Abstract

Thyroid hormone (T3) has been suggested to participate in the regulation of herpesvirus replication during reactivation. Clinical observations and in vivo experiments suggest that T3 are involved in the suppression of herpes virus replication. In vitro, differentiated LNCaP cells, a human neuron-like cells, further resisted HSV-1 replication upon addition of T3. Previous studies indicate that T3 controlled the expression of several key viral genes via its nuclear receptors in differentiated LNCaP cells. Additional observation showed that differentiated LNCaP cells have active PI3K signaling and inhibitor LY294002 can reverse T3-mediated repression of viral replication. Active PI3K signaling has been linked to HSV-1 latency in neurons. The hypothesis is that, in addition to repressing viral gene transcription at the nuclear level, T3 may influence PI3K signaling to control HSV-1 replication in human neuron-like cells. We review the genomic and non-genomic regulatory roles of T3 by examining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway gene expression profile changes in differentiated LNCaP cells under the influence of hormone. The results indicated that 15 genes were down-regulated and 22 genes were up-regulated in T3-treated differentiated LNCaP cells in comparison to undifferentiated state. Of all these genes, casein kinase 2 (CK2), a key component to enhance PI3K signaling pathway, was significantly increased upon T3 treatment only while the cells were differentiated. Further studies revealed that CK2 inhibitors tetrabrominated cinnamic acid (TBCA) and 4, 5, 6, 7-tetrabromo-2H-benzotriazole (TBB) both reversed the T3-mediated repression of viral replication. Together these observations suggested a new approach to understanding the roles of T3 in the complicated regulation of HSV-1 replication during latency and reactivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The herpes viruses, herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex 2 (HSV-2) are infamous to the general public for causing unsightly and painful oral and genital lesions [1]. Curiously the third member of the alpha human herpes virus family (αHHV), human herpes virus 3, or varicella zoster virus (VZV), commonly known as the chicken pox or shingles virus, is considered less of a taboo. This is perhaps due to the success and ubiquity of the VZV vaccine in the late 1980s and that lesions from VZV rarely present themselves more than a few times in a patient’s life, usually during early childhood and late adulthood [2]. Conversely, HSV-1 and HSV-2 symptoms occur sporadically throughout the patient’s lifetime with little predictability. It is this alternating duality between symptomatic, lytic, and asymptomatic, latent, periods that led to the name herpes or creeping from Latin. In addition to having lytic and latent periods, these herpes viruses have similar virion structures, protein functionality, genetic similarity, cause epithelial lesions and the affinity to reside almost exclusively in sensory ganglion during latency. Ironically the biological mechanisms that determine when and how these viruses exit latency and produce lytic symptoms is still undefined. Researchers believe that a complex relationship between the host’s immune system, nervous system, infected cell signal transduction, infected cell transcriptional regulation, and stress from the host’s environment is responsible for the switch.

Interestingly thyroid hormones, play roles within the immune system, nervous system, cell signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, etc. and T3 fluctuations are often linked to environmental stress [1]. These associations led to the hypothesis that thyroid hormones play a role in the suppression and reactivation of herpes viruses. To test this hypothesis our lab has studied the effect of thyroid hormone treatments on HSV-1 infections using different models. In addition, our lab has reported results from two retrospective clinical data analyses where patients with thyroid hormone complications increased the odds ratio of having herpes virus reactivation [3, 4]. The first study identified that several specific age/gender hospitalized patient groups at a comprehensive research medical center in urban Taiwan, with thyroid disorders were 2 times more likely to also have a αHHV [4]. The second study identified that hospitalized patients at a regional hospital in rural Maryland with thyroid disorders were 3 times more likely to have VZV diagnoses [3]. To understand these clinical observations, our lab studies cellular thyroid hormone action in regards to transcriptional regulation and signal transduction and have found that both mechanisms might be affecting HSV-1 infections.

