Abstract

Background

Critical evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and clinical effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care models for women experiencing complex pregnancy is an important consideration in the review and reform of maternity services. Most studies either focus on women who experience healthy pregnancy or mixed risk samples. These results may not be generalised across the childbearing continuum to women with risk factors. This review critically evaluates studies that measure the cost of care for women with complex pregnancies, with a focus on method and quality.

Aims / objectives

To critically appraise and summarise the evidence relating to the combined cost-effectiveness, resource use and clinical effectiveness of midwifery continuity models for women who experience complex pregnancies and their babies in developed countries.

Design

Structured review of the literature utilising a matrix method to critique the methods and quality of studies.

Method

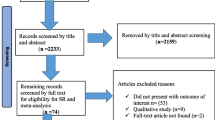

A search of Medline, CINAHL, MIDIRS, DARE, EMBASE, OVID, PubMed, ProQuest, Informit, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED) for the years 1994 – 2018 was conducted.

Results

Nine articles met the inclusion criteria. The review identified four areas of economic evaluation that related to women who experienced complex pregnancy and continuity of midwifery care. (1) cost and clinical effectiveness comparisons between continuity of midwifery care versus obstetric-led units; (2) cost of continuity of midwifery care and/or team midwifery compared to Standard Care; (3) cost-effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care for Australian Aboriginal women versus standard care; (4) patterns of antenatal care for women of high obstetric risk and comparative provider cost.

Cost savings specific to women from high risk samples who received continuity of midwifery care compared with obstetric-led standard care was stated for only one study in the review. Kenny et al. 1994 identified cost savings of AUS $29 in the antenatal period for women who received the midwifery team model from a stratified sub-set of high-risk pregnant woman within a mixed risk sample of 446 women. One systematic review relevant to the UK context, Ryan et al. (2013), applied sensitivity analysis to include women of all risk categories. Where risk ratio for overall fetal/neonatal death was systematically varied based on the 95% confidence interval of 0.79 to 1.09 from pooled studies, the aggregate annual net monetary benefit for continuity of midwifery care ranged extremely widely from an estimated gain of £472 million to a loss of £202 million. Net health benefit ranged from an annual gain of 15 723 QALYs to a loss of 6 738 QALYs. All other studies in this review reported cost savings narratively or within mixed risk samples where risk stratification was not clearly stated or related to the midwifery team model only.

Conclusions

Studies that measure the cost of continuity of midwifery care for women with complex pregnancy across the childbearing continuum are limited and apply inconsistent methods of economic evaluation. The cost and outcomes of implementing continuity of midwifery care for women with complex pregnancy is an important issue that requires further investigation. Robust cost-effectiveness evidence is essential to inform decision makers, to implement sustainable systems change in comparative maternity models for pregnant women at risk and to address health inequity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and background

Review and transformation of maternity service models have been on the policy agenda of the Australian Government for the past decade [1, 2]. An important policy goal is to expand women’s access to midwifery caseload continuity of care in both the public and private health sectors [3, 4]. Continuity of midwifery care is where a named midwife provides full antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care for a woman. The midwife provides physical, emotional and social support, flexible individualised care and robust multi-agency liaison. This enhances high quality perinatal care for mother and baby and strong working relationships with professionals [5]. Currently, only a small proportion of women are able to access continuity of midwifery care during their pregnancy [6].

Internationally, and in Australia, strong clinical and cost evidence already exist to support systemic implementation of continuity of midwifery care for women with healthy pregnancies [7,8,9,10]. However, in Australia the number of women who experience complex pregnancy is increasing [11]. In this review, complex pregnancy is defined as identified risk factors that place mother and/or baby at increased risk for adverse events. These can include biomedical and/or psychosocial risks, as identified by the woman and her care provider. Risk factors can be present at the start of pregnancy or arise at any time during the course of childbearing [12] . Evidence also shows significant inequity, poorer outcomes and associated increased healthcare costs for women who experience complex pregnancy. Outcomes for these women and their babies may potentially improve by increasing public health access to continuity of midwifery care models [13,14,15,16,17].

No previous systematic reviews have focused on women with complex pregnancies. To date, most systematic reviews of midwifery care have been conducted in the United Kingdom (UK) for low risk pregnancies. These reviews provide strong evidence for clinical and cost effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care (including birthing centres and home birth), as compared to obstetric - led units, but discrete economic analysis of outcomes and cost for pregnant women with risk factors were not included [9, 18,19,20,21,22,23]. Further, maternity services in many countries are not organised in the same configuration as in the UK, where clear delineation between continuity of midwifery care and obstetric-led units are an established feature.

