Abstract

Background

Piriformis muscle mass is rare, which is particular for intrapiriformis lipoma. Thus far, only 11 cases of piriformis muscle mass have been reported in the English literature. Herein, we encountered one patient with intrapiriformis lipoma who was initially misdiagnosed.

Case presentation

The patient is a 50-year-old Chinese man. He complained of osphyalgia, right buttock pain, and radiating pain from the right buttock to the back of the right leg. Both ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a cyst-like mass in the right piriformis muscle. Ultrasonography-guided aspiration was performed on this patient first, but failed. He was then recommended to undergo mass resection and neurolysis of sciatic nerve. Surprisingly, final histology revealed the diagnosis of intrapiriformis lipoma. The patient exhibited significant relief of symptoms 3 days post-surgery.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of radicular pain are potentially challenging but necessary. Atypical lipoma is prone to be misdiagnosed, especially in rare sites. It is notable for clinicians to be aware of the presence of intrapiriformis lipoma to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Piriformis syndrome (PS), also known as sciatic nerve outlet syndrome, caused by compression of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle, is characterized by occasional sciatic-type pain, tingling, and numbness in the buttock along the sciatic nerve pathway down to the lower thigh and the calf [1]. The causes of PS are diversified, including inflammatory, traumatic, tumoral, and malformative factors [2, 3]. PS triggered by space-occupying lesions of the piriformis muscle is very rare. Up to date, only 11 cases of piriformis muscle mass have been reported in the English literature [4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Lipomas are one of the most common mesenchymal neoplasms and can occur in any region of the body that contains fat component, including the subcutaneous soft tissues, mediastinum, retroperitoneum, bones, or along the gastrointestinal tract [11]. Intrapiriformis lipoma is rare and the diagnosis might be intractable when presenting atypical. In addition, misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment, which causes unsatisfactory outcomes. Here, we present a case of a large intrapiriformis lipoma that was initially misdiagnosed, highlighting that clinicians should be aware that intrapiriformis lipoma might harbor atypical manifestations upon examination.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old Chinese man presented to the orthopedics department with chief complaints of osphyalgia, right buttock pain, and radiating pain from the right buttock to the back of the right leg. The right buttock pain was the most prominent symptom. The pain was accelerated by movement and relieved by lying supine, which induced abnormal walk in the patient. No previous relevant treatment or surgery was reported. Additionally, there was no significant relevant family or social history.

Lasegue’s sign and its strengthening test were positive. Physical examination also demonstrated the positive findings of right femoral nerve traction test and Faber test, and the limitation of right hip abduction was observed. Neurological examination of the lower limb did not demonstrate any loss of sensation or reduced muscle power in any of the nerve root distributions. Non-remarkable finding was revealed after the abdominal examination.

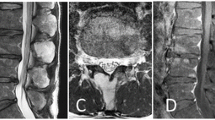

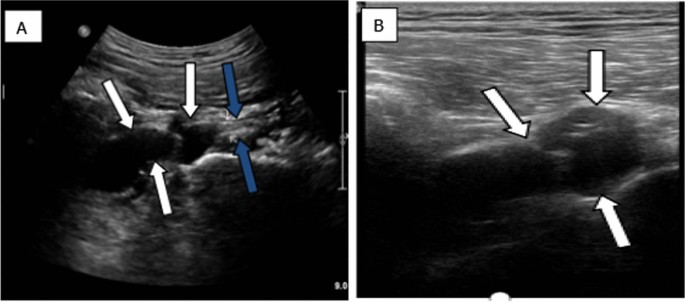

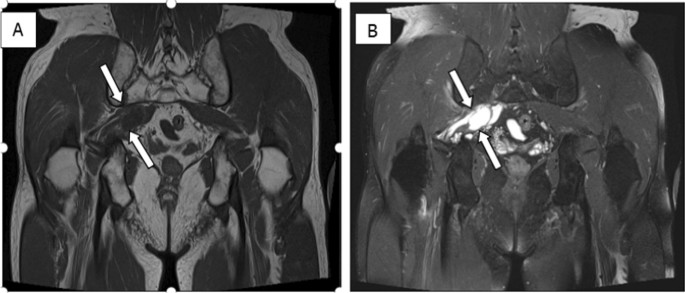

As no apparent abnormalities were indicated upon the plain radiograph imaging of his lumbar spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the lumbar/sacral area of the spine was then suggested, showing lumbar disc herniation (LDH), which did not account for the patient’s predominant right buttock pain. Thus, the musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSK-US) for the sciatic nerve scanning was performed, implying that the right sciatic nerve was pushed by an anechoic mass within the right piriformis muscle measuring 6 cm mediolateral, 2.3 cm anteroposterior, and 2.6 cm craniocaudal. The lobulated mass was cystic-like with regular margins and no posterior wall enhancement (Fig. 1). Subsequently, further MRI of the pelvis and ipsilateral hip indicated a cystic-like lesion in piriformis muscle region with low T1 signal and high T2 signal, and the maximum measurement was about 3.1 cm mediolateral and 2.2 cm anteroposterior (Fig. 2). Considering these results, a piriformis ganglion was suspected, and the differential diagnoses included hematoma, metastatic tumor, and so forth.