The nuclear activity of T3 and its receptor (TR) family has been studied for decades [5–22]. The most well characterized mechanisms involve the transcriptional regulation of genes that are transcriptionally repressed in the absence of T3 and activated upon ligand TR. Most these genes contain a T3 response element (TRE) within its promoter. The traditional TRE, known as a direct repeat 4 (DR4) is characterized by containing two hexameric half-sites, with a 5′-AGGTCA-3′ consensus sequence, separated by any 4 nucleotides. Typically, the TR DNA binding domain (DBD) binds to the downstream half-site with retinoic acid X receptor (RXR) occupying the upstream half-site, forming a heterodimer. TR homodimers are also reported. In the absence of T3, the complex either bind loosely allowing repressive histones to block transcription or the complex can participate in recruiting repressive histone modifying enzymes. Upon T3 binding to the TR the complex undergoes a conformational change which recruits transcription activating histone modifying enzymes. Other, less common, TRE arrangements such as single half-sites, inverted repeats (IR) and palindromes found on the TSHβ, lysozyme silencer, and TSHα genes (respectively) are not as well characterized. Epidermal growth factor receptor, myosin heavy chain β, prolactin, thyroid-stimulating hormone α, thyroid-stimulating hormone β, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, type II 5′-deiodinase and the HSV-1 TK promoter and impart a regulatory pattern seemingly opposite of the traditional DR4 TREspositive regulation [22–26]. When T3 is absent genes with these negative TRE (nTRE) are transcriptionally activated and upon T3 binding the transcription is repressed. These nTREs are found on the promoters of genes that well known to be repressed by T3 feedback inhibition.

T3 was also shown to influence PI3K signaling [27, 28]. In addition, the hormone exhibited non-genomic functions to control physiological functions. The actions were initiated by receptors at the plasma membrane or in the cytoplasm. The receptors mentioned in this category are either TR isoforms or integrin, for example, αvβ3 [29]. For example, TR is reported to interact with the Pi3K regulatory subunit Pi3KR1 resulting in increased Pi3K activity. Therefore, it appeared that T3/TR used many mechanisms to expand their regulatory roles in biology. However, it is still unclear regarding its molecular mechanisms.

Differentiated human LNCaP cells have been developed as a proxy of neurons for investigating the regulation of HSV-1 gene expression and replication [30–32]. This differentiated cell line is not a true sensory neuron of trigeminal ganglia or dorsal root ganglia where HSV-1 usually infected during latency, but demonstrated important human neuron-like morphology and physiology. The cells following differentiation exhibited long neurite-like processes, rounding of the cell body, the presence of secretory granules as well as physiological markers such as the expression of chromogranin-A, differentiation-specific ionic conductances, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and the secretion of mitogenic neuropeptides neurotensin, and parathyroid hormone-related peptide [33–36].

Herpes virus transcriptional regulation by TR and T3

Several decades old and our recent studies have explored the nTRE in the promoter of the HSV-1 thymidine kinase (TK) gene [37–39]. Initially this promoter was believed to be insensitive to treatments in most cells but activated in pituitary cells upon T3 [39]. More recently it has been shown that T3 can cause the repression of TK transcription in the certain neuron-like differentiated cell types that expresses the appropriate cofactors [32, 37]. These conditions mirror the only cellular environment where herpes virus latency exists, sensory neurons. In addition, our lab showed that T3 treatment of these infected differentiated neuron-like cells had markedly reduced HSV-1 replication compared to controls. The virus retained the ability to replicate normally after the T3 was removed from the system, mimicking latency and reactivation [32, 40]. Our observations however, puzzle our virologist colleagues since HSV-1 TK is not considered an essential gene to viral replication. Therefore, we continue to explore other mechanisms that support our findings. In a parallel we have tested the ability of T3 to repress the VZV nucleotide kinase (VZV-PK) in transfection experiments. Similarly, to transfection experiments with HSV-1 TK, VZV-PK promoter activity is also repressed by T3 treatment [3].

T3 signal transduction regulation

It has been realized that signaling pathway activated via PI3-kinase (PI3K) and Akt is necessary to repress HSV-1 reactivation [41]. Studies indicated that PI3K activation by nerve growth factor (NGF) interaction with its high-affinity tropomyosin receptor kinase (TrkA) generated a cascade of signals resulting in neuronal gene expression changes thus promoting latent infection. This observation was supported by a number of investigations showing that addition of anti-NGF antibodies to the explanted trigeminal ganglia (TG), superior cervical ganglia (SCG), and eyes of latently infected animals causing more virus shedding and increased reactivation [42]. Several downstream targets of PI3K/Akt pathway were discussed in terms of their functions in latency and reactivation. For instance, the mTORC1 kinase is one of the primary objects and it played a critical role in maintaining latency [43]. The mTORC1 was sufficient to regulate many proteins including eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which is a host cell translation repressor controlling cap-dependent mRNA translation and temporary disruption was sufficient to reactivate the virus [43]. Factors/episodes participating in altering PI3K/Akt pathway may have a role in modulating HSV-1 latency and reactivation but the detailed mechanisms were unclear.