Econometric models that applied productivity / efficiency frontiers and standard international resource ingredient approaches to develop predictive cost models, or other methods, for example, Net Benefit, were similarly limited [24, 25]. The implications of these studies is considered in the discussion in relation to costs of care for women who experience high risk pregnancy alongside clinical health outcomes in the midwifery continuity of care studies considered in this review. The lack of rigorous economic evaluation of different models of maternity care for women at high risk of complications has been emphasised in an integrated review examining cost data in relation to care provided in birth centres and at home with midwives [18]. This remains the case and provides a strong justification for the present review given the current evidence that show increasing rates of pregnancy complication and multiple complex maternal co-morbidity in Australia and elsewhere.

Capacity to improve maternity services to women with complicated pregnancy continues to pose a major challenge for the Australian health system [26,27,28]. This is particularly critical in rural and regional areas of the country where service options are limited and outcomes are significantly poorer than they are for women and babies in metropolitan areas [11, 29,30,31]. Critical evaluation of integrated evidence on the cost-effectiveness, resource use and clinical effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care for women who experience complexity therefore is an important consideration in quality review of maternity care.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this review is to critically appraise available literature and summarise the evidence related to cost, resource use, and clinical outcomes of care for women with complex pregnancies who received care in a continuity of midwifery care model compared with other maternity models.

This structured, integrated review will examine the available evidence for cost-effectiveness of antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care in continuity of midwifery care. It will critically evaluate the methods of these studies. This includes their capacity to support public health policy through expanded implementation and access to continuity of midwifery care for women who experience complications of pregnancy and childbearing and their babies.

Method

This review used a stepped structured approach to documenting the search strategy [32]. The Matrix Method was then applied to ensure a systematic framework for article collection, organisation and analysis [33, 34]. Application of PRISMA guidelines strengthened credibility and transparency of the reporting and assessment process [35]. Use of eight quality appraisal questions from the recommended checklist for appraising the costs and benefits of economic evaluation studies enabled robust synthesis of the results of studies [36].

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were primary research articles published in English language, peer-reviewed journals between the years 1994–2018. The 24-year time - frame marked the emergence of studies on the cost-effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care, including the first Australian studies [10, 37, 38]. Non-English language papers were excluded, as were those that focused exclusively on low resource countries.

Results

The classification of included studies within the evidence hierarchy is documented in Table 2.

Appraisal of studies

This review identified three systematic reviews that examined the cost and clinical effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care and obstetric-led maternity models. All three of these reviews were undertaken in the UK (Table 3).

A summary of the six primary studies included in this review, including study design is provided in Table 4. All studies were completed in Australia.

Results of these primary studies are reported in table 5.

Quality of studies

Economic evaluations undertaken alongside randomised controlled trials (RCT) constituted the most robust evidence for economic analysis of continuity of midwifery care models available. Importantly, four RCTs included in the systematic review by Sandall et al. [9] were conducted in Australia and included women of mixed pregnancy risk classification. The four Australian RCTs, were the only studies that examined cost results for continuity of midwifery care models that also included women with identified pregnancy risk factors [10, 37,38,39]. Two of the RCT studies identified their economic evaluations as cost analyses, Homer et al. [39], Kenny et al. [37]. One other was identified as a cost-effectiveness study on the NHS EED data base (Rowley et al. [38] and the remaining cost consequences analyses study, Tracy et al. [10], calculated per woman cost of care based on DRGs as well as direct and indirect costs for resource use.

The quality of cost, resource use and clinical effectiveness evidence in the primary studies included in this review therefore is high as they include mainly RCT evidence and also incorporated results from Levels III & IV of the evidence hierarchy. However, of the four RCT studies, three involved team midwifery models, as contrasted with continuity of care with a named midwife. In a team midwifery model a small group of midwives (up to 6 and no more than 8) provide care for identified women and the degree of continuity is not as high as in continuity of care with a named midwife. Other study designs considered cost evidence with varying levels of quality. Based on the NHMRC evidence hierarchy, the studies, in order of decreasing quality included cost analysis [40], and cost consequences analyses based on retrospective records audit [41].

While a number of studies were identified that used internationally validated ratios to model predictive costs for mode of birth and other interventions, these studies were excluded as they were not directly applied to continuity of midwifery care or women with identified pregnancy risk factors [42,43,44,45].

Four areas of economic evaluation that relate to women who experienced complex pregnancy were identified from the review:

-

1.

