Abstract

Background

Utilization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has increased worldwide, but its use remains restricted to severely ill patients, and few referral centers are properly structured to offer this support. Inter-hospital transfer of patients on ECMO support can be life-threatening. In this study, we report a single-center experience and a systematic review of the available published data on complications and mortality associated with ECMO transportation.

Methods

We reported single-center data regarding complications and mortality associated with the transportation of patients on ECMO support. Additionally, we searched multiple databases for case series, observational studies, and randomized controlled trials regarding mortality of patients transferred on ECMO support. Results were analyzed independently for pediatric (under 12 years old) and adult populations. We pooled mortality rates using a random-effects model. Complications and transportation data were also described.

Results

A total of 38 manuscripts, including our series, were included in the final analysis, totaling 1481 patients transported on ECMO support. A total of 951 patients survived to hospital discharge. The pooled survival rates for adult and pediatric patients were 62% (95% CI 57–68) and 68% (95% CI 60–75), respectively. Two deaths occurred during patient transportation. No other complication resulting in adverse outcome was reported.

Conclusion

Using the available pooled data, we found that patient transfer to a referral institution while on ECMO support seems to be safe and adds no significant risk of mortality to ECMO patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) respiratory support is a potentially lifesaving strategy that has been shown to be cost-effective in high-income countries [1,2,3] and in a middle-income country [4]. Although its use remains restricted to cases of severe respiratory failure refractory to mechanical ventilation [5,6,7,8], further acute and chronic organ failures are very common and increase mortality and morbidity in these patients [9, 10]. Consequently, ECMO respiratory support is lifesaving only in highly select cases—namely, early after the onset of severe respiratory failure, and only in patients without severe acute or chronic organ dysfunctions [3, 5,6,7, 11, 12].

Facing the paucity of such cases, and the high level of expertise needed to implement ECMO support, a proper referral system becomes necessary and has been shown to be effective [7]. In the CESAR trial, the cost-effectiveness of ECMO respiratory support was demonstrated with 81% (73 out of 90) of ECMO-supported patients being transported to only one UK ECMO referral center [3]. However, the severity of those patients’ respiratory insufficiency makes transportation without ECMO support unsafe. Therefore, many referral centers transfer patients under ECMO respiratory support [13, 14] and, so far, there are no data regarding the safety of those inter-hospital ECMO transportations.

Considering the recent global increase in ECMO support, and the consequent increase in ECMO patient transportation, our objectives were the following: (a) to describe a Brazilian tertiary medical center’s experience with ECMO transportation of patients with severe respiratory failure, and (b) to describe the current literature by providing pooled results of mortality and complications associated with transportation on venovenous and venoarterial ECMO support.

Background

Patients of the Brazilian tertiary medical center

Patients’ data were retrieved from a prospectively collected REDCap database from the Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo [15]. From 2010 to 2014, physicians from various institutions directly contacted the Hospital das Clínicas ECMO team in cases of refractory hypoxemia. Initial evaluation was done through telephone contact together with a REDCap-based online form based on patients’ clinical and laboratory data [15]. The decision of whether or not to undertake the rescue was based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases of uncertainty, we required the consultation and approval of two other members of the ECMO team. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the clinical approach to support and ECMO initiation, were standardized and already published elsewhere [11, 16].

In all cases, cannulation was performed at bedside by the ECMO team at the consultant hospital. The femoral-to-internal jugular venovenous configuration was used. Bidimensional ultrasonography was used to guide the vascular puncture, guidewire insertion and cannulae positioning. A centrifugal magnetic pump with a Permanent Life Support (PLS) system using a polymethylpentene oxygenator (Rotaflow/Jostra Quadrox - D, Maquet CardiopulmonaryAG, Hirrlingen, Germany) was employed in all cases. Approximately 1 h after ECMO initiation, patients were transported in extracorporeal support to the Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo through ground ambulance or helicopter. The ECMO team for patient transportation consisted of 2 ICU physicians, 1 ICU nurse and 1 ICU respiratory therapist.

Systematic review of the literature

Registration

This systematic review, including its search protocol, was registered on the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42015024710).

