Abstract

Background

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are not only a safety and quality of care issue for patients, but also an economic issue with significant costs. Because they often occur during hospital stays, it is necessary to accurately quantify the costs of ADEs. This review aimed to investigate the methods to calculate these costs, and to characterize their nature.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify methods used to assess the cost of ADEs on Medline, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Original articles published from 2017 to 2022 in English and French were included. Economic evaluations were included if they concerned inpatients.

Results

From 127 studies screened, 20 studies were analyzed. There was a high heterogeneity in nature of costs, methods used, values obtained, and time horizon chosen. A small number of studies considered non-medical (10%), indirect (20%) and opportunity costs (5%). Ten different methods for assessing the cost of ADEs have been reported and nine studies did not explain how they obtained their values.

Conclusions

There is no consensus in the literature on how to assess the costs of ADEs, due to the heterogeneity of contexts and the choice of different economic perspectives. Our study adds a well-deserved overview of the existing literature that can be a solid lead for future studies and method implementation.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration CRD42023413071.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drugs have become indispensable therapeutic tools and are a key factor in improving the quality of life and life expectancy of many people, but their use (i.e. prescribing, dispensing, preparation and administration) remains complex and a potential source of adverse events. As stated in another study, the life expectancy itself also has an important impact on a country’s economy [1]. The identification, characterization and understanding of these adverse events has been continuously improving since the late 90s [2]. The World Health Organization defines an Adverse Drug Event (ADE) as an unfavorable consequence involving a drug, whether preventable (e.g., the result of a Medication Error (ME)) or not (e.g., an Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR)) [3]. Unsafe medication practices and MEs are a leading cause of injury and avoidable harm in health care systems across the world. Most of ADEs do not result in significant harm for patients, but some drugs can lead to prolonged hospital stays, complications and disabling sequelae or death. All this inexorably leads to an increase in the cost of therapy, surplus that could be used to fund other health needs. Numerous national surveys around the world have described and quantified ADEs as a public health issue. However, only a few studies have focused on methods for evaluating the costs generated by ADEs, even though the WHO estimated in 2017 that the annual cost generated by MEs was 42 billion dollars worldwide. This represents nearly 1% of all health care expenditure worldwide [4]. ADEs represent an important item of expenditure for healthcare systems and their prevention could be associated with significant cost savings. There is no consensus on how to evaluate the costs of ADEs. In similar clinical settings, there is no evidence to suggest that one approach should be used over another, and this is where the difficulty lies in establishing a precise method for assessing the real cost of ADEs to compare different outcomes.

Our systematic review aims to assess the different methods used for evaluating the economic impact of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients, in order to implement a better management system for stakeholders.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify recent studies that assessed the cost of ADEs. The methodological data of this systematic review is in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement recommendations updated in 2020 [5]. The protocol of this systematic review is registered in Prospero under the ID: CRD42023413071.

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted on three databases Medline (Pubmed), Web of Science and Google Scholar to identify studies presenting the nature, value and methods of assessing the costs of ADEs. The searches included studies published between 1st January 2017 and 1st June 2022. Search algorithms are as follows:

-

Medline: (((pharmacoeconomic*[Title]) OR (economic*[Title]) OR (cost*[Title])) AND ((adverse drug event*[Title]) OR (adverse drug reaction*[Title]) OR (medication error*[Title])))

-

Web of science: (((TI = ((pharmacoeconomic* OR economic* OR cost*) AND (adverse drug event* OR adverse drug reaction* OR medication error*)))))

-

Google Scholar: allintitle: pharmacoeconomic OR economic OR costs AND “adverse drug events” OR “adverse drug reaction” OR “medication error”

The search associated cost-related keywords with the different types of ADEs.

