Abstract

Duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV), a member of the family Flaviviridae and an economically important pathogen with a broad host range, leads to markedly decreased egg production. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the host-DTMUV interaction remains unclear. Here, we performed high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to study the dynamic changes in host gene expression at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 h post-infection (hpi) in duck embryo fibroblasts (DEF) infected with DTMUV. A total of 3129 differentially expressed genes (DEG) were identified after DTMUV infection. Gene Ontology (GO) category and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis revealed that these DEG were associated with multiple biological functions, including signal transduction, host immunity, virus infection, cell apoptosis, cell proliferation, and pathogenicity-related and metabolic process signaling pathways. This study analyzed viral infection and host immunity induced by DTMUV infection from a novel perspective, and the results provide valuable information regarding the mechanisms underlying host-DTMUV interactions, which will prove useful for the future development of antiviral drugs or vaccines for poultry, thus benefiting the entire poultry industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV) is an arbovirus of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. DTMUV is an enveloped virus with a single-stranded, positive-polarity RNA genome that is approximately 11 kb in length [1]. Beginning in April 2010, an outbreak of DTMUV occurred in major duck farming regions in China [2]. Since then, DTMUV has also caused serious damage to the duck industry in Southeast Asian countries Thailand and Malaysia, as well as in China [3,4,5]. The slow growth of poultry, the sharp decline in egg production, and even the suspension of production have caused major economic losses [6]. Several studies have revealed that DTMUV has a wide host range, infecting ducks, chickens, geese, pigeons and house sparrows [7, 8]. Moreover, more than 70% of duck industry workers were reported to have Abs against DTMUV in the serum samples tested, and ~50% of oral swab samples were found to be positive for DTMUV RNA [9]. These studies clearly prove that DTMUV is likely to spread from ducks to other non-avian hosts and even humans. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the pathogenic mechanisms of DTMUV to allow the design of better disease control strategies.

China raises the largest number of ducks among all countries worldwide. Ducks are a natural host of DTMUV, as DTMUV and DTMUV antibodies have been found repeatedly in various domesticated ducks, and global serological evidence of DTMUV infection has been reported in a variety of wild waterfowl species [7, 10]. Duck embryo fibroblasts are the primary target cells of DTMUV and play a vital role in in vitro studies of host-DTMUV interactions [11, 12]. However, few studies have used DEF to investigate differential gene expression in response to DTMUV infection, which may provide important information about host-DTMUV interactions at the transcriptional level and in terms of biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Very recently, next-generation sequencing techniques such as RNA-Seq, which is a powerful approach for transcriptome profiling, have revealed dynamic changes in host gene expression during pathogen infections and have been employed to study various viral infections and diseases [13,14,15].

The aim of the current study was to use the RNA-Seq method to conduct a comparative transcriptome analysis of DEF in response to DTMUV infection at different time points (12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 hpi) and to analyze the dynamics of host gene expression during viral infection. The results may provide novel information that will increase our understanding of the pathogenesis of DTMUV and the mechanisms underlying virus-host interactions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and virus infection

Duck embryo fibroblasts were obtained from 10-day-old duck embryos according to the manufacturer’s instructions [16]. In this study, DEF were cultured in plates containing Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (NBS, Gibco) at 37 ℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. When DEF reached ~90% confluence, they were mock-infected or infected with DTMUV CQW1 strain (GenBank: KM233707.1) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 [17, 18]. After the virus was adsorbed in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 1 h, the inoculum was replaced with maintenance medium (DMEM containing 2% NBS), and the cell samples were collected at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 hpi, respectively. All duck embryos used in this study were selected in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Chinese Council on Animal Care.

RNA isolation, cDNA library construction and RNA-Seq

Cellular and viral RNA were extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and subsequently treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). RNA purity, concentration, and integrity were assessed using a Nano drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nano drop Technologies, CA, USA), a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, CA, USA), respectively. A cDNA library for each sample was constructed with an RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, 3 μg of RNA was used to enrich poly (A) mRNA, which was fragmented into short pieces by oligo (dT) magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Cleaved short RNA fragments were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase and a random hexamer primer. Second-strand cDNA fragments were then synthesized using DNA polymerase I, RNase H, and dNTP. The cDNA fragments were ligated to sequencing adapters and amplified by PCR to obtain the final paired-end library. Library sequencing was performed on the Illumina sequencing platform (HiSeq 2500) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads.