Search strategy

We searched PUBMED (1966 until November 2012), EMBASE (January 1990 until November 2012), LILACS, and SCIELO to identify studies describing transportation of severely ill patients on ECMO support. Venovenous and venoarterial ECMO descriptions for respiratory support were included to better describe the population submitted to transportation while on ECMO. We relied upon observational studies, as no randomized studies comparing inter-hospital transportation of ECMO-supported patients have been published to date.

In order to enhance the sensitivity of our search, the terms were separated into two blocks for PUBMED, using medical subject headings [MeSH] and [All field] terms. The MeSH terms used in PUBMED were organized as follows: (“extracorporeal membrane oxygenation” or “extracorporeal oxygenation” or “extracorporeal life support” or ECMO) and (“transport” or “rescue work”). In the PUBMED, EMBASE, LILACS and SCIELO searches, the terms were inserted as [All fields] and were organized as follows: (“extracorporeal membrane oxygenation” or “extracorporeal oxygenation” or “extracorporeal life support” or ECMO) and (“transport” or “rescue work” or “rescue” or “retrieval”).

The resulting outputs were then combined. Duplicated results were excluded. The remaining articles were independently evaluated by 3 investigators (PVM, CAG and MP) for eligibility. Only manuscripts with the agreement of a least two investigators were included. We also searched personal records and the references of the retrieved articles for other potential studies.

Study evaluation and data extraction

Manuscripts were included only if data on patients’ transportation on ECMO support and hospital survival were available. Manuscripts involving animal data, case reports describing less than four subjects, language other than English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese and review articles were excluded. When available, the following data were also extracted: patients’ demographic features (including illness severity), mechanical ventilation information, complications during ECMO transportation, ECMO support data, and intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital lengths of stay. Retrieved data were also analyzed separately for pediatric patients and adult patients. When additional information was needed, an e-mail was sent to the main author requesting the data.

Quality assessment

Though there is no proper scoring system for evaluating case series of patients on ECMO support, we developed a predetermined system for all included studies based on previously published reports [17], and on commonly expected measures of quality for ECMO support and ECMO transportation. Each study was scored and a final grade was calculated to estimate data quality (Additional file). The studies’ final scores were classified by quality into three tertiles and mortality rate was assessed independently for each one of these groups.

Statistical analysis

Variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed, and median plus the 25th and 75th percentiles if otherwise. For descriptive data, a confidence interval was generated for each manuscript in accordance with the recommendations of the Association of Public Health Observatories (APHO) of England [18]. Some manuscripts did not present means and standard deviations for quantitative data. In these cases, means and standard deviations were estimated from the sample size, median, range or 25th and 75th percentiles, according to the Wan method [19]. Heterogeneity between and within studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic and Higgin’s I 2. Either a P < 0.10 or an I 2 > 50% was considered suggestive of significant heterogeneity. We a priori expected that studies would present high heterogeneity. Therefore, we performed a random-effects meta-analysis using the DerSimonian and Laird method for all pooled characteristics and effects. The analyses were done using the metafor package from R open-source software [20].

Results

Brazilian medical center

During the studied period, our group was called on for consultation for a total of 12 patients. Seven patients fulfilled the predefined criteria and were supported by ECMO. All patients had received at least one rescue maneuver for refractory hypoxemia before ECMO initiation, as described in Table 1. In all cases, patients were cannulated at the remote institution and transferred under ECMO support to Hospital das Clínicas. Data on respiratory failure etiology, laboratory data, and ECMO settings are described in Table 1. Five patients were successfully weaned from ECMO support. One patient died 21 days after ECMO removal due to septic shock. Median time on ECMO support was 5 days [2, 10]. ICU and Hospital length of stay were 13 [2, 20] and 20 days [2, 60], respectively. Four patients survived to hospital discharge and were still alive after 90 days, with a survival rate of 57%.

Individual characteristics of the Brazilian patients transported on ECMO support are described in Additional file 1: Table 1S. The median transfer distance was 31 km [1,163] with an average rescue mission time of 345 min [270,960]. In one case, an electrical failure of the pump battery caused an unexpected pump arrest and the need for manual rotation of the hand crank during ground ambulance transportation. No deaths or any severe ECMO complications occurred during transport to our institution.