Comparisons of midwife-led versus obstetric consultant-led units for cost and clinical effectiveness

Two studies had data relevant to this theme. While cost models were based on trials that recruited women with low pregnancy risk, sensitivity analysis modelled cost for women of mixed pregnancy risk classification based on UK population data. In the two systematic reviews from the UK where continuity of midwifery care and obstetric consultant-led maternity models are common, an estimated mean cost saving for each eligible woman of £12.38 was found in the continuity of midwifery care model overall. This provided aggregate health savings of £1.16 million per year for the health system if only half of all eligible women received continuity of midwifery care [20]. However, it is of note that these results are highly sensitive to assumptions, particularly changes in the rate of fetal loss and neonatal death, as well as the midwife’s caseload. When sensitivity analysis was applied to include women of all risk categories and the risk ratio for overall fetal/neonatal death was systematically varied based on the 95% confidence interval of 0.79 to 1.09 from pooled studies, the aggregate annual net monetary benefit for continuity of midwifery care ranged extremely widely. This varied from an estimated gain of £472 million to a loss of £202 million. Net health benefit ranged from an annual gain of 15 723 QALYs to a loss of 6 738 QALYs. Additionally the midwife’s caseload needs to be sufficiently large to attain operational efficiencies, otherwise the cost per maternity increases. The conclusion therefore is that the evidence base for cost-effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care for women with pregnancy risk is limited [19, 20]. As stated, these findings are limited to the UK context where midwifery-led and obstetric-led units are an established feature of the health system. This is not the case in other contexts, including Australia.

-

2.

Cost of continuity of midwifery care and/or team midwifery compared to Standard Care (medical)

Over the past two decades economic evaluations conducted alongside RCTs in several Australian states have demonstrated cost saving and clinical effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care models compared with standard hospital care in the same setting [10, 37,38,39, 46]. Some of these studies focused on ‘team midwifery’ [37,38,39, 46] while others evaluated continuity of midwifery care models. In a ‘team model’ there is no primary care provider and the level of continuity is variable, compared to continuity of midwifery care models where named midwives provide services for women across the full continuum of antenatal, birth and postnatal care [9]. The cost evaluations of team midwifery and one cost evaluation of continuity of midwifery care in Australia have included pregnant women of mixed-risk status [10]. However, all these studies, with the exception of Kenny et al. [37] did not stratify results specific to women with high-risk pregnancy.

The most recent mixed-risk Australian trial identified a median cost saving of A$566 for women who received continuity of midwifery care compared to standard hospital care services, these savings cannot be generalised to high risk groups [10]. This trial identified safe outcomes for mothers and babies but no significant difference between continuity of midwifery care and standard care for primary outcomes of epidural analgesic use during labour, number of CS, instrumental vaginal births or unassisted vaginal births. Earlier rigorous cost analysis of community-based continuity of midwifery care model for all-risk women in Australia also identified mean cost savings per woman of A$804 in the continuity of midwifery care model. This included a significant difference in the rate of CS [39]. After neonatal costs were excluded in this study, mean cost savings continued to favour women and babies in the continuity of midwifery care model by A$139 [39]. While it was not possible to determine optimal service volume based on caseload numbers, the number of women booked for care in the continuity of midwifery care model was one of the important keys to cost-effectiveness. The reason for this relates to efficiency and savings generated by the volume of women able to be allocated to a maternity model in relation to the staff ratio required to provide maternity services [20, 47].

Earlier team midwifery RCT studies identified reduced levels of birth intervention in addition to modest cost savings for women of all-risk. One study identified as a cost-effectiveness study used Australian Diagnostic Related Groups ‘top-down costing’ that showed a mean cost reduction for birth of 4.5% for women in the midwifery group, [38]. The other study, a cost analysis, analysed discrete costs (‘bottom-up costing’) for each episode of service (i.e. antenatal, birth, and postnatal care) in the midwifery model versus standard hospital care [37]. Specific cost for high- and low-risk pregnancy episodes of care is shown in Table 4. Kenny et al. [37] is the only study identified that separated the risk stratification profile of women in their all-risk pregnancy sample in relation to costs. All the studies suggested a cost saving in intrapartum care in the midwifery model. One study suggested higher cost and one study showed no difference in cost of postnatal care in the midwifery model compared with the medical-led model. Cost results for postnatal care also were not stratified as specific to women with pregnancy risk.

-

3.

Cost-effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care for Aboriginal women versus standard care

Two studies attempted to measure the cost of continuity of midwifery care in identified Australian populations with higher pregnancy risk status. Gao et al. [41] used a retrospective baseline cohort measured against a prospective cohort of pregnant Aboriginal women (all-risk status) to identify cost changes from the first antenatal visit through to six weeks postpartum after introduction of continuity of midwifery care. While there was a trend for cost savings of A$703 for women at 6 weeks, these were not significantly different from baseline costs. Limitations of the study included small sample size, cost assumptions (hostel and transport were not included), and missing data (51% of all cases). While no significant difference in major birth outcomes was identified antenatal attendance and hospital admissions increased, and average length of special care nursery stay for the babies of the women decreased.