Transcriptome data analysis

To analyze the RNA-Seq data, low-quality sequences were removed from the raw sequencing reads, and the adaptor sequences were trimmed using the Sequence CLEAN program. The remaining reads were called “clean reads” and stored in FASTQ format. The assembled unigenes were then mapped to mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) genome (GenBank: NM_001005484.1) using TopHat2 software [19]. After that, the transcripts were assembled with cufflinks [20]. Differences in gene expression levels were standardized by the reads per kilobase of unigene per million mapped reads (FPKM) method. The NOISeq [21] method was used to screen the differentially expressed genes (DEG) according to default criteria consisting in a |log2 Fold Change|> 1 and a p value < 0.05. Pathway annotation and enrichment analyses were performed using the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway databases. All presented data represent average changes in gene expression for 3 independent replicates.

Results

DTMUV replication in DEF

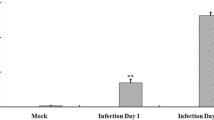

DTMUV infection in DEF was confirmed by cytopathic effects (CPE) and Western blot. First, the morphological changes in DTMUV-infected DEF were determined by microscopic observations 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 hpi. As shown in Figure 1A, we observed that DTMUV caused minimal CPE in DEF cells at 24 hpi. At 36, 48, and 60 hpi, compared with the morphology of the control cells, obvious cellular fragmentation and increased granularity were observed in the DTMUV-infected DEF. As shown in Figure 1B, the viral E protein expression was detected at 24 hpi, and greater expression was observed at 36, 48 and 60 hpi by Western blot.

DTMUV infection in DEF. A The cytopathic effects (CPE) of DEF after DTMUV infection at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 hpi, and mock infected cells as the control. B Western blot analysis was used to detect the expression of E protein in DTMUV-infected DEF and control cells. The protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The blots were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against DTMUV envelop protein E. The expression of β-actin was used as an internal control.

RNA sequencing and read assembly

To study DTMUV-DEF interactions, sequencing libraries were prepared in triplicate for 5 different time points after DEF were infected with DTMUV (12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 hpi) and were analyzed in comparison with uninfected cells at the corresponding time. In these experiments, an average of 47939795 clean sequencing reads were generated. After discarding ribosomal RNA and low-quality reads, 30 high-quality samples were further mapped onto the Anas platyrhynchos genome (GenBank accession: NM_001005484.1) using the TopHat2 software (Table 1). The average ratio of high-quality reads in comparison with the reference genome was 85.26%. Qualifying sample data were evaluated using multiple metrics (Table 1). The raw sequencing data have been deposited online in SRA at the NCBI under accession number (SRS6277135).

Global changes of gene expression after DTMUV infection

We use the volcano plot (Figure 2A) and histogram (Figure 2B) to evaluate the changes in the mRNA expression profile of DEF after DTMUV infection for 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 hpi (12 h Mock VS 12 hpi, 24 h Mock VS 24 hpi, 36 h Mock VS 36 hpi, 48 h Mock VS 48 hpi, 60 h Mock VS 60 hpi, 12 hpi VS 24 hpi, 24 hpi VS 36 hpi, 36 hpi VS 48 hpi, 48 hpi VS 60 hpi). At 12 h after DTMUV infection of DEF, there were 499 up-regulated genes and 182 down-regulated genes (Additional file 1); at 24 hpi, there were 1134 up-regulated genes and 515 down-regulated genes (Additional file 2); at 36 hpi, there were 1935 up-regulated genes and 1648 down-regulated genes (Additional file 3); at 48 hpi, there were 1998 up-regulated genes and 1824 down-regulated genes (Additional file 4); at 60 hpi, there were 2115 up-regulated genes and 2027 down-regulated genes (Additional file 5). In addition, a comparison of 24 hpi with 12 hpi shows that 590 genes were up-regulated and 91 genes were down-regulated. A comparison of 36 hpi with 24 hpi shows that there were 1064 up-regulated genes and 836 down-regulated genes. A comparison of 48 hpi with 36 hpi show that 373 genes were up-regulated and 415 genes were down-regulated 48 h after DTMUV infection and a comparison of 60 hpi with 48 hpi shows that 395 genes were up-regulated and 596 genes were down-regulated. We can see that after 36 h of DTMUV infection, the number of DEG increased significantly.

