Abstract

The demand for ammonia is expected to increase in the future because of its importance in agriculture, industry, and hydrogen transportation. Although the Haber–Bosch process is known as an effective way to produce ammonia, the process is energy-intensive. Thus, an environmentally friendly ammonia production process is desired. In this study, we aimed to produce ammonia from amino acids and amino acid-based biomass-like resources by modifying the metabolism of Escherichia coli. By engineering metabolic flux to promote ammonia production using the overexpression of the ketoisovalerate decarboxylase gene (kivd), derived from Lactococcus lactis, ammonia production from amino acids was 351 mg/L (36.6% yield). Furthermore, we deleted the glnA gene, responsible for ammonia assimilation. Using yeast extract as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, the resultant strain produced 458 mg/L of ammonia (47.8% yield) from an amino acid-based biomass-like material. The ammonia production yields obtained are the highest reported to date. This study suggests that it will be possible to produce ammonia from waste biomass in an environmentally friendly process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia is one of the most valuable materials in all aspects of our daily life. Mostly, it is used as a fertilizer in agriculture, and another important usage is as a precursor for nitrogen-containing chemicals such as nitriles, amines, hydrazine, and urea. Additionally, it is anticipated that ammonia has potentiality as a hydrogen liquid carrier in the proposed hydrogen economy (Lan et al. 2012; Miura and Tezuka 2014).

Ammonia synthesis was industrially started by Haber at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Haber–Bosch process now sustains our life by supplying nitrogen fertilizers, keeping up with the increasing demands for food (Erisman et al. 2008). Global production of ammonia reached 146 million tons in 2015 (Gocha 2015). However, we have to consider energy consumption of ammonia production by the Haber–Bosch process because the process needs a lot of energy. The process requires high temperatures (400–600 °C) and high pressures (20–40 MPa), and it is said that more than 1% of the energy generated in the world is used for the Haber–Bosch process (Schrock 2006). Therefore, a more environmentally friendly ammonia production process is desired.

Ammonia production using microorganisms from waste biomass, which is abundant and nitrogen-rich, can be performed at ordinary temperatures and normal pressures. Cleavage of the nitrogen–nitrogen triple bond consumes maximum energy in the Haber–Bosch process. In contrast, nitrogen is already fixed in waste biomass, so ammonia can be easily produced by bacterial dissimilation.

In this study, we show a general concept of ammonia production from waste biomass with metabolically engineered microorganisms. To efficiently produce ammonia, Escherichia coli (E. coli) was chosen as the host strain because of the accumulated knowledge of its metabolism (Deng et al. 2005; Yim et al. 2011). We planned to direct the amino acid degradation pathway to produce ammonia. First, overexpression of a decarboxylase gene was used as a driving force for ammonia production. Second, we prepared E. coli strains that lacked the genes involved in ammonia assimilation, and investigated their influence on ammonia production. By combining these two strategies, we constructed an E. coli strain suitable for ammonia production.

Materials and methods

Media

Luria–Bertani (LB) medium was prepared with 10 g/L Bacto™ Tryptone (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Detroit, MI, USA), 5 g/L Bacto™ Yeast Extract (Becton) and 10 g/L NaCl (Wako chemicals, Osaka, Japan). M9-YE medium was prepared with 6 g/L K2HPO4, 3 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 7.25 g/L yeast extract, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgSO4. In the experiment for the examination of effects of nitrogen sources on ammonia production, Bacto™ Tryptone (Becton), Bacto™ Peptone (Becton), or Bacto™ Casamino acids (Becton) were used instead of Bacto™ Yeast Extract in M9-YE medium. Ampicillin (Meiji Seika Pharma, Tokyo, Japan, 100 μg/mL) and kanamycin (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan, 25 μg/mL) were added as appropriate.

