Abstract

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (Salmonella Typhimurium) contamination of pork, is one of the major sources of human salmonellosis. The bacterium is able to persist and hide in asymptomatic carrier animals, generating a reservoir for Salmonella transmission to other animals and humans. Mechanisms involved in Salmonella persistence in pigs remain poorly understood. In the present study, we demonstrate that the Salmonella htpG gene, encoding a homologue of the eukaryotic heat shock protein 90, contributes to Salmonella Typhimurium persistence in intestine-associated tissues of pigs, but not in the tonsils. HtpG does not seem to play an important role during the acute phase of infection. The contribution to persistence was shown to be associated with htpG-dependent Salmonella invasion and survival in porcine enterocytes and macrophages. These results reveal the role of HtpG as a virulence factor contributing to Salmonella persistence in pigs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salmonellosis is regarded as one of the most important bacterial zoonotic diseases [1, 2]. The main route of human infection is through the consumption of contaminated food, such as pork, with Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (Salmonella Typhimurium) being the most frequently isolated serovar from slaughter pigs [3]. Salmonella Typhimurium seldom produces systemic infections in healthy adult animals. The bacterium is however able to colonize the alimentary tract and may cause acute enteritis followed by persistence. The ability to cause a persistent colonization in the host is a major characteristic of Salmonella virulence [4]. Persistence is here defined as a chronic presence of Salmonella Typhimurium in the porcine host. In our infection model [5] as well as in practice, this is characterized by relatively high level infection loads in tonsils but low intestinal loads resulting in intermittent faecal shedding. Persistently colonized carrier animals are difficult to distinguish from uninfected pigs and they constitute a continuous reservoir of Salmonella bacteria. During periods of stress, like transport to the slaughter house, a flare up of this asymptomatic colonization may occur [6]. Until now, the mechanism of prolonged colonization in carrier pigs remains poorly known, which seriously hampers the development of efficient mitigation measures. A thorough understanding of how Salmonella is able to persist requires the identification of bacterial genes involved.

Recently, using in vivo expression technology (IVET), Van Parys et al. identified 37 Salmonella Typhimurium genes that are specifically expressed during persistence in pigs [7]. Although these are potential virulence genes, their individual contribution to Salmonella persistence remains to be further explored. In the present study, we focused on one of these 37 genes, the htpG gene that encodes a homologue of the eukaryotic heat shock protein 90 (hsp90), a chaperone being important for the maintenance, activation, stabilization or maturation of proteins [8]. The aim of this study was to define the role of this gene during colonization and persistence of Salmonella Typhimurium in pigs.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

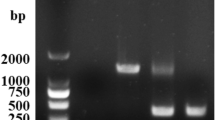

Salmonella Typhimurium strain 112910a phage type 120/ad, isolated from a pig stool sample, was used as the wild type strain (WT). A spontaneous nalidixic acid resistant derivative of the wild type strain was used in the in vivo experiment (Salmonella WTnal). Salmonella Typhimurium deletion (Salmonella ΔhtpG) and kanamycin resistant substitution (Salmonella ΔhtpG:kanR) mutants (Table 1) were constructed according to the one-step inactivation method as described previously [9] and slightly modified for use in Salmonella Typhimurium [10].

Cell cultures and experiments

Invasion and intracellular survival of Salmonella was quantified in porcine intestinal epithelial cells (IPEC-J2) and in porcine macrophages. IPEC-J2 cells [11, 12] and primary porcine alveolar macrophages (PAM) [13] were cultured as previously described. To examine whether the ability of Salmonella Typhimurium to invade and proliferate in PAM and IPEC-J2 cells was altered after deletion of htpG, gentamicin protection assays were performed using Salmonella WT and Salmonella ΔhtpG. Therefore, PAM and IPEC-J2 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of approximately 106 and 5 × 105 cells per well, respectively. PAM were allowed to attach for 2 h and IPEC-J2 cells were allowed to grow for 24 h. Subsequently, Salmonella was inoculated into the wells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1. To synchronize the infection, the inoculated multiwell plates were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After washing the cells three times with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), they were supplemented for 1 h with fresh medium containing 100 µg/mL gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. After washing 3 times, the cells were lysed for 10 min with 1% Triton X-100 or 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, respectively. The number of invaded Salmonella bacteria was determined by plating 10-fold dilutions on Brilliant Green Agar (BGA) plates. To assess intracellular proliferation, the medium containing 100 µg/mL gentamycin was replaced after 1 h with fresh medium containing 20 µg/mL. The plates were incubated for 6 or 24 h and the number of intracellular bacteria was determined as described for the invasion.

