Abstract

Background

Amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction (AIT) is a side-effect associated with the use of Amiodarone for the treatment of refractory arrythmias. Resulting hyperthyroidism can precipitate cardiac complications, including cardiac ischemia and myocardial infarction, although this has only been described in a few case reports.

Case presentation

We present here a clinical scenario involving a 66-year-old male Caucasian patient under Amiodarone for atrial fibrillation, who developed AIT. In the presence of dyspnea, multiple cardiovascular risk factors and ECG abnormalities, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, showing inferobasal hypokinesia. This led to further investigations through a cardiac PET-CT, where cardiac ischemia was suspected. Ultimately, the coronary angiography revealed no abnormalities. Nonetheless, these extensive cardiologic investigations led to a delay in initiating an emergency endovascular revascularization for acute-on-chronic left limb ischemia. Although initial treatment using Carbimazole was not successful after three weeks, the patient reached euthyroidism after completion of the treatment with Prednisone so that eventually thyroidectomy was not performed. Endovascular revascularization was finally performed after more than one month.

Conclusions

We discuss here cardiac abnormalities in patients with AIT, which may be due to relative ischemia secondary to increased metabolic demand during hyperthyroidism. Improvement of cardiac complications is expected through an optimal AIT therapy including medical therapy as the primary approach and, when necessary, thyroidectomy. Cardiac investigations in the context of AIT should be carefully considered and may not justify delaying other crucial interventions. If considered mandatory, diagnostic procedures such as coronary angiography should be preferred to functional testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amiodarone is a class III anti-arrhythmic drug widely used in clinical practice as second-line therapy for refractory ventricular and supra-ventricular arrythmias [1]. Thyroid dysfunction under amiodarone affects up to 20% of treated patients, either hyperthyroidism/thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism [2, 3]. Two types of Amiodarone-Induced Thyroid Dysfunction (AIT) are distinguished: type 1 AIT is a form of iodine-induced hyperthyroidism typically arising in a gland with underlying functional autonomy, while type 2 AIT is a destructive thyroiditis developing in a normal gland. The treatment of choice usually consists of a combination of thionamides and glucocorticoids, as distinguishing between the two types of AIT can be challenging [2, 4, 5]. However, resolution of hyperthyroidism takes usually several weeks to months.

Amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism may be associated to serious cardiac complications. In particular, hyperthyroidism can lead to cardiac ischemia and even to a secondary myocardial infarction [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. In addition, hyperthyroidism is also associated with a pro-coagulant state and can aggravate cardiac and limb ischemia [13, 14]. Both conditions might benefit from an early thyroidectomy.

Therefore, one challenge resides in the indication and the optimal timing for the thyroidectomy. Indeed, anaesthetizing a patient with a decreased hemodynamic status or suspicion for cardiac ischemia can be challenging and the need for further investigations with the aim to mitigate potential intra- or peri-operative complications should be balanced with the delay of the thyroidectomy.

We describe here a clinical scenario with AIT, suspected cardiac ischemia and acute-on-chronic limb ischemia. Extensive cardiac investigations were carried out, which revealed false-positive functional imaging, probably due to increased cardiac metabolism, resulting in a delay in revascularization of limb ischemia. Our aim is to discuss the rationale of such investigations and the benefits of an early thyroidectomy.

Materials and methods

In accordance with ethical guidelines, written informed consent was obtained from the patient involved for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal. The patient's identity has been rigorously protected, and any potentially identifying information has been appropriately anonymized to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

In order to discuss the association between hyperthyroidism and cardiac ischemia, and the indication for cardiac investigations in AIT, we conducted a literature research on PubMed and MEDLINE using the following keywords: “Amiodarone-Induced Thyroid Dysfunction”, “hyperthyroidism”, “cardiac ischemia”, “thyroidectomy”. Only articles written in English were considered for this case report.

Case presentation

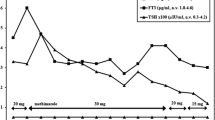

Our patient is a 66-years old male Caucasian patient known for active smoking (~ 60 pack years), hypertension and dyslipidemia, who presented with severe hyperthyroidism induced by amiodarone (given for the treatment of atrial fibrillation). At the time of diagnosis, he presented with tachycardia but no hemodynamic instability, NYHA stage 2 dyspnea and unexplained weight loss. Initial laboratory work-up showed suppressed TSH < 0.05 mUI/l, free T3 13.9 pmol/l and free T4 72 pmol/l. Anti-TSH antibodies were negative. Thyroid ultrasound showed a hypovascular thyroid and the absence of thyroid nodules. Thyreostatic treatment with Carbimazole tablets 60 mg/day was initiated. After 3 weeks, the patient was still hyperthyroid, so prednisone tablets 40 mg/day were added.

