Abstract

Background

Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent psychiatric diseases in the peripartum period. They can lead to relevant health consequences for mother and child as well as increased health care resource utilization (HCRU) and related costs. Due to the promising results of mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) and digital health applications in mental health, an electronic MBI on maternal mental health during pregnancy was implemented and assessed in terms of transferability to standard care in Germany. The present study focused the health economic outcomes of the randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Methods

The analysis, adopting a payer’s and a societal perspective, included women of increased emotional distress at < 29 weeks of gestation. We applied inferential statistics (α = 0.05 significance level) to compare the intervention group (IG) and control group (CG) in terms of HCRU and costs. The analysis was primarily based on statutory health insurance claims data which covered the individual observational period of 40 weeks.

Results

Overall, 258 women (IG: 117, CG: 141) were included in the health economic analysis. The results on total health care costs from a payer’s perspective indicated higher costs for the IGi compared to the CG (Exp(ß) = 1.096, 95% CI: 1.006–1.194, p = 0.037). However, the estimation was not significant after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.006). Even the analysis from a societal perspective as well as sensitivity analyses did not show significant results.

Conclusions

In the present study, the eMBI did neither reduced nor significantly increased health care costs. Further research is needed to generate robust evidence on eMBIs for women suffering from peripartum depression and anxiety.

Trial registration

German Clinical Trials Register: DRKS00017210. Registered on 13 January 2020. Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent psychiatric diseases in the perinatal period [1, 2]. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews show prevalence rates of 12% and 15% for perinatal depression and anxiety, respectively [1, 3]. In Germany, depressive disorders were observed in approximately 9% and anxiety in 17% of pregnant women [4]. Mental health problems during pregnancy were found to be associated with e.g. postpartum depression, increased cortisol levels, caesarean section, prematurity, low birth weight, poor mother-child-interaction and physiological and impaired (socio-)emotional development in childhood [5,6,7,8,9,10] as well as increased health care resource utilization (HCRU) and related costs [11, 12]. Bauer et al. [12] account for total lifetime costs of peripartum depression and anxiety amounting to 92,537€ (£75,728 ) and 42,538€ (£34,811) [13] per woman, respectively. These far-reaching consequences for mothers, children, health care systems, and societies highlight the public health relevance of peripartum anxiety and depression.

Due to their efficacy, low costs and low-threshold accessibility, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have become increasingly popular in mental health care [14, 15] and represent a promising approach for women suffering from anxiety and depression during the peripartum period [16,17,18,19]. In recent years, digital health has been increasingly prioritized in the German health care system, not least through the promotion of digital health applications [20]. Evidence demonstrates that online-based interventions potentially reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression [21] and appear to be cost-effective [22]. Furthermore, studies indicate that online-based interventions could be a cost-effective way to improve perinatal mental health [23, 24]. However, robust results with a focus on the peripartum period are still lacking.

To address this gap in research, an electronic MBI (eMBI) on maternal mental health during pregnancy was implemented and assessed in terms of transferability to standard care in the German statutory health insurance (SHI). A multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and the costs of the intervention [25]. Results of the main (effectiveness) evaluation show that the intervention is beneficial, e.g. significantly reduced the risk of postpartum depression [26]. The current study focused on the health economic analysis of the new health care approach and aimed to compare the intervention group (IG) and control group (CG) in terms of total health care costs. Moreover, according to the fact that a high proportion of depression treatments is allocated to general practitioners (GPs) [27], we performed detailed analysis on outpatient HCRU.

Methods

Study design

An RCT was performed examining the effectiveness and costs of an eMBI to promote maternal mental health during pregnancy, which was initiated by University women’s hospital of Heidelberg (Germany), implemented in 2018 in cooperation with the Department for Women’s Health at University of Tuebingen and evaluated at Ludwig Maximilian UniversityMunich and Bielefeld University. A full description of the methodology of the RCT can be found elsewhere [25]. In this analysis, we focused on health economic outcomes and compared the IG and the CG in terms of HCRU and costs. The observation period covered 40 weeks, beginning in the last trimester (28th week) of pregnancy. According to methodological guidelines [28], the main analysis adopted a payer’s (SHI) perspective, which was extended to a societal perspective.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of eight weekly (45-min.) sessions [29, 30] and combined psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness exercises. The eMBI taught women how to deal with stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms and supported the autonomy of the expectant mother. The digital application included e.g. videos, audio files and interactive worksheets [25].

