Abstract

Introduction

In this case report, we demonstrate our technique of a retroperitoneal laparoscopic heminephrectomy for a T1b right hilar tumor in a horseshoe kidney.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old Vietnamese woman presented to the hospital because of right flank pain. On presentation, her serum creatinine was 0.86 mg/dL and glomerular filtration rate was 65.2 mL/minute/1.73 m2. According to her renal scintigraphy, glomerular filtration rates of the right and left moieties were 24.2 and 35.5 mL/minute, respectively. Computed tomography imaging demonstrated a 5.5 × 5.0 cm solid hilar mass with a cT1bN0M0 tumor stage was in the right moiety. After discussion, the patient elected a minimally invasive surgery to treat her malignancy. The patient was placed in a flank position. We used Gaur’s balloon technique to create the retroperitoneal working space, and four trocar ports were planned for operation. Three arteries were dissected, including two arteries feeding the right moiety, one artery feeding the isthmus, and one vein, which was clipped and divided by Hem-o-lok. The isthmusectomy was performed with an Endostapler. Consequently, the ureter was clipped and divided. Finally, the whole right segment of the horseshoe kidney was mobilized and taken out via the flank incision.

Results

The total operative time was 250 min with an estimated blood loss of 200 mL. The patient's serum creatinine after surgery was 1.08 mg/dL, and glomerular filtration rate was 49.47 mL/minute/1.73 m2. The patient was discharged on postoperative day #4 without complication. Final pathologic examination of the tumor specimen revealed a Fuhrman grade II clear cell renal cell carcinoma, capsular invasion, with negative surgical margins. After a three-month follow-up, the serum creatinine was 0.95 mg/dL, and glomerular filtration rate was 57.7 mL/minute/1.73 m2. Local recurrence or metastasis was not detected by follow-up computed tomography imaging.

Conclusions

Retroperitoneal laparoscopic heminephrectomy is a safe and feasible technique for patients with renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney and may be particularly useful in low income settings without access to robotic technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Horseshoe kidney is one of the most common renal fusion anomalies [1]. The anomaly is an ectopia of the two kidneys lying vertically on either side of the midline and connected to each other (98% in the lower pole) by the isthmus crossing the lumbar spine [2]. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for about one-half of renal tumors, although the incidence in patients with horseshoe kidneys has been found to be no greater than that in the general population [3]. Other tumors such as upper tract transitional cell carcinoma (UTTC), Wilms tumors, sarcomas, and carcinoids have also been reported [4,5,6,7]. Partial or radical nephrectomy is the gold standard in renal cell carcinoma treatment, but in horseshoe kidney, the standard surgical technique has not been defined due to the limited case numbers in the literature. Operations in horseshoe kidneys pose distinct surgical challenges due to their ectopic low-lying position and the often complex blood supply.

Herein, we report a case of a 77 year old Vietnamese woman diagnosed with a renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney treated by retroperitoneal laparoscopy heminephrectomy. There have been only a few case reports on laparoscopic heminephrectomy in horseshoe kidneys using a retroperitoneal approach [8, 9]. This case is presented in line with the Consensus Surgical Case Report (SCARE) guidelines [10].

Case presentation

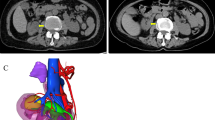

A 77-year-old Vietnamese woman presented to the hospital with right flank pain without fever or hematuria. On physical examination, the patient did not have a palpable flank mass or tenderness to palpation. Her vital signs were normal, and there was no evidence of paraneoplastic syndrome. The patient is considered healthy with no history of chronic medical disease or prior abdominal surgical operations. Her computed tomography (CT) showed a horseshoe kidney with a hilar tumor (55 × 50 mm) arising from the upper pole of the right moiety kidney with a RENAL score of 9p [11]. Additionally, the image revealed parenchyma fusion of the lower poles. A preoperative CT imaging is shown in Fig. 1. The computed tomography angiography showed two arteries feeding the right moiety and three arteries feeding the left moiety (Fig. 2). Each moiety had one large draining vein. On presentation, her serum creatinine was 0.86 mg/dL, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 65.2 mL/minute/1.73 m2. According to her scintigraphy, GFRs of the right segment and left segment of the horseshoe kidney were 35.5 mL/min and 24.2 mL/min, respectively. After consultation, the patient opted for laparoscopy retroperitoneal heminephrectomy in the right moiety tumor of the horseshoe kidney. The patient was considered at clinical T1bN0M0.