Previous reports showed that without affecting cell viability T3 was sufficient to control HSV-1 gene expression and replication in human neuron-like cells by targeting key viral genes [1, 30–32, 37]. It is not known if the hormone influenced the PI3K/Akt cascaded to produce the regulation. Our ongoing study attempts to investigate the gene expression profile changes upon T3 treatment comparing differentiated and undifferentiated conditions. Several genes exhibited significant expression level changes, and function inhibition of one gene reversed T3-mediated repression and promoted viral replication.

HSV-1 infected murine trigeminal ganglion (TG) explant

To correlate our clinical findings with our molecular biology data and our hypothesis we performed a small animal experiment. Explanted TG from mice latently infected with HSV-1 treated with T3 exhibited delayed viral release compared to no treatment (Fig. 1A). Over the 8-day period post explant, samples from the two culture groups were analyzed by plaque assay for infectious viral particles (ivp). The untreated group began releasing measurable ivp at day 5 which increased over the remaining days of the experiment. The T3 treated sample did not release measurable particles until the 8th day, which were fourfold lower compared to the untreated explants (Fig. 1A).

A HSV-1 infectious viral particles (ivp) released from T3 treated latently infected mouse TG explants. TGs from mice n = 10 latently infected with HSV-1 were explanted 30 days post infection. TG explants were separated into replicates of two treatment groups, +T3 and −T3, and were cultured for 8 days post explant. Media from each replicate was quantitatively tested daily for HSV-1 ivp via plaque assay. Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis suggests that statistically significant differences in ivp between +T3 and −T3 treatment at days 6, 7, and 8. Asterisk denotes p < 0.001. B PI3K Pathway is active in differentiated LNCaP cells with pAkt increase in differentiated cells. Western blot was performed using rabbit monoclonal IgG antibody against phospho-AKT pSer473 (ThermoSci, Cat#: OMA-03061) and mouse antibody AKT (Rockland, Cat#: 200-301-401) at a dilution of 1:1000 followed by the addition of conjugated secondary antibody for detection on extract from undifferentiated and differentiated LNCaP cells. C PI3K inhibitor reversed T3-mediated repression HSV-1 viral replication from differentiated LNCaP cells treated with 100 nM T3 and/or 20 µM LY294002 (Sigma Aldrich, cat#: L9908) was measured quantitatively by FLICIT assays [68]. In short, Vero cells were seeded on 384-well plates followed by exposure to media from EGFP HSV-1 infected cultures. The infected media samples were applied in serial dilutions in replicates and were incubated for 8–18 h when EGFP was observed. The numbers of total cells and infected cells were imaged and quantified by the BioTek Cytation3 fluorescent imaging station and Gen5 software then used to calculate the viral titer using an inverse Poisson’s equation as previously described. Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis suggests that statistically significant differences in fluorescently labeled infected cells per mL exists. a p < 0.018, b p < 0.004, c p < 0.012, d p < 0.035

PI3K/Akt pathway is active in differentiated LNCaP cells and contributed to T3-mediated regulation of HSV-1 replication