An earlier cost analysis of a metropolitan, Aboriginal-controlled, continuity of midwifery care service (all-risk) estimated direct program costs and downstream savings in the health sector of A$1,200 per woman [40]. Downstream savings projected longer - term cost benefits that were gained, for example, from reductions in resource use experienced by associated services. The study used Australian National DRG cost weights [48] and cost data from Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme [49] and sensitivity analysis to model uncertainty. Costs included were broader than those used in conventional economic analyses. Among the additional cost considerations were clinical outcomes for birth, antenatal attendance in a subsequent pregnancy, and subtraction of cost savings to other centres. While more recent clinical evaluation of midwifery models of care for Aboriginal women have demonstrated significant improvement in infant birthweight and perinatal survival, specific cost analysis of these benefits have not yet been undertaken as part of the studies [15, 50].

-

4.

Patterns of antenatal care for women of high obstetric risk and comparative provider costs

In this review antenatal care provided by midwives for high risk and mixed risk samples showed reduced cost in three RCT studies [20, 37, 39] and increased cost in two others (non-RCT) [40, 41](as shown in Tables 3 and 4).

This is consistent with a cochrane review of patterns of antenatal care which showed, among different providers of antenatal care (midwife, general practitioner, obstetrician), primary outcome measures of low birthweight, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, severe postpartum anaemia, and treated urinary tract infection (all high risk factors for pregnancy complications including pre-term birth) demonstrate similar clinical effectiveness [51, 52].

Discussion

Increasingly health services need to justify quality outcomes as well as value for money [53,54,55,56]. Quality maternity care is especially important for women who experience high risk pregnancy as inequitable health outcomes for these mothers and babies pose additional policy and service implementation challenges for government [57, 58]. Moreover, decision-makers often grapple to determine the most effective and sustainable models of care to close these gaps [28, 59, 60]. In high resource settings such as Australia, many women with the most significant health inequities also experience pregnancy complications with long-term comorbidity [11, 30]. The public health burden, including the cost of chronic disease for these women, their babies and the health system is higher and often lifelong [61]. Economic evaluation to inform decision-making regarding the comparative cost-effectiveness of different maternity models across the continuum of childbearing therefore should be a high priority.

This review demonstrated that there are few studies specific to evaluating cost-effectiveness of midwifery continuity of care models for women who experience high-risk pregnancy relative to other models of maternity care, including standard and traditional obstetric led models. Of the studies included, significant limitations and caveats apply. Inter-country comparison of cost and models of maternity care between health systems that do not share the same features prohibit comparative generalisability of both outcomes and models of care, including the costs attributable to different models and systems. The costs and outcomes may vary widely according to structural factors such as funding model and workforce arrangements and the influence of demographic features and characteristics of woman who experience high - risk pregnancy within the study samples.

A strong international evidence base supports woman’s early access to antenatal care, pre-natal education and health promotion strategies provided by midwives as an effective intervention to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes when integrated with other specialised health and social support services [57, 58, 60]. Poor access to antenatal care, including delayed attendance for the first visit is associated with higher rates of pre-term birth and low birthweight infants and increased interventions in late pregnancy, all of which have been found to negatively impact cost [11, 62]. This review found a small limited evidence-base to support the delivery of cost -effective antenatal care by midwives to women with identified pregnancy risk factors that deliver equivalent and/or improved health outcomes for them and their babies when compared to standard or traditional models of obstetric care [10, 37,38,39]. Additionally, while earlier systematic review has shown that low-risk pregnant women who receive midwifery-led care require fewer antenatal visits, generating significant short-term cost savings for services [52], this is not always the case where women have identified medical and psychosocial risk factors.

Two studies included in this review identified higher antenatal costs associated with increased frequency of visits for women identified with higher pregnancy risks who may otherwise experience increased morbidity and mortality in pregnancy and childbearing [40, 41]. Consideration of overall ‘downstream’ savings’ within midwifery continuity of care models for women with risk factors therefore is a relevant consideration. It is recommended that future analyses include measures and methods broader than those used in conventional economic analyses, for example, longer term modelling of disutility costs associated with onset of chronic disease states [63]. Downstream savings have been demonstrated to be important in estimating both program and health sector costs accurately, particularly where access and significant health inequities have been identified [40]. The limitations of the current studies in measuring these effects could be assessed by applying different methods in health economics. Discrete choice experiment (DCE), for example, has been proposed as a more reliable method for eliciting women’s preferences for maternity care [64]. DCE assesses and measures the costs associated with consumer preferences for health care by asking pregnant women what they want.

