Abstract

Background

Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma, also named Sternberg tumor, is a rare variant of uterine leiomyoma. The tumor is benign, but the appearance and growth pattern are unusual and alarming. In this article, we report a case of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma in a 55-year-old woman as well as review relevant literature.

Case presentation

We report a case of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma in a 55-year-old Iranian woman who presented with vaginal bleeding 4 months after menopause. Ultrasound showed two heterogeneous hypoechoic masses on the uterine fundus. Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed for the patient. Macroscopically, a large heterogeneous intramural mass (140 mm × 120 mm × 120 mm) with a grape-like exophytic mass on the fundus was observed. Her health status was good after surgery, and the patient was discharged from the hospital after 2 days. In a 1-year follow-up period, no recurrence or any other related complications were found.

Conclusion

It is important to recognize this rare variant of leiomyoma to prevent aggressive and inappropriate overdiagnosis and overtreatment. It is suggested to try to use frozen sections for better diagnosis and to preserve fertility in young women suffering from this lesion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Uterine leiomyomas have received great attention in recent years; however, the exact pathogenesis of uterine leiomyoma growth is not completely uncovered. Several agents such as growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, estrogen, progesterone, and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) are suggested to be involved in the growth of these tumors [1, 2]. Uterine leiomyomas might be found during an ultrasound examination; however, sometimes patients refer with abdominal pain and discomfort or pregnancy-related complications, including placental abruption, retained placenta, preterm labor, or postpartum hemorrhage [1, 3].

Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma, also known as Sternberg tumor, is a benign variant of leiomyoma with an unusual macroscopic appearance. It was reported for the first time in 1996 by Roth et al. [4]. Presently, only a few cases have been reported worldwide, in such a way that Jamal et al. call this tumor an uncommon form of a common disease [5]. The lesion usually shows an exophytic mass-like gross appearance of placental tissue and extends into the myometrium with dissection of myometrial fibers [6,7,8]. This gross appearance may mimic uterine malignancy [8, 9].

We report a case of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma in a 55-year-old postmenopausal woman who presented with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding and underwent total abdominal hysterectomy along with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This case report was written based on the reporting checklist for case report guidelines (CARE guidelines) [10], and written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. Moreover, this study was approved by Birjand University of Medical Science’s Research Ethics Committee (approval ID: IR.BUMS.REC.1401.119).

Case presentation

A 55-year-old Iranian woman with a history of two pregnancies and two deliveries presented with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, which began 4 months after menopause and lasted for 10 days. Laboratory tests showed moderate normochromic normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.8 g/dL, Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) 85 fl, Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) 27 pg, and Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC) 31.6 g/dL). On pelvic physical examination, a mass in the uterus was detected. The transabdominal ultrasound scan demonstrated two solid heterogeneous hypoechoic masses (141 mm × 110 mm and 81 mm × 61 mm) in the myometrium of the uterine fundus. No cystic lesion or mass was found in the adnexa. Hence, for evaluation of malignancy, the patient underwent an endometrial pipelle biopsy, which was normal. Finally, the patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and macroscopic and microscopic evaluations were performed.

Pathologic findings

Macroscopic

One tumoral tissue (140 mm × 120 mm × 120 mm) in the uterine fundus was found, originating from the myometrium, compressing the endometrial cavity. The tumor (measuring 35 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm) showed a multinodular appearance, which dissects the myometrium to the serosal surface and makes grape-like projections on the serosal surface of the uterine fundus (Fig. 1).

The boundary between the tumor and the myometrium was unclear. No necrosis was found in the tumor. One polypoid lesion (15 mm × 10 mm × 20 mm) in the endometrial cavity was also seen. Two separated small intramural leiomyomas (15 and 10 mm) were seen in the left uterus wall. No pathologic findings were seen in the bilateral adnexa.

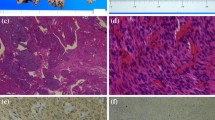

Histologic

The tumor showed multiple nodules composed of smooth muscle fibers arranged in fascicular and whorling structures. Cells showed eosinophilic cytoplasm and bland-looking plump nuclei. A significant stromal edema was seen. No necrosis was noted in the tumor. An intravascular growth was absent (Fig. 2). Mitotic activity was low (Ki-67 index < 5%) (Fig. 3). According to the above description, we came into the conclusion that the tumor was a cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma. An additional pathologic finding, in this case, was an endometrial polyp.

It should be noted that in 1-year follow-up period, no recurrence or any other related complications were found in the patient.

Discussion

Leiomyoma is the most common benign neoplasm of the female genital system. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma is a rare variant of leiomyoma with unusual macroscopic appearance, which may mimic malignancy due to its growth pattern in the uterus wall. This tumor was first reported in 1996 by Roth et al. [4]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma from Iran.

The age range of reported cases was 23–73 years [11]. Clinical presentations include abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic mass, constipation, bloating, and weight gain. However, the most common presentation is abnormal uterine bleeding, which was found in our case [11].

Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma has some variants:

-

1.

Some reported cases of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma had atypical cells; however, this microscopic finding cannot be diagnostic for malignancy without other criteria [12].

-

2.

A new form of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma named “cotyledonoid hydropic intravascular leiomyomatosis” is also described [13].

-

3.

Another variant called “cotyledonoid leiomyoma” was described by Roth and Reed, which is similar to cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma, but lacks an intramural component [14].