Construction of E. coli strains

All primers and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1, respectively. To clone the kivd gene, which encodes keto acid decarboxylase, genomic DNA of a Lactococcus lactis subsp. (ATCC 19435D-5, purchased from the ATCC), was used as a PCR template, with primers YN31/YN32. To clone cadA, gadA, or ilvH genes, firstly genomic DNA of E.coli DH5α (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was extracted using the Genomic-tip 100/G kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Next, the genomic DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification with primers YN33/YN34, YN35/YN36, or YN39/YN40, respectively. Resultant PCR products were cloned into the pTrcHis2-TOPO® vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) by TA-cloning (Fig. 1a). The control strain was E. coli DH10B; harboring the plasmid pTrcHis2-TOPO®/lacZ (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein production was validated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 5–20% e-PAGEL (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) and Full Range RPN800E protein markers (GE healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Proteins on the gel were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Plasmids for overexpression of decarboxylase and the method for gene deletion in Escherichia coli. a Upper side plasmids for kivd overexpression. Control vector (upper left) and pTrc-His2-kivd (upper right). cadA, gadA, or ilvH gene is used instead of kivd gene in the right plasmid for the overexpression of these genes. Lower side plasmids required for gene deletion in E. coli. pKD13 (lower left) is a template plasmid for the amplification of kanamycin resistance gene. pKD46 (lower right) is a plasmid that increases homologous recombination efficiency in E. coli chromosome. b A simple gene knockout strategy by homologous recombination. P1 or P2 priming site, H1 or H2 homologous recombination site

Gene deletion was performed using a homologous recombination system using lambda Red proteins according to the method by Datsenko (Fig. 1b) (Datsenko and Wanner 2000). The plasmid and method for gene deletion are shown in Fig. 1a and b, respectively.

Ammonia production

All cultivations were performed in a shaker (TAITEC, Saitama, Japan) at 165 rpm and 37 °C. For pre-culture, E. coli strains were cultivated in 5 mL LB medium at 37 °C overnight. The overnight culture was inoculated into 2.5 mL of M9-YE medium, or other media, to achieve an initial OD600 value of 0.5. Cells were grown for 2.5 h before adding 0.1 mM (final concentration) of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). After adding IPTG, cells were grown for 24 h. Ammonia meter (Ion meter TiN-9001, Toko Chemical Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure ammonia dissolved in the culture supernatant. Ammonia yields in M9-YE medium and other nitrogen-containing media were calculated based on the nitrogen contents in the BD Bionutrients™ Technical Manual Third edition (BD Biosciences 2015). Referring to the manual, for example, the theoretical maximum ammonia production in M9-YE medium (containing 7.25 g/L of yeast extract) was calculated to be 960 mg/L.

Results

Overexpression of 2-keto acid decarboxylase genes

To produce ammonia from amino acids, we planned to modify catabolism of amino acids in E. coli. The catabolic pathway of amino acids in E. coli is shown in Fig. 2. Natively, ammonia lyases such as ilvA (Eisenstein 1990), or transaminases such as ilvE (Inoue et al. 1988) catalyze the elimination of amino groups from amino acids. As a result of the elimination of amino groups, 2-keto acids are produced. Thus, we hypothesized that an irreversible decarboxylation of these 2-keto acids could be a driving force to engineer the metabolic flux toward ammonia production (Fig. 3, upper).

First, we examined the effect of selected decarboxylases on ammonia production; kivd (α-ketoisovalerate decarboxylase) (de la Plaza et al. 2004), gadA (glutamate decarboxylase) (Waterman and Small 2003), cadA (lysine decarboxylase) (Lemonnier and Lane 1998), and ilvH (acetolactate synthase) (Defelice et al. 1974). In these experiments, ammonia production was performed in M9-YE medium using yeast extract as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen. We used yeast extract as a model of waste biomass because it contains abundant amino acids as a nitrogen source (Biosciences 2015). As a result, we found that the kivd-overexpressing E. coli strain achieved the highest ammonia production (351 mg/L, 36.6% yield), while the control E. coli strain produced some ammonia using the native ammonia metabolism (Table 2).

Gene deletion of E. coli to improve ammonia production

To improve the efficacy of ammonia production, we deleted genes involved in ammonia assimilation. We chose two genes, glnA (glutamine synthetase) and gdhA (glutamate dehydrogenase), as knockout candidates to produce increased amounts of ammonia (Fig. 3, lower). Glutamate and glutamine are the major products of ammonia assimilation and they serve as intracellular nitrogen donors. Glutamine synthetase (GS) and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) assimilate most of the ammonia in E. coli, according to following reactions (van Heeswijk et al. 2013):