Differentiated LNCaP cell is considered a human neuron-like cells due to its physiological similarity to neurons. We have developed a protocol (T3 removal assays) to measure the effects of hormone on neurotropic virus replication such as HSV-1 [32, 40]. In short, two groups of cells were infected under T3 for 48 h then the hormone was removed from one group and the T3 regulatory effects were measured by either plaque assays or FLICIT assays at 96 hpi [44]. It was speculated that PI3K/Akt signaling is active in differentiated LNCaP since it was very suppressive to HSV-1 replication in comparison to undifferentiated condition [32, 40]. This hypothesis was tested first by Western blot analyses using antibodies against total Akt and phospho Akt (pAkt) on extracts from undifferentiated and differentiated LNCaP cells. The results demonstrated that the level of pAkt was quite low if there was any in undifferentiated cells but significantly increased when cells were differentiated (Fig. 1B). The PI3K suppressive effects on HSV-1 replication was studied by inhibitor LY294002, which was shown to reactivate HSV-1 from latency by blocking PI3K pathway [41, 43, 45]. The results showed that LY294002 reversed T3-mediated repression (Fig. 1C). These observations together indicated that differentiation activated the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway of LNCaP cells and this activation participated in the T3-mediated repression of HSV-1 replication.

PI3K pathway related gene expression profiles of differentiated LNCaP under T3 treatment

To address the impact of T3 on the PI3K pathway in differentiated cells compared to undifferentiated conditions, we performed quantitative PrimePCR® PI3K-Akt Array Assays to measure the expression profile of PI3K related genes. 84 genes were analyzed (complete data in Additional file 1: Figure S1). Of all these genes, the expression of 15 genes were decreased and 22 genes were increased significantly in T3-treated differentiated LNCaP cells when compared to undifferentiated LNCaP (Fig. 2A). For example, eIF4E and its regulator eIF4EBP1 showed opposite expression profile (Fig. 2A). To be specific, eIF4E from differentiated cells was identified to have sevenfold expression increase in comparison to undifferentiated condition. eIF4EBP1, however, exhibited fivefold decrease. In addition, eIF2AK2, commonly known as PKR, reported to play a role in blocking HSV-1 translation, displayed a two-fold increase in T3-treated differentiated cells (Fig. 2A). Together the analyses suggested that PI3K gene expression was hugely influenced by T3 and may have critical roles in controlling viral replication in differentiated condition.

A Transcription profiles of genes involved in PI3K/Akt pathway measured by qRT-PCR arrays. Undifferentiated and 5-day differentiated LNCaP cells plated on poly-d-lysine coated T75 flasks were treated with and without 100 nM T3 for 48 h. The total RNA was purified by TRIZOL and the cDNA was synthesized using RT2 first strand kit (QIAGEN, cat#: 330401). For the transcriptome heatmaps assessment, the cDNA was subjected to qRT-PCR array analyses via PI3K-AKT signaling pathway (SAB Target List) H96 (BIO-RAD, cat#: 100-34223). The protocol was described essentially by the manufactures based on the CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD Cat# 1855200). Amplification was plotted and analyzed in triplicates using the BIO-RAD CFX manager software provided by the manufacturer. For each gene, the brightest red squares indicate at least a fourfold increase over the brightest blue square. A Showed the select genes from PI3K-AKT target list modulated significantly by T3 treatment and differentiation. Akt, EIF, and mTOR genes regulated by T3 and differentiation. B CK2 inhibitor TBB disrupts T3 mediated reduction of viral replication. The viral replication was measured by T3 removal assays [32] and FLICIT assays as shown in B with modification. TBB (Santa Cruz Bio, cat#: sc-202830) was added at 1 µM for CK2 inhibition. In short, differentiated cells were infected with HSV-1. At 48 hpi, infected cells were treated with (1) T3, (2) T3 washout, (3) T3 plus TBB, or (4) T3 washout plus TBB. The culture media were collected at 96 hpi and subjected to PLICIT assays. The results showed that infection with 100 nM of T3 reduced viral replication and hormone washout reversed this reduction. The addition of TBB disrupted the T3–mediated repression. FLICIT was reported previously [68] and described in the figure. Data in triplicates, two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis suggests that statistically significant differences in fluorescently labeled infected cells exists; a, b, c, d, e p < 0.001. C TBCA reversed T3-mediated suppression of viral replication in differentiated cells. LNCaP cells were infected under treatment of no T3, with T3, 110 nM TBCA (Millipore, cat#: 218710), or T3 + TBCA followed by plaque assays to measure the release of infectious viruses. No suppression of viral replication was observed for undifferentiated cells under the influence of T3 and/or TBCA when analyzed by ANOVA (data not shown). T3 removal assays as described in A were used to investigate the effects of TBCA. At 48 hpi, infected cells were treated with (1) T3, (2) T3 washout, (3) T3 plus TBCA, or (4) T3 washout plus TBCA. It is shown that TBCA, similar to TBB, reversed the suppression of viral replication by T3 as measured by viral plaque assay. Data in triplicates were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis suggests that statistically significant differences in pfu per mL exists; a p < 0.001, b p < 0.046, c p < 0.040

