Abstract

Background

Solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a rare soft tissue sarcoma with a low metastatic potential. A higher metastatic rate is observed in the high-grade/dedifferentiated variant. The most common expected site of distant spread are the lungs and the liver. Bone involvement is generally viewed as a late stage of disease spread. We report on a retrospective series of SFT patients relapsing with a single distant bone recurrence as first metastatic event, without evidence of other organ involvement.

Case presentation

All patients affected by a single distant bone metastasis from SFT as first distant event, without any evidence of other site of metastasis, observed at our Institution, were considered. Bone involvement from SFT was pathologically assessed in all cases and confirmed by expert pathologists. A total of six patients were retrospectively identified. Primary tumour arose from the meninges in four patients, from soft tissues in two. Bone metastases were located to the vertebrae, the hip, the acetabulum and the rib. In all cases, bone relapse was the first event, with one patient presenting a local relapse. Median time from the primary tumour and the evidence of bone relapse was 40 months (range 0–58). In 2/6 patients bone metastasis was treated with radiotherapy (RT), in 2/6 with surgery, in 2/6 with surgery plus RT. At a median follow-up of 55 months (range 23–88), 5/6 patients are alive (2/5 without disease, 3/5 with multicentric metastatic disease) and one is dead of disease. 2/6 patients did not relapse after the treatment of the bone metastasis.

Conclusions

This small series in a relatively rare histology suggests that isolated, possibly late, bone metastases are a plausible scenario, in particular in meningeal SFT. Notably, new bone lesions in a patient with a history of SFT should be always investigated. Exclusive local treatments may be an option, though collection of such series would be needed to define the best treatment strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a very rare sarcoma, most frequently occurring in middle-aged patients. SFT can occur in several anatomic sites like meninges, peritoneum, head and neck, extremities, and viscera [1–3]. Recently also primary SFTs arising from the bone have been reported [4]. SFT is characterized by a specific NAB2–STAT6 gene fusion which is responsible for the nuclear expression of the chimeric oncoprotein STAT6, which is the immunohistochemical hallmark of SFT [5–8] and helps in differential diagnosis. Of note, dedifferentiated SFT may lose the protein expression while retaining the fusion gene [9]. SFTs are known for the low tendency of recurrence and the low metastatic potential after complete resection (10–15 %), even if a higher metastatic rate (40 %) has been described in case of pleomorphic/dedifferentiated SFT [10, 11]. Recurrence may happen many years after the initial diagnosis [12]. As for all other sarcomas, the most frequent and initial site of metastasis is the lung, followed by the liver [13]. Bone involvement is reported in the late phase of the disease, in patients already affected by lung lesions [12].

We report on a retrospective series of SFT patients who suffered from a single distant bone recurrence as their first metastatic event, without evidence of any other organ involvement.

Case presentation

From May 2014 to April 2016 at the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori Milan, Italy, we observed five patients with a diagnosis of SFT relapsed with single bone metastasis plus an additional case whose bone metastasis was synchronous to the primary tumour.

Bone involvement from SFT was pathologically assessed in all cases and final diagnosis of bone relapse from SFT was confirmed by expert pathologists basing on morphologic and immunohistochemical features, with STAT6 nuclear immunopositivity, and by comparing the metastatic tissue with the primary tumour.

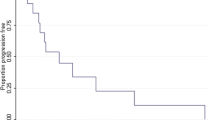

Disease status was assessed in all the patients by whole body CT scan, MRI and/or CT of the primary tumour site. A bone scan ruled out the presence of other metastatic bone lesions (Fig. 1).

Single bone metastasis from meningeal SFT (patient 1 in Table 1): CT scan (venous phase after contrast medium) shows a solid lesion characterized by homogeneous contrast enhancement at the level of the seventh left rib

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Primary SFT arose from the meninges in four patients, while in the soft tissues of the left thigh and left gluteus in two. Pathological centralized review of the primary tumour confirmed a diagnosis of malignant SFT in all the cases but one that was consistent with a classic SFT. The bone lesions were all consistent with a diagnosis of malignant SFT, with evidence of progression from a classic SFT towards a malignant SFT in one (Figs. 2,3).

Histopathological pattern of primary meningeal malignant SFT (patient 3 Table 1). Tumour shows patternless growth of a uniform, bland, hypercellular, STAT6 positive, spindle cell proliferation around characteristic thin walled branched vessel. STAT6 200×

Histopathological pattern of hipbone metastasis from primary meningeal malignant SFT (patient 3 Table 1). Similarly to primary lesion, tumour growths with patternless architecture, around thin walled vessel, with a more loose stroma, retaining immunoreactivity for STAT6. STAT6 200×

Bone metastases were mainly detected by the clinical complaint of pain, since a bone scan was not foreseen in the follow-up plan of these patients. Median time from the primary tumour diagnosis and the evidence of bone relapse was 40 months (range 0–58). In five cases, bone relapse was the first event while one patient presented with a synchronous single bone lesion (case 6 in Table 1).

All the patients received a definitive treatment of the bone lesion, with curative intent. A complete surgical resection of the bone metastasis was performed in four cases, followed by complementary radiotherapy in two cases. Radiotherapy was given in two cases.