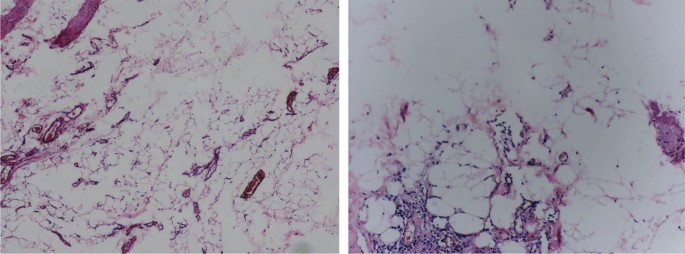

Aiming to achieve the final diagnosis, the ultrasonography-guided aspiration was conducted, but failed due to unextracted cystic fluid. In addition, significant resistance was encountered when injecting with physiological saline. As for the undefined nature of the mass and the associated serious symptoms, malignancy could not be excluded; the patient was suggested to undergo piriformis muscle mass resection and neurolysis of sciatic nerve. Operative finding showed the compression of right sciatic nerve by a fat-like mass at the lower margin of piriformis muscle measuring 5 cm mediolateral, 2 cm anteroposterior, and 2 cm craniocaudal. Final histology revealed that the lesion was fibrous adipose tissue, which was consistent with diagnosis of lipoma (Fig. 3). The patient exhibited significant relief of symptoms 3 days post-surgery. No recurrence of relevant symptoms was observed during 24-month follow-up period.

Discussion

Lower back pain can present with radicular pain caused by lumbosacral nerve root pathology. As a major cause of lower back pain, sciatica, and radicular leg pain, LDH is usually the first considered diagnosis. Similarly, in our case LDH was initially considered according to the MRI of the lumbar/sacral spine. However, the primary pain in the right buttock of this patient was unexplained on the diagnosis of LDH.

PS, also known as sciatic nerve outlet syndrome, is a type of sciatic neuralgia caused by compression of the piriformis muscle on the sciatic nerve. Typical manifestations include buttock pain and radiating pain in the innervated area of the sciatic nerve. In general, etiologies are composed of traumatic bleeding, adhesions, scars, anatomical variations, and so forth [2]. Of note, intrapiriformis lesion enlarging the muscle may be the common cause of sciatic nerve compression-induced secondary PS, whereas PS triggered by space-occupying lesions of the piriformis muscle is very rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 11 cases have been reported in the literature thus far; these patients and our present case are summarized in Table 1 [4,5,6,7,8,9,10], among which only 1 case of intramuscular lipomas occurring within the piriformis muscle leading to secondary PS have been previously reported in the literature [6].

Lipomas can be classified into superficial and deep lesions according to the location. Deep-seated lipomas are less common than superficial lipomas, which may be located under the muscle (submuscular), within the muscle (intramuscular), between the muscles (intermuscular), or on top of the muscle (supramuscular) [11]. Clinically, lipomas often present as asymptomatic slow-growing mass or swelling with no palpable mass. The application of ultrasound (US) in the examination of lipomas is very frequent. Usually, superficial lipomas might manifest as a hyperechoic solid mass without posterior acoustic enhancement or show as a isoechoic mass on gray-scale US. Compared with superficial lipomas, the deep-seated type can present as various US characteristics. In addition, few reports in the literature show the hypoechoic, isoechoic, or anechoic properties of deep ones [12,13,14]. However, the intrapiriformis lipoma in our case was featured as an anechoic lesion, usually indicated as cystic lesions. The MRI of the pelvis and ipsilateral hip showed the same signal characteristics as those of water on all sequences. Therefore, the lesion within piriformis muscle region was then misdiagnosed as ganglion and distinguished from neuschwannoma, liposarcoma, hematoma, lymphoma, metastatic tumor, and so on. Therefore, ultrasonography-guided aspiration was performed while noncystic fluid was extracted.