Role of htpG during persistence of Salmonella in pigs

The animal experiment was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendation in the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes. The experimental protocols and care of the animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University (EC2010/005). Thirteen four-week-old piglets (commercially closed line based on Landrace) from a serologically Salmonella negative breeding herd were used. The Salmonella-free status of the piglets was verified serologically (IDEXX, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands) and bacteriologically via repeated faecal sampling. The animals arrived at the facility 5 days before inoculation and they were housed in isolation units at 25 °C under natural day-night rhythm in HEPA-filtered stables, with ad libitum feed and water. The piglets were randomly divided in a negative control group of 3 animals and 2 groups of 5 animals that were orally inoculated with a mixture of approximately 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Salmonella WTnal and 2 × 107 CFU Salmonella ΔhtpG:kanR. The negative control pigs were administered 2 mL HBSS. It was our hypothesis that htpG contributes to persistence but that deleting this gene does not result in a lack of successful initial colonization of the pig. Based on the results of Boyen et al., we determined the Salmonella numbers at day 4 (acute phase) and day 21 (persistent phase) in this experiment [5]. Therefore, one group of Salmonella-inoculated animals was euthanized 4 days post inoculation (pi). The negative control and the other Salmonella-inoculated group were euthanized 3 weeks pi. Samples of the palatine tonsils, ileum and contents, ileocecal lymph nodes, cecum and contents and faeces were collected and bacteriologically analyzed as previously explained [6]. Briefly, 10% suspensions of all samples were prepared in buffered peptone water and the number of Salmonella bacteria was determined by plating 10-fold dilutions on BGA plates supplemented with 20 µg/mL nalidixic acid or 100 µg/mL kanamycin. Samples that were negative after direct plating but positive after enrichment in tetrathionate broth were presumed to contain 83 CFU per gram sample (detection limit for direct plating).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of the data was assessed using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test to address the significance of difference between mean values with significance set at P ≤ 0.05. If equal variances were not assessed or if the data were not normally distributed, they were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis analysis, followed by a Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

HtpG plays a role during intestinal persistence of Salmonella Typhimurium in pigs

Four days pi, no significant differences were observed in the number of Salmonella WTnal and Salmonella ΔhtpG:kanR bacteria colonizing the tonsils, ileocecal lymph nodes, ileum and cecum and their contents and faeces (Figure 1A). In contrast, 21 days pi, significant differences in colonization were noticed between the two strains (Figure 1B). The Salmonella ΔhtpG:kanR strain was attenuated in the intestine-associated tissues and contents: ileocecal lymph nodes (decrease of 1.2 log10 (CFU/g)), ileum (decrease of 1.1 log10 (CFU/g)), cecum (decrease of 0.5 log10 (CFU/g)), ileum contents (decrease of 1.3 log10 (CFU/g)), cecal contents (decrease of 1.8 log10 (CFU/g)) and faeces (decrease of 0.3 log10 (CFU/g)). These differences were significant in the ileocecal lymph nodes (p = 0.042) and cecal contents (p = 0.018).

Salmonella Typhimurium WT nal and Δ htpG:kanR colonization of pigs. Recovery of bacteria from various organs of 5 piglets orally inoculated with an equal mixture of Salmonella WTnal and ΔhtpG:kanR, A 4 days pi and B 21 days pi. The log 10 value of the number of CFU per gram sample is given as the mean + standard deviation. A non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was performed and superscript (*) refers to a significant difference compared to the wild type Salmonella group (p < 0.05).

HtpG is involved in invasion and intracellular replication of Salmonella in macrophages

In IPEC-J2 cells, we observed a tendency (p < 0.1) towards reduced invasion (decrease of 0.1 log10 (CFU/mL)) and intracellular survival for 24 h (decrease of 0.4 log10 (CFU/mL)) of Salmonella ΔhtpG compared to the WT strain (Figure 2A). Moreover, the htpG gene was also shown to be important (p < 0.05) for Salmonella invasion (decrease of 0.1 log10 (CFU/mL)) and survival capacities at 6 h pi (decrease of 0.2 log10 (CFU/mL)) and 24 h pi (decrease of 0.3 log10 (CFU/mL)) in primary macrophages, in vitro (Figure 2B).

