Abstract

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) can finely control the expression of target genes at the posttranscriptional level in prokaryotes. Regulatory small RNAs (sRNAs) designed to control target gene expression for applications in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology have been successfully developed and used. However, the effect on the heterologous expression of species- or strain-specific ncRNAs in other bacterial strains remains poorly understood. In this work, a Pseudomonas stutzeri species-specific regulatory ncRNA, NfiS, which has been shown to play an important role in the response to oxidative stress as well as osmotic stress in P. stutzeri A1501, was cloned and transferred to the Escherichia coli strain Trans10. Recombinant NfiS-expressing E. coli, namely, Trans10-nfiS, exhibited significant enhancement of tolerance to oxidative stress. To map the possible gene regulatory networks mediated by NfiS in E. coli under oxidative stress, a microarray assay was performed to delineate the transcriptomic differences between Trans10-nfiS and wild-type E. coli under H2O2 shock treatment conditions. In all, 1184 genes were found to be significantly altered, and these genes were divided into mainly five functional categories: stress response, regulation, metabolism related, transport or membrane protein and unknown function. Our results suggest that the P. stutzeri species-specific ncRNA NfiS acts as a regulator that integrates adaptation to H2O2 with other cellular stress responses and helps protect E. coli cells against oxidative damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By base pairing with target sequences within mRNA or proteins, noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in bacteria, also known as small RNAs (sRNAs), can modulate gene expression mainly at the posttranscriptional level (Wassarman et al. 1999). The macromolecules that interact with sRNAs were found to be involved in the regulation of a variety of biological processes, such as stress response, virulence, motility, biofilm formation, nitrogen fixation, quorum sensing, and metabolic control (Lenz et al. 2005; Nakamura et al. 2007; Romby et al. 2006; Skippington and Ragan 2012; Yuan et al. 2015; Zhan et al. 2016).

In the processes of bacterial growth and development, Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion radical (O2–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), are generated continuously (Blokhina et al. 2003; Imlay 2008). Consequently, living organisms, with enzymes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD), proteins such as thioredoxin and glutaredoxin, and molecules such as glutathione (Trotter and Grant 2003), have evolved defense mechanisms and genetic responses that limit oxidative stress by detoxifying ROS, including H2O2.

Because of its clear genetic background, Escherichia coli has been used as a model strain for scientific research and is a widely used strain in industrial production (Liang et al. 2011; Negrete and Shiloach 2017). However, facultative aerobic growth of organisms to help them acquire the ability to protect themselves against oxidative stress has been a challenge for the biotechnological industry, especially for the production of recombinant proteins.

OxyR, SoxRS and RpoS are three major regulators known to function as homeostasis-maintaining component in the context of cellular oxidative stress by acting as transcriptional regulators of several genes (Chiang and Schellhorn 2012). In addition, some molecules are constitutively present to scavenge chemically reactive oxygen or help maintain a reducing intracellular environment. For example, Fe2+ play a significant role in activation of molecular oxygen, reduction of ribonucleotides, decomposition of peroxides and electron transport, thereby protecting the cell or organism from oxidative stress (McHugh et al. 2003).

Recently, using synthetic sRNAs that was based on the abilities and characteristics of natural sRNAs led to the identification of a level of RNA-mediated regulation, greatly contributing to our understanding of the multiple levels of control used by cells and the interactions among these control mechanisms (Na et al. 2013; Yoo et al. 2013). In addition to the antioxidant ncRNA OxyS of E. coli (González-Flecha and Demple 1999), some ncRNAs act as positive regulators in Pseudomonas spp. to provide resistance to oxidative stress. In Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas syringae, the ncRNA RgsA has been reported to be important for resistance to oxidative stress (Gonzalez et al. 2008; Park et al. 2013). In the nitrogen-fixing strain Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501, the function of an ncRNA NfiS is related to the stress response; in the presence of 20 mM H2O2 or 0.3 M sorbitol, the nfiS mutant was more sensitive than the wild-type (WT) P. stutzeri A1501, whereas overexpression of NfiS led to enhanced resistance. Thus, NfiS plays an important role in the response to oxidative or osmotic stress, and NfiS likely contains another as-yet-unidentified nucleotide sequence that pairs with stress resistance-related target genes (Zhan et al. 2016).