With respect to intrapartum care, while studies show resource inputs and cost ratios for mode of birth to be relatively consistent among countries over time, recent comparison of the costs of childbirth show significant cross-country variation. Factors that have been associated with inter-country cost increases relate specifically to workforce salary rates and provider charges in fee-based health systems [24]. Further, overuse and underuse of birth interventions, for example surgical birth, which may be more prevalent in women who experience high risk pregnancy also demonstrate significant variation and remain subject to multiple influences, including health provider, health system, and funding model [25, 65]. Data from all-risk pregnancies also show that birth by caesarean section (CS) costs substantially more than vaginal birth [66]. International cost ratios for mode of birth validated in Scotland, England, and Australia indicate the incremental equivalent cost ratios as: vaginal birth = 1; instrumental birth = 1.3; caesarean = 2.5 [44]. However, in this review no studies applied or modelled these cost variations for intervention nor linked health outcomes specific to women with pregnancy risk factors in comparative models of maternity care. Despite this, outcomes in some of the studies included in this review show that costly intrapartum interventions, including surgical birth in women with pregnancy risk factors may be safely reduced in intrapartum care for some women who receive continuity of midwifery care thereby also resulting in some cost saving [37,38,39].

Place of birth is strongly associated with cost [22, 23, 67]. Cost is increased in hospital settings and compounded in facilities with fragmented models of care [68]. However, women with a complex pregnancy currently access many fragmented maternity models and a significant amount of their care in hospitals [11, 31]. The model of maternity care therefore is an important issue when considering cost. The recent introduction of a national maternity care classification system (MaCCs) by the Australian government will enable improved comparison of outcomes and cost between midwifery continuity of care and other maternity models [69, 70] .

In different maternity models and among different provider groups, increased rates of surgical birth, especially caesarean section, and other routine medical practices associated with the cascade of intervention in childbirth increase cost and morbidity [9, 43]. Longer bed stay associated with over intervention for women and their infants results in increased rate and length of hospitalisation, including admission and readmissions, and additional cost in the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum periods [31, 69, 71]. The potential savings from improved clinical outcomes generated through midwifery continuity of care across the childbearing continuum should be further evaluated in woman who experience high risk pregnancy and should include the postnatal period [62].

Most published studies have focused on women considered low risk for developing complications and receiving midwifery-led care. Robust evidence from international and Australian studies demonstrates improved cost and clinical outcomes for these women and their babies across a number of key areas, notably physiological vaginal birth [9, 20].

Significantly, midwifery models for low risk women have shown a trend to variable cost saving in health service models where volume is sufficient to achieve efficiency and economies of scale [19, 20]. Savings accrue where caseloads are maintained at an upper threshold of 40 women per midwife per annum [20]. High-volume institutional settings may optimise savings in these models when antenatal hospitalisation rates are kept low, vaginal birth rate is maximised, women and infants undertake early discharge, and receive postnatal follow-up at home or in the community [7, 10, 20, 72, 73]. However, whether these clinical and cost benefits can be extended through greater use of midwifery continuity of care for women who experience pregnancy risk factors require further evaluation. Discrete economic evaluation of midwifery continuity of care in the postnatal period for women with pregnancy risks, as compared to other maternity models including obstetric and standard care was identified as significantly lacking.

In the limited studies examined in this review, diversity in study design and variation in the quality of the results generated often negate reliable comparison of cost results. Where studies include women of mixed pregnancy risk, variation and inconsistency of both study design and the methods applied precluded reliable, comprehensive cost comparisons across the maternity care continuum for woman with pregnancy risk factors. Robust economic evaluations conducted alongside a RCT were considered to have high validity and reliability. None, however, focused exclusively on women with complicated pregnancy. This was in contrast to non-randomised retrospective audit studies [40, 41]. Studies in which a variety of statistical imputation methods or expert opinion or estimates were used to account for missing data created further challenges for reliability in establishing the cost accuracy results of the economic evaluation [41, 74].

Methodological challenges were identified in this review. The first of these was selective risk sampling. Of studies included in this review some used “mixed risk” pregnancy samples that did not stratify clinical results or cost specific to the high-risk sub-set within the sample, thereby limiting generalisability of results. A second challenge included the variables selected for measurement in each study. The variables selected showed significant variation. Accurate measurement of variables depended on the data available and the reliability of the data sources. The data sources of studies included in this review demonstrated wide fluctuation in reliability and quality across different time horizons making comparison of outcomes and cost unreliable.

Inconsistencies that compounded the methodological challenges outlined above also were identified in relation to the various type of economic evaluations of maternity care identified in this review – cost-effectiveness, cost consequences analysis, and economic synthesis. These included the use of varying cost methodology and study assumptions. For example, ‘top-down’ costing approaches that used diagnostic related groups cost weights reflected activity-based funding models [10, 38], as contrasted with ‘bottom-up’ costing that incorporated measurement of specified resource components – for example equipment, consumables, staff salaries, caseload numbers, infrastructure costs [37, 46]. Moreover, sensitivity analysis was included in some of the economic evaluations and not in others. Incomplete or significant amounts of missing data replaced with estimates also called into question the reliability and transferability of cost estimate results. Even synthesis of results from RCTs that applied the most rigorous health economic measures of INB, NMB, NHB and QALYs in the systematic review conducted by Ryan et al [20] estimated projected costs for midwife continuity of care that fluctuated from significant aggregate saving and QALY gains to significant aggregate loss and QALY reductions when assumptions were challenged.