Role of htpG during invasion and intracellular replication of Salmonella in host cells. Number of intracellular Salmonella WT or ΔhtpG bacteria after invasion or intracellular replication (6 and/or 24 h) in A IPEC-J2 cells or B primary macrophages. The log10 values of the number of gentamicin protected bacteria + standard deviation are shown. Results are presented as a representative experiment conducted in sixfold. An independent t-test was performed and superscript (*) refers to a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The pathogenicity of Salmonella has been extensively studied, both in vitro and in vivo, using different animal models like the mouse, pig and chicken. Especially the mouse model is a widely used paradigm for studying the pathogenesis of systemic disease caused by Salmonella. However, investigations concerning food safety should employ natural hosts to examine gastrointestinal colonization by Salmonella. A major source of Salmonella contamination of pork meat is cross-contamination in the slaughterhouse. A thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms that Salmonella Typhimurium exploits to persist in the tonsils, gut and gut-associated lymphoid tissues, might contribute to the development of appropriate measures to minimize Salmonella contamination of porcine carcasses. Therefore, in the past decade, research has focused on the identification of virulence mechanisms contributing to its persistence in pigs. However, up to date, few data are available concerning Salmonella persistence in pigs [7, 14–17].

Persistence of Salmonella is an intriguing characteristic of the bacterium that allows maintenance of the pathogen in a host population. After bacterial invasion in hosts, such as pigs, the immune system will respond to clear the infection and bacterial survival strategies for persistence will become important. We now showed that the htpG gene encodes such a survival mechanism. Deletion of the htpG gene does not affect the acute phase of infection, but reduces the survival capacity of the bacterium in intestine-associated tissues of pigs. The specific role of HtpG in bacterial pathogenesis is largely unknown, but it is a homolog of the eukaryotic chaperone hsp90, being important in the adaptation of Salmonella to stress conditions [18]. During persistence in a certain host, Salmonella has to deal with numerous stresses, like the host’s immune system, decreased oxygen tension, nutrient limitation and starvation and shift in temperature and pH. Possibly, the HtpG chaperone helps Salmonella dealing with stressful events during persistence, in vitro and in vivo, leading to an increased survival of the bacterium.

In the past, using IVET, Van Parys et al. screened the tonsils, ileum and ileocecal lymph nodes for genes being induced during the persistent phase of colonization [7]. They showed that the htpG gene is expressed in all three organs [7]. However, we now demonstrated that the htpG gene plays a role during persistence of the bacterium in intestine-associated tissues of pigs but not in the tonsils. In contrast to the gut and gut-associated lymphoid tissue, Salmonella resides largely in an extracellular niche in the tonsils [19]. Therefore, virulence mechanisms necessary for cell invasion and intracellular survival do not contribute to tonsillar colonization and persistence [17, 20]. We also showed that Salmonella Typhimurium lacking htpG was impaired in invasion and intracellular replication in epithelial cells and macrophages. Invasion of gut epithelial cells and the capacity to survive and replicate intracellularly in macrophages are major factors contributing to intestinal Salmonella Typhimurium persistence in pigs. Our findings, therefore, confirm the earlier hypothesis that different molecular mechanisms are involved in Salmonella colonization of and persistence in the tonsils on one hand, and in the gut and gut-associated lymphoid tissue on the other hand [17, 19, 20]. Although Salmonella persistence in tonsils represents a major factor in persistence of the bacterium in pigs, the bacterial genes involved remain largely unknown.

Based on the results obtained by Boyen et al., we sacrificed pigs 3 weeks post inoculation and used this model to examine Salmonella persistence in pigs [5]. Although its contribution to long-term (several months) persistence is not clear, we can conclude that htpG contributes to Salmonella Typhimurium persistence in the porcine intestine until 3 weeks after inoculation.

References

Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED (2004) The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull World Health Organ 82:346–353

Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O’Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A, Hoekstra RM (2010) The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis 50:882–889

Pires SM, de Knegt L, Hald T (2011) Scientific/technical report submitted to EFSA on an estimation of the relative contribution of different food and animal sources to human Salmonella infections in the European Union. Report to contract CT/EFSA/Zoonoses/2010/02. National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark, p 80

Wood RL, Rose R, Coe NE, Ferris KE (1991) Experimental establishment of persistent infection in swine with a zoonotic strain of Salmonella Newport. Am J Vet Res 52:813–819

Boyen F, Pasmans F, Donné E, Van Immerseel F, Morgan E, Adriaensen C, Hernalsteens JP, Wallis TS, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F (2006) The fibronectin binding protein ShdA is not a prerequisite for long term faecal shedding of Salmonella Typhimurium in pigs. Vet Microbiol 115:284–290