Study population

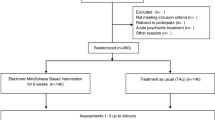

Study participants were recruited between March 2019 and September 2020 via routine care in the study centers (University Hospitals Heidelberg and Tübingen) and in gynecological practices, where the women were screened routinely for emotional distress. They were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: increased level of emotional distress (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [31, 32] score > 9), age ≥ 18, gestation < 29 weeks, sufficient German language skills, internet access, insured with one of the participating SHI companies. Exclusion criteria were multifetal pregnancy, acute psychotic episodes or psychiatric diagnoses (schizophrenic disorders, suicidality, substance abuse disorders, borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorders, traumatic experiences without reference to the current pregnancy) or the need for an acute psychiatric treatment and participation in a MBI during the current pregnancy. Study participants were randomly assigned at a ratio of 1:1 to the IG (eMBI) or CG (treatment as usual). The group variable was blinded with a binary code and was only known to the study staff and the app developers [25]. Since the claims data were only available for the follow-up period until June 2021, participants with incomplete observation periods were excluded. Thus, the health economic analysis included a subsample of the study population included in the evaluation of the effectiveness (Fig. 1).

Data collection and outcome measures

The analysis was mainly based on claims data provided by involved SHI companies (Techniker Krankenkasse, AOK Baden-Württemberg, mhplus, GWQ ServicePlus AG). Additionally, self-reported baseline characteristics (e.g. educational level, net household income, number of children at home, level of stress (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [33, 34]), symptoms of depression (EPDS [31, 32]), pre-existing physical and psychiatric diseases, study center) were included (Additional File1, Table 1). To ensure privacy and data protection, data were pseudonymized and did not allow for re-identification of the individuals. The analysis focused on direct health care costs which include inpatient and outpatient services, pharmaceuticals, therapeutic devices, non-physician specialist services (e.g. physical therapy), university/psychiatric outpatient department services and outpatient surgeries, midwifery services and intervention costs. Besides monetary units, measures of HCRU, such as physician consultations, hospital length of stay (LOS) and daily defined doses (DDD), were reported. The latter were determined by adding data provided by the AOK Research Institute (WIdO) [35, 36]. To broaden the analysis to a societal perspective, productivity losses were added. We followed the friction cost approach, applying a vacancy period of 99 days [37], to avoid overestimations of productivity losses [38]. Indirect costs resulted from the individual’s days of disability documented in SHI claims data multiplied by average values of per day salary (\(\:\frac{\text{a}\text{n}\text{n}\text{u}\text{a}\text{l}\:\text{s}\text{a}\text{l}\text{a}\text{r}\text{y}\:\text{i}\text{n}\:\text{G}\text{e}\text{r}\text{m}\text{a}\text{n}\text{y}}{\text{n}\text{u}\text{m}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{e}\text{m}\text{p}\text{l}\text{o}\text{y}\text{e}\text{e}\text{s}}\text{*}365\:\text{d}\text{a}\text{y}\text{s}\)) of the general population [38,39,40].

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study population and outcome variables were examined by descriptive and inferential statistics (e.g. t-tests, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, chi-square tests). Additionally, Little’s test was conducted to test the assumption of missing completely at random [41]. To analyse the intervention effect on outpatient services and total health care costs, we used generalized additive models [42]. Different model specifications have been investigated to achieve an acceptable model fit. While an inverse gamma distribution addressed the skewness of cost data, a negative binomial distribution fitted the count data (physician consultations). Variable selection strategies were applied to identify potentially relevant independent variables from the data set. Thus, initial model formulas included study group, study center, educational level, number of children at home, stress level (PHQ), symptoms of depression (EPDS) and pre-existing physical and psychiatric diseases as well as interaction terms. The final model formula resulted from backward selection based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [43]. Following the practical advices on variable selection using AIC defined by Sutherland et al. (2023) [44], 85% as well as 95% confidence Inervals (CI) were calculated. Both, initial and final formulas can be found in Additional File 1 (Table 2). In addition, Bonferroni correction was used to consider multiple testing and was reported for relevant estimations of the regression analyses. Model fit and reliability of the results were examined by diagnostic plots (e.g. residual plot). Sensitivity analyses of total health care costs (SHI-perspective) considered 30% higher and lower intervention costs, as well as an extended sample to address exclusions due to limited data availability. The latter included participants with only slightly shorter (four weeks) observation periods. Statistical analyses were performed using the open-source software R (version 4.2.1) [45] (e.g. Package GAMLSS [42]) and were based on a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

As the underlying data differed from the evaluation of the effectiveness, the health economic analysis involved a reduced sample of 258 women (IG: 117,CG: 141) (Fig. 1). The onset of COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 lead to decreasing HCRU in Germany [46, 47]. Thus, we examined the overlapping time span of the pandemic and women’s individual observation period, but found no significant between group differences (p-value = 0.877).