To investigate whether NfiS has a similar function in E. coli, nfiS (NfiS-encoding gene) from Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501 was cloned into the mobilizable vector pLAFR3 and transformed into the E. coli strain Trans10 to obtain recombinant strain Trans10-nfiS, and Trans10-pLAFR3 (Trans10 harboring the plasmid pLAFR3) was constructed as a control. The WT E. coli and the recombinant strains were treated with 20 mM H2O2 for 10 min or shocked with 1.5 M NaCl for 60 min. The recombinant strains exhibited stronger resistance to H2O2 and osmotic stress than the WT E. coli. These results indicate that NfiS also plays a similar role in E. coli. Here, we report that an ncRNA from P. stutzeri A1501, namely, NfiS, improved the oxidative and osmotic stress resistance of E. coli. Further microarray analysis showed that NfiS influenced gene expression in E. coli, allowing investigation of the specific molecular mechanism underlying the improvement of oxidative and osmotic stress resistance in E. coli by NfiS.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. P. stutzeri A1501 was grown in minimal lactate medium or in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 30 °C as previously described (Desnoues et al. 2003). E. coli and derivatives were grown in LB medium at 37 °C. When appropriate, media were supplemented with 10 µg/mL antibiotic tetracycline (Tc).

Cloning of the nfiS gene from P. stutzeri A1501

The complete genome of P. stutzeri A1501 was deposited in the GenBank database with accession no. CP000304 (Yan et al. 2008). The complete nfiS gene amplified from A1501 genomic DNA was ligated into the plasmid pLAFR3, and then the resulting plasmid pLA-nfiS was transformed into E. coli Trans10 cells to generate the strain Trans10-nfiS. We next assayed if the identical size of NfiS (254 bp) was conferred to E. coli and expressed by reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Total RNA from Trans 10 and Trans 10-nfiS was extracted and converted into cDNA via reverse transcription (PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit, Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Synthesized cDNA samples were amplified by using primers nfiS-F (5′-CCGCTGTCTGGCCTGTT-3′) and nfiS-R (5′-CCATGGGTGCCCGAATC-3′).

Growth rate and culture conditions

For the growth assay, cells from an overnight culture in LB medium were centrifuged and resuspended in 65-mL flasks containing 10 mL of LB medium at an OD600 of 0.1, and then 400 μL bacterial suspensions were incubated in the automatic growth curve analyzer Bioscreen C FP-1100-C (OY Growth Curves AB Ltd, Finland) at 37 °C. Culture samples were taken every 20 min, and the cell density was determined spectrophotometrically at 600 nm (OD600).

H2O2 and NaCl shock treatments

For H2O2 shock treatments, E. coli strains were cultured overnight and transferred into fresh LB broth the next day until the OD600 increased to 0.6. Then, 20 mM H2O2 was added to the medium, and the culture was incubated at 30 °C and 220 rpm for 10 min. Next, 10 serial dilutions were prepared for all the strains, and 8 µL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 16 h.

For NaCl shock treatments, E. coli strains were cultured overnight and were transferred into fresh LB broth the next day until the OD600 increased to 0.6. Then, 1 mL of the suspension was collected, and the cells were resuspended with 1 mL of 1.5 M NaCl and incubated at 30 °C and 220 rpm for 1 h. Then, 10 serial dilutions were prepared for all strains, and 8 µL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 16 h.

Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis

Both WT E. coli Trans10 and Trans10-nfiS samples after H2O2 shock for 10 min were collected (see H2O2 shock treatment in “Materials and methods”). Total RNA samples were extracted from three independent experiments of the Trans10 and Trans10-nfiS strains. Isolation of RNA from E. coli was carried out by using a combination of TRIzol reagent and the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit with DNase I treatment (Invitrogen, USA). The concentration and purity of the RNA were evaluated using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) followed by 1.2% formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. cDNA was synthesized from 10 µg of total RNA using One-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagents (Affymetrix, USA) to produce biotin-labeled cDNA. The quality and quantity of the original RNA samples and the cDNA probes generated for array hybridization were determined with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Following fragmentation, 10 µg of cRNA was hybridized for 16 h at 45 °C on GeneChip Escherichia coli Genome Arrays. GeneChips were washed and stained in an Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 and scanned using the Scanner 3000 7G 4C system. The data were analyzed with Microarray Suite version 5.0 (MAS 5.0) using Affymetrix default analysis settings and global scaling as a normalization method. The trimmed mean target intensity of each array was arbitrarily set to 100. Log2 ratio > 1.0 or < − 1.0 was considered to be significantly different. Information for each probe was obtained according to Gene Ontology (GO) classification, and the genes were annotated for classification of functional and biological processes.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the innuPREP RNA Mini Kit (Analytik jena, Germany). For each sample, 1.5 μg of the total RNA of three independent biological replicates was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Japan) following the procedure in the manual. HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, China) was used to remove genomic DNA and generate first-strand cDNA. The produced cDNA was used to perform qRT-PCR using ChamQ™ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix. The reactions were performed using the 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA), and the relative expression of the genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. In this experiment, 16S rRNA was used as an internal standard, and data analysis was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Primer information is shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Prediction of the NfiS RNA target genes in E. coli