Changes of the gene expression in DEF at different times after DTMUV infection. A Volcano chart of differentially expressed genes (DEG). The x-axis shows the log2 (fold change) and y-axis shows the -log10 (p-value). Red dots represent the upregulated DEG, green dots represent the downregulated DEG and gray dots are the no significant difference genes (a. 12 h Mock VS 12 hpi; b. 24 h Mock VS 24 hpi; c. 36 h Mock VS 36 hpi; d. 48 h Mock VS 48 hpi; e. 60 h Mock VS 60 hpi; f. 12 hpi VS 24 hpi; g. 24 hpi VS 36 hpi; h. 36 hpi VS 48 hpi; i. 48 hpi VS 60 hpi). The vertical line in the figure is the two-fold expression difference threshold; the horizontal line is the p-value = 0.05 threshold. B The up-down statistical chart of the DEG.

Significantly differentially expressed transcripts and clustering

In order to more intuitively reflect the changes in DEG that accompany the process of viral infection, we established a Venn diagram to delve deeper into genes that are unique or shared during DTMUV infection (Figure 3A). The Venn diagram analysis revealed that 40 DEG were observed at all tested time points and that 230, 1174, 346 and 459 DEG were unique when comparing 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, and 48 and 60 hpi, respectively. In Figure 3A, genes that were differentially expressed at all time points were called continuous upregulated and downregulated genes and are marked with red circles; the DEG in this group undoubtedly play an important role during DTMUV infection. Hierarchical clustering was performed to compare a total of 40 DEG that were differentially expressed in DEF during different phases of DTMUV infection. Gradual changes in gene expression were observed between 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, and 48 and 60 hpi, and the left side of the hierarchical clustering gene tree allowed DEG to be further classified (Figure 3B).

Transcriptome data profile generated by Illumina HiSeqTM 2500 platform and differential expression analysis. A Venn diagram showing unique and co-differentially expressed genes in response to DTMUV infection at 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, and 48 and 60 hpi; B Hierarchical clustering analysis of co-differentially expressed genes at 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, and 48 and 60 hpi. The color in the heat map represents gene expression changes. Red indicates upregulation of gene expression, green indicates downregulation of expression.

GO analyses of DEG

A total of 3129 DEG were analyzed using the GO database at all the time points. The GO functional analysis resulted in 2797 GO terms being assigned to 12 and 24 hpi, including 320 GO terms in the cellular component (CC) category, 581 GO terms in the molecular functions (MF) category, and 1896 terms in the biological process (BP) category. A total of 5818 GO terms were assigned to 24 and 36 hpi, including 620 GO terms in the CC category, 1221 GO terms in the MF category, and 3977 GO terms in the BP category. A total of 3030 GO terms were assigned to 36 and 48 hpi, including 392 GO terms in the CC category, 696 GO terms in the MF category, and 1942 GO terms in the BP category. A total of 3506 GO terms were assigned to 48 and 60 hpi, including 418 GO terms in the CC category, 748 GO terms in the MF category, and 2340 GO terms in the BP category. Next, to select the most useful genes for further investigation, we chose the top 30 enriched GO terms, listed in Figures 4A–D.

Top 30 Gene ontology (GO) terms of DEG expressed in DTMUV-infected DEF. A GO annotation of DEG expressed at 12 and 24 hpi; B GO annotation of DEG expressed at 24 and 36 hpi; C GO annotation of DEG expressed at 36 and 48 hpi; D GO annotation of DEG expressed at 48 and 60 hpi. GO terms were classified into 3 categories, including cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF), and biological process (BP). The top 30 GO terms were selected according to p-value < 0.05.

KEGG pathway analysis of DEG

The KEGG database is used for the pathway-based classification of orthologous genes to provide useful information for predicting biological processes and phenotypic traits of genes. To determine the various biological processes involved in an DTMUV infection, 3129 DEG were mapped to referential canonical signaling pathways via KEGG database analysis. Of the differentially expressed DEF genes observed by comparing the 12 and 24 hpi, 188 DEG were mapped to 112 KEGG pathways. When comparing the 24 and 36 hpi, 554 DEG were mapped to 148 KEGG pathways. When comparing the 36 and 48 hpi, 230 DEG were mapped to 114 KEGG pathways. Finally, when comparing the 48 and 60 hpi, 288 DEG were mapped to 115 KEGG pathways. Next, we selected the top 20 most enriched KEGG pathways at all different time points according to a p-value < 0.05, as shown in Figures 5A–D. In addition, we screened out important DEG related to viral invasion (Additional file 6) and host cell defense pathways (Additional file 7).