Systematic review

Study inclusion

Our literature search yielded 610 publications for possible inclusion. Of these, 46 were excluded for duplicity. Of the remaining 564, 512 did not have data for hospital survival. Five studies required author contact for data clarification. Four authors responded to our solicitation and were included in the dataset. In the end, a total of 37 manuscripts were included for analysis (Additional file 2: Fig. 1S) [13, 14, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Three studies were considered to be low quality, and 34 were considered moderate to high quality by our scoring system (Additional file 3: Table 3S). Our case series was included in the final analysis, resulting in a total of 38 manuscripts.

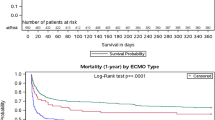

Outcomes

Mortality was assessed in all included studies for a total of 1481 patients. Of these, 1025 were adults, and 456 were pediatric. A total of 951 patients survived to hospital discharge after ECMO support in a crude analysis. The pooled survival rates for adult and pediatric patients were 62% (95% CI 57–68) and 68% (95% CI 60–75), respectively (Figs. 1, 2). After stratifying studies into tertiles of quality, we found a lower mortality rate in high-quality studies and a progressive increase in mortality for intermediary and lower tertiles. Mortality rates were 69% (95% CI 52–85%), 65% (95% CI 60–71%) and 61% (95% CI 46–76%) for the first, second and third tertiles, respectively. Total number of patients transported in each country is shown in Additional file 4: Figure 2s

General characteristics, pre-ECMO status, diagnosis and ECMO support data of the entire cohort are reported in Table 2. Most studies did not report any scoring system for hospital survival. Mean time on mechanical ventilation before ECMO initiation was 4.6 days (95% CI 3.7–5.5). Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome was the most prevalent diagnosis reported for adult patients, while meconium aspiration syndrome was the diagnosis most frequently reported for the pediatric population. ECMO support duration, ICU length of stay and hospital length of stay were 9.8 (95% CI 8.6–10.9), 22 (95% CI 15–30) and 32 (95% CI 25–28) days, respectively.

At least one complication was reported in 12 of the 38 manuscripts analyzed, totaling 80 occurrences in 1481 patients transported (Additional file 5: Table 2S). The most common complication was sudden fall in tidal volume during transportation. We found two reports of deaths during patient transportation to the referral institution. Rescue mission characteristics and adverse events are described in Table 3.

Discussion

ECMO remains a high-cost therapy with lifesaving potential in a select group of critically ill patients [3].Given the level of expertise needed for daily care of these patients, it is preferable that ECMO candidates be transferred to a specialized referral center. Because of the severe respiratory failure, patient transfer without ECMO is usually deemed to be too risky. Conversely, there are no data regarding the safety of inter-hospital ECMO transportations. Herein, we report a case series of patients transported under ECMO support to a referral hospital in Brazil with a survival rate of 57% and no major complications or deaths during transportation. Additionally, our systematic review of the literature showed a pooled survival rate for adult and pediatric patients of nearly two-thirds—with just 2 deaths reported in this cohort of 1481 patients—and without any other major adverse events resulting from the transportation itself.

Our data are compatible with the overall mortality reported in the latest publication by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO), in which the expected survival rate for adult venovenous extracorporeal support was 58% [56]. Similarly, using the available published data, we found a survival rate of 62% for adult patients transported while on ECMO. For the pediatric population, our pooled analysis retrieved a survival rate of 68%, in comparison with the 57% reported in ELSO guidelines [56]. Therefore, in this case series and in our overall analysis, we found no increase in mortality for ECMO support despite the need for patient transfer to a referral institution.

Concerns regarding the safety of transport of critically ill patients in need of extracorporeal support are an important question to be solved considering the recent global increase in ECMO support [5, 56, 57]. In the Cesar trial, patients who were randomized for the ECMO group were transferred to the referral center only after transport was considered safe by the ECMO Team, therefore delaying the initiation of support. As reported in the text, patients were not transported while on ECMO and, despite precautions, two deaths were reported during patient transfer [3]. Similarly, in a previous publication of 158 infants accepted for ECMO initiation, Boedy et al. reported 18 (39.1%) deaths associated with transport. Five infants died waiting for ECMO initiation and 13 died either during transport without ECMO assistance or, after arriving moribund, before ECMO could be started. Considering all these deaths occurred before ECMO initiation, the authors concluded that there may be a hidden mortality associated with ECMO transportation that is generally excluded when we look exclusively at ECMO-supported patients [58]. Therefore, a strategy of rapid ECMO initiation and patient transport while on ECMO support may be safer than the use of conventional mechanical ventilation during transfer to the referral center.