The target genes of ncRNA NfiS (254 bp) were predicted by using IntaRNA (Busch et al. 2008). The hybridization between the sRNA transcript sequence and the sequence comprising 300 nt upstream and 300 nt downstream of the start codon of each annotated gene was screened in the genome of Escherichia coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655. GO annotations with the default parameters and GO enrichment with EASE scores of 0.05 were determined with the functional annotation tool DAVID. Based on hybridization energy and accessibility of the interaction sites, only putative targets with predicted energy values less than or equal to − 15 kcal/mol were considered (Zhang et al. 2017); significance was defined at P < 0.05.

Microarray data accession number

The gene expression data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE124807.

Results

Growth properties of E. coli Trans10-nfiS

We validated the introduction and expression of NfiS using RT-PCR to confirm the results of the triparental conjugation experiments. mRNA from Trans10-nfiS yielded a PCR product of 143 bp, which is consistent with the expected RT-PCR product size amplified with specific primer sets nfiS-F and nfiS-R. In contrast, no significant specific bands were observed when mRNA from Trans10 was used as a template during PCR amplification (Fig. 1). These data showed that P. stutzeri species-specific nfiS can be transcribed to yield noncoding RNA NfiS.

To explore the effect of NfiS expression on the growth of E. coli Trans10, the growth performance of Trans10-nfiS was compared to that of Trans10. To eliminate interference from the mobilizable vector pLAFR3, a recombinant strain, Trans10-pLAFR3, harboring the empty pLAFR3 vector, was constructed and used as a negative control. As the semilogarithmic curves show, In LB medium, Trans10-nfiS exhibited a similar growth pattern to that of Trans10 (Fig. 2). It was concluded that introduction of the nfiS gene did not have any effect on the observable growth defect of E. coli Trans10 in LB medium.

NfiS-expressing E. coli exhibits distinct oxidative and osmotic stress tolerance

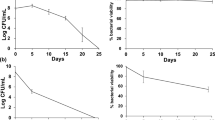

Bacterial ncRNAs are involved in diverse stress responses. Among these ncRNAs, the P. stutzeri strain-derived RNA NfiS has been reported to be involved in the control of nitrogen fixation and the response to oxidative and osmotic stress. In the presence of 20 mM H2O2 or 1.5 M NaCl, heterologous expression of NfiS in E. coli led to enhanced resistance, whereas the Trans10 strain exhibited high sensitivity (Fig. 3).

To determine whether NfiS improved the ability of Trans10 to resist multiple adverse environments as a global regulator, the cell survival rate was estimated by testing serial dilutions from 10−1 to 10−5 under heat shock (53 °C), alkaline conditions (pH 10), acidic conditions (pH 2.0) and 0.3 M sorbitol treatment. The ability to resist different stress factors is reflected by the number of colonies on the plates. In these experiments, we did not observe any increase in the number of colonies of Trans10-nfiS relative to Trans10, indicating that NfiS was not involved in the tested stress regulation pathways. Based on these studies, NfiS likely controls the response to certain types of stress, especially oxidative stress response-related genes, via unknown mechanisms.

Analysis of the E. coli Trans10-nfiS transcriptome under H2O2 shock conditions

The cell survival rate of Trans10-nfiS cells under H2O2 shock treatment was more distinguishable from that under osmotic stress, implying that NfiS may have a more essential role in regulating oxidative stress-related pathways. To clarify the potential mechanism of NfiS ncRNA in oxidative resistance, we performed DNA microarray analysis with both the recombinant Trans10-nfiS and WT E. coli Trans10 under identical H2O2 shock treatment conditions (see “Materials and methods” for details). The expression levels of several genes (two downregulated genes, fnr, katE and six upregulated genes, soxS, oxyR, arcA, arcB, katG and putA) observed in the microarray analyses were validated by using quantitative real-time PCR. Overall, these results were consistent with those obtained by transcriptome sequencing (Fig. 4).