Discussion

Although many researchers have undertaken extensive efforts to understand flavivirus infection in human cells, little is known about DTMUV infection in avian-derived cells. As an economically important disease of the poultry industry, DTMUV has a broad host range and causes reduced egg production in ducks, leading to substantial economic losses [8]. However, little information has been reported on the molecular mechanism underlying the host-DTMUV interaction. In this study, we employed high-throughput RNA-Seq technology and explored important information about host-virus interaction at 5 characteristic stages (12, 24, 36, 48 and 24 hpi) of DTMUV-infected DEF.

After DTMUV infection, the viruses first adhere to the cell surface and bind to specific receptors, a step that is considered a prelude to viral infection, and then enter the cell through endocytosis. Similarly, our study also detected the differential expression of CAV3, PML, AMPH, GRK7, WIPF3 and DAB2, which are associated with the endocytosis pathway induced by DTMUV (Figures 6 and 7). Then, we found that CGN, MAP3K5, GATA4 and RUNX1 related to tight junction were upregulated during DTMUV infection, indicating that these genes may play an important role in DTMUV entry.

Expression profiles (heat map) of virus infection genes at 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, 48 and 60 hpi. The color in the heat map represents gene expression changes (red, high gene expression; green, low gene expression; black, no gene expression). DEG are labeled on the right of the heat-map, DEG clusters are labeled on the left of the heat-map.

Expression profiles (heat map) of host cells immune defense genes at 12 and 24 hpi, 24 and 36 hpi, 36 and 48 hpi, 48 and 60 hpi. The color in the heat map represents gene expression changes (red, high gene expression; green, low gene expression; black, no gene expression). DEG are labeled on the right of the heat-map, DEG clusters are labeled on the left of the heat-map.

The suppression of host cell growth is an important indicator of flavivirus infection [22,23,24]. In our study, we observed that the expression of cell cycle-associated DEG (GADD48B and GADD45G) was significantly downregulated at 48 and 60 hpi (Figure 6), indicating that the decreased expression of these genes may facilitate DTMUV replication. Most of the genes involved in the proinflammatory response were downregulated during DTMUV infection at 48 and 60 hpi (Figure 7), suggesting that flavivirus gene expression interfered with host cell antiviral defense mechanisms [25, 26]. Apoptosis is a critical defense mechanism in many organisms. Direct or indirect inhibition of apoptosis can facilitate viral infections [27, 28]. Moreover, some virus-induced apoptosis can enhance the spread of the virus, leading to tissue damage and disease. A previous morphological study revealed that DTMUV infection could cause apoptosis in DEF [8]. However, the molecular mechanism by which apoptosis is induced by DTMUV infection remains unclear. In this study, the IGF1, which regulates cell growth and proliferation, acting as a potent inhibitor of apoptosis [29], was clearly downregulated during DTMUV infection (Figure 6). Our results may be related to the facilitation of DTMUV infection. Future verification of the role of the IGF1 gene in regulating apoptosis in DTMUV-infected host cells is necessary.

To accomplish viral replication, assembly, and maturation, intracellular complexes of the virus utilize intracellular cytoskeletal components of the host to move from the periphery of the cell to sites of RNA synthesis [30]. Microtubules and actin are important components of the cellular cytoskeleton that facilitates flavivirus intracellular translocation to the nucleus [31,32,33]. In our study, we observed that DTMUV-infected DEF included a number of upregulated DEG that regulate the action cytoskeleton signaling pathway, such as FGF (fibroblast growth factor) family members (FGF1/3/4/5/19) and scaffold protein IQGAP2, which play a role in stabilizing microtubules [34,35,36] (Figure 6). Then, we found that tight junction (CGN, MAP3K5, GATA4 and RUNX1) and focal adhesion (KDR, LAMA3, LAMC2, PTK2, COL6A6 and COL4A3) play important roles in DTMUV replication, which is similar to the reports of flavivirus [37, 38].