-

4.

Another author also described a variant called “intramural dissecting leiomyoma,” which lacks extrauterine placental-like component [15].

Disorganized smooth muscle fascicles as well as marked hydropic degeneration and extensive vascularity are the main key factors to diagnose cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma [16]. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma is a benign tumor, but its appearance is challenging for gynecologists, radiologists, and pathologists. Due to the unusual gross appearance of the tumor, one of the most important differential diagnoses is leiomyosarcoma. Classification of malignant smooth muscle tumors according to the study of Kempson and Hendrickson is based on tumor coagulation necrosis, mitotic activity (Ki-67 index), and cellular atypia [17]. According to the microscopic findings of our case (no necrosis, no cellular atypia, and low mitotic activity), leiomyosarcoma was excluded.

Table 1 provides a review of some cases of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma with their ages, clinical presentations, tumor size, and tumor location. Despite the macroscopic and microscopic unusual appearance of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma, no malignant behavior has been reported.

Conclusion

Although the microscopic or macroscopic appearance of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma might be malignant, no recurrence or aggressive behavior of this tumor has been reported until now. Therefore, the gynecologists, pathologists, and radiologists should be aware enough to recognize this rare variant of leiomyoma to prevent overtreatment. Although the gold standard treatment of this tumor in postmenopausal women is total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, it is important to preserve fertility in young women who suffer from this lesion. Therefore, it is suggested to try to use frozen sections for better diagnosis.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Chill HH, Karavani G, Rachmani T, Dior U, Tadmor O, Shushan A. Growth pattern of uterine leiomyoma along pregnancy. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):100.

Sarais V, Cermisoni GC, Schimberni M, Alteri A, Papaleo E, Somigliana E, et al. Human chorionic gonadotrophin as a possible mediator of leiomyoma growth during pregnancy: molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):2014.

De Vivo A, Mancuso A, Giacobbe A, Maggio Savasta L, De Dominici R, Dugo N, et al. Uterine myomas during pregnancy: a longitudinal sonographic study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(3):361–5.

Roth LM, Reed RJ, Sternberg WH. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus. The Sternberg tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(12):1455–61.

Jamal I, Gupta RK, Sinha RK, Bhadani PP. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma: an uncommon form of a common disease. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(5):362–6.

Buonomo F, Bussolaro S, Fiorillo CdA, Giorda G, Romano F, Biffi S, et al. The management of the cotyledonoid leiomyoma of the uterus: a narrative review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8521.

Fernandez K, Cheung L, Taddesse-Heath LJC. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma: a rare variant of leiomyoma of the uterus. Cureus. 2022;14(10): e30352.

Xu T, Wu S, Yang R, Zhao L, Sui M, Cui M, et al. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a report of four cases and a review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(4):2865–8.

Torres-Cepeda D, Rondon-Tapia M, Reyna-Villasmil E. Leiomioma disecante cotiledóneo del útero. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2022. https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v68i2392.

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Diet Suppl. 2013;10(4):381–90.

Smith CC, Gold MA, Wile G, Fadare O. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a review of clinical, pathological, and radiological features. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20(4):330–41.

Sonmez FC, Tosuner Z, Karasu AFG, Arıcı DS, Dansuk R. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma with symplastic features: case report. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39(8):436–40.

Jordan LB, Al-Nafussi A, Beattie G. Cotyledonoid hydropic intravenous leiomyomatosis: a new variant leiomyoma. Histopathology. 2002;40(3):245–52.

Roth LM, Reed RJ. Cotyledonoid leiomyoma of the uterus: report of a case. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19(3):272–5.

Roth LM, Reed RJ. Dissecting leiomyomas of the uterus other than cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyomas: a report of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(9):1032–9.

Ersöz S, Turgutalp H, Mungan S, Güvendı G, Güven S. Cotyledonoid leiomyoma of uterus: a case report. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2011;27(3):257–60.

Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Smooth muscle, endometrial stromal, and mixed Müllerian tumors of the uterus. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(3):328–42.

David MP, Homonnai TZ, Deligdish L, Loewenthal M. Grape-like leiomyomas of the uterus. Int Surg. 1975;60(4):238–9.

Brand AH, Scurry JP, Planner RS, Grant PT. Grape-like leiomyoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(3 Pt 1):959–61.

Kim MJ, Park YK, Cho JH. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17(6):840–4.

Cheuk W, Chan JK, Liu JY. Cotyledonoid leiomyoma: a benign uterine tumor with alarming gross appearance. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(2):210–3.

Stewart KA, Ireland-Jenkin K, Quinn M, Armes JE. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma. Pathology. 2003;35(2):177–9.

Saeed AS, Hanaa B, Faisal AS, Najla AM. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a case report of a benign uterine tumor with sarcoma-like gross appearance and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(3):262–7.

Maimoon S, Wilkinson A, Mahore S, Bothale K, Patrikar A. Cotyledonoid leiomyoma of the uterus. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49(2):289–91.

Shelekhova KV, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus with intravascular growth: report of two cases. Virchows Arch. 2007;450(1):119–21.

Gurbuz A, Karateke A, Kabaca C, Arik H, Bilgic R. A case of cotyledonoid leiomyoma and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(6):1218–21.

Weissferdt A, Maheshwari MB, Downey GP