Roles of casein kinase 2 in HSV-1 replication in T3-treated differentiated LNCaP cells

Casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that targets a number of proteins such as casein [46]. The kinase is composed of a tetramer of α, α’, and two β subunits [47, 48]. The PrimePCR assays showed that casein kinase 2 α1 (CSNK2A1) was significantly upregulated in T3-treated differentiated LNCaP cells (Fig. 2A). It was shown that CK2 can promote PI3K/Akt signaling by inhibiting PTEN, a suppressor of Akt/PKB signaling pathway [49–54]. To test the hypothesis that TH promoted HSV-1 replication suppression in differentiated LNCaP by enhancing PI3K signaling via CK2, an inhibitor of CK2, TBB was first used in HSV-1 infection of differentiated LNCaP cells in the presence of T3. The results indicated that hormone was suppressive to the viral replication and removal of T3 at 96 hpi activated the viral replication repressed by T3, suggesting the experiment was valid (Fig. 2B). The TBB treatment somehow overturned the T3-mediated suppression (Fig. 2B). It is likely due to the blocking of the CK2 activity.

Although TBB is widely used as a CK2 inhibitor, it was reported to have more effects on other kinase [55–58]. To confirm the roles of CK2 in this T3-mediated HSV-1 replication regulation, a recently reported CK2 inhibitor, TBCA, was used since it exhibited more specific inhibition on CK2 [59, 60]. To distinguish the importance of differentiation, undifferentiated cells were infected in the presence of T3 with or without TBCA and the results demonstrated that there was no difference in terms of the strength of viral replication (data not shown). However, when the cells were differentiated, T3 repressed the viral replication and hormone washout at 96 hpi recovered the viral replication previously blocked by T3 (Fig. 2C). The TBCA treatment, like the TBB, abolished the T3-mediated suppression (Fig. 2C). Together these results supported the hypothesis that increased expression of CK2 by T3 may have a role in modulating PI3k/Akt pathway in differentiated human neuron-like cells to suppress HSV-1 replication.

Conclusions

Using this model, we were able to address the importance of differentiation during HSV-1 latency since the HSV-1 infection of undifferentiated LNCaP was very efficient and the differentiation significantly decreased the viral replication [31, 32, 40]. However, it is important to realize the limitations of this model. For example, it is a human neuroendocrine prostate cancer cell line and can only serve as an in vitro model without reflecting the real situations of latent infections. HSV-1 replication, although reduced dramatically, never established a bona fide latency in this model.

With these limitations in mind, this model has several advantages for HSV-1 study. First, it can be easily induced to differentiate simply by androgen deprivation [61] with consistent results and the differentiation is usually achieved within 2 weeks and the cells can survive in this condition for up to a month with normal culture condition without the addition of NGF. In addition, these infected cells when treated with T3 exhibit a marked reduction in HSV-1 replication and release. While not considered a gene essential to replication in lytic infections, HSV-1 TK transcription is substantially reduced upon T3 treatment [62]. TK has been referenced as one of the necessary genes for efficient reactivation in neurons since other genes are also expressed at the very beginning of the reactivation [63, 64]. This leads us to consider the transcriptional regulation of TK by T3, one of several factors in the control and switch between herpes latency and reactivation. We further hypothesize that other additional T3 mechanisms, such as PI3K signaling, also play a role in this complex switch.

While cytoplasmic TR acting with PI3K has been reported we have not yet explored this mechanism experimentally in our system. We plan to further investigate the roles of both genomic and nongenomic TR action using siRNA against key Pi3K, CK2, and TR subunits and isoforms. Currently our data supports that T3/TR viral suppression is due to genomic suppression of the viral genome and genomic regulation of CK2 and Pi3K pathway components which leads to additional nongenomic regulation. Furthermore, we have identified putative TREs on the promoter region of CK2 and plan to confirm them with a series of mutation experiments and electromobility shift assays.