Upon DTMUV infection, host defense against viral infections occurs via several different mechanisms, primarily involving the innate immune response at early time points and shifting to adaptive immune responses at later time points. The innate immune response is activated by pattern recognition receptors that recognize conserved microbial molecules known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns, constituting an early line of defense [39]. In our study, as a result of DTMUV invasion, the Nod-like receptor pathway (P2RX7, TMEM173 and IL6), the Toll-like receptor pathway (TLR7, CD86, IL6 and IL12B), and the RIG-I-like receptor pathway (TMEM173 and IL12B) were activated (Figure 7). In a recent study, Han et al. [40] found that the host innate immune system was also activated after DTMUV infection of DF-1 cells, including TLR pathway, RLR receptor pathway, NLR pathway and JAK-STAT pathway. Also, they found that numerous critical molecules in the TLR, RLR and NLR pathways were upregulated, such as TLR3, IRF7, STAT1, IFN-α and IFN-β. The ubiquitin—proteasome system (UPS) is the major degradation system in the host cells, also playing an important role in the different stages of the virus life cycle, including viral adsorption, viral penetration and uncoating, gene transcription, protein synthesis, assembly, and viral progeny release. Interestingly, Han et al. found that some UPS-related DEG (TRIM36, DTX3L, MYLIP, RNF185, TRIM25, and RNF19β) were significantly upregulated during DTMUV infection by RNA-seq technology, which may be related to their previous finding that UPS is involved in DTMUV replication [41].

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns are recognized by pattern recognition receptors, triggering a downstream signaling cascade and a proinflammatory response that includes cytokines, chemokines, and tumor necrosis factor [39, 42]. Our results indicate that the expression of IL6, IL12B, IL1R2, IL23R, IL12RB1 and IL12RB2 increased after DTMUV infection (Figure 7). IL6 and IL12B are 2 important inflammatory factors that are upregulated in DTMUV [43, 44]. However, dysregulated expression of IL6 or IL12B can cause several inflammatory diseases and death [45]. Additionally, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a pleiotropic cytokine that produces a wide range of stimuli. TNFSF4/5/10 and TNFRSF4/8/9/13B were influenced during DTMUV infection and all these factors function as important proinflammatory genes and play vital roles in the inflammatory response [46, 47]. These results indicate that these important proinflammatory responses may activate the innate immune response and promote viral clearance. Further studies examining the mechanism underlying cytokine regulation in DTMUV-infected cells are necessary.

It is well accepted that complete clearance of intracellular viruses requires the destruction of infected cells by the adaptive immune system [48]. To the best of our knowledge, the phagosome plays an important role in balancing microbicidal and proteolytic degradation functions with the generation of antigenic peptides for presentation by MHCI and MHCII molecules to CD8 and CD4 T cells [49]. We found that the genes (ATP6V1G3, MARCO, TAP1, THBS4 and TUBB1) involved in the formation of phagosomes are up-regulated to varying degrees after DTMUV infection. MHCII molecules are transported to the plasma membrane and present viral peptides to CD4+ cells [50], and CD36 is required for proper MHCII antigen pentation [51, 52]. Our results indicate that CD36 and CTSS (the basic components of MHCII) were upregulated in DTMUV-infected cells, indicating that DTMUV has the potential to be presented to CD4 cells and evoke a host adaptive immune response as a defense against DTMUV infection. In addition, COLEC11, which is involved in the activation of the complement system, was also significantly up-regulated. Therefore, based on our study results, we infer that activation of the complement system and antigen presentation by DTMUV infection in DEF might serve as a link between the innate and adaptive immune responses to facilitate an integrated host response [53]. In addition, activation of the complement system and antigen presentation can help to increase the level of specific immune responses, providing new ideas for the design and development of new vaccines or vaccine adjuvants in the future.

This RNA-Seq study offers new insights and provides potential research targets for a better understanding of the DEF response to DTMUV infection. Our data highlight how viral infection relates to host defensive responses during virus infection. In a broader sense, the basic data obtained in this study are a valuable resource that provide a preliminary but comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the molecular mechanisms of the host-DTMUV interaction and provide new ideas for vaccine development.

Availability of data and materials

The read sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number SRS6277135.

Abbreviations

- DTMUV:

-

duck Tembusu virus

- hpi:

-

hour post-infection

- DEFs:

-

duck embryo fibroblasts

- DEGs:

-

differentially expressed genes

- MOI:

-

multiplicity of infection

- FPKM:

-

per kilobase of unigene per million mapped reads

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- CPE:

-

cytopathic effects

- CC:

-

cellular component

- MF:

-

molecular functions

- BP:

-

biological process

- FGF:

-

fibroblast growth factor

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor alpha

References

Lei W, Guo X, Fu S, Feng Y, Tao X, Gao X, Song J, Yang Z, Zhou H, Liang G (2017) The genetic characteristics and evolution of Tembusu virus. Vet Microbiol 201:32–41