The patient was placed in a flank position. Initial access was obtained through a 1.5 cm incision below the tip of the twelfth rib. We used Gaur's balloon to create the retroperitoneal working space, and three more trocar ports were planned for operation. The port placement is shown in Fig. 3. Regarding the CO2 insufflation, we used a consistent pressure of 12 mmHg throughout the procedure. The kidney was retracted anteromedially, and we identified the horizontal psoas muscle as the key anatomic landmark. Three arteries were dissected, including two arteries feeding the right moiety, one artery feeding the isthmus, and one vein, which was clipped and divided by Hem-o-lok (Figs. 4, 5). The isthmus connected to the lower poles was exposed, and the isthmusectomy was performed with an Endostapler (Covidien Endo GIA 60 mm with Tri-staple Technology) (Fig. 6). Consequently, the ureter was clipped with a Hem-o-lok clip and divided. Finally, the whole right segment of the horseshoe kidney was mobilized. After the right segment of the horseshoe kidney was mobilized and freed from its attachments, it was carefully placed within a sterile, retrieval bag. This bag was then introduced through one of the laparoscopic ports, and the bag with the specimen inside was exteriorized through the 8 cm skin crease incision, which was created by widening one of the ports.

The total operative time was 250 min. The estimated blood loss for the heminephrectomy was 200 mL. Serum creatinine of the patient after surgery was 1.08 mg/dL and eGFR was 49.47 mL/minute/1.73 m2. The patient was discharged on postoperative day #4. Final pathologic examination of the tumor specimen revealed Fuhrman grade II clear cell renal cell carcinoma with negative surgical margins. After a three-month follow-up, the renal function was stable, with serum creatinine was 0.95 mg/dL, and eGFR was 57.7 mL/minute/1.73 m2, with a decrease of about 12% in renal function compared to the preoperative result. Local recurrence or metastasis was not detected by CT imaging at eight months follow-up.

Discussion

Horseshoe kidney is the most common congenital renal fusion anomaly [1]. Approximately 50% of horseshoe kidneys are asymptomatic. Common causes for symptomatic identification of horseshoe anomalies include infection, tumor, and calculus passage [12, 13]. Tumors in horseshoe kidneys have been reported with various pathologies, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC), transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), and nephroblastomas. However, the incidence of RCC in horseshoe kidneys is similar to that in normal populations [14, 15]. However, management of RCC in the horseshoe kidney population is extrapolated from the original guidelines with patients with normal kidneys. The size and locations of the renal mass as well as its proximity to the kidney unit sinus fat and pedicle as well its proximity to the isthmus are all factors to be considered in management of these masses. A heminephrectomy in a complex kidney mass of > 5 cm far from the isthmus can be managed with a heminephrecotomy. Depending on the surgeon's expertise, different approaches can be used to resect RCC: robotic, laparoscopic, or open; transperitoneal or retroperitoneal.

In this case, we elected for a retroperitoneal heminephrectomy approach rather than a transperitoneal approach. Radical heminephrectomy in horseshoe kidney poses an entirely new challenge when approached retroperitoneally, especially with the variable anatomy of the blood vessels, aberrant vasculature, and the presence of an isthmus [16,17,18,19]. The isthmus can be bulky parenchymatous or fibrous and usually has its own blood supply [20]. Blood supply may be atypical from 1 to 8 arteries supplying each or both kidneys [21]. Presurgical imaging to identify the renal vasculature is considered essential preoperatively [2]. Vascular blood supply cannot be easily predicted intraoperatively, and proper preoperative planning is vital to avoid vascular injury and decrease operative time.