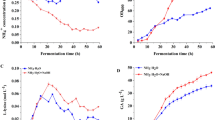

Deletion of glnA (ΔglnA) or gdhA blocks ammonia re-uptake and lead to secretion of ammonia into the media. Therefore, we individually deleted each of these genes in E. coli to try to improve ammonia yield. The amount of ammonia produced by these gene-deleted strains was evaluated in combination with the overexpression of kivd in M9-YE medium. As shown in Fig. 4, ammonia production reached 458 mg/L (47.8% yield) when the overexpression of kivd and deletion of glnA was combined. The reason why ammonia production did not improve in the gdhA deleted strain (Fig. 4) was thought to be a property of GDH. GDH has low affinity for ammonia (KM = 1–2 mM) (Sharkey and Engel 2008), while GS has high affinity (KM = 0.1 mM) (van Heeswijk et al. 2013). Hence, GDH is less efficient in low ammonia concentrations, such as in M9-YE medium.

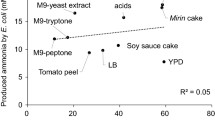

Next, we examined the effect of nitrogen source on ammonia production. Efficiency of ammonia production is affected by nitrogen content and difficulty of decomposition. Four media were used for ammonia production by the kivd + ΔglnA strain (Table 3). The yield in M9-YE medium was higher than that in the other media, except for the medium using casamino acids. The yields from peptone or tryptone media were low, probably because they contain long-chain peptides that E. coli cannot degrade (Huo et al. 2011). The ammonia yield from casamino acids was slightly higher than that from yeast extract (Table 3). The reason may be that the content of amino nitrogen per total nitrogen in casamino acids is higher than that in yeast extract (Table 4), leading to efficient ammonia production in casamino acid-based medium by E. coli.

Discussion

The demand for ammonia is expected to grow in the future. Recent studies examined ammonia production using microorganisms such as nitrogen-fixing bacteria (Higo et al. 2016). In this study, we focused on waste biomass, which has abundant nitrogen-containing compounds. By engineering ammonia metabolism in E. coli, the best strain produced 458 mg/L of ammonia from 7.25 g/L of yeast extract (Fig. 4). This ammonia yield is 23% higher than that in the previous study (Choi et al. 2014). Our study demonstrated that ammonia could be recovered in a low energy-consuming manner and that it would be possible to cover some of the increasing demand for ammonia in the future.

As shown in Table 4, yeast extract (Becton) was selected as the nitrogen source because more than 60% of nitrogen-containing compounds in yeast extract are easily degradable amino acids. The yield of ammonia is affected by the form of nitrogen in a medium. As shown in Table 3, the ammonia yield in M9-YE medium was higher than the media using peptone or tryptone, and equivalent to the medium using casamino acids. While yeast extract or casamino acids contain a lot of amino acids, peptone and tryptone consist of proteins and long-chain peptides (Table 4). Because E. coli cannot directly utilize proteins and long-chain peptides as a nutrient source, they must be decomposed into short-chain peptides before ammonia production (Huo et al. 2011). This is done by heterologous expression of strong proteases in E. coli (Choi et al. 2014; Su et al. 2012).

The ammonia yield with the best strain (kivd + ΔglnA) reached 47.8%. The remaining 52.2% was thought to be used for cell biomass or not catabolized. In order to increase the yield of ammonia, it is necessary to balance the growth of E. coli and ammonia production. The more E. coli grows, the less ammonia is produced in media, because overgrowth of E. coli leads to accumulation of ammonia in the form of cell biomass. Optimization of the balance between growth and ammonia production will be required to achieve the best yield. There have been studies trying to produce chemicals efficiently with the minimum growth required for production (Soma et al. 2014; Brockman and Prather 2015). For example, Soma et al. constructed two modes, a growth mode and a production mode, and engineered cells transitioned from growth mode to production mode automatically in culture. Strategies taken in these studies can be applied to increase ammonia yield.