Verbrugghe E, Boyen F, Van Parys A, Van Deun K, Croubels S, Thompson A, Shearer N, Leyman B, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F (2011) Stress induced Salmonella Typhimurium recrudescence in pigs coincides with cortisol induced increased intracellular proliferation in macrophages. Vet Res 42:118

Van Parys A, Boyen F, Leyman B, Verbrugghe E, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans P (2011) Tissue-specific Salmonella Typhimurium gene expression during persistence in pigs. PLoS One 6:e24120

Yosef I, Goren MG, Kiro R, Edgar R, Qimron U (2011) High-temperature protein G is essential for activity of the Escherichia coli clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20136–20141

Datsenko KA, Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645

Boyen F, Pasmans F, Donné E, Van Immerseel F, Adriaensen C, Hernalsteens JP, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F (2006) Role of SPI-1 in the interactions of Salmonella Typhimurium with porcine macrophages. Vet Microbiol 113:35–44

Rhoads JM, Chen W, Chu P, Berschneider HM, Argenzio RA, Paradiso AM (1994) L-glutamine and l-asparagine stimulate Na+-H+ exchange in porcine jejunal enterocytes. Am J Physiol 266:828–838

Schierack P, Nordhoff M, Pollmann M, Weyrauch KD, Amasheh S, Lodemann U, Jores J, Tachu B, Kleta S, Blikslager A, Tedin K, Wieler LH (2006) Characterization of a porcine intestinal epithelial cell line for in vitro studies of microbial pathogenesis in swine. Histochem Cell Biol 125:293–305

Dom P, Haesebrouck F, De Baetselier P (1992) Stimulation and suppression of the oxygenation activity of porcine pulmonary alveolar macrophages by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and its metabolites. Am J Vet Res 53:1113–1118

Bearson SM, Bearson BL, Rasmussen MA (2006) Identification of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium genes important for survival in the swine gastric environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2829–2836

Bearson BL, Bearson SM (2008) The role of the QseC quorum-sensing sensor kinase in colonization and norepinephrine-enhanced motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb Pathog 44:271–278

Bearson SM, Bearson BL, Brunelle BW, Sharma VK, Lee IS (2011) A mutation in the poxA gene of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium alters protein production, elevates susceptibility to environmental challenges, and decreases swine colonization. Foodborne Pathog Dis 8:725–732

Boyen F, Pasmans F, Van Immerseel F, Morgan E, Botteldoorn N, Heyndrickx M, Volf J, Favoreel H, Hernalsteens JP, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F (2008) A limited role for SsrA/B in persistent Salmonella Typhimurium infections in pigs. Vet Microbiol 128:364–373

Di Pasqua R, Mauriello G, Mamone G, Ercolini D (2013) Expression of DnaK, HtpG, GroEL and Tf chaperones and the corresponding encoding genes during growth of Salmonella Thompson in presence of thymol alone or in combination with salt and cold stress. Food Res Inter 52:153–159

Van Parys A, Boyen F, Verbrugghe E, Volf J, Leyman B, Rychlick I, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F (2010) Salmonella Typhimurium resides largely as an extracellular pathogen in porcine tonsils, independently of biofilm-associated genes csgA, csgD and adrA. Vet Microbiol 144:93–99

Boyen F, Pasmans F, Van Immerseel F, Morgan E, Adriaensen C, Hernalsteens JP, Decostere A, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F (2006) Salmonella Typhimurium SPI-1 genes promote intestinal but not tonsillar colonization in pigs. Microbes Infect 8:2899–2907

Authors’ contributions

EV, AVP and BL performed the animal experiments. EV and AVP designed the mutants. EV and AVP performed the in vitro tests. EV, AVP, FB, FH and FP conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination. EV, FH and FP co-drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of Nathalie Van Rysselberghe and Anja Van den Bussche is greatly appreciated. This work was supported by the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT Vlaanderen), Brussels, Belgium (Grant IWT Landbouw 040791).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Elin Verbrugghe and Alexander Van Parys shared first author

Freddy Haesebrouck and Frank Pasmans shared senior authorship

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Verbrugghe, E., Van Parys, A., Leyman, B. et al. HtpG contributes to Salmonella Typhimurium intestinal persistence in pigs. Vet Res 46, 118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-015-0261-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-015-0261-5