However, it is important to highlight that the presence of complications is common, and nearly a third of the analyzed studies reported at least one complication during transport. Sudden fall in tidal volume was the most common complication reported. Power failure, circuit rupture and other more severe complications were also reported, but no deaths or any adverse outcomes related to these complications during transport were described. It is interesting to note that the majority of complications (74%) were reported in one single study [43] (Additional file 5: Table 2s), suggesting that most reports on ECMO transportation did not focus on looking for adverse events. Certainly, the definition of complications during patient transportation varied between studies, making it difficult to understand the real size of this problem. It is very likely that the incidence of adverse events is much higher than described in this manuscript.

Our study has several limitations: (1) The absence of any scoring system in most of the studies makes it difficult to correlate expected mortality with final results. However, as previously described, overall mortality rate was compatible with the expected mortality previously published in the ELSO guidelines for ECMO-supported patients. (2) A publication bias may have affected our results. As observed in our analysis, low-quality studies were associated with a high mortality rate and, possibly, even higher mortality rates may be found in unpublished data. (3) No randomized clinical trial has directly evaluated the safety of transporting ECMO patients. Our data were extracted mainly from case series, and the results are limited by the inherent flaws of such studies. (4) The studies included in this manuscript span several years of ECMO transportation worldwide. Therefore, clinical and technical development, which may have influenced the presence of complications and death in ECMO patients throughout the years, are not addressed in this manuscript.

Conclusions

ECMO support is a high-cost therapy restricted to highly specialized referral centers. The analysis of pooled data from available literature suggests that patient transfer to a referral institution while on ECMO support seems to be safe and to not increase mortality in ECMO-supported patients. This modality should possibly be preferred over transport of such patients under conventional ventilation exclusively.

Abbreviations

- ECMO:

-

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

References

Petrou S, Edwards L. Cost effectiveness analysis of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation based on four year results from the UK Collaborative ECMO Trial. ArchDisChild Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(3):F263–8.

Schumacher RE, Roloff DW, Chapman R, Snedecor S, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in term newborns.A prospective cost-benefit analysis. ASAIO J. 1993;39(4):873–9.

Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1351–63.

Park M, Mendes PV, Zampieri FG, Azevedo LC, Costa EL, Antoniali F, et al. The economic effect of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to support adults with severe respiratory failure in Brazil: a hypothetical analysis. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2014;26(3):253–62.

Davies A, Jones D, Bailey M, Beca J, Bellomo R, Blackwell N, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for 2009 influenza A(H1N1) acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302(17):1888–95.

Pham T, Combes A, Rozé H, Chevret S, Mercat A, Roch A, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;187(3):276–85.

Noah MA, Peek GJ, Finney SJ, Griffiths MJ, Harrison DA, Grieve R, et al. Referral to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center and mortality among patients with severe 2009 influenza A(H1N1). JAMA. 2011;306(15):1659–68.

Brogan TV, Thiagarajan RR, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults with severe respiratory failure: a multi-center database. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2105–14.

Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Rozé H, Repesse X, Lebreton G, Luyt CE, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(10):1704–13.

Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, Hodgson C, Aubron C, Rycus PT, et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(11):1374–82.

Park M, Azevedo LC, Mendes PV, Carvalho CR, Amato MB, Schettino GP, et al. First-year experience of a Brazilian tertiary medical center in supporting severely ill patients using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(10):1157–63.

Wetsch WA, Spöhr FA, Hinkelbein J, Padosch SA. Emergency extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to treat massive aspiration during anaesthesia induction. A case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56(6):797–800.

Forrest P, Cheong JY, Vallely MP, Torzillo PJ, Hendel PN, Wilson MK, et al. International retrieval of adults on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(6):1082–5.

Forrest P, Ratchford J, Burns B, Herkes R, Jackson A, Plunkett B, et al. Retrieval of critically ill adults using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an Australian experience. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(5):824–30.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Azevedo LC, Park M, Costa EL, Santos EV, Hirota A, Taniguchi LU, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe hypoxemia: time for reappraisal? J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38(1):7–12.

Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies 2014 [Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/case_series.