The relationship between T3 and CK2 was not extensively investigated. Most studies showed that CK2 phosphorylated TR isoforms or corepressor [20, 65, 66]. Thyroid hormone was reported to enhance casein kinase activity in the liver of rat [67]. In our study, HSV-1 replication was retarded and inhibitors against CK2 was sufficient to rescue the virus’s ability to replicate at normal levels. Based on our clinical, in vivo, in vitro, and molecular biology observations, it is likely that both genomic and non-genomic effects of T3 play a role in the suppression of herpesvirus infection and potentially participate in the complex regulation of latency and reactivation.

Abbreviations

- HSV-1:

-

herpes simplex virus type-1

- T3 :

-

thyroid hormone

- TBCA:

-

tetrabrominated cinnamic acid

- TBB:

-

4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-2H-benzotriazole

- LY294002:

-

2-morpholin-4-yl-8-phenylchromen-4-one

- hpi:

-

hours post infection

- FLICIT:

-

fluorescently labeled infected cell inoculum titration

- moi:

-

multiplicity of infection

References

Hsia SC, Bedadala GR, Balish MD. Effects of thyroid hormone on HSV-1 gene regulation: implications in the control of viral latency and reactivation. Cell Biosci. 2011;1(1):24.

Kennedy PG. Issues in the Treatment of neurological conditions caused by reactivation of varicella zoster virus (VZV). Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(3):509–13.

Ajavon A, et al. Influence of thyroid hormone disruption on the incidence of shingles. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:1–15.

Hsia SH, Hsia SV. A cohort historical analysis of the relationship between thyroid hormone malady and alpha-human herpesvirus activation. J Steroids Horm Sci. 2014;5(2):133.

Abel ED, et al. Critical role for thyroid hormone receptor β2 in the regulation of paraventricular thyrotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(8):1017–23.

Bendik I, Pfahl M. Similar ligand-induced conformational changes of thyroid hormone receptors regulate homo- and heterodimeric functions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(7):3107–14.

Chatterjee VK, et al. Negative regulation of the thyroid-stimulating hormone alpha gene by thyroid hormone: receptor interaction adjacent to the TATA box. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(23):9114–8.

Chiamolera MI, Wondisford FE. Minireview: thyrotropin-releasing hormone and the thyroid hormone feedback mechanism. Endocrinology. 2009;150(3):1091–6.

Crone DE, Kim HS, Spindler SR. Alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptors bind immediately adjacent to the rat growth hormone gene TATA box in a negatively hormone-responsive promoter region. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(19):10851–6.

Darling DS, Burnside J, Chin WW. Binding of thyroid hormone receptors to the rat thyrotropin-beta gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3(9):1359–68.

Datta S, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor mediates transcriptional activation and repression of different promoters in vitro. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6(5):815–25.

Grontved L, et al. Transcriptional activation by the thyroid hormone receptor through ligand-dependent receptor recruitment and chromatin remodelling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7048.

McCabe CJ, et al. Differential regulation of the human thyrotropin alpha-subunit promoter by thyroid hormone receptors α1 and β1. Thyroid. 1998;8(7):601–8.

Muscat GE, et al. Characterization of the thyroid hormone response element in the skeletal alpha-actin gene: negative regulation of T3 receptor binding by the retinoid X receptor. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4(4):269–79.

Rentoumis A, et al. Negative and positive transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4(10):1522–31.

Shibusawa N, Hollenberg AN, Wondisford FE. Thyroid hormone receptor DNA binding is required for both positive and negative gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(2):732–8.

Tagami T, Park Y, Jameson JL. Mechanisms that mediate negative regulation of the thyroid-stimulating hormone alpha gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22345–53.

Wulf A, et al. The role of thyroid hormone receptor DNA binding in negative thyroid hormone-mediated gene transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41(1):25–34.

Xu J, et al. T3 receptor suppression of Sp1-dependent transcription from the epidermal growth factor receptor promoter via overlapping DNA-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(21):16065–73.

Zhou Y, et al. The SMRT corepressor is a target of phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2 (casein kinase II). Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;220(1–2):1–13.

Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14(2):184–93.

Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(3):1097–142.