At a median follow-up of 55 months (range 23–88), five of six patients are alive (2/5 without disease, 3/5 with multicentric metastatic disease) and one is dead of disease. Two of six patients (one treated with definitive RT and one with surgery plus RT) did not suffer of any tumour relapse after the treatment of the bone metastasis, at a follow-up of 51 and 56 months (Table 1).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis reports on a series of six patients affected by a single solitary bone metastasis from SFT as first metastatic event. This small series in a relatively rare histology shows that isolated, possibly late, bone metastases are a plausible scenario, in particular in meningeal SFTs.

All patients were treated with a curative intent. Two of them are still disease free at 51 and 56 months.

In the literature, the most common sites of metastasis in SFT patients were reported to be the lung and the liver [12, 14–31]. In addition, there are few case reports of SFTs, mostly arising from the meninges and pleura, presenting with multiple late distant bone metastases that followed the prior evidence of lesions located to the lung and to the liver. To our knowledge there are only two reports of SFTs relapsed with a single late bone metastasis and no extra-skeletal [32, 33]. Notably in both cases primary tumour was located to the meninges.

Our study confirms that isolated bone metastasis can occur in SFT. To note, in our series, in two of four cases the primitive tumour arose from the soft tissue.

Recently also primary SFT arising from the bone have been reported [26]. In case of a single bone lesion consistent with SFT a past or present primary tumour needs always to be ruled out.

In our series, median time from the primary tumour and the appearance of bone relapse was about 3 years, while published cases are reported after a long interval from the primary [32, 33].

All our patients received a local treatment of the bone metastasis with a curative intent. This could be considered an overtreatment as the standard of care of bone metastasis is offered with a palliative intent. Curative surgery was selected in four patients, followed by complementary radiotherapy in two cases (cases 3, 4, Table 1), while radiotherapy was given in two cases. However, it is interesting to note that in two cases with a prolonged follow-up the tumour has not yet relapsed. Yet to be confirmed on a larger prospective series, this suggests that in case of single bone metastasis a local treatment with curative intent may be an option.

In addition, in one of the two cases, the selected treatment was definitive RT alone suggesting that radiation treatment can be an alternative to surgery when morbidity is an issue. No patients received a systemic treatment for the single bone lesion; chemotherapy was given later in two patients who relapsed to multiple sites. SFTs show a low sensitivity to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy [34, 35]. Recently, systemic therapy has focused on molecularly targeted therapies reporting some activity of antiangiogenics (bevacizumab in combination with temozolomide, sorafenib, sunitinib and pazopanib) [35–37].

There is no consensus on the optimal routine follow-up policy of sarcomas [38]; although SFTs presenting with a single bone metastasis seem to be relatively rare, this series suggests that a bone scan should be included in the staging of SFT patients and in case of bone pain in a patient with a history of SFT.

In one case we observed a bone lesion progressing towards a more aggressive variant of SFT. This underlies once more the limits of the classification available to date [39]. None of our cases showed, at the time of the skeletal progression, a biological shift towards a high-grade dedifferentiated SFT. However, some of the cases showed an initial loss of STAT6 nuclear positivity in the bone metastasis, suggestive for a more aggressive potential. It is now described in the literature that immunohistochemical positivity for STAT6 may be lost in some SFTs while the fusion NAB2–STAT6 is retained [9]. To rule-out SFT diagnosis in these cases the demonstration of translocation is needed.

Conclusion

This small series in a rare sarcoma subtype suggests that isolated, skeletal metastases are a possible event in both meningeal and extrameningeal SFTs. On this basis bone lesions or symptoms in a patient with a history of SFT should be always investigated. Potentially curative local treatments may be an option, although a larger series is needed to define the best treatment strategy for such patients.

Abbreviations

- SFT:

-

solitary fibrous tumour

- CT scan:

-

computerized tomography

- MRI scan:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- RT:

-

radiotherapy

- CT:

-

chemotherapy

- IH:

-

immunohistochemistry

- NA:

-

not applicable

- M:

-

months

- Met:

-

metastasis

- Pos:

-

nuclear positivity

- *:

-

negativity of isolated neoplastic cells

- NED:

-

no evidence of disease

- AWD:

-

alive with disease

- DOD:

-

died of disease

- OS:

-

overall survival

References

Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385–6.

Bikmaz K, Cosar M, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, et al. Recurrent solitary fibrous tumour in the cerebellopontine angle. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:829–32.

Chan JKC. Solitary fibrous tumour—everywhere, and a diagnosis in vogue. Histopathology. 1997;31:568–76.

Verbeke SLJ, Christopher CDM, Path FRC, et al. A reappraisal of hemangiopericytoma of bone; analysis of cases reclassified as synovial sarcoma and solitary fibrous tumor of Bone. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:777–83.

Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2–STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet. 2013;45:131–2.

Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2–STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet. 2013;45:180–5.

Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, et al. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:390–5.

Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M, et al. STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:552–9.

Dagrada GP, Spagnuolo RD, Mauro V, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors: loss of chimeric protein expression and genomic instability mark dedifferentiation. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(8):1074–83.