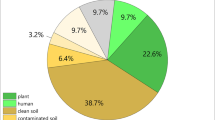

Our data showed that a total of 1184 genes were significantly altered (expression was changed by at least twofold) in Trans10-nfiS relative to Trans10, including 601 upregulated genes and 583 downregulated genes. These altered genes were further classified according to the COG functional classification system and were mainly divided into five functional categories (Fig. 5): stress response, regulation, metabolism related, transport or membrane protein and unknown function. Here, the oxidative stress response pathway is discussed in detail.

ROS overdose can cause a multitude of interrelated biochemical reactions in cells, including lipid peroxidation, covalent modification and oxidation of proteins and DNA lesions such as base damage, ultimately resulting in cell death (Blokhina et al. 2003). For E. coli, RpoS, OxyR, SoxSR and Fur were identified as the most crucial regulons for sensing ROS levels within the cell and subsequently controlling the expression of many specific genes or regulating target protein activities to protect organisms from the cytotoxic effects of oxidants. The differentially expressed RpoS OxyR, SoxSR and Fur regulons in two E. coli strains (Trans10 and Trans10-nfiS), both under H2O2 treatment, are listed in Additional file 1: Tables S2–S5, respectively.

For the 76 differentially expressed genes found in the RpoS regulon, the DNA repair exonuclease III gene xthA, which participates in oxidative-stress-induced DNA damage repair, was upregulated 7.75-fold in Trans10-nfiS relative to Trans10. The DNA mismatch repair protein gene mutS was upregulated by 3.38-fold. This may indicate that NfiS enhanced the DNA damage repair system to protect the cell from oxidative damage. The 39 genes regulated by OxyR can be divided into two categories: (1) genes involved in the direct elimination of H2O2 (katG, ahpC, ahpF, yhjA and hemF) and (2) genes involved in the regulation of redox potential (grx, gor, trxB, trxC, fhuF and dsbG). Microarray data showed that the expression of katG (hydroperoxidase I), ahpC, ahpF (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase component), yhjA (cytochrome c peroxidase) and hemF (coproporphyrinogen III oxidase) remained almost unchanged, while the glutathione reductase gene gor and thioredoxin reductase gene trxB were upregulated 2.97-fold and 7.28-fold, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S3). Thus, it is possible that NfiS, rather than direct clearance of H2O2, improved E. coli oxidation resistance via accumulation of glutathione reductase/thioredoxin reductase (Sengupta and Holmgren 2014), which is responsible for the oxidative-state activation of OxyR. A previous study revealed that numerous genes involved in oxidative stress resistance were SoxRS-dependent, including sodA (MnSOD), nfo (DNA repair endonuclease IV), zwf (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, G6PD), acnA (aconitate hydratase), fumC (fumarase), acrAB (efflux pump), fpr (flavodoxin/ferredoxin-NADP(+) reductase), fur (Fe uptake and regulator), fldAB (flavodoxin), and micF (Chiang and Schellhorn 2012). Among these genes, gcd (glucose dehydrogenase) was upregulated 3.19-fold, acrA was upregulated 3.12-fold and acrB was upregulated slightly as well as in Trans10-nfiS (Additional file 1: Table S4). No significant changes in fpr, fur, nfo, zwf, sodA and fldAB gene expression were detected, indicating that the enhancement of stress resistance was unrelated to these genes. fur has been reported to be activated by OxyR and SoxR, which are known regulators of oxidative stress (Zheng et al. 1999). Given that iron-sulfur cluster synthesis is susceptible to superoxide anions induced by H2O2 stress, the expression of the Fur regulon genes iscAUSRX (Fe–S cluster), fdx (reduced ferredoxin), hscAB (cochaperone for Fe–S cluster biosynthesis), pepB (aminopeptidase B), sseB (enhanced serine sensitivity protein) and sufESDCBA (Fe–S cluster assembly protein) were downregulated by different degrees. Of these genes, fdx and iscX were downregulated 2.22-fold and 2.26-fold, respectively. The decrease was further enhanced for the suf operon, and the genes sufE, sufS, sufD and sufC were downregulated 11.73-fold, 7.24-fold, 3.01-fold and 2.46-fold, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S5). Based on these studies, NfiS controls Fe–S cluster synthesis at the transcriptional level via regulation of both the OxyR/SoxRS regulatory cascade and certain stress response-related genes.