Conclusion

Robust evaluation and comparative cost performance of alternative models of maternity care is an important consideration in the provision of safe, quality maternity services for women who experience complicated pregnancy. While it is well known that poor outcomes at start to life contribute to long-term chronic disease states that is costly for the health system, optimising clinical effectiveness outcomes and cost efficiency for care of women who experience complex pregnancy requires higher prioritisation. This review found limited evidence to support the cost-effectiveness of midwifery continuity of care for women with complex pregnancy. Further evaluation of cost, resource use and clinical outcomes comparative to other models of maternity care is critical. Further, this review shows that those studies that have attempted to measure these costs demonstrate a range of inconsistencies. The application of inconsistent method undermines valid cost comparison of maternity models in developed countries. This remains an ongoing challenge for policy makers and service providers in implementing system change.

Equitable access to continuity of midwifery care is an important issue for women with pregnancy complication. Evidence on the comparative cost-effectiveness resource use and clinical outcomes delivered through new maternity services is essential to the development of sustainable maternity models. This issue has relevance in an increasing number of settings in Australia and other high resource countries in which services that address healthy start to life are critical to reduce current maternal newborn health inequity, and to meet the needs and expectations of women and their families.

Abbreviations

- AUS: :

-

Australia

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- DCE:

-

Discrete choice experiment

- DRG:

-

Diagnostic Related Group

- INB:

-

Incremental Net Benefit

- NHB:

-

Net Health Benefit

- NHMRC:

-

National Health Medical Research Council

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NICE:

-

National Institute Clinical Excellence

- NMB:

-

Net Monetary Benefit

- QALY:

-

Quality Adjusted Life Year

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Australian Government. Improving Maternity Services in Australia: The report of the Maternity Services Review. Canberra: Department of Health & Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia; 2009. p. 1-68.

Commonwealth of Australia. National Maternity Services Plan. Canberra: The Australian Health Ministers' Conference; 2011.

Newnham E. Midwifery directions: The Australian maternity services review. Health Sociology Review. 2010;19(2):245–59.

Wilkes L, Gamble J, Adam G, Creedy D. Reforming maternity services in Australia: Outcomes of a private practice midwifery service. Midwifery. 2015;31(10):935–40.

England NHS. Implementing Better Births: Continuity of Carer. London: NHS; 2017.

Dawson K, McLachlan H, Newton M, Forster D. Implementing caseload midwifery: exploring the views of maternity managers in Australia – A national cross-sectional survey. Women and Birth. 2016;29(3):214–22.

McLachlan H, Forster DA, Davey MA, Farrell T, Gold L, Biro M, et al. Effects of continuity of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) on caesarean section rates in women of low obstetric risk: the COSMOS randomised controlled trial. British J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119(12):1483–92.

Homer C. Models of maternity care: evidence for midwifery continuity of care. Med J Aust. 2016;205(8):370–4.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004667.

Tracy S, Hartz D, Tracy M, Allen J, Forti A, Hall B, et al. Caseload midwifery care versus standard maternity care for women of any risk: M@NGO, a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2013;382:1723 - 32, Published online September 17, 2013 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61406-3.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s mothers and babies 2016—in brief. Canberra: AIHW; 2018.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What are the factors that put a pregnancy at risk? United States: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016 [Available from: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/high-risk/conditioninfo/factors.

McNeill J, Lynn F, Alderdice F. Public health interventions in midwifery: a systematic review of sytematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:955.

Small R, Roth C, Raval M, Shafiei T, Korfker D, Heaman M, et al. Immigrant and non-immigrant women's experiences of maternity care: a systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:152 2014.

Bertilone C, McEvoy S. Success in Closing the Gap: favourable neonatal outcomes in a metropolitan Aboriginal Maternity Group Practice Program. Med J Aust. 2015;203(6):262 e1 - .e7.

Rayment-Jones H, Murrells T, Sandall J. An investigation of the relationship between the caseload model of midwifery for socially disadvantaged women and childbirth outcomes using routine data - A retrospective, observational study. Midwifery. 2015;31:409–17.

de Jonge A, Sandall J. Improving research into models of maternity care to inform decision making. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002135.

Henderson J, Petrou S. Economic Implications of Home Births and Birth Centers: A Structured Review. Birth. 2008;35:136–46.