Meanwhile, the patient displayed obliterative arteriopathy of the lower limbs, stage IIA Fontaine in the left lower limb, with distal embolization of a tight stenosis of the homolateral common iliac artery, stage I Fontaine in the right lower limb. Although left limb ischemia was not critical, it required a rapid endovascular revascularization. Thyroid normalization is essential prior to vascular intervention, due to the procoagulant state associated with hyperthyroidism.

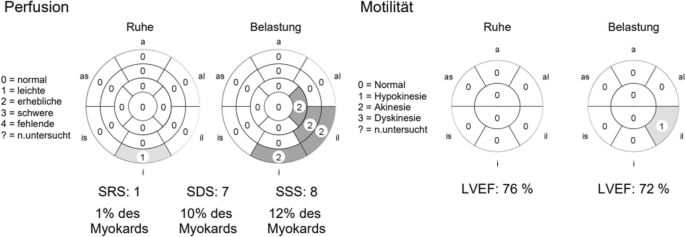

In the absence of response to drug treatment after three weeks, thyroidectomy was discussed. In this context, and due to a high cardiovascular risk associated with dyspnea, a transthoracic echocardiogram showed inferobasal hypokinesia and a cardiac PET-CT was performed, showing suspected inferobasal and inferoapical ischemia (Fig. 1).

Cardiac PET scan findings of our patient. No scar but evidence of infero-lateral to infero-apical ischemia (Perfusion). Localized decreased flow reserve in ischemia area. Preserved left ventricular pump function (Motilität) with normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). SRS summed rest score, SDS summed difference score, SSS summed stress score, a apical, as apico-septal, al apico-lateral, is infero-septal, il infero-lateral, i inferior

After multidisciplinary discussion involving cardiology, anesthesiology, angiology and endocrinology, it was decided to perform coronary angiography as soon as possible to rule out cardiac ischemia. Coronary angiography showed no abnormalities requiring revascularization.

Following the various cardiac investigations and the related delay, the evolution of his thyroid function was resolved after more than a month (TSH 0.91mUI/l, free T4 14.2pmol/l, free T3 3.2pmol/l) without surgery, and the patient underwent successful endovascular revascularisation for his peripheral arterial disease.

Discussion

The clinical scenario presented here emphasizes a patient exhibiting amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism, requiring prompt intervention to mitigate potential complications, including acute limb ischemia. However, concerns regarding cardiac ischemia introduced a slowdown in the treatment process. Ultimately, thyroidectomy was not performed and vascular interventions were postponed until euthyroid status was achieved. In this situation, where the treatment of hyperthyroidism and peripheral arterial disease are decisive, it is of interest to discuss the indication for additional cardiologic investigations, including cardiac PET scan. Especially considering the impact of hyperthyroidism on cardiac muscle [15, 16], and the recent literature suggesting that patients with hyperthyroidism-related cardiac complications might benefit from an early thyroidectomy [17,18,19,20]. Indeed, PET scan in patients with hyperthyroidism may display false positive results for coronary artery disease due to hypermetabolism with consecutive relative ischemia.

AIT can be associated with cardiovascular complications, including rhythm disorders such as tachycardia and atrial fibrillation, along with high-output congestive heart failure, among others [15, 16]. In more uncommon instances, it may also result in cardiac ischemia and acute myocardial infarction [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Thyroid hormones induce cell proliferation in the vascular wall typically leading to cardiac hypertrophy with progressively worsening high-output congestive heart failure, as evidenced by a decrease in echocardiography-measured left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [21].

Cardiac Ischemia related to hyperthyroidism is rarely described in the literature and is the topic of older publications and a limited number of case reports [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. It has been particularly described in elderly patients with coronary artery disease [22]. The mechanisms explaining cardiac ischemia in patients with hyperthyroidism remain unclear, but they might involve an increased myocardial oxygen demand related to cardiac hypertrophy, temporary coronary artery occlusion in a procoagulant state and vasoconstriction / vasospasm. Although the molecular mechanism remains unclear, there is some similarity with the clinical impact of excess catecholamines on the suffering of cardiac muscle. This may be due to thyroid hormones, which enhance the sympathetic nervous system by increasing the sensitivity of beta receptors [23].