The retroperitoneal approach was shown to have significantly less surgical and overall complications, shorter lengths of stay, and less drainage time but was associated with longer operative time in cases of minimally invasive partial nephrectomy [22]. Direct access to the vasculature and minimal mobilization of the kidney are two advantages of this approach. Preoperatively we identified two arteries on the right renal moiety (Fig. 1). This approach was a familiar one for the attending urologist and provided direct access to the vasculature and limited mobilization of kidney, which limit exposure and potential injury to other organs. During the operation, we identified the two arteries feeding the right moiety of the horseshoe kidney and one artery feeding the isthmus. All of the arteries were ligated and divided by Hem-o-lok (Weck® Hem-o-lok® Non-absorbable Polymer Locking Clips). Since the isthmus was small in this case, the endostapler (Covidien Endo GIA 60 mm with Tri-staple Technology) was enough to control the heminephrectomy kidney wound. The tumor was hilar arising from the upper moiety, and far from the isthmus, so the isthmus resection was oncologically safe. The final pathology results demonstrated a negative surgical margin.

Regarding blood supply to the isthmus, different techniques have been described in each report. The decision remains to either clip, clamp, or keep the blood supply to the isthmus prior to tumoral resection. In reality, no one size fits all, this decision on how to manage the isthmus has to be taken on a case-by-case basis and will depend on the thickness of the parenchyma at the isthmus, its vascular anatomy, and overall tumor location and characteristics. In addition, the use of ICG fluorescence in horseshoe kidney tumors has been described and may be helpful in cases of tumoral and vascular complexity, when vascular territories are unclear for selective clamping in cases of partial nephrectomy or isthmus preservation surgery [23].

The search for case reports of heminephrectomy for RCC in a horseshoe kidney was done between 1995 and 2022 (Summary in Table 1). Reports in non-English language were excluded. The table shows the laparoscopic heminephrectomy for horseshoe kidneys with renal cell carcinoma is safe and effective with the advantages of a minimally invasive surgery approach. However, the retroperitoneal laparoscopic approaches for heminephrectomy in a horseshoe kidney are still debated because all prior studies are limited by their small size, limiting the power of conclusions. Whether the type of surgical approaches influence the perioperative and oncological outcomes remains a controversial question and should be answered only within a comparative study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our case demonstrates that the retroperitoneal laparoscopic approach is a safe and viable option for managing complex clinical cases. This technique holds promise for healthcare settings in developing countries, where advanced robotic systems may not be readily available.

Availability of data

The data are available and can be provided upon reasonable request. Interested researchers may contact the corresponding author to gain access to the data.

References

Balawender K, Cisek A, Cisek E, Orkisz S. Anatomical and clinical aspects of horseshoe kidney: a review of the current literature. Int J Morphol. 2019;37:12–6.

Natsis K, Piagkou M, Skotsimara A, Protogerou V, Tsitouridis I, Skandalakis P. Horseshoe kidney: a review of anatomy and pathology. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(6):517–26.

Buntley D. Malignancy associated with horseshoe kidney. Urology. 1976;8(2):146–8.

Isobe H, Takashima H, Higashi N, et al. Primary carcinoid tumor in a horseshoe kidney. Int J Urol. 2000;7(5):184–8.

Santiago T, Clay MR, Azzato E, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of kidney involving a horseshoe kidney and harboring EGFR internal tandem duplication. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017; 64(11).

Murphy DM, Zincke H. Transitional cell carcinoma in the horseshoe kidney: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1982;54(5):484–5.

Nawaz G, Muhammad S, Jamil MI, et al. Neuroblastoma in horseshoe kidney. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2014;26(3):404–5.