Chen Y, Young MA. Structure of a thyroid hormone receptor DNA-binding domain homodimer bound to an inverted palindrome DNA response element. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(8):1650–64.

Zavacki AM, et al. Structural features of thyroid hormone response elements that increase susceptibility to inhibition by an RTH mutant thyroid hormone receptor. Endocrinology. 1996;137(7):2833–41.

Tini M, et al. An everted repeat mediates retinoic acid induction of the gamma F-crystallin gene: evidence of a direct role for retinoids in lens development. Genes Dev. 1993;7(2):295–307.

Yen PM, Sinha R. Cellular action of thyroid hormone, in endotext. In: De Groot LJ, editor. South Dartmouth; 2000.

Martin NP, et al. A rapid cytoplasmic mechanism for PI3 kinase regulation by the nuclear thyroid hormone receptor, TRβ, and genetic evidence for its role in the maturation of mouse hippocampal synapses in vivo. Endocrinology. 2014;155(9):3713–24.

Hiroi Y, et al. Rapid nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(38):14104–9.

Davis PJ, Goglia F, Leonard JL. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(2):111–21.

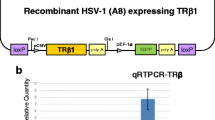

Chen F, et al. Overexpression of thyroid hormone receptor beta1 altered thyroid hormone-mediated regulation of herpes simplex virus-1 replication in differentiated cells. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(5):555–63.

Chen F, et al. A novel thyroid hormone mediated regulation of HSV-1 gene expression and replication is Specific to neuronal cells and associated with disruption of chromatin condensation. SOJ Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;1(1):1–7.

Figliozzi RW, et al. Thyroid hormone-dependent epigenetic suppression of herpes simplex virus-1 gene expression and viral replication in differentiated neuroendocrine cells. J Neurol Sci. 2014;346(1–2):164–73.

Mori S, Murakami-Mori K, Bonavida B. Oncostatin M (OM) promotes the growth of DU 145 human prostate cancer cells, but not PC-3 or LNCaP, through the signaling of the OM specific receptor. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(2A):1011–5.

Mori S, Murakami-Mori K, Bonavida B. Interleukin-6 induces G1 arrest through induction of p27(Kip1), a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, and neuron-like morphology in LNCaP prostate tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257(2):609–14.

Mariot P, et al. Overexpression of an alpha 1H (Cav3.2) T-type calcium channel during neuroendocrine differentiation of human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(13):10824–33.

Prevarskaya N, et al. Ion channels in death and differentiation of prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(7):1295–304.

Hsia SC, et al. Regulation of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase gene expression by thyroid hormone receptor in cultured neuronal cells. J Neurovirol. 2010;16(1):13–24.

Maia AL, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Is there a negative TRE in the luciferase reporter cDNA? Thyroid. 1996;6(4):325–8.

Park HY, et al. The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene promoter contains a novel thyroid hormone response element. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7(3):319–30.

Chen F, et al. Overexpression of thyroid hormone receptor β1 altered thyroid hormone-mediated regulation of herpes simplex virus-1 replication in differentiated cells. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:555–63.

Camarena V, et al. Nature and duration of growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases regulates HSV-1 latency in neurons. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(4):320–30.

Hill JM, et al. Nerve growth factor antibody stimulates reactivation of ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 in latently infected rabbits. J Neurovirol. 1997;3(3):206–11.

Kobayashi M, et al. Control of viral latency in neurons by axonal mTOR signaling and the 4E-BP translation repressor. Genes Dev. 2012;26(14):1527–32.

Figliozzi RW, et al. Using the inverse Poisson distribution to calculate multiplicity of infection and viral replication by a high-throughput fluorescent imaging system. Virol Sin. 2016;31(2):180–3.

Kobayashi M, et al. A primary neuron culture system for the study of herpes simplex virus latency and reactivation. J Vis Exp. 2012;62:1–6.

Montenarh M. Cellular regulators of protein kinase CK2. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;342(2):139–46.

Venerando A, et al. Isoform specific phosphorylation of p53 by protein kinase CK1. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(7):1105–18.

Cozza G, Bortolato A, Moro S. How druggable is protein kinase CK2? Med Res Rev. 2010;30(3):419–62.