Devane D, Brennan M, Begley C, Clarke M, Walsh D, Sandall J, et al. Socioeconomic Value of the Midwife: A systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis and economic analysis of midwife-led models of care. London: Royal College of Midwives; 2010.

Ryan P, Revill P, Devane D, Normand C. An assessment of the cost-effectiveness of midwife-led care in the United Kingdom. Midwifery. 2013;29:368–76.

Sutcliffe K, Caird J, Kavanagh J, Rees R, Oliver K, Dickson K, et al. Comparing midwife-led and doctor-led maternity care: a systematic review of reviews. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(11):2376–86.

Schroeder E, Patel N, Keeler M, Rocca-Ihenacho L, Macfarlane A. The Economic Costs Of Intrapartum Care In Tower Hamlets: A Comparison Between The Cost Of Birth In A Freestanding Midwifery Unit And Hospital For Women At Low Risk Of Obstetric Complications. Midwifery. 2017;45:28–35.

Schroeder E, Petrou S, Patel N, Hollowell J, Puddicombe D, Redshaw M, et al. Cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth in woman at low risk of complications: evidence from the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2012;344(e2292):1–13.

Bellanger M, Or Z. What can we learn from a cross-country comparison of of the costs of child delivery? Health Econ. 2008;17(Suppl. 1):S47–57.

Gibbons L, Belizan J, Lauer J, Betran A, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The Global Numbers and Costs of Additionally Needed and Unnecessary Caesarean Sections Performed per Year: Overuse as a Barrier to Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010.

Homer C, Biggs J, Vaughan G, Sullivan E. Mapping maternity services in Australia: Location, classification and services. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35:222–9.

Yelland J, Riggs E, Small R, Brown S. Maternity services are not meeting the needs of immigrant women of non-English speaking background: Results of two consecutive Australian population based studies. Midwifery. 2015;31(7):664–70.

Kildea S, Tracy S, Sherwood J, Magick-Dennis F, Barclay L. Improving maternity services for Indigenous women in Australia: moving from policy to practice. Med J Aust. 2016;205(8):375–9.

Pilcher J, Kruske S, Barclay L. A review of rural and remote health service indexes: are they relevant for the development of an Australian rural birth index? BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;2014(14):548.

Monk A, Harris K, Donnolley N, Hilder L, Humphrey M, Gordon A, et al. Perinatal deaths in Australia 1993-2012 (AIHW Perinatal deaths series no. 1. Cat. no. PER 86). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra; 2016.

National Health Performance Authority. Healthy Communities: Child and maternal health in 2009 - 2012. Sydney: National Health Performance Authority; 2014.

Kable A, Pich J, Maslin-Prothero S. A structured approach to documenting a serach strategy for publication: A 12 step guideline for authors. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32:878–86.

Torraco R. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2005;4:356–67.

Denyer D, Pilbeam C. Doing a literature review in business and management. Presentation to the British Academy of Managment Doctoral Symposium, Liverpool: UK; 2013.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6).

National Health and Medical Research Council. How to compare the costs and benefits: evaluation of the economic evidence. Australian Government Publishing Service; 2001.

Kenny P, Brodie P, Eckermann S, Hall J. Westmead Hospital Team Midwifery Project Evaluation Final Report. Sydney: Centre for Health Economics Research and Evaluation, University of Sydney; 1994.

Rowley M, Hensley M, Brinsmead M, Wlodarczyk J. Continuity of care by a midwife team versus routine care during pregnancy and birth: a randomised trial. Med J Aust. 1995;163(6):289–193.

Homer C, Matha DV, Jordan LG, Wills J, Davis GK. Community-based continuity of midwifery care versus standard hospital care: a cost analysis. Aust Health Rev. 2001a;24(1):85–93.

Jan S, Conaty S, Hecker R, Bartlett M, Delaney S, Capon T. An holistic economic evaluation of an Aboriginal community - controlled midwifery program in Western Sydney. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(1):14–21.

Gao Y, Gold L, Josif C, Bar-Zeev S, Steenkamp M, Barclay L, et al. A cost-consequences analysis of a Midwifery Group Practice for Aboriginal mothers and infants in the Top End of the Northern Territory Australia. Midwifery. 2014;30(4):447–55.

Stewart M, McCandlish HJ, Brocklehurst P. Report of a structured review of birth centre outcomes: review of evidence about psychosocial and economic outcomes for women with straightforward pregnancies who plan to give birth in a midwife-led birth centre, and outcomes for their babies. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; 2005.

Tracy S, Welsh A, Hall B, Hartz D, Lainchbury A, Bisits A, et al. Caseload midwifery compared to standard or private obstetric care for first time mothers in a public teaching hospital in Australia: a cross sectional study of cost and birth outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:46.