Study selection and exclusion criteria

Initially, two researchers (MD and GLB) screened by hand the title and abstracts. Systematic reviews and publications not presented as original articles (letters, congress abstracts, thesis) were excluded. Only literature published in English and French was included. Titles and abstracts were read to exclude off-topic publications that did not address costing and ADEs (in its broadest definition, including ADRs and MEs) and which did not include inpatients. The articles for which the full text was unavailable were also excluded. The publications were not selected according to the type of study, their geographical origin, or the socio-demographic or clinical characteristics of the patients included, given the limited number of articles published on this subject. Then, after sourcing the articles, the full texts were read and analyzed independently by two researchers (MD and GLB) to identify each methodology used to evaluate the costs associated with ADEs.

Data extraction

The general data was extracted from the articles included in the review to characterize the studies. Firstly, the clinical characteristics were retrieved: general data (authors, publishing year), geographical data (country, clinical area), method and study design, time horizon, population settings, suspected drugs and type of ADEs. Then, the economic settings as the type of cost analysis, cost components assessed and results. Two authors (MD and GLB) have assembled a table to aggregate the extracted data. This dataset has been adapted throughout the work to clarify the information comprised in the publications. Table 1 presents the terminology used to define, classify and harmonize the different components of a cost (direct, indirect or opportunity) [6].

Qualitative appraisal

Authors used the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist, version 2022 [7]. Quality was independently assessed by two authors (MD and GLB). A score was attributed to each article. When the information was available and well reported, a score of 1 point was assigned. If the information was incomplete, 0.5 point was assigned. Finally, 0 point was assigned when the information was not present. The final scores were converted into a mark ranging from 0 to 1. A high mark corresponded to a higher reporting quality. All discrepancies in the assessment were resolved by consensus between two authors (MD and GLB). The discount rate was considered relevant only for time horizons above 1 year.

Data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). All costs were converted into Euro (€) according to the closing exchange rate from 07/09/2022 and were not adjusted for inflation or discounted.

Ethical aspects

This is a secondary literature review; no ethics committee approval was required.

Results

Search results

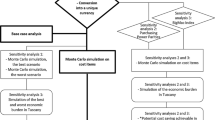

The initial search identified a total of 127 potentially relevant publications. After duplicates removal and after applying the exclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts, only 26 publications remained. The full text reading resulted in a final selection of 20 articles used for the review. The selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the studies

A methodology summary of the included studies is presented in Table 2. Seven publications were from USA, two from Japan, South Africa, and Sweden, respectively and one from Canada, France, India, Iran, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, respectively. None of the studies were published in 2020. Fifteen studies focused only on secondary and tertiary care (inpatients), while five focused on primary, secondary, and tertiary care (both inpatients and outpatients). All the publications included were observational studies, 90% were retrospective and 60% were multi-centric. Three studies were based on pharmacovigilance databases (15%) [8,9,10]. More than half of the studies included all ADEs (n = 11, 55%), while eight focused on ADRs and only one on MEs. Twelve studies (60%) were not focused on a specific therapeutic group. Among the studies which analyzed a specific therapeutic group, the cost of ADEs caused by anti-infective drugs (n = 3, 15%) [11,12,13] or painkiller drugs (n = 2, 10%) [14, 15] were the most evaluated. Most of the studies did not assess a specific ADE (n = 18, 90%). Only one focused on cutaneous ADEs [11] and another on gastrointestinal ADEs [14]. Two studies (10%) evaluated the costs of ADEs in geriatric population [16, 17] and two (10%) in pediatric population [12, 18]. Eight (40%) studies included ≤ 1000 patients and 11 (55%) included > 1000 patients. One study did not specify the number of patients included and expressed its results in number of events [8].

Cost analysis

As illustrated in Table 3, all of the 20 selected studies conducted cost analyses. Half (50%) of them had a time horizon ≤ 1 year, with an average of 30 months and a median of 12.5 [7.5–48.0] months. The inputs and methods used to estimate or calculate costs generated by ADEs had a high degree of heterogeneity. Synthesized in Table 4, 15 studies directly calculated the cost of ADEs while five studies estimated this cost based on external data or previous studies.