Indeed, hyperthyroidism is associated with a procoagulant state disrupting both primary and secondary hemostasis. Among other factors, elevation of von Willebrand factor levels with enhanced platelets function and increased factor X activity in the coagulation cascade have been described, all contributing to an elevated risk of coronary artery disease [13, 14]. In addition, the increase of thyroid hormones seem to be associated to coronary vascular degeneration and plaque instability [24]. In our case, this also justify to treat the limb ischemia in euthyroidism.

Thyroid hormones are also known to sensitize adrenergic receptors what enhances the vasoconstrictor effect of catecholamines on coronary arteries and hyperkinetic circulation, another possible cause of cardiac ischemia [16].

The clinical presentation and concomitant medications suggest AIT. However, the exact etiology of hyperthyroidism remains unclear and amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis is conceivable.

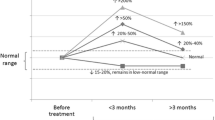

Given cardio-vascular complications related to hyperthyroidism, patients will primarily benefit from prompt treatment and restoration of euthyroidism [21]. Antithyroid drugs are the first-line treatment in this case, usually a combination of thionamides and glucocorticoids [4, 5]. Discontinuing amiodarone, which has a half-life of 100 days and acts as a T4 to T3 conversion inhibitor, is not recommended [2, 4, 5]. It will likely be ineffective and, even worse, might exacerbate the thyrotoxic state, potentially resulting in dangerous arrhythmias. Since medical treatment is expected to improve cardiac symptoms [12], additional cardiac investigations, such as a cardiac PET scan or a coronary angiography, should always be critically evaluated as they could potentially delay other critical interventions. A cardiac PET scan can suspect cardiac ischemia related for example to vasospasm in the coronary angiography, which can be resolved with appropriately treated hyperthyroidism [6,7,8, 11, 25]. However, a coronary angiography remains clearly indicated in case an acute myocardial infarction is suspected.

In line with the guidelines of the European Thyroid Association (ETA), a total or near-total thyroidectomy should then be considered for patients who do not respond to medical treatment for more than 2 weeks, exhibit a worsening cardiac status, or experience severe thyrotoxicosis requiring prompt resolution [20, 26]. In our case, rapid resolution of hyperthyroidism was necessary to perform endovascular limb revascularization.

Although anaesthetizing a patient with hyperthyroidism or AIT can be challenging, it doesn’t appear to be associated with increased intra- or peri-operative complications [17, 27,28,29]. However, one study described slightly elevated peri-operative morbidity and mortality [20]. Although patients are usually operated in euthyroid state, it has been shown in recent publications that patients with a mild to severe heart insufficiency for example will benefit from early thyroidectomy, in thyrotoxicosis when necessary [17,18,19,20]. This approach also appears reasonable, particularly when other critical operations are necessary, as in this clinical scenario a rapid endovascular revascularization. In our case, adopting a watchful-waiting strategy regarding the operation could have been associated to increased risk for complications, including exacerbation of limb ischemia.

Conclusions

Cardiac investigations with metabolic imaging (e.g., PET scan) in the context of AIT should not delay thyroidectomy especially when other crucial interventions are planned. A coronary angiography remains indicated in case of high suspicion of coronary stenosis or myocardial infarction. Thyroid surgery should be considered early in the treatment plan and patients might benefit from a simplified procedure.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting our findings were taken from the patient’s folder.

References

Vassallo P, Trohman RG. Prescribing amiodarone: an evidence-based review of clinical indications. JAMA. 2007;298:1312–22.

Martino E, Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Braverman LE. The effects of amiodarone on the thyroid*. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:240–54. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv.22.2.0427.

Daniels GH. Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1210/JCEM.86.1.7119.

Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Lai A, et al. Diagnosis and management of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis: similarities and differences between North American and European thyroidologists. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69:812–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03268.x.

Bartalena L, Wiersinga WM, Tanda ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis in Europe: results of an international survey among members of the European Thyroid Association. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61:494–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02119.x.