Su J, Li S, Hu X, Yu X, Wang Y, Liu P, Lu X, Zhang G, Hu X, Liu D, Li X, Su W, Lu H, Mok NS, Wang P, Wang M, Tian K, Gao GF (2011) Duck egg-drop syndrome caused by BYD virus, a new Tembusu-related flavivirus. PLoS One 6:e18106

Thontiravong A, Ninvilai P, Tunterak W, Nonthabenjawan N, Chaiyavong S, Angkabkingkaew K, Mungkundar C, Phuengpho W, Oraveerakul K, Amonsin A (2015) Tembusu-related flavivirus in ducks, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis 21:2164–2167

Yan P, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Xu D, Dai X, Teng Q, Yan L, Zhou J, Ji X, Zhang S, Liu G, Zhou Y, Kawaoka Y, Tong G, Li Z (2011) An infectious disease of ducks caused by a newly emerged Tembusu virus strain in mainland China. Virology 417:1–8

Zhang W, Chen S, Mahalingam S, Wang M, Cheng A (2017) An updated review of avian-origin Tembusu virus: a newly emerging avian flavivirus. J Gen Virol 98:2413–2420

He Y, Wang A, Chen S, Wu Z, Zhang J, Wang M, Jia R, Zhu D, Liu M, Yang Q, Wu Y, Sun K, Chen X, Cheng A (2017) Differential immune-related gene expression in the spleens of duck Tembusu virus-infected goslings. Vet Microbiol 212:39–47

Tang Y, Diao Y, Yu C, Gao X, Ju X, Xue C, Liu X, Ge P, Qu J, Zhang D (2013) Characterization of a Tembusu virus isolated from naturally infected house sparrows (Passer domesticus) in Northern China. Transbound Emerg Dis 60:152–158

Pan Y, Cheng A, Zhang X, Wang M, Chen S, Zhu D, Liu M, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, Huang J, Zhang S, Mao S, Ou X, Gao Q, Yu Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yin Z, Jing B, Tian B, Pan L, Rehman MU, Chen X, Jia R (2020) Transcriptome analysis of duck embryo fibroblasts for the dynamic response to duck tembusu virus infection and dual regulation of apoptosis genes. Aging 12:17503–17527

Tang Y, Gao X, Diao Y, Feng Q, Chen H, Liu X, Ge P, Yu C (2013) Tembusu virus in human, China. Transbound Emerg Dis 60:193–196

Yu G, Lin Y, Tang Y, Diao Y (2018) Evolution of Tembusu virus in ducks, chickens, geese, sparrows, and mosquitoes in Northern China. Viruses 10:485

Zhang W, Jiang B, Zeng M, Duan Y, Wu Z, Wu Y, Wang T, Wang M, Jia R, Zhu D, Liu M, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, Zhang S, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yu Y, Pan L, Chen S, Cheng A (2020) Binding of duck Tembusu virus nonstructural protein 2A to duck STING disrupts induction of its signal transduction cascade to inhibit beta interferon induction. J Virol 94:e01850–19

Wu Z, Zhang W, Wu Y, Wang T, Wu S, Wang M, Jia R, Zhu D, Liu M, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, Zhang S, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yu Y, Pan L, Merits A, Chen S, Cheng A (2019) Binding of the duck Tembusu virus protease to STING is mediated by NS2B and is crucial for STING cleavage and for impaired induction of IFN-β. J Immunol 203:3374–3385

Seong R-K, Lee JK, Cho GJ, Kumar M, Shin OS (2020) mRNA and miRNA profiling of Zika virus-infected human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells identifies miR-142-5p as an antiviral factor. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:2061–2075

Poonpanichakul T, Chan-In W, Opasawatchai A, Loison F, Matangkasombut O, Charoensawan V, Matangkasombut P (2021) Innate lymphoid cells activation and transcriptomic changes in response to human dengue infection. Front Immunol 12:599805

Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M (2009) RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet 10:57–63

Adams S, Xing Z, Li J, Mendoza K, Perez D, Reed K, Cardona C (2013) The effect of avian influenza virus NS1 allele on virus replication and innate gene expression in avian cells. Mol Immunol 56:358–368

Zhu K, Huang J, Jia R, Zhang B, Wang M, Zhu D, Chen S, Liu M, Yin Z, Cheng A (2015) Identification and molecular characterization of a novel duck Tembusu virus isolate from Southwest China. Arch Virol 160:2781–2790