Cunningham A, Fryers P, Abbas J, Flowers J, Stockton D. Technical Briefing 3: Commonly Used Public Health Statistics and their Confidence Intervals Public Health England Webpage2008 [Available from: http://www.apho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=48457].

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135.

Team RDC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2009. https://www.R-project.org/.

Bennett JB, Hill JG, Long WB, Bruhn PS, Haun MM, Parsons JA. Interhospital transport of the patient on extracorporeal cardiopulmonary support. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):107–11.

Rossaint R, Pappert D, Gerlach H, Lewandowski K, Keh D, Falke K. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for transport of hypoxaemic patients with severe ARDS. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(3):241–6.

Bulpa P, Evrard P, Dive A, Pranger D, Gonzales M, Installe E. Inter-hospital transportation of patients with severe acute respiratory failure on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):802.

Foley DS, Pranikoff T, Younger JG, Swaniker F, Hemmila MR, Remenapp RA, et al. A review of 100 patients transported on extracorporeal life support. ASAIO J. 2002;48(6):612–9.

Wagner K, Sangolt GK, Risnes I, Karlsen HM, Nilsen JE, Strand T, et al. Transportation of critically ill patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2008;23(2):101–6.

Haneya A, Philipp A, Foltan M, Mueller T, Camboni D, Rupprecht L, et al. Extracorporeal circulatory systems in the interhospital transfer of critically ill patients: experience of a single institution. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(2):110–4.

Arlt M, Philipp A, Zimmermann M, Voelkel S, Amann M, Bein T, et al. Emergency use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiopulmonary failure. Artif Organs. 2009;33(9):696–703.

Bessereau J, Chenaitia H, Michelet P, Roch A, Gariboldi V. Acute respiratory distress syndrome following 2009 H1N1 virus pandemic: when ECMO come to the patient bedside. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010;29(2):165–6.

Ciapetti M, Cianchi G, Zagli G, Greco C, Pasquini A, Spina R, et al. Feasibility of inter-hospital transportation using extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support of patients affected by severe swine-flu(H1N1)-related ARDS. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:32.

D’Ancona G, Capitanio G, Chiaramonte G, Serretta R, Turrisi M, Pilato M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator rescue and airborne transportation of patients with influenza A (H1N1) acute respiratory distress syndrome in a Mediterranean underserved area. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12(6):935–7.

Isgrò S, Patroniti N, Bombino M, Marcolin R, Zanella A, Milan M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for interhospital transfer of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: 5-year experience. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34(11):1052–60.

Chenaitia H, Massa H, Toesca R, Michelet P, Auffray JP, Gariboldi V. Mobile cardio-respiratory support in prehospital emergency medicine. Eur J Emerg Med. 2011;18(2):99–101.

Cianchi G, Bonizzoli M, Pasquini A, Bonacchi M, Zagli G, Ciapetti M, et al. Ventilatory and ECMO treatment of H1N1-induced severe respiratory failure: results of an Italian referral ECMO center. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:2.

Diaz Rodrigo. ECMO y ECMO mobile. Soporte Cardio Respiratorio Avanzado. 2011;22(3):377–87.

Javidfar J, Brodie D, Takayama H, Mongero L, Zwischenberger J, Sonett J, et al. Safe transport of critically ill adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support to a regional extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center. ASAIO J. 2011;57(5):421–5.

Bein T, Zonies D, Philipp A, Zimmermann M, Osborn EC, Allan PF, et al. Transportable extracorporeal lung support for rescue of severe respiratory failure in combat casualties. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1450–6.

Lebreton G, Sanchez B, Hennequin JL, Resière D, Hommel D, Léonard C, et al. The French airbridge for circulatory support in the Carribean. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15(3):420–5.

Haneya A, Philipp A, Foltan M, Camboni D, Müeller T, Bein T, et al. First experience with the new portable extracorporeal membrane oxygenation system Cardiohelp for severe respiratory failure in adults. Perfusion. 2012;27(2):150–5.

Roncon-Albuquerque R, Basílio C, Figueiredo P, Silva S, Mergulhão P, Alves C, et al. Portable miniaturized extracorporeal membrane oxygenation systems for H1N1-related severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a case series. J Crit Care. 2012;27(5):454–63.

Desebbe O, Rosamel P, Henaine R, Vergnat M, Farhat F, Dubien PY, et al. Interhospital transport with extracorporeal life support: results and perspectives after 5 years experience. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2013;32(4):225–30.