The average age of women participating in the study was 32 years and their household income was usually above 1500€ (Table 1). The proportion of women with children at home was non-significantly higher in the IG compared to the CG. A statistically significant difference occurred in the level of education (p = 0.005). Further, IG participants (6.30, SD = 2.81) showed significantly lower baseline stress level (PHQ) compared to the CG (7.26, SD = 3.77) (t = 2.269, p = 0.024). Little’s test [41] confirmed the assumption of missing completely at random (X²=35.77, p = 0.573).

The main analysis from a health economic perspective focused on total HCRU and costs. Table 2 shows the mean values and standard deviations of women’s resource use within the study period, adopting a SHI-perspective. Most cost-intensive were inpatient services, which were mainly related to childbirth. On average, these costs arose to the amount of 3363.67€ (SD = 1643.36€) in IG and 3509.82€ (SD = 2692.00€) in CG. Further relevant components in terms of costs were outpatient (IG: 1475.06€, SD = 1077.06€; CG: 1491.34€, SD = 1065.37€) and midwifery services (IG: 1156.71€, SD = 834.98€; CG: 1196.95€, SD = 1040.53€). Non-physician services and therapeutic devices generated rather low costs. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests did not show statistically significant between group differences in utilization or (total) costs of health care services.

The generalized additive model (inverse gamma distribution) on total health care costs from a SHI-perspective (Table 3) indicated higher costs for women in the IG compared to the CG (Exp(ß) = 1.096, 95%-CI: 1.006–1.194, p = 0.037). However, the estimate was not significant after Bonferroni correction (new significance level p < 0.006). Besides the study group, the final regression term included the number of children at home, initial stress level and pre-existing psychiatric and physical diseases. Considering the 85% CI does not lead to opposing interpretations of the model (Additional File 1, Table 3). According to model diagnostics, the model fit showed deviations, particularly at lower and upper margins. Residual and QQ-plots did not show further inaccuracies (Additional File 1, Figs. 1–2). Sensitivity analyses, considering 30% higher and lower intervention costs and an extended study population, differed only slightly from the main results and did not show a significant intervention effect after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.006) (Additional File 1, Tables 5 and 6).

Productivity losses were measured by women’s days of disability and the mean value of salary of the general population. The durations of disability did not significantly differ between IG (1.37, SD = 4.47) and CG (1.38, SD = 6.07) (p = 0.211). They did not lead to differences in productivity losses (IG: 169.40€, SD = 553.92€; CG: 170.55€, SD = 751.67€; p = 0.213) or total health care costs from a societal perspective, which were 6732.89€ (SD = 2646.74€) in the IG and 6862.76€ (SD = 3801.57€) in the CG (p = 0.082). Along with the analysis adopting a SHI-perspective, we found no statistically significant intervention effect (Exp(ß) = 1.102, 95% CI: 1.008–1.204, p = 0.033) after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.006) on total health care costs from a societal perspective (Table 4). The model diagnostics did not show recognizable differences from the main analysis (Additional File 1, Figs. 3 and 4).

Besides total HCRU, details on outpatient service utilization were analysed. Women included in the study utilized at least one outpatient service within the observed period. On average the IG had 30.74 and CG participants had 31.30 consultations (Table 5), leading to costs of 1475.06€ and 1491.34€, respectively. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests did not reveal significant differences between IG and CG in terms of consultations (p = 0.831) and outpatient costs (p = 0.978). Even the differentiated analyses did not show any significant between group differences in terms of GP and specialist consultations or costs. Whereas women who participated in the intervention had on average 5.71, CG participants had 5.18 GP consultations. As expected, gynaecological and obstetric services represented the most relevant specialist care in terms of utilization and costs (IG: 13.22, 728.58€; CG: 13.28, 718.52€). The number of specialist consultations in neurology, psychiatry or psychotherapy was non-significantly lower in IG (3.01) compared to CG (3.48). These services caused the highest average cost per case in outpatient care.