The expression of the cysteine synthesis-associated gene cluster (cys) and associated genes generally decreased (Additional file 1: Table S6), since cysteine residues and Fe–S clusters are sensitive to the ROS generated under H2O2 treatment. Superoxide anions disrupt iron-sulfur clusters, leading to the release of Fe2+, which reacts with H2O2 to form hydroxyl free radicals. The hydroxyl free radical is a type of strong oxidant that directly damages cysteine residues. H2O2 can also directly oxidize the cysteine residues of proteins. Superoxide anions and the denitrification intermediate nitric oxide anions form oxygen nitrite, which diffuses into cells and damages cysteine residues, so cysteine is often damaged as a direct target of ROS produced under oxidative stress.

Ribonucleotide reductases are widely present in prokaryotes. The biosynthesis of NTPs, the basic units for DNA replication, is catalyzed by the ribonucleotide reductase encoded by the nrd gene cluster (Torrents 2014). Via specific binding to four types of dNTPs, the active site of ribonucleotide reductase provides the substrate that is indispensable for the E. coli DNA damage repair system. Compared with Trans10 under oxidative stress conditions, Trans10-nfiS nrdHIEF mRNA expression increased 10.26-fold, 6.14-fold, 1.78-fold and 9.03-fold, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S7), indicating that the DNA damage repair ability of the strain was enhanced by the introduction of NfiS.

Biotin, also known as vitamin B7, is a necessary vitamin for growth. The synthesis of biotin in E. coli starts from heptanoic acid and is mainly completed by enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway (Eisenberg and Star 1968). The process is catalyzed by heptanoyl coenzyme A synthase, the 7-ketol-8 amino-pelargonic acid synthase BioF, the 7,8-diaminonucanoic acid synthase BioA, the desulfurization synthase BioD and the biotin synthase BioB. Under oxidative stress, biotin synthesis pathway genes in the NfiS expression strain were inhibited. For example, the expression levels of bioF, bioD and bioB were downregulated 3-fold, 3.17-fold and 1.8-fold, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S8).

Similarly, most of the acid resistance genes were downregulated more than twofold (Additional file 1: Table S9). There are four types of metabolites involved in the acid resistance pathways: glucose, arginine, glutamic acid and lysine (Richard and Foster 2004; Yoo et al. 2013). For the latter three acid resistance systems, in the presence of each of the amino acids, the decarboxylase can deacidify the amino acid and continuously consume intracellular protons, preventing extracellular protons from flowing into the cell and reducing the intracellular pH value to alleviate the damage caused by the low extracellular pH. However, compared with Trans10, the expression of glutamic acid-dependent genes was significantly inhibited in Trans10-nfiS. The glutamic acid decarboxylases gadA and gadB were downregulated 11.5-fold and 11.6-fold, respectively. The glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid reverse transporter gene gadC was downregulated 6.96-fold. We speculate that Trans10-nfiS is induced to express antioxidant genes by consuming ATP and NADPH, which leads to depletion of the substrates required for resistance to acid stress and for energy, eventually suppressing the expression of acid resistance genes.

Hfq is an important molecular chaperone reported to be involved in sRNA activity and function (Vytvytska et al. 2000). In this study, we did not find a significant change of Hfq in Trans10 due to the introduction of nfiS.

In silico prediction of genes as targets of NfiS in E. coli

To investigate potential regulation by NfiS, we next performed an in silico analysis using the IntaRNA program. The output table summarizes the best 100 predicted interactions (Additional file 1: Table S10), but only the top 25 target genes (P-value lower than 0.5) were selected for further discussion (Table 2). A region within the leader of oweS (b2358, also known as yfdO) mRNA and a region within the coding sequence (CDS) of xanP (b3654, also known as yicE) mRNA were confirmed as the high-scoring interaction sites for NfiS. Interestingly, the predicted gene oweS (encoding prophage CPS-53 protein YfdO) has been reported to enhance resistance to oxidative stress (Wang et al. 2010). Moreover, prophages containing YfdO provide multiple benefits (withstanding osmotic, oxidative and acid stresses, increasing growth, and influencing biofilm formation) to the host for survival under adverse environmental conditions. The YicE protein is a member of the NCS2 family of nucleobase transporters. YicE was shown to be present in the plasma membrane of E. coli and function as specific, high-affinity transporter for xanthine in a proton motive force-dependent manner, which is an essential process that generates functional substrates needed for the repair of double-strand breaks in E. coli. Thus, our computational analysis suggests that NfiS may directly regulate oweS and xanP mRNA expression in E. coli Trans10.