Direct costs

Among the studies included, 80% of cost analyses were based only on direct costs and did not assess indirect or opportunity costs. When direct costs were calculated, most studies (n = 10) considered only one direct cost, while one study reported two types of direct costs and nine studies included 3 or more direct costs (Table 3).

Only 2 studies considered non-medical costs. Knight et al. [11] included the cost of food served to the patients in their calculation and Kurle et al. [22] included the cost of patients’ transport to hospital.

Indirect / opportunity costs

Of the 20 selected studies, 4 included indirect costs in their calculations and opportunity costs. Indirect costs were mentioned by Maity et al. [10] including potential lost wages over a lifetime using the human capital approach through the patient perspective and loss of productivity using the friction cost approach through the societal perspective. Kurle et al. [22] only considered the loss of patient’s wages and his/her relatives’ while Natanaelsson et al. [25] consider the loss of productivity and income through patient’s and employer’s perspective. Slight et al. [23] was the only study to consider ADEs generated opportunity costs by estimating the time and cost of responding to clinical decision support alerts (time not used for another activities). No study investigated only indirect costs.

Economic perspectives

Five different perspectives were selected from the 20 publications (Table 3). Eleven studies (55%) were conducted from a hospital perspective, 8 (40%) from a health system and/or public health insurance perspective, 4 (20%) from a patient perspective, 1 (5%) from an employer perspective and 1 (5%) from a societal perspective. Boostani et al. [20] included both a patient and health insurance perspective, Maity et al. [10] included a patient, health system and societal perspective and Natanaelsson et al. [25] a hospital, patient, public health insurance and employer perspective.

Costs results

The main finding regarding the cost of ADEs is the significant heterogeneity of the measures used to report costs and the values obtained. Costs due to ADEs (per hospitalization) ranged from around €6 000 to €10 000 from a hospital, health insurance or health system perspective. Five studies reported incremental costs.

Economic methods

As illustrated in Table 4, 10 different methods for assessing cost of ADEs have been reported. Eleven studies detailed which method they used to calculate their costs. Natanaelsson et al. [25] described two methods, one that underestimated costs and one that overestimated them. Gyllensten et al. [24] described five methods, using different combinations of three calculation steps. Nine studies did not detail how they obtained their values.

Quality appraisal of the included studies

The CHEERS V2022 checklist include 28 points, some were not applicable to all or part of the studies. This quality assessment resulted in a mean score of 0.72, with a median of 0.70 IQR [0.67–0.76] and a minimum score of 0.48 and a maximum of 0.92 (Table 3).

Discussion

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are a significant concern within the healthcare system, rising many challenges to patient safety and healthcare costs.

Through the available information, this is the first study focused on identifying designs, omissions, and potential strategies for assessing the economic consequences associated with ADEs.

The costs of ADEs are of interest to political and social decision-makers as well as to the hospitals themselves.

One of the main findings of our systematic review is the heterogeneity among the methods of reporting costs across different studies and healthcare systems. This can be attributed to differences in healthcare infrastructures, patient populations, and the nature of ADEs.

Most of the studies evaluated direct medical costs (e.g., hospital admission costs) through a hospital perspective. Few studies had a wider perspective (e.g., societal or health system) and explored indirect / opportunity costs. However, in chronic or disabling diseases caused by ADEs, indirect costs may represent the largest share of the cost [30,31,32]. The lack of data needed to value indirect costs and the choice of economic perspective could be reasons for not valuing indirect costs [28]. The patient perspective and non-medical costs were not considered in most of studies whereas the out-of-pocket expenses for the patient or his/her relatives could be high in countries with little public health insurance. So, the health facilities’ or authorities’ perspectives were predominant because studies were conducted to help local or national health decision makers. In their review, Batel Marques et al. [28] noticed that the hospital perspective appears to be the privileged perspective for the identification of ADEs and their costs because of the easy access to a complete description of each case through administrative databases.