Abbreviations

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- SDS-PAGE:

-

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- IPTG:

-

isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside

- GS:

-

glutamine synthetase

- GDH:

-

glutamate dehydrogenase

- B. subtilis :

-

Bacillus subtilis

References

BD biosciences (2015) BD bionutrients™ Technical Manual. Available via DIALOG. http://www.bd.com/ds/technicalCenter/misc/lcn01558-bionutrients-manual.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2017

Brockman IM, Prather KLJ (2015) Dynamic knockdown of E. coli central metabolism for redirecting fluxes of primary metabolites. Metab Eng 28:104–113

Choi KY, Wernick DG, Tat CA, Liao JC (2014) Consolidated conversion of protein waste into biofuels and ammonia using Bacillus subtilis. Metab Eng 23:53–61

Datsenko KA, Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:6640–6645

de la Plaza M, de Palencia PF, Pelaez C, Requena T (2004) Biochemical and molecular characterization of alpha-ketoisovalerate decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the formation of aldehydes from amino acids by Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 238:367–374

Defelice M, Guardiola J, Esposito B, Iaccarino M (1974) Structural genes for a newly recognized acetolactate synthase in Escherichia-coli K-12. J Bacteriol 120:1068–1077

Deng MD, Severson DK, Grund AD, Wassink SL, Burlingame RP, Berry A, Running JA, Kunesh CA, Song L, Jerrell TA, Rosson RA (2005) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for industrial production of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine. Metab Eng 7:201–214

Eisenstein E (1990) Cloning, expression, purification, and characterization of biosynthetic threonine deaminase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 266:5801–5807

Erisman JW, Sutton MA, Galloway J, Klimont Z, Winiwarter W (2008) How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat Geosci 1:636–639

Gocha A (2015) USGS mineral commodity summary 2015 highlights. Am Ceram Soc Bull 94:33–35

Higo A, Isu A, Fukaya Y, Hisabori T (2016) Efficient gene induction and endogenous gene repression systems for the filamentous Cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Plant Cell Physiol 57:387–396

Huo YX, Cho KM, Rivera JGL, Monte E, Shen CR, Yan YJ, Liao JC (2011) Conversion of proteins into biofuels by engineering nitrogen flux. Nat Biotechnol 29:346–351

Inoue K, Kuramitsu S, Aki K, Watanabe Y, Takagi T, Nishigai M, Ikai A, Kagamiyama H (1988) Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase of Escherichia coli: overproduction and properties. J Biol Chem 104:777–784

Lan R, Irvine JTS, Tao SW (2012) Ammonia and related chemicals as potential indirect hydrogen storage materials. Int J Hydrogen Energy 37:1482–1494

Lemonnier M, Lane D (1998) Expression of the second lysine decarboxylase gene of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Sgm 144:751–760

Miura D, Tezuka T (2014) A comparative study of ammonia energy systems as a future energy carrier, with particular reference to vehicle use in Japan. Energy 68:428–436

Schrock RR (2006) Reduction of dinitrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:17087

Sharkey MA, Engel PC (2008) Apparent negative co-operativity and substrate inhibition in overexpressed glutamate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 281:132–139

Soma Y, Tsuruno K, Wada M, Yokota A, Hanai T (2014) Metabolic flux redirection from a central metabolic pathway toward a synthetic pathway using a metabolic toggle switch. Metab Eng 23:175–184

Su LQ, Chen S, Yi L, Woodard RW, Chen J, Wu J (2012) Extracellular overexpression of recombinant Thermobifida fusca cutinase by alpha-hemolysin secretion system in E. coli BL21(DE3). Microb Cell Fact 11:8

van Heeswijk WC, Westerhoff HV, Boogerd FC (2013) Nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli: putting molecular data into a systems perspective. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:628–695

Waterman SR, Small PLC (2003) Transcriptional expression of Escherichia coli glutamate-dependent acid resistance genes gadA and gadBC in an hns rpoS mutant. J Bacteriol 185:4644–4647

Yim H, Haselbeck R, Niu W, Pujol-Baxley C, Burgard A, Boldt J, Khandurina J, Trawick JD, Osterhout RE, Stephen R, Estadilla J, Teisan S, Schreyer HB, Andrae S, Yang TH, Lee SY, Burk MJ, Van Dien S (2011) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat Chem Biol 7:445–452

Authors’ contributions

Planning and designing of study: YM, HY, YT, WA, MU; Experimentation and result analysis: YM, HY; Manuscript Drafting: YM, HY, YT, WA, MU. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Taizo Hanai (Kyushu University) for the kind gift of plasmids and advice for gene deletion.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All the data are presented in the main paper or Additional file 1.

Consent for publication

This article does not contain any individual person’s data.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies concerned with experimentation on human or animals.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikami, Y., Yoneda, H., Tatsukami, Y. et al. Ammonia production from amino acid-based biomass-like sources by engineered Escherichia coli . AMB Expr 7, 83 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-017-0385-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-017-0385-2