The impact of NfiS on oweS and xanP gene expression was less profound compared to the impact on ypjD (encoding cytochrome c assembly family protein), rho (encoding transcription termination factor Rho), mzrA (encoding modulator of EnvZ/OmpR regulon), elyC (encoding envelope biogenesis factor), yohC (putative inner membrane protein), cynR (encoding DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator CynR), yagF (encoding D-xylonate dehydratase) and aqpZ (water channel AqpZ) estimated by transcriptome profiling, although there had been no previous report that these differentially expressed genes are involved in the antioxidant regulatory pathway. At present, whether they can bind to NfiS under oxidative stress conditions remains uncertain.

Discussion

It has been suggested that the regulation of ncRNA diversity provides an opportunity for the generation of novel functional strains by genetic engineering or synthetic biological methods. It has been reported that, NfiS, coordinates oxidative stress response and nitrogen fixation via base pairing with katB mRNA and nifK mRNA (Zhang et al. 2019). This work examines NfiS, an ncRNA specific to P. stutzeri, which plays a similar role in E. coli as an antioxidant. Heterologous expression of NfiS in Trans10 cells enhanced the oxidative stress resistance process, which is consistent with the role of NfiS in P. stutzeri. In addition, examination of differential gene expression in recombinant E. coli identified an array of genes associated with ROS clearance. It is proposed that the primary function of NfiS in P. stutzeri is associated with the stress response and that NfiS likely contains another nucleotide sequence that pairs with other, as-yet-unidentified target genes.

To the best of our knowledge, E. coli has several major regulators that are up-regulated during oxidative stress, including OxyR, SoxRS, RpoS and Fur. OxyR negatively regulates the expression of its encoding gene (oxyR) and positively regulates an adjacent small RNA gene (oxyS). OxyR controls a regulon of almost 40 genes, which protect the cell from the toxic effects of H2O2. The soxR and soxS are adjacent and divergently transcribed in E. coli (Wu and Weiss 1991). Proteins encoded by soxR and soxS constitute a two-stage regulatory system in which SoxR, when activated, induces the expression of soxS, which in turn regulates several genes that are important for the oxidative stress response. OxyR and SoxR are activated by conformational changes due to oxidization, whereas RpoS leads to increased recruitment of RNA polymerase to RpoS-dependent promoters. To some extent, Iron homeostasis and the oxidative stress response are linked. OxyR and SoxRS are capable of induce Fur expression, via the binding of OxyR to the fur promoter and the binding of SoxS to the upstream fldA (encoding flavodoxin) promoter (Varghese et al. 2007). Fur activity can be diminished in the H2O2− containing environments and OxyR-mediated induction of Fur was found to help alleviate the loss of Fur activity (Pohl et al. 2003). However, in P. stutzeri A1501, genes involved in ROS resistance and protection from oxidative stress remain to be studied.

Instead of obtaining all genes involved in oxidative stress, the purpose of the transcriptome assay design was to excavate possible targets of the ncRNA. By using genome-wide microarray analysis, changes in the expression levels of genes involved in oxidative resistance were detected under 20 mM H2O2 treatment. According to the four major regulators activated during oxidative stress, these genes can be divided into OxyR-, SoxRS-, RpoS- and Fur-dependent genes. Among these genes, the gor, trx, agn43 and uxuA genes regulated by OxyR (Wallecha et al. 2014) were upregulated more than twofold. Additionally, SoxR-dependent genes, such as yggX, gcd and acrAB, and the RpoS-dependent genes xthA and mutS were upregulated. Homeostatic control of free intracellular iron levels is important for minimization of oxidative stress. Fur binds to DNA at a Fur box to repress iron acquisition genes, which is consistent with a role for Fur in oxidative stress resistance. The expression levels of the isc operon and suf operon (Fe–S cluster formation) were decreased significantly. It is hypothesized that NfiS controls these target genes to participate in the oxidative resistance of E. coli. In addition, NfiS affects the synthesis of cysteine and biotin in the cell, promotes the activity of ribonucleotide reductase, inhibits the synthesis of iron-sulfur clusters and affects the expression of the glutamate-dependent acid tolerance system, and these biological pathways or processes can also play important roles in enhancing the antioxidant tolerance of E. coli.