Chen S, He Y, Zhang R, Liu P, Yang C, Wu Z, Zhang J, Wang M, Jia R, Zhu D, Liu M, Yang Q, Wu Y, Cheng A (2018) Establishment of a reverse genetics system for duck Tembusu virus to study virulence and screen antiviral genes. Antiviral Res 157:120–127

Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, Kołodziejczyk AA, Zhang X, Proserpio V, Baying B, Benes V, Teichmann SA, Marioni JC, Heisler MG (2013) Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nat Methods 10:1093–1095

Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28:511–515

Tarazona S, García-Alcalde F, Dopazo J, Ferrer A, Conesa A (2011) Differential expression in RNA-seq: a matter of depth. Genome Res 21:2213–2223

Choksupmanee O, Tangkijthavorn W, Hodge K, Trisakulwattana K, Phornsiricharoenphant W, Narkthong V, Tulakarnwong S, Ngamphiw C, Tongsima S, Chimnaronk S (2021) Specific interaction of DDX6 with an RNA hairpin in the 3-UTR of the Dengue genome mediates G1 phase arrest. J Virol 95:e0051021

Hammack C, Ogden SC, Madden JC, Medina A, Xu C, Philips E, Son Y, Cone A, Giovinazzi S, Didier RA, Gilbert DM, Song H, Ming G, Wen Z, Brinton MA, Gunjan A, Tang H (2019) Zika virus infection induces DNA damage response in human neural progenitors that enhances viral replication. J Virol 93:e00638–e19

Kim JY, Park SY, Lyoo HR, Koo ES, Kim MS, Jeong YS (2015) Extended stability of cyclin D1 contributes to limited cell cycle arrest at G1-phase in BHK-21 cells with Japanese encephalitis virus persistent infection. J Microbiol 53:77–83

Riedl W, Acharya D, Lee JH, Liu G, Serman T, Chiang C, Chan YK, Diamond M, Gack MU (2019) Zika virus NS3 mimics a cellular 14–3–3-binding motif to antagonize RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe 26:493–503

Xia H, Luo H, Shan C, Muruato AE, Nunes B, Medeiros D, Zou J, Xie X, Giraldo MI, Vasconcelos P, Weaver SC, Wang T, Rajsbaum R, Shi PY (2018) An evolutionary NS1 mutation enhances Zika virus evasion of host interferon induction. Nat Commun 9:414

Brune W (2010) Inhibition of programmed cell death by cytomegaloviruses. Virus Res 157:144–150

Li J, Huang R, Liao W, Chen Z, Zhang S, Huang R (2012) Dengue virus utilizes calcium modulating cyclophilin-binding ligand to subvert apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 418:622–627

Zhang QC, Zou YP, Hu SQ, Zhang TW, Zhou H, Liang B, Zhuang CY, Wang HR, Jiang LB, Li XL (2021) TNF-α-stimulated nucleus pulposus cells induce cell apoptosis through the release of exosomal miR-16 targeting IGF-1 and IGF-1R in rats. Ann Transl Med 9:1376

Marsh M, Helenius A (2006) Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124:729–740

Nie Y, Hui L, Guo M, Yang W, Huang R, Chen J, Wen X, Zhao M, Wu Y (2021) Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton by Zika virus infection facilitates blood-testis barrier hyperpermeability. Virol Sin 36:692–705

Whelan JN, Parenti NA, Hatterschide J, Renner DM, Li Y, Reyes HM, Dong B, Perez ER, Silverman RH, Weiss SR (2021) Zika virus employs the host antiviral RNase L protein to support replication factory assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118:e2101713118

Zhang Y, Gao W, Li J, Wu W, Jiu Y (2019) The role of host cytoskeleton in flavivirus infection. Virol Sin 34:30–41

Li J, Wang Q, Wang H, Wu Y, Yin J, Chen J, Zheng Z, Jiang T, Xie L, Wu F, Zhang H, Li X, Xu H, Xiao J (2018) Lentivirus mediating FGF13 enhances axon regeneration after spinal cord injury by stabilizing microtubule and improving mitochondrial function. J Neurotrauma 35:548–559

Wu QF, Yang L, Li S, Wang Q, Yuan XB, Gao X, Bao L, Zhang X (2012) Fibroblast growth factor 13 is a microtubule-stabilizing protein regulating neuronal polarization and migration. Cell 149:1549–1564