Multivariate analyses were performed on the number of overall physicians as well as GP consultations. The results of the generalized additive model (negative binomial distribution) on the total number of physician consultations can be found in Additional File 1 (Table 7). The estimations did not reveal a statistically significant reduction in outpatient HCRU due to the intervention. In contrast, IG participants with a pre-existing psychiatric disease showed an increased number of consultations (Exp(ß) = 1.407, 95% CI: 1.116–1.775, p = 0.004), which was significant after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.006). Due to this interaction, the interpretation of the study group effect required the consideration of a pre-existing psychiatric disease (Yes/No). In terms of GP consultations (Additional File 1, Table 8), we found no statistically significant intervention effect (Exp(ß) = 1.224, 95% CI: 0.947–1.584, p = 0.124). However, diagnostic plots for both regression models on outpatient service utilization accounted for limited quality of the estimations. Thus, the fitted values did not adequately cover the observed values and the results are of limited validity (Additional File, Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Discussion

In this study we aimed to evaluate the impact of an eMBI for expectant mothers on HRCU and total costs, adopting a SHI-perspective, extended to a societal perspective. The intervention was not found to cause reductions in total health care costs of women in the third trimester of pregnancy until five months after birth. Analyses of total health care costs adopting a SHI and societal perspective showed non-significantly higher costs for the IG compared to the CG. The sensitivity analyses did not lead to divergent results and interpretations. Moreover, the analyses of outpatient services did not result in conclusions regarding an interventional effect and accounted for limited model quality. The diagnostic plots for the main models were acceptable but showed deviations, particularly at lower and upper margins.

The relevance of digital health applications has considerably increased in recent years. Online interventions are potentially cost-effective alternatives in the treatment of depression and anxiety. However, the conditions and cost components of evaluation studies vary widely [48,49,50]. The health economic perspective has rarely been considered in previous evaluations of digital interventions for peripartum depression or anxiety disorders [51]. The cost-effectiveness of non-digital approaches has been the subject of numerous studies, but even in this field, the heterogeneity of designs and settings leads to uncertainties [52]. Monteiro et al. (2022) examined a web-based self-directed cognitive behavioural therapy to promote mental health in mothers at low risk for postpartum depression using waitlist comparison. According to the results, the approach leads to non-significant cost savings and a non-significant increase in Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). The authors conclude that from a societal perspective, implementing the intervention could be a cost-effective approach to improve peripartum mental health [23]. Zheng et al. (2022) compare two psychoeducational interventions (web-based/home-based) with a control group in their three-arm RCT. The study focuses on first-time mothers in the early postpartum period and states that the web-based intervention dominates both alternatives and has the highest probability of cost-effectiveness. However, the researchers point out uncertainties of the analyses. Thus, the present study is consistent with the state of research in terms of non-significant results and existing uncertainties [24].

When interpreting our results, the following strengths and weaknesses should be considered. Compared to the general female population in Germany [53], the study participants represent a quite highly educated sample, with a proportion of about 68% having a university or university of applied sciences entrance qualification. Previous studies showed associations between individual socioeconomic factors and the level of HCRU. As the effect depends on the health care sector [54], the impact on external validity cannot be conclusively assessed. With regard to the percentage of study participants with no children at home (probably primiparous, about 56%), the sample is approximately comparable to the target group in terms of age [55]. Considerable effort was made to generate robust results from the analysis. The study design (RCT) is considered the gold standard in scientific research and prevents several potential biases [56]. In addition, possible confounders and uncertainties were addressed by multivariate analyses and sensitivity analyses. Along with usual standards in RCTs, the sample size calculation of the current study was based on the primary (effectiveness) outcome. It should be noted, that the health economic evaluation could have required a larger sample size to detect significant effects [57]. Although the randomization intends to ensure structural balance of the study groups, it cannot be ruled out that the results might have been affected by latent unmeasured variables (e.g. individual coping mechanisms). Further limitations refer to the process of model selection by AIC which is characterized by its practicability but entails a potential bias due to multiple testing. Thus, inflated significance was addressed by Bonferroni correction. Additionally, along with suggestions on model reporting using AIC [44], 95% and 85% CIs were calculated to provide intervals consistent with the selection strategy.