Ataallah B, Buttar B, Kaell A, et al. Coronary vasospasm-induced myocardial infarction: an uncommon presentation of unrecognized hyperthyroidism. J Med Cases. 2020;11:140–1. https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3473.

Choi YH, Jae HC, Sung WB, et al. Severe coronary artery spasm can be associated with hyperthyroidism. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:135–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019501-200505000-00001.

Kuang XH, Zhang SY. Hyperthyroidism-associated coronary spasm: a case of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with thyrotoxicosis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2011;8:258–9. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1263.2011.00258.

Malarkiewicz E, Dziamałek PA, Konsek SJ. Myocardial infarction as a first clinical manifestation of hyperthyroidism. Polish Ann Med. 2015;22:139–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poamed.2015.03.007.

Pereira N, Parisi A, Dec GW, et al. Myocardial stunning in hyperthyroidism. Clin Cardiol. 2000;23:298–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960230417.

Gowda RM, Khan IA, Soodini G, et al. Acute myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries associated with iatrogenic hyperthyroidism. Int J Cardiol. 2003;90:327–9.

Locker GJ, Kotzmann H, Frey B, et al. Factitious hyperthyroidism causing acute myocardial infarction. Thyroid. 1995;5:465–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.1995.5.465.

Homoncik M, Gessl A, Ferlitsch A, et al. Altered platelet plug formation in hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3006–12. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-2644.

Erem C. Blood coagulation, fibrinolytic activity and lipid profile in subclinical thyroid disease: subclinical hyperthyroidism increases plasma factor X activity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;64:323–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02464.x.

Dekkers OM, Horváth-Puhó E, Cannegieter SC, et al. Acute cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hyperthyroidism: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-16-0576.

Takasu N. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. Nippon rinsho. Japanese J Clin Med. 2006;64:2330–8.

Kaderli RM, Fahrner R, Christ ER, et al. Total thyroidectomy for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis in the hyperthyroid state. In: Experimental and clinical endocrinology and diabetes. Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2015. p. 45–8.

Cappellani D, Papini P, Pingitore A, et al. Comparison between total thyroidectomy and medical therapy for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:242–51. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz041.

Cappellani D, Papini P, Di Certo agostino M, et al. Duration of exposure to thyrotoxicosis increases mortality of compromised AIT patients: the role of early thyroidectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:E3427–36. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa464.

Kotwal A, Clark J, Lyden M, et al. Thyroidectomy for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis: Mayo Clinic experience. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2:1226–35. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2018-00259.

Quiroz-Aldave JE, Durand-Vásquez MC, Lobato-Jeri CJ, et al. Thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy: state of the art. Eur Endocrinol. 2023;19:78. https://doi.org/10.17925/ee.2023.19.1.78.

Oe K, Yamagata T, Mori K. Acute myocardial infarction following hormone replacement in hypothyroidism. Int Heart J. 2007;48:107–11. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.48.107.

Kassim TA, Clarke DD, Mai VQ, et al. Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:1137–49.

Beyer C, Plank F, Friedrich G, et al. Effects of hyperthyroidism on coronary artery disease: a computed tomography angiography study. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1327–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2017.07.002.

Lin TH, Su HM, Voon WC, et al. Unstable angina with normal coronary angiography in hyperthyroidism: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1607-551x(09)70273-6.

Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Chiovato L, et al. 2018 European Thyroid Association (ETA) guidelines for the management of amiodarone-associated thyroid dysfunction. Eur Thyroid J. 2018;7:55–66.

Gough J, Gough IR. Total thyroidectomy for amiodarone-associated thyrotoxicosis in patients with severe cardiac disease. World J Surg. 2006;30:1957–61.

Tomisti L, Materazzi G, Bartalena L, et al. Total thyroidectomy in patients with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3515–21. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1797.

Meerwein C, Vital D, Greutmann M, et al. Total thyroidectomy in patients with amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism: when does the risk of conservative treatment exceed the risk of surgery? HNO. 2014;62:100–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yoann Aubry was involved in patient’s diagnosis and treatment plan. Yoann Aubry and Michel Dosch were involved in the literature research and writing. Marc Donath was supervising and correcting the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The content of the manuscript has not been published, or been submitted for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aubry, Y., Dosch, M. & Donath, M.Y. Cardiac evaluation in amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction with suspected cardiac ischemia?: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 18, 235 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04552-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04552-w