Morotti A, et al. BCR-ABL inactivates cytosolic PTEN through casein kinase II mediated tail phosphorylation. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(7):973–9.

Gomes AM, et al. Adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells display decreased PTEN activity and constitutive hyperactivation of PI3K/Akt pathway despite high PTEN protein levels. Haematologica. 2014;99(6):1062–8.

Patsoukis N, et al. PD-1 increases PTEN phosphatase activity while decreasing PTEN protein stability by inhibiting casein kinase 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(16):3091–8.

Barata JT. The impact of PTEN regulation by CK2 on PI3K-dependent signaling and leukemia cell survival. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2011;51(1):37–49.

Martins LR, et al. Targeting CK2 overexpression and hyperactivation as a novel therapeutic tool in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116(15):2724–31.

Silva A, et al. PTEN posttranslational inactivation and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway sustain primary T cell leukemia viability. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3762–74.

Leung KK, Shilton BH. Quinone reductase 2 is an adventitious target of protein kinase CK2 inhibitors TBBz (TBI) and DMAT. Biochemistry. 2015;54(1):47–59.

Isaeva AR, Mitev VI. The protein kinase CK2 inhibitor TBB mediates up-regulation of MEK3/6 and p38delta activities, down-regulation of ERK1/2 activity and induction of G1/S arrest in normal human epidermal autocrine proliferating keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63(2):124–6.

Tapia JC, et al. Casein kinase 2 (CK2) increases survivin expression via enhanced beta-catenin-T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor-dependent transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(41):15079–84.

Smith MC, et al. CK2 inhibitors increase the sensitivity of HSV-1 to interferon-beta. Antivir Res. 2011;91(3):259–66.

Ryu SY, Kim S. Evaluation of CK2 inhibitor (E)-3-(2,3,4,5-tetrabromophenyl)acrylic acid (TBCA) in regulation of platelet function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;720(1–3):391–400.

Pagano MA, et al. Tetrabromocinnamic acid (TBCA) and related compounds represent a new class of specific protein kinase CK2 inhibitors. Chembiochem. 2007;8(1):129–39.

Klocker H, et al. Mechanism of androgen receptor activation and possible implications for chemoprevention trials. Eur Urol. 1999;35(5–6):413–9.

Tal-Singer R, et al. Gene expression during reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 from latency in the peripheral nervous system is different from that during lytic infection of tissue cultures. J Virol. 1997;71(7):5268–76.

Kosz-Vnenchak M, et al. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993;67(9):5383–93.

Pesola JM, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 immediate-early and early gene expression during reactivation from latency under conditions that prevent infectious virus production. J Virol. 2005;79(23):14516–25.

Katz D, Reginato MJ, Lazar MA. Functional regulation of thyroid hormone receptor variant TR alpha 2 by phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2341–8.

Glineur C, Bailly M, Ghysdael J. The c-erbA alpha-encoded thyroid hormone receptor is phosphorylated in its amino terminal domain by casein kinase II. Oncogene. 1989;4(10):1247–54.

Nakamura H, Rue PA, DeGroot LJ. Thyroid hormone increases type I adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase and casein kinase activities in rat liver cytosol: analysis of protein kinases by polyacrylamide disc gel electrophoresis. Endocrinology. 1983;112(4):1427–33.

Figliozzi RW, et al. Using the inverse Poisson distribution to calculate multiplicity of infection and viral replication by a high-throughput fluorescent imaging system. Virol Sin. 2016;31:180.

Authors’ contributions

RWF and FC participated in the design of the study and performed the experiments. RWF carried out the statistical analysis. SVH proposed the hypotheses and planned the study. RWF, FC, and SVH participated in the data interpretation and coordination and helped to write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported in part by NIH Grant R01NS081109 to SVH and the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS/NIH. The authors appreciate the editorial assistance from UMES staff.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

13578_2017_140_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Figure S1. BIO-RAD PrimePCR, qRT-PCR array, human PI3K-AKT signaling pathway (SAB target list) H96. Complete 84 gene expression heatmap. See main text for assay details.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Figliozzi, R.W., Chen, F. & Hsia, S.V. New insights on thyroid hormone mediated regulation of herpesvirus infections. Cell Biosci 7, 13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-017-0140-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-017-0140-z