The high variation of the costs can be explained by the considerable methodological heterogeneity in the calculation of ADE costs between studies. On the one hand, micro-costing [11, 14, 19, 25] is a cost estimation method that provides accurate values, considering each input consumed, though collecting such detailed usage and valuation data requires significant time and human resources [33]. On the other hand, the ADR vs. non-ADR method [17, 25, 26] is better suited to very large cohorts and allows a more global approach. The matching of patients using propensity scores makes the method very robust for the calculation of incremental costs [34]. Micro-costing is known to underestimate costs due to lack of detail in the registers containing healthcare cost and in the information on lost productivity resulting from ADEs (e.g., sick leave). On the other hand, the ADR vs. non-ADR method may overestimate the costs if there are unmeasured confounding factors. Accordingly, these two methods are complementary.

Therefore, gross costing [10, 13] has several advantages which partly counterbalance the drawbacks of micro-costing. In terms of feasibility, because hospital cost data consists of aggregate data, its estimation can be done quickly. In terms of cost, this method is inexpensive as it largely relies on administrative databases. In this case, the results of the study are easier to generalize. There are several drawbacks as well, especially the lack of precision since a cost cannot be associated with a specific component of the hospital stay because of the aggregate data, which is examined at an overall level. With this method, differences in terms of consumption of resources (e.g. different inpatient profiles) are thus unknown and individual variations are not considered [35].

To investigate indirect costs, the human capital approach uses the amount of gross national product (GNP) per capita. It is straightforward to deduce the average amount of output per individual over a given time. This is a simple method of comparing similar events with each other but does not yield true indirect costs because the method does not consider the exact activity of the patient. Another method is to list as many additional costs associated with the disease as possible, based on the average salary for the patient's socio-professional category or the exact salary if available. This may also allow an assessment of the value of the time lost by the patient’s relatives, for example, in maintaining the patient’s home during his or her absence, for childcare or for travel. The evaluation of indirect costs is interesting because it considers the individual’s social role. Also, Patel et al. [6] similarly concluded for the costs of MEs that there was a general inconsistency of the method used by the researchers. The way similar calculations were performed varied considerably across studies as the nature, number of inputs and stages within a given calculation were not uniform. However, they did not focus on the different costing methodologies, but more on the nature of the costs included. Micro-costing was only specified where it was used.

Because the estimated costs for ADEs are highly affected by the choice of the costing methods, unclear results were obtained when computing the average value of an ADE cost. Hazardous extrapolations of ADE costs are still made using data prior to 2000 [23] and/or very short time horizons [18, 24, 25] and/or a single center or unit of care to make national projections [18], and/or in countries with very heterogeneous GNP and health systems. Assessing the cost of ADEs is therefore a very complex issue and this systematic review confirms that ADEs have a high economic impact. The diversity of drugs, population and methodologies analyzed have been reported too by Batel Marques et al. [28] as a source of high costs variations.

This review confirmed that the methods used for assessing costs were mainly based on the subjective judgement of the researchers. There is a need for a consensual method of calculating costs per perspective to monitor their evolution within a hospital, and also among hospitals or among countries. A standardized method should be established and followed for conducting and reporting cost analyses in order to improve the quality and comparability across studies. One of the proposed solutions is the development and implementation of a decision algorithm that considers the number of patients included, the data available to estimate costs, the time horizon and chosen perspective. A medico-administrative team composed of computer scientists and biostatisticians would allow the processing of data from very large cohorts.

Limitations

Despite the strong insights retrieved from our systematic review, certain limitations are acknowledgeable. Heterogeneity among the included studies may have influenced the results. Moreover, the dynamic nature of healthcare systems and constantly evolving pharmacological environment ask for updates and reevaluations of the economic impact of ADEs. We did not only select original articles with a high quality according to the CHEERS V2022 checklist to assess the global quality of articles on this topic. Only studies published in English and French were included, which excluded several studies published in other languages that focused on local or national issues.

Conclusions and perspectives

Assessing the cost of ADEs is therefore a very complex issue. Standardizing cost assessment methodologies and reporting practices should be a priority in order to optimize the homogeneity of findings and provide more accurate evaluations of the economic burden. Approaching the entanglements of ADE-related costs requires joint efforts from healthcare professionals, policymakers, researchers and even patients.