The echogenicity of lipomas may range from hyperechoic to anechoic, depending on the component percentage of connective tissue and other reflective interfaces presented within a lipoma [15]. It has been postulated that US and MRI appearance of lipomas are largely dependent on the internal cellularity, specifically on the proportion of fat and water within the lesion [16]. When the proportion of water in the lipoma is high, it may present the same imaging characteristics as this case.

Generally, intrapiriformis lipoma does not require treatment in the absence of symptoms, while for our case, considering the serious symptoms of this patient and undefined nature, even including malignancy, after series of examinations, surgical treatment was recommended. Fortunately, the patient showed significant relief of symptoms 3 days after surgery. No recurrence of associated symptoms was observed during 24-month follow-up period.

Conclusion

Despite the potentially significant challenges for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of radicular pain, it is highly necessary and essential. It is notable that medical practitioners should be aware of this condition and exclude space-occupying lesions of piriformis muscles when encountering patients presenting with radicular pain. Our case highlighted the atypical manifestations of lipomas in rare areas such as piriformis muscles, for which condition-adequate examinations should be performed and surgery might be finally suggested to reach the final diagnosis, thus avoiding misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment and increasing the life quality of these patients.

Availability of data and materials

The authors of this manuscript are willing to provide additional information regarding the case report.

Abbreviations

- MSK-US:

-

Musculoskeletal ultrasound

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PS:

-

Piriformis syndrome

- LDH:

-

Lumbar disc herniation

References

Hopayian K, Song F, Riera R, Sambandan S. The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2095–109.

Kirschner JS, Foye PM, Cole JL. Piriformis syndrome, diagnosis and treatment. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40(1):10–8.

Byrd JWT. Piriformis syndrome. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2005;13(1):71–9.

Salar O, Flockton H, Singh R, Reynolds J. Piriformis muscle metastasis from a rectal polyp. Case Rep. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007208.

Domínguez-Páez M, De Miguel-Pueyo LS, Medina-Imbroda JM, González-García L, Moreno-Ramírez V, Martín-Gallego A, et al. Sciatica secondary to extrapelvic endometriosis affecting the piriformis muscle. Case report. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2012;23(4):170–4.

Drampalos E, Sadiq M, Thompson T, Lomax A, Paul A. Intrapiriformis lipoma: an unusual cause of piriformis syndrome. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:551–4.

Park JH, Jeong HJ, Shin HK, Park SJ, Lee JH, Kim E. Piriformis ganglion: an uncommon cause of sciatica. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102(2):257–60.

Lodin J, Brušáková Š, Kachlík D, Sameš M, Humhej I. Acute piriformis syndrome mimicking cauda equina syndrome: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;2(17): CASE21252.

Sanuki N, Kodama S, Seta H, Sakai M, Watanabe H. Radiation therapy for malignant lumbosacral plexopathy: a case series. Cureus. 2022;14(1): e20939.

Ward TRW, Garala K, Dos Remedios I, Lim J. Piriformis syndrome as a result of intramuscular haematoma mimicking cauda equina effectively treated with piriformis tendon release. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2022;15(3): e247988.

Paunipagar BK, Griffith J, Rasalkar DD, Chow LTC, Kumta SM, Ahuja A. Ultrasound features of deep-seated lipomas. Insights Imaging. 2010;1(3):149–53.

Goldberg BB. Ultrasonic evaluation of superficial masses. J Clin Ultrasound. 1975;3(2):91–4.

Rahmani G, McCarthy P, Bergin D. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for soft tissue lipomas: a systematic review. Acta radiologica open. 2017;6(6):2058460117716704.

Fujioka K. A comparison between superficial and deep-seated lipomas on high-resolution ultrasonography: with RTE and MRI appearances. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2019;19:14220–4.

Behan M, Kazam E. The echographic characteristics of fatty tissues and tumors. Radiology. 1978;129(1):143–51.

Inampudi P, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP, Carlos RC, Patel SV, Delaney-Sathy LO, et al. Soft-tissue lipomas: accuracy of sonography in diagnosis with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 2004;233(3):763–7.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) gratefully acknowledge the useful suggestions given by Dr Ji-Bin Liu of Thomas Jefferson University, and the author(s) thank Xiaobo Luo for providing language assistance during article writing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Renmei Wu contributed to the collection of the medical history data. Xiao Qiu contributed to the manuscript preparation of this case report. Xiaoyong Luo supervised the case report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of Suining Central Hospital (no. LLSLH20220011).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, X., Luo, X. & Wu, R. Atypical lipoma of the right piriformis muscle: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 18, 189 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04507-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04507-1