The analysis was mainly based on SHI claims data, which provide comprehensive and objective information on participants’ HCRU and related costs. However, it should be noted that the data are not primarily collected for research purposes [58, 59]. The heterogeneity of claims data provided by different SHIs requires intensive data preparation [60]. To examine the plausibility of SHI data, reports available from e.g. the Federal Association of SHI Physicians [61] and WIdO [62] were used for comparison and did not refer to implausibility. In general, it can be assumed, that the usage of German SHI claims data will be improved by the Health Data Lab (HDL)[63]. In terms of productivity losses, potential overestimations need to be considered. The calculation was based on national average values. Due to non-gender specific national average values, the comparatively low employment and salary level of women is not represented in the data [64]. In general, indirect costs caused by incapacity for work account for a large proportion of total costs of mental illness [65]. Within the present population this cost component is less relevant (approximately 2.5% of total health care costs from a societal perspective), because of the relatively short observational period of 40 weeks including maternity leave and in many cases parental leave which contradict the status of incapacity for work [66]. In addition, mindfulness interventions during pregnancy might have far-reaching benefits [67]. Due to a restricted study period, potential long-term effects on HCRU and costs could not be examined. Some recommendations for future research can be derived from the limitations. For more valid results, health economic outcomes should be included in power calculations. Another methodological improvement refers to alternative model selection strategies, such as cross-validation. Moreover, studies should be based on comprehensive data sets. These should include potential confounders as well as HCRU and cost data covering extended observation periods. Also, for this purpose, the results generated from the current study could inform predictive health economic modelling approaches.

Conclusion

In the present study, the eMBI was not found to reduce nor significantly increase health care costs. Overall, these findings are in line with the current state of research, yielding non-significant results. Further research is needed to strengthen the evidence on interventions to promote perinatal mental health in general as well as eMBIs for women suffering from peripartum depression and anxiety. Ideally, the studies should involve women’s long-term impairments and costs as well as the wide-ranging and intergenerational economic consequences.

Data availability

The datasets analysed for the current study are not publicly available due to project specific agreements of data protection. On reasonable request, possibilities of data access for external researchers have to be proved. Requests can be made to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

akaike information criterion

- CEA:

-

cost-effectiveness

- CG:

-

control group

- CUA:

-

cost-utility analysis

- DDD:

-

Defined Daily Dose

- eMBI:

-

electronic mindfulness-based intervention

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- GP:

-

general practitioners

- HRQoL:

-

health-related quality of life

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- IG:

-

intervention group

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SHI:

-

Statutory health insurance

- WIdO:

-

AOK Research Institute

- QALY:

-

Quality-Adjusted Life Years

References

Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003.

Babb JA, Deligiannidis KM, Murgatroyd CA, et al. Peripartum depression and anxiety as an integrative cross domain target for psychiatric preventative measures. Behav Brain Res. 2015;276:32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.03.039.

Dennis C-L, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315–23. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179.

Wallwiener S, Goetz M, Lanfer A, et al. Epidemiology of mental disorders during pregnancy and link to birth outcome: a large-scale retrospective observational database study including 38,000 pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(3):755–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05075-2.

Field T. Prenatal depression effects on early development: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.09.008.

Field T. Prenatal anxiety effects: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2017;49:120–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.08.008.

Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, et al. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050701209560.

Madigan S, Oatley H, Racine N, et al. A Meta-analysis of maternal prenatal depression and anxiety on child Socioemotional Development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(9):645–e6578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.012.

Goodman JH, Guarino A, Chenausky K, et al. CALM pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(5):373–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0402-7.

Reck C, Noe D, Gerstenlauer J, et al. Effects of postpartum anxiety disorders and depression on maternal self-confidence. Infant Behav Dev. 2012;35(2):264–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.12.005.

Larsson C, Sydsjö G, Josefsson A. Health, sociodemographic data, and pregnancy outcome in women with antepartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):459–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000136087.46864.e4.

Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005.

OANDA Währungsrechner. https://www.oanda.com/currency-converter/de/?from=GBP&to=EUR&amount=34811. Accessed 31 Jan 2023.

Klainin-Yobas P, Cho MAA, Creedy D. Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on depressive symptoms among people with mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):109–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.014.

Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011.

Dunn C, Hanieh E, Roberts R, et al. Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on women’s psychological distress and well-being in the perinatal period. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(2):139–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0264-4.

Byrne J, Hauck Y, Fisher C, et al. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based Childbirth Education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59(2):192–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12075.

Dhillon A, Sparkes E, Duarte RV. Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(6):1421–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0726-x.

Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT, et al. Benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1319-3.

Sauermann S, Herzberg J, Burkert S, et al. DiGA - A chance for the German Healthcare System. J Eur CME. 2022;11(1):2014047. https://doi.org/10.1080/21614083.2021.2014047.

Spijkerman MPJ, Pots WTM, Bohlmeijer ET. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: a review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:102–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009.

Rohrbach PJ, Dingemans AE, Evers C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of internet interventions compared with treatment as Usual for people with Mental disorders: systematic review and Meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e38204. https://doi.org/10.2196/38204.

Monteiro F, Antunes P, Pereira M, et al. Cost-utility of a web-based intervention to promote maternal mental health among postpartum women presenting low risk for postpartum depression. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1):e62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462322000447.

Zheng Q, Shi L, Zhu L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of web-based and home-based postnatal psychoeducational interventions for first-time mothers: economic evaluation alongside Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e25821. https://doi.org/10.2196/25821.

Müller M, Matthies LM, Goetz M, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an electronic mindfulness-based intervention (eMBI) on maternal mental health during pregnancy: the mindmom study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):933. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04873-3.

Hassdenteufel K, Müller M, Abele H, et al. Using an electronic mindfulness-based intervention (eMBI) to improve maternal mental health during pregnancy: results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2023;330:115599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115599.

Gaebel W, Kowitz S, Fritze J, et al. Use of health care services by people with mental illness: secondary data from three statutory health insurers and the German Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(47):799–808. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2013.0799.

Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen. (2020) Allgemeine Methoden - Version 6.0 2020.

Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, et al. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: a pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(2):134–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000068.

Ringwald J, Gerstner L, Junne F, et al. Mindfulness and skills based distress reduction in Oncology: Das Webbasierte Psychoonkologische make it training (mindfulness and skills based distress reduction in Oncology. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2019;69(9–10):407–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0835-6905. The Web-Based Psycho-Oncological Make It Training.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Bergant AM, Nguyen T, Heim K, et al. Deutschsprachige Fassung und Validierung Der Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (German language version and validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale). Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123(3):35–40. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1023895.

(2004) Screening psychischer Störungen Mit dem Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D).

Löwe B, Spitzer R, Zipfel S, et al. Prime MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). Komplettversion und Kurzform; 2002.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. (2021) Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2021.

Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK. (2022) Arzneimittel-Stammdatei des GKV Arzneimittelindex.

(2018) WISTA. Wirtschaft Und Statistik, 3rd edn. Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden.

Greiner W, Damm O. 3 die Berechnung Von Kosten und Nutzen. In: Schöffski O, von der Graf J-M, editors. Gesundheitsökonomische Evaluationen. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. pp. 23–42.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022) Erwerbstätigkeit. Erwerbstätige und Arbeitnehmer nach Wirtschaftsbereichen (Inlandskonzept) 1000 Personen. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Arbeit/Arbeitsmarkt/Erwerbstaetigkeit/Tabellen/arbeitnehmer-wirtschaftsbereiche.html.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022) Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen. Bruttonationaleinkommen, verfügbares Einkommen und Volkseinkommen. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Volkswirtschaftliche-Gesamtrechnungen-Inlandsprodukt/Tabellen/lrvgr04.html#242556.

Little RJA. A test of missing completely at Random for Multivariate Data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Rigby RA, Stasinopoulos DM. Generalized additive models for location, scale and shape (with discussion). J Royal Stat Soc C. 2005;54(3):507–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9876.2005.00510.x.

Fahrmeir L, Kneib T, Lang S, et al. Regression. Models, methods and applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013.

Sutherland C, Hare D, Johnson PJ, et al. Practical advice on variable selection and reporting using Akaike information criterion. Proc Biol Sci. 2023;290(2007):20231261. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.1261.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Wien, Österreich: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020.

Heidemann C, Reitzle L, Schmidt C, et al. Nichtinanspruchnahme Gesundheitlicher Versorgungsleistungen während Der COVID-19-Pamdemie: Ergebnisse Der CoMoLo-Studie. Robert Koch-Institut; 2022.

Mostert C, Drogan D, Klauber J, et al. WIdO-Report: Entwicklung Der Krankenhausfallzahlen während Des Coronavirus-Lockdowns. Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK; 2020.

Donker T, Blankers M, Hedman E, et al. Economic evaluations of internet interventions for mental health: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3357–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001427.