Kothari P, Srivastava V, Aggarwal V, Tchernyshyov I, Van Eyk JE, Ha T, Robinson DN (2019) Contractility kits promote assembly of the mechanoresponsive cytoskeletal network. J Cell Sci 132:jcs226704

Pan P, Li G, Shen M, Yu Z, Ge W, Lao Z, Fan Y, Chen K, Ding Z, Wang W, Wan P, Shereen MA, Luo Z, Chen X, Zhang Q, Lin L, Wu J (2021) DENV NS1 and MMP-9 cooperate to induce vascular leakage by altering endothelial cell adhesion and tight junction. PLoS Pathog 17:e1008603

Wang S, Zhang Q, Tiwari SK, Lichinchi G, Yau EH, Hui H, Li W, Furnari F, Rana TM (2020) Integrin αvβ5 internalizes Zika virus during neural stem cells infection and provides a promising target for antiviral therapy. Cell Rep 30:969–983

Takeuchi O, Akira S (2010) Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140:805–820

Han K, Zhao D, Liu Q, Liu Y, Huang X, Yang J, Zhang L, Li Y (2021) Transcriptome analysis reveals new insight of duck Tembusu virus (DTMUV)-infected DF-1 cells. Res Vet Sci 137:150–158

Han K, Zhao D, Liu Y, Liu Q, Huang X, Yang J, Zhang L, Li Y (2019) The ubiquitin-proteasome system is necessary for the replication of duck Tembusu virus. Microb Pathog 132:362–368

Mogensen TH (2009) Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:240–273

Li N, Wang Y, Li R, Liu J, Zhang J, Cai Y, Liu S, Chai T, Wei L (2015) Immune responses of ducks infected with duck Tembusu virus. Front Microbiol 6:425

Yu G, Lin Y, Tang Y, Diao Y (2018) Comparative transcriptomic analysis of immune-related gene expression in duck embryo fibroblasts following duck Tembusu virus infection. Int J Mol Sci 19:2328

Frey N, Grange S, Woodworth T (2010) Population pharmacokinetic analysis of tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Pharmacol 50:754–766

Fan H, Lu B, Cao C, Li H, Yang D, Huang L, Ding T, Wu M, Lu G (2020) Plasma TNFSF13B and TNFSF14 function as inflammatory indicators of severe adenovirus pneumonia in pediatric patients. Front Immunol 11:614781

Kucka K, Wajant H (2020) Receptor oligomerization and its relevance for signaling by receptors of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:615141

Nikolich-Žugich J (2018) The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat Immunol 19:10–19

Ramachandra L, Simmons D, Harding CV (2009) MHC molecules and microbial antigen processing in phagosomes. Curr Opin Immunol 21:98–104

Helft J, Böttcher J, Chakravarty P, Zelenay S, Huotari J, Schraml BU, Goubau D, Reis e Sousa C, (2015) GM-CSF mouse bone marrow cultures comprise a heterogeneous population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunity 42:1197–1211

Schulz O, Pennington DJ, Hodivala-Dilke K, Febbraio M, Reis e Sousa C, (2002) CD36 or alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 integrins are not essential for MHC class I cross-presentation of cell-associated antigen by CD8 alpha+ murine dendritic cells. J Immunol 168:6057–6065

Belz GT, Vremec D, Febbraio M, Corcoran L, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Heath WR (2002) CD36 is differentially expressed by CD8+ splenic dendritic cells but is not required for cross-presentation in vivo. J Immunol 168:6066–6070

Afshar-Kharghan V (2017) The role of the complement system in cancer. J Clin Invest 127:780–789

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the technology and methodology of transcriptome sequencing provided by Oebiotech (Shanghai, China).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172833), Sichuan Veterinary Medicine and Drug Innovation Group of China Agricultural Research System (CARS-SVDIP), and China Agricultural Research System (CARS-42–17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, YP and XW; methodology, YP and XW; software, YP and WC; validation, RJ; formal analysis, YP; investigation, YP; resources, SC, DZ, ML, XZ, SZ, DS and ZY; data curation, YP; writing-original draft preparation, YP; writing-review and editing, RJ; visualization, QY, YW, JH, SM, XO, QG and BT; supervision, RJ; project administration, RJ and AC; funding acquisition, RJ, AC and MW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University, Sichuan, China and followed the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the performance of animal experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Y., Wu, X., Cai, W. et al. RNA-Seq analysis of duck embryo fibroblast cells gene expression during duck Tembusu virus infection. Vet Res 53, 34 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01051-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01051-y