Lucchini A, De Felippis C, Elli S, Gariboldi R, Vimercati S, Tundo P, et al. Mobile ECMO team for inter-hospital transportation of patients with ARDS: a retrospective case series. Heart Lung Vessel. 2014;6(4):262–73.

Roch A, Hraiech S, Masson E, Grisoli D, Forel JM, Boucekine M, et al. Outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and brought to a referral center. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(1):74–83.

Broman LM, Holzgraefe B, Palmér K, Frenckner B. The Stockholm experience: interhospital transports on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2015;19:278.

Delnoij TS, Veldhuijzen G, Strauch U, Van Mook WN, Bergmans DC, Bouman EA, et al. Mobile respiratory rescue support by off-centre initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2015;30(3):255–9.

Raspé C, Rückert F, Metz D, Hofmann B, Neitzel T, Stiller M, et al. Inter-hospital transfer of ECMO-assisted patients with a portable miniaturized ECMO device: 4 years of experience. Perfusion. 2015;30(1):52–9.

Sherren PB, Shepherd SJ, Glover GW, Meadows CI, Langrish C, Ioannou N, et al. Capabilities of a mobile extracorporeal membrane oxygenation service for severe respiratory failure delivered by intensive care specialists. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(6):707–14.

Lindén V, Palmér K, Reinhard J, Westman R, Ehrén H, Granholm T, et al. Inter-hospital transportation of patients with severe acute respiratory failure on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation—national and international experience. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(10):1643–8.

Wilson BJ, Heiman HS, Butler TJ, Negaard KA, DiGeronimo R. A 16-year neonatal/pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation transport experience. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):189–93.

Coppola CP, Tyree M, Larry K, DiGeronimo R. A 22-year experience in global transport extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):46–52 (discussion).

Clement KC, Fiser RT, Fiser WP, Chipman CW, Taylor BJ, Heulitt MJ, et al. Single-institution experience with interhospital extracorporeal membrane oxygenation transport: a descriptive study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(4):509–13.

Cabrera AG, Prodhan P, Cleves MA, Fiser RT, Schmitz M, Fontenot E, et al. Interhospital transport of children requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for cardiac dysfunction. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6(3):202–8.

Vaja R, Chauhan I, Joshi V, Salmasi Y, Porter R, Faulkner G, et al. Five-year experience with mobile adult extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a tertiary referral center. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1195–8.

Rambaud J, Léger PL, Larroquet M, Amblard A, Lodé N, Guilbert J, et al. Transportation of children on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: one-year experience of the first neonatal and paediatric mobile ECMO team in the north of France. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):940–1.

Biscotti M, Agerstrand C, Abrams D, Ginsburg M, Sonett J, Mongero L, et al. One hundred transports on extracorporeal support to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(1):34–9 (discussion 9–40).

Bryner B, Cooley E, Copenhaver W, Brierley K, Teman N, Landis D, et al. Two decades’ experience with interfacility transport on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(4):1363–70.

Extracorporeal Life Suport Organization—ECLS Registry Report 2016. Available from: http://www.elso.org/Registry/Statistics/InternationalSummary.aspx.

Hinkelbein J, Spelten O, Mey C. High-quality logistical concept for interhospital transport is crucial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(27–28):485–6.

Boedy RF, Howell CG, Kanto WP. Hidden mortality rate associated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr. 1990;117(3):462–4.

Authors’ contributions

PVM, CAG and MP performed the statistical analysis, interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. ASH, RON, EVS, HYL and DJ contributed to the conception of the work, interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. BAMPB, ELVC and LCPA contributed to the conception of the work, interpretation of data and final critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Dr. Alberto Lucchini, Dr. Roberto Roncon-Albuquerque Jr., Dr. Alain Morris and Dr. Richard T. Fizer for providing additional data regarding their previously published manuscripts.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient information for this manuscript was retrospectively recovered from that database, without identification. Therefore, patient informed consent was waived by the Ethics in Human Research committee (Protocol Number 107.443).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mendes, P.V., de Albuquerque Gallo, C., Besen, B.A.M.P. et al. Transportation of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a tertiary medical center experience and systematic review of the literature. Ann. Intensive Care 7, 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0232-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0232-7