A universal method for assessing the ADE generated costs could be comprised of both direct and indirect costs evaluation, in order to have an overview on the situation in hand. Although resources consuming, the micro-costing method has the potential of exposing relevant details, even though an association with the ADR vs non-ADR method would be necessary to accurately characterize the cost generating factors.

Additionally, the introduction of modern technologies, such as data analytics and machine learning, highlights the potential for innovation in evaluating ADE generated costs.

Lastly, future studies should consider broader time horizons to efficiently assess the long-term impact of ADEs and, if possible, integrate the socio-economic context and the healthcare system’s specific layout.

Availability of data and materials

Data included in this paper will be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ADE:

-

Adverse drug events

- ME:

-

Medication Error

- ADR:

-

Adverse Drug Reaction

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- CHEERS:

-

Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards

- GNP:

-

Gross National Product

References

Alhassan GN, Adedoyin FF, Bekun FV, Agabo TJ. Does life expectancy, death rate and public health expenditure matter in sustaining economic growth under COVID-19: empirical evidence from Nigeria? J Public Aff. 2021;21(4):e2302.

To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/9728. Cited 2022 Aug 17.

World Health Organization, WHO Patient Safety. Patient safety curriculum guide: multi-professional edition. 2011. p. 272.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO launches global effort to halve medication-related errors in 5 years. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-03-2017-who-launches-global-effort-to-halve-medication-related-errors-in-5-years. Cited 2022 Aug 17.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Patel K, Jay R, Shahzad MW, Green W, Patel R. A systematic review of approaches for calculating the cost of medication errors. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016;23(5):294–301. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000915.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, de Bekker-Grob E, Briggs AH, Carswell C, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Value Health. 2022;25(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1351.

Trumbo H, Kaluza K, Numan S, Goodnough LT. Frequency and associated costs of anaphylaxis- and hypersensitivity-related adverse events for intravenous iron products in the USA: an analysis using the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Drug Saf. 2021;44(1):107–19.

Tissot M, Valnet-Rabier MB, Stalder T, Limat S, Davani S, Nerich V. Epidemiology and economic burden of “serious” adverse drug reactions: Real-world evidence research based on pharmacovigilance data. Therapie. 2022;77(3):291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2021.12.007. Epub 2021 Dec 15.

Maity T, Longo C. Pragmatic pharmacoeconomic analyses by using post-market adverse drug reaction reports: an illustration using infliximab, adalimumab, and the Canada vigilance adverse reaction database. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1231.

Knight LK, Lehloenya RJ, Sinanovic E, Pooran A. Cost of managing severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions to first-line tuberculosis therapy in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24(8):994–1002.

Beck JN, Suppes SL, Smith CR, Lee BR, Leeder JS, VanDoren M, et al. Cost and potential avoidability of antibiotic-associated adverse drug reactions in children. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8(1):66–8.

Schnippel K, Firnhaber C, Berhanu R, Page-Shipp L, Sinanovic E. Direct costs of managing adverse drug reactions during rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis treatment in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(4):393–8.

Pok LSL, Shabaruddin FH, Dahlui M, Sockalingam S, Mohamed Said MS, Rosman A, et al. Clinical and economic implications of upper gastrointestinal adverse events in Asian rheumatological patients on long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21(5):943–51.

Shafi S, Collinsworth AW, Copeland LA, Ogola GO, Qiu T, Kouznetsova M, et al. Association of opioid-related adverse drug events with clinical and cost outcomes among surgical patients in a large integrated health care delivery system. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):757.

Riaz M, Brown JD. Association of adverse drug events with hospitalization outcomes and costs in older adults in the USA using the nationwide readmissions database. Pharm Med. 2019;33(4):321–9.

Liao PJ, Mao CT, Chen TL, Deng ST, Hsu KH. Factors associated with adverse drug reaction occurrence and prognosis, and their economic impacts in older inpatients in Taiwan: a nested case–control study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026771.