Kitamura H, Tanaka T, Miyamoto D, Inomata H, Hatakeyama J. Retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy of a horseshoe kidney with renal-cell carcinoma. J Endourol. 2003;17(10):907–8.

Wei Y, Shen L, Ji Q, Zhu Q. Retroperitoneal robot-assisted single-port laparoscopic treatment of the horseshoe kidney with renal cell carcinoma: report of two cases. Asian J Surg. 2022;45(6):1267–9.

Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020;84:226–30.

Kutikov A, Uzzo RG. The RENAL nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol. 2009;182(3):844–53.

Kölln CP, Boatman DL, Schmidt JD, Flocks RH. Horseshoe kidney: a review of 105 patients. J Urol. 1972;107(2):203–4.

Pitts WR Jr, Muecke EC. Horseshoe kidneys: a 40-year experience. J Urol. 1975;113(6):743–6.

Dhillon J, Mohanty SK, Kim T, Sexton WJ, Powsang J, Spiess PE. Spectrum of renal pathology in adult patients with congenital renal anomalies-a series from a tertiary cancer center. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18(1):14–7.

Stimac G, Dimanovski J, Ruzic B, Spajic B, Kraus O. Tumors in kidney fusion anomalies–report of five cases and review of the literature. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38(6):485–9.

Benidir T, Coelho de Castilho TJ, Cherubini GR, de Almeida Luz M. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8(11–12):E918–20.

Qi X, Liu F, Zhang Q, Zhang D. Laparoscopic heminephrectomy of a horseshoe kidney with giant renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(5):2040–2.

Bhayani SB, Andriole GL. Pure laparoscopic radical heminephrectomy and partial isthmusectomy for renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney: case report and technical considerations. Urology. 2005;66(4):880.

Shao Z, Tan S, Yu X, Liu H, Jiang Y, Gao J. Laparoscopic nephron-sparing surgery for a tumor near the isthmus of a horseshoe kidney with a complicated blood supply. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(6):300060520926736.

Love L, Wasserman D. Massive unilateral non-functioning hydronephrosis in horseshoe kidney. Clin Radiol. 1975;26:409–15.

Khan A, Myatt A, Palit V, Biyani CS, Urol D. Laparoscopic heminephrectomy of a horseshoe kidney. JSLS. 2011;15(3):415–20.

Porpiglia F, Mari A, Amparore D, et al. Transperitoneal vs retroperitoneal minimally invasive partial nephrectomy: comparison of perioperative outcomes and functional follow-up in a large multi-institutional cohort (The RECORD 2 Project). Surg Endosc. 2021;35(8):4295–304.

Imai Y, Urabe F, Fukuokaya W, et al. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for the horseshoe kidney with indocyanine green fluorescence guidance under the modified supine position. IJU Case Rep. n/a(n/a).

Tobias-Machado M, Massulo-Aguiar MF, Forseto PH Jr, Juliano RV, Wroclawski ER. Laparoscopic left radical nephrectomy and hand-assisted isthmectomy of a horseshoe kidney with renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 2006;77(1):94–6.

Araki M, Link BA, Galati V, Wong C. Case report: hand-assisted laparoscopic radical heminephrectomy for renal-cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney. J Endourol. 2007;21(12):1485–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding has been received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XTN: Manuscript writing and editing. AE-A: Manuscript writing and editing. RWD: Manuscript reviewing and editing. HYT: Manuscript reviewing and editing. QTC: Manuscript editing. TTT: Manuscript editing. LQVD: Manuscript writing. MZ: Manuscript editing. NTL: Manuscript editing. HTTT: Manuscript editing. TST: Manuscript editing. MST: Project development, manuscript editing. Tuan Thanh Nguyen: Project development, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Regarding patient consent statement, the distribution of this publication was discussed and agreed upon as part of the preoperative consent.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ngo, X.T., El-Achkar, A., Dobbs, R.W. et al. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal heminephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma in horseshoe kidney: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 17, 512 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04274-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04274-5