfusion on sublingual microcirculation in patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Intensive Care 10, 80 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00699-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00699-z