Iwasaki H, Sakuma M, Ida H, Morimoto T. The burden of preventable adverse drug events on hospital stay and healthcare costs in Japanese pediatric inpatients: the JADE study. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. 2021;15:117955652199583.

Katsuno H, Tachi T, Matsuyama T, Sugioka M, Aoyama S, Osawa T, et al. Evaluation of the direct costs of managing adverse drug events in all ages and of avoidable adverse drug events in older adults in Japan. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:761607.

Boostani K, Noshad H, Farnood F, Rezaee H, Teimouri S, Entezari-Maleki T, et al. Detection and management of common medication errors ininternal medicine wards: impact on medication costs and patient care. Adv Pharm Bull. 2019;9(1):174–9.

Lee MS, Lee JY, Kang MG, Jung JW, Park HK, Park HK, Kim SH, Lee EK. Cost implications of adverse drug event-related emergency department visits - a multicenter study in South Korea. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;20(1):139–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2019.1608825.

Kurle DG, Jalgaonkar SV, Daberao VN, Chikhalkar SB, Raut SB. Study of clinical and histopathological pattern, severity, causality and cost analysis in hospitalized patients with cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a tertiary care hospital. IJPSR. 2018;9(5):1857–64.

Slight SP, Seger DL, Franz C, Wong A, Bates DW. The national cost of adverse drug events resulting from inappropriate medication-related alert overrides in the United States. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(9):1183–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy066.

Gyllensten H, Hakkarainen KM, Hägg S, Carlsten A, Petzold M, Rehnberg C, et al. Economic impact of adverse drug events – a retrospective population-based cohort study of 4970 adults. Brusic V, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092061.

Natanaelsson J, Hakkarainen KM, Hägg S, AnderssonSundell K, Petzold M, Rehnberg C, et al. Direct and indirect costs for adverse drug events identified in medical records across care levels, and their distribution among payers. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(6):1151–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.11.008.

McCarthy BC, Tuiskula KA, Driscoll TP, Davis AM. Medication errors resulting in harm: using chargemaster data to determine association with cost of hospitalization and length of stay. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(23_Supplement_4):S102-7.

Spector WD, Limcangco R, Furukawa MF, Encinosa WE. The Marginal Costs of Adverse Drug Events Associated With Exposures to Anticoagulants and Hypoglycemic Agents During Hospitalization. Med Care. 2017;55(9):856–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000780.

Batel-Marques F, Penedones A, Mendes D, Alves C. A systematic review of observational studies evaluating costs of adverse drug reactions. CEOR. 2016;8:413–26. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S115689.

Hug BL, Keohane C, Seger DL, Yoon C, Bates DW. The costs of adverse drug events in community hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(3):120–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38016-1.

Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Beghi E, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(10):718–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008.

Liu JLY. The economic burden of coronary heart disease in the UK. Heart. 2002;88(6):597–603. https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.88.6.597.

Lidgren M, Wilking N, Jönsson B. Cost of breast cancer in Sweden in 2002. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(1):5–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-006-0003-8.

Xu X, GrossettaNardini HK, Ruger JP. Micro-costing studies in the health and medical literature: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-47.

Austin PC. Comparing paired vs non-paired statistical methods of analyses when making inferences about absolute risk reductions in propensity-score matched samples. Statist Med. 2011;30(11):1292–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4200.

Haute Autorité de la Santé (HAS). Choices in methods for economic evaluation. 2020. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-11/methodological_guidance_2020_-choices_in_methods_for_economic_evaluation.pdf. Cited 2022 Sep 15.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Bogdan Cireasa, Medical Writer at Pharmacy Department, Nîmes University Hospital, France, for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The systematic literature review was conducted by MD and GLB. The manuscript was written by MD and GLB. CC, CRM, JMK reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No author has potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Durand, M., Castelli, C., Roux-Marson, C. et al. Evaluating the costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Health Econ Rev 14, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-024-00481-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-024-00481-y