We noticed that rpoS, oxyR, soxSR and fur were not among the differentially expressed genes, which does not rule out important roles for those genes in oxidative resistance since the transcriptome analyses were designed to explore pathways influenced by NfiS. It is possible that many vital regulators involved in oxidative stress tolerance were expressed highly within both Trans10 and Trans10-nfiS, but this was not reflected by the transcriptome results. In summary, the nfiS gene cloned from P. stutzeri A1501 has been shown to protect E. coli from ROS. Many antioxidant genes in E. coli could be identified using differential transcriptomic analysis, and a potential mechanism of action for NfiS was identified. Bacterial small RNAs (sRNAs) have been implicated in various aspects of post-transcriptional gene regulation without modification of chromosomal sequences. Various strategies for systems metabolic engineering can be used for further strain improvement followed the superior platform strain and effective sRNA target genes have been identified. The work presented here enables the rapid development of high-performance microbial strains.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- ncRNA:

-

noncoding RNA

- A1501:

-

Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501

- WT:

-

wild type

- Tc:

-

tetracycline

- OD:

-

optical density

- RT-PCR:

-

reverse transcription PCR

- qRT-PCR:

-

quantitative real-time PCR

- bp:

-

base pair

- SD:

-

standard deviation

References

Blokhina O, Virolainen E, Fagerstedt KV (2003) Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann Bot 91:179–194

Busch A, Richter AS, Backofen R (2008) IntaRNA: efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets incorporating target site accessibility and seed regions. Bioinformatics 24:2849–2856

Chiang SM, Schellhorn HE (2012) Regulators of oxidative stress response genes in Escherichia coli and their functional conservation in bacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys 525:161–169

Desnoues N, Lin M, Guo X, Ma L, Carreno-Lopez R, Elmerich C (2003) Nitrogen fixation genetics and regulation in a Pseudomonas stutzeri strain associated with rice. Microbiology 149:2251–2262

Eisenberg MA, Star C (1968) Synthesis of 7-oxo-8-aminopelargonic acid, a biotin vitamer, in cell-free extracts of Escherichia coli biotin auxotrophs. J Bacteriol 96:1291–1297

Gonzalez N, Heeb S, Valverde C, Kay E, Reimmann C, Junier T, Haas D (2008) Genome-wide search reveals a novel GacA-regulated small RNA in Pseudomonas species. BMC Genomics 9:167

González-Flecha B, Demple B (1999) Role for the oxyS gene in regulation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:3833–3836

Imlay JA (2008) Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem 77:755–776

Lenz DH, Miller MB, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV, Bassler BL (2005) CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 58:1186–1202

Liang JC, Bloom RJ, Smolke CD (2011) Engineering biological systems with synthetic RNA molecules. Mol Cell 43:915–926

McHugh JP, Rodriguez-Quinones F, Abdul-Tehrani H, Svistunenko DA, Poole RK, Cooper CE, Andrews SC (2003) Global iron-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli. A new mechanism for iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem 278:29478–29486

Na D, Yoo SM, Chung H, Park H, Park JH, Lee SY (2013) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using synthetic small regulatory RNAs. Nat Biotechnol 31:170–174

Nakamura T, Naito K, Yokota N, Sugita C, Sugita M (2007) A cyanobacterial non-coding RNA, Yfr1, is required for growth under multiple stress conditions. Plant Cell Physiol 48:1309–1318

Negrete A, Shiloach J (2017) Improving E. coli growth performance by manipulating small RNA expression. Microb Cell Fact 16:198

Park SH, Butcher BG, Anderson Z, Pellegrini N, Bao Z, D’Amico K, Filiatrault MJ (2013) Analysis of the small RNA P16/RgsA in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000. Microbiology 159:296–306

Pohl E, Haller JC, Mijovilovich A, Meyer-Klaucke W, Garman E, Vasil ML (2003) Architecture of a protein central to iron homeostasis: crystal structure and spectroscopic analysis of the ferric uptake regulator. Mol Microbiol 47:903–915

Richard H, Foster JW (2004) Escherichia coli glutamate- and arginine-dependent acid resistance systems increase internal pH and reverse transmembrane potential. J Bacteriol 186:6032–6041

Romby P, Vandenesch F, Wagner EG (2006) The role of RNAs in the regulation of virulence-gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:229–236

Sengupta R, Holmgren A (2014) Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin-mediated redox regulation of ribonucleotide reductase World. J Biol Chem 5:68–74