Magro G, Emmanuele C, Lopes M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney with sarcomatous overgrowth. Case report and review of the literature. Apmis. 2008;116(11):1020–5.

Beadle GF, Hillcaot BL. Treatment of advanced malignant hemangiopericytoma with combination adriamycin and DTIC: a report of four cases. J Surg Oncol. 1983;22:167–70.

Baldi GG, Stacchiotti S, Mauro V, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of all sites: outcome of late recurrences in 14 patients. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2013;3:4.

The ESMO/European sarcoma network working group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):13–23.

Guillerme F, Truntzer P, Prim N, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors: case report of a late relapse. Cancer Radiother. 2011;15:330–3.

Park CK, Lee DH, Park JY, et al. Multiple recurrent malignant solitary fibrous tumors: long-term follow-up of 24 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1285–8.

Mohamed H, Mandal AK. Natural history of multifocal solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: a 25-year follow-up report. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:659–62.

Tzelepi V, Zolota V, Batistatou A, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the urinary bladder: report of a case with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11:101–6.

Fujita I, Kiyama T, Chou K, et al. A case of metastatic hemangiopericytoma occurring 16 years after initial presentation: with special reference to the clinical behavior and treatment of metastatic hemangiopericytoma. J Nihon Med Sch. 2009;76:221–5.

Hiraki A, Murakami T, Aoe K, Matsuda E, et al. Recurrent superior mediastinal primary hemangiopericytoma 23 years after the complete initial excision: a case report. Acta Med Okayama. 2006;60:197–200.

Suzuki H, Haga Y, Oguro K, et al. Intracranial hemangiopericytoma with extracranial metastasis occurring after 22 years. Neurol Med Chir. 2002;42:297–300.

Han N, Kim H, Min SK, et al. Meningeal solitary fibrous tumors with delayed extracranial metastasis. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50(2):113–21.

Someya M, Sakata KI, Oouchi A, Nagakura H, Satoh M, Hareyama M. Four cases of meningeal hemangiopericytoma treated with sur-gery and radiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:548–52.

Dufour H, Métellus P, Fuentes S, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericy-toma: a retrospective study of 21 patients with special review of postoperative external radiotherapy. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:756–62.

Pistolesi S, Fontanini G, Barellini L, et al. Meningeal hemangioperi-cytoma metastatic to the adrenal gland with multiple metastases to bones and lungs: a case report. Tumori. 2004;90:147–50.

Chang CC, Chang YY, Lui CC, Huang CC, Liu JS. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma with delayed multiple distant metastases. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:527–32.

Ambrosini-Spaltro A, Eusebi V. Meningeal hemangiopericytomas and hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumors of extracranial soft tissues: a comparison. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:343–54.

Mena H, Jorge L, Gholam H, et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the central nervous system; a review of 94 cases. Hum Pathol. 1991;21:84–91.

Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: histopathological features, treatment, and long-term follow-up of 44 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:514–22.

Mahmood A, Caccamo DV, Tomecek FJ, et al. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: a clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:955–63.

Prakasha B, Jacob R, Dawson A, et al. Haemangiopericytoma diagnosed from a metastasis 11 years after surgery for “atypical meningioma”. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:856–8.

Wu Z, Yang H, Weng D, et al. Rapid recurrence and bilateral lungs, multiple bone metastasis of malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the right occipital lobe: report of a case and review. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:91.

Nakada S, Minato H, Takegami T, et al. NAB2–STAT6 fusion gene analysis in two cases of meningeal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma with late distant metastases. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015;32:268–74.

Hoshi M, Araki N, Naka N, et al. Bone metastasis of intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:208–13.

Stacchiotti S, Libertini M, Negri T, et al. Response to chemotherapy of solitary fibrous tumour: a retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(10):2376–83.

Colia V, Provenzano S, Hindi N, et al. Systemic therapy for selected skull base sarcomas: chondrosarcoma, chordoma, giant cell tumour and solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21(4):361–9.

Stacchiotti S, Negri T, Palassini E, et al. Sunitinib malate and figitumumab in solitary fibrous tumor: patterns and molecular bases of tumor response. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(5):1286–97.

Park MS, Patel SR, Ludwig JA, et al. Activity of temozolomide and bevacizumab in the treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, and metastatic hemangiopericytoma and malignant solitary fibrous tumor. Cancer. 2011;117(21):4939–47.

ESMO/European sarcoma network working group. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):102–12.

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn P, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Pathology and genetics. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013.

Authors’ contributions

VC and SP compiled the clinical data, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. CM provided radiological data. SLR, PC and APDT provided the pathologic data. AM reviewed and edited the manuscript. PGC offered conceptual advice, reviewed and edited the manuscript. SS compiled the clinical data, offered conceptual advice, guided the composition process, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and supporting materials

The authors are happy to share their data for research purpose. Please contact the corresponding author in case.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Colia, V., Provenzano, S., Morosi, C. et al. Solitary fibrous tumour presenting with a single bone metastasis: report of six cases and literature review. Clin Sarcoma Res 6, 16 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13569-016-0055-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13569-016-0055-1