Manoharan A, McMartin K, Young C, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for major depression and anxiety disorders: a Health Technology Assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2019;19(6):1–199.

Mitchell LM, Joshi U, Patel V, et al. Economic evaluations of internet-based psychological interventions for anxiety disorders and Depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;284:157–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.092.

Hussain-Shamsy N, Shah A, Vigod SN, et al. Mobile Health for Perinatal Depression and anxiety: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e17011. https://doi.org/10.2196/17011.

Camacho EM, Shields GE. Cost-effectiveness of interventions for perinatal anxiety and/or depression: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e022022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022022.

Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung. (2021) Allgemeiner Schulabschluss. Schulabschluss der Bevölkerung nach Alter und Geschlecht, 2020. https://www.demografie-portal.de/DE/Fakten/schulabschluss.html;jsessionid=D43E5A4C6A49980CCBB947210466FBD7.internet281?nn=677102.

Klein J, Hofreuter-Gätgens K, Knesebeck O, von dem. Socioeconomic status and the Utilization of Health Services in Germany: a systematic review. In: Janssen C, Swart E, von Lengerke T, editors. Health Care utilization in Germany. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2014. pp. 117–43.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022) Durchschnittliches Alter der Mutter bei der Geburt des Kindes 2021 (biologische Geburtenfolge) nach Bundesländern. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Geburten/Tabellen/geburten-mutter-alter-bundeslaender.html.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Med Working Group JAMA. 1995;274(22):1800–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.274.22.1800.

Petrou S, Cooper P, Murray L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a preventive counseling and support package for postnatal depression. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(4):443–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462306051361.

Zeidler J, Braun S. Sekundärdatenanalysen. In: Schöffski O, von der Graf J-M, editors. Gesundheitsökonomische Evaluationen. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012.

Kreis K, Neubauer S, Klora M, et al. Status and perspectives of claims data analyses in Germany-A systematic review. Health Policy. 2016;120(2):213–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.01.007.

Winkler H, Koehler F, Reinhold T, et al. Nutzung Von Routinedaten unterschiedlicher gesetzlicher Krankenkassen: Ein Erfahrungsbericht Aus Der TIM-HF2-Studie Zur Datenerschließung, -validierung und -aufbereitung (utilization of routine data from different statutory health insurance funds: a practical report of experience from the TIM-HF2 study about data acquisition, validation, and processing). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2023;66(9):1000–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-023-03735-y.

Kassenärztlichen B. (2019) Honorarbericht. Quartal 4/2019.

Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK. Der GKV-Arzneimittelmarkt. Klassifikation, Methodik Und Ergebnisse 2021. Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK; 2021.

Ludwig M, Schneider K, Heß S, et al. Aufbau Des Neuen „Forschungsdatenzentrums Gesundheit Zur Datenbereitstellung für die Wissenschaft (establishment of the new Health Data Lab to provide data for science). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2024;67(2):131–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-023-03831-z.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2021) Arbeitsmarkt und Verdienste. Auszug aus dem Datenreport 2021. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Service/Statistik-Campus/Datenreport/Downloads/datenreport-2021-kap-5.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

König H-H, Friemel S. Gesundheitsökonomie Psychischer Krankheiten (Health economics of psychological diseases). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2006;49(1):46–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-005-1195-2.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022) Öffentliche Sozialleistungen. Statistik zum Elterngeld - Leistungsbezüge. file:///C:/Users/lhasemann/Downloads/elterngeld-leistungsbezuege-j-5229210217004.pdf.

Roubinov DS, Epel ES, Coccia M, et al. Long-term effects of a prenatal mindfulness intervention on depressive symptoms in a diverse sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022;90(12):942–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000776.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Techniker Krankenkasse, AOK Baden-Württemberg, mhplus and GWQ ServicePlus AG for the provision of claims data. We also thank John Andrew Grosser (Bielefeld University) for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by innovation funds of the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) (No.: 01NVF17034).

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM, SW, AB and WG contributed to the study conception and design and provided comments/revisions to the manuscript. Supported by SE, LH performed the present analyses and drafted the manuscript. LH, SE, MM, SW, AB and WG read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Heidelberg University (S-744/2018) and follows the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasemann, L., Elkenkamp, S., Müller, M. et al. Health economic evaluation of an electronic mindfulness-based intervention (eMBI) to improve maternal mental health during pregnancy – a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Health Econ Rev 14, 60 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-024-00537-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-024-00537-z