Skippington E, Ragan MA (2012) Evolutionary dynamics of small RNAs in 27 Escherichia coli and Shigella genomes. Genome Biol Evol 4:330–345

Staskawicz B, Dahlbeck D, Keen N, Napoli C (1987) Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J Bacteriol 169:5789–5794

Torrents E (2014) Ribonucleotide reductases: essential enzymes for bacterial life. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:52

Trotter EW, Grant CM (2003) Non-reciprocal regulation of the redox state of the glutathione–glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems. EMBO Rep 4:184–188

Varghese S, Wu A, Park S, Imlay KR, Imlay JA (2007) Submicromolar hydrogen peroxide disrupts the ability of Fur protein to control free-iron levels in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 64:822–830

Vytvytska O, Moll I, Kaberdin VR, von Gabain A, Bläsi U (2000) Hfq (HF1) stimulates ompA mRNA decay by interfering with ribosome binding. Genes Dev 14:1109–1118

Wallecha A, Oreh H, van der Woude MW, deHaseth PL (2014) Control of gene expression at a bacterial leader RNA, the agn43 gene encoding outer membrane protein Ag43 of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 196:2728–2735

Wang X, Kim Y, Ma Q, Hong SH, Pokusaeva K, Sturino JM, Wood TK (2010) Cryptic prophages help bacteria cope with adverse environments. Nat Commun 1:1–9

Wassarman KM, Zhang AX, Storz G (1999) Small RNAs in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol 7:37–45

Wu J, Weiss B (1991) Two divergently transcribed genes, soxR and soxS, control a superoxide response regulon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 173:2864–2871

Yan Y, Yang J, Dou Y, Chen M, Ping S, Peng J, Lu W, Zhang W, Yao Z, Li H, Liu W, He S, Geng L, Zhang X, Yang F, Yu H, Zhan Y, Li D, Lin Z, Wang Y, Elimerich C, Lin M, Jin Q (2008) Nitrogen fixation island and rhizosphere competence traits in the genome of root-associated Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:7564–7569

Yoo SM, Na D, Lee SY (2013) Design and use of synthetic regulatory small RNAs to control gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nat Protoc 8:1694–1707

Yuan X, Khokhani D, Wu X, Yang F, Biener G, Koestler BJ, Raicu V, He C, Waters CM, Sundin GW, Tian F, Yang CH (2015) Cross-talk between a regulatory small RNA, cyclic-di-GMP signalling and flagellar regulator FlhDC for virulence and bacterial behaviours. Environ Microbiol 17:4745–4763

Zhan Y, Yan Y, Deng Z, Chen M, Lu W, Lu C, Shang L, Yang Z, Zhang W, Wang W, Li Y, Ke Q, Lu J, Xu Y, Zhang L, Xie Z, Cheng Q, Elmerich C, Lin M (2016) The novel regulatory ncRNA, NfiS, optimizes nitrogen fixation via base pairing with the nitrogenase gene nifK mRNA in Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E4348–E4356

Zhang Y, Yan D, Xia L, Zhao X, Osei-Adjei G, Xu S, Sheng X, Huang X (2017) The malS-5′UTR regulates hisG, a key gene in the histidine biosynthetic pathway in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Can J Microbiol 63:287–295

Zhang H, Zhan Y, Yan Y, Liu Y, Hu G, Wang S, Yang H, Qiu X, Liu Y, Li J, Lu W, Elmerich C, Lin M (2019) The Pseudomonas stutzeri-specific regulatory ncRNA, NfiS, targets the katB mRNA encoding a catalase essential for optimal oxidative resistance and nitrogenase activity. J Bacteriol 19:e00334-00319

Zheng M, Doan B, Schneider TD, Storz G (1999) OxyR and SoxRS regulation of fur. J Bacteriol 181:4639–4643

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770067, 31470205 and 31470174), the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB755700), and the Ministry of Agriculture (Transgenic Program, No. 2016ZX08009003-002). This study was also conducted with the support of the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (2014-2018), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Non-profit Scientific Institution (0392017002) and the Postgraduate Domestic Visiting Research Project of Jiangxi Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY and ML designed the work; TH and GH performed the research study; TH and GH analysis the data; GH, YH and YY drafted the manuscript; WL and YZ were involved in critically revision the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Additional tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, G., Hu, T., Zhan, Y. et al. NfiS, a species-specific regulatory noncoding RNA of Pseudomonas stutzeri, enhances oxidative stress tolerance in Escherichia coli. AMB Expr 9, 156 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0881-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0881-7