Tracy S, Tracy M. Costing the cascade: estimating the cost of increased obstetric intervention in childbirth using population data. BJOG. 2003;110:717–24.

Petrou S, Glazener C. The economic costs of alternative modes of delivery during the first two months postpartum: results from a Scottish observational study. Br. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109(2):214–7.

Homer C, Davis G, Brodie P, Sheehan A, Barclay L, Wills J, et al. Collaboration in maternity care: a randomised controlled trial comparing community-based continuity of care with standard hospital care. BJOG. 2001b;108:16–22.

Sandall J, Page L, Homer C, Leap N. Chapter 2 Midwifery continuity of care: what is the evidence? In: Homer C, Brodie P, Leap N, editors. Midwifery Continuity of Care: A Practical Guide. Chatswood NSW: Elsevier Australia; 2008. p. 25–46.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. National Hospital Cost Data Collection. Canberra; 2010.

Australian Government Department of Human Services. Medicare Online 2014 [Available from: https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/subjects/medicare-services.

Hickey S, Roe Y, Gao Y, Nelson C, Carson A, Currie J, et al. The Indigenous Birthing in an Urban Setting study: the IBUS study. A prospective birth cohort study comparing different models of care for women having Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies at two major maternity hospitals in urban South East Queensland, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:431.

Villar J, Ba'aqeel H, Piaggio G. WHO randomised controlled trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. The Lancet. 2001;357:1551–64.

Patterns of routine antenatal care for low risk women (Cochrane Review) [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons. 2007.

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. The Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45.

Berwick D, Nolan T, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health And Cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69.

Porter M. The Strategy to Transform Health Care and the Role of Outcomes. OECD Policy Forum, People at the Centre: The Future of Health; 2017.

All Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health. Triple Impact Report. London; 2016.

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M. Beyond too little, too late and too much too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet 2016; published online September 15. 2016.

Van Lerberghe W, Matthews Z, Achadi E, Ancona C, Campbell J, Channon A, et al. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. The Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1215–25.

COAG. Health Council. National Framework for Maternity Services Project. 2017.

ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, Downe S, Fauveau V, Fogstad H, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. The Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1226–35.

Moore T, Arefadib N, Deery A, West S. The First Thousand Days: An Evidence Paper. Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute: Parkeville, Victoria; 2017.

Homer C, Friberg IK, Dias MAB, ten Hoope-Bender P, Sandall J, Speciale AM, et al. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. The Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1146–57.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 3rd ed. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Petrou S, McIntosh E. Commentary: Using Stated Preference Discrete Choice Experiments to Elicit Women's Preferences for Aspects of Maternity Care. Birth. 2011;38(1):47–8.

Betrán A, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, Mohiddin A, Opiyo N, Torloni M, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. The Lancet. 2018;392:1358–68.

Petrou S, Henderson J, Glazener C. Economic aspects of caesarean section and alternative modes of delivery. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;15(1):145–63.

Birthplace in England Collaborative Group BP, Hardy, P, Hollowell, J et al. . Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2011;343:d7400.

Scarf V, Catling C, Viney R, Homer C. Costing Alternative Birth Settings for Women at Low Risk of Complications: A Systematic Review. PLoSOne. 2016;11(2):e0149463.

National Health Performance Authority. Hospital Performance: Costs of acute admitted patients in public hospitals in 2011 - 2012 Technical Supplement. Canberra 2015; 2015.

Donnolley N, Butler-Henderson K, Chapman M, Sullivan E. The development of a classification system for maternity models of care. Health Inf Manag J. 2016;45(2):64–70.

National Health Performance Authority. Hospital Performance: Length of stay in public hospitals in 2011 - 2012. 2013.

Kenny C, Devane D, Normand C, Clarke M, Howard A, Begley C. A Cost-Comparison of Midwife-led Compared with Consultant-led Maternity Care in Ireland (The MIDU Study). Midwifery. 2015;31(11):1032–8.

Henderson J, McCandlish R, Kumiega L, Petrou S. Systematic review of economic aspects of alternative modes of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;108:149–57.

Gelman A, Hill J. Chapter 25 Missing-data imputation. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel / Hierarchical Models. UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. 529-43.

Acknowledgements

Doctoral research of the first author was supported through a Midwifery Fellowship provided by WCH Foundation SA.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received to prepare this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RDF, DKC & EC conceptualized the manuscript. RDF searched data bases and drafted the manuscript. RDF, DKC & EC each contributed to critically reviewed drafts of the manuscript. RDF & DKC reviewed and refined Tables. RDF coordinated revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Donnellan-Fernandez, R.E., Creedy, D.K. & Callander, E.J. Cost-effectiveness of continuity of midwifery care for women with complex pregnancy: a structured review of the literature. Health Econ Rev 8, 32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-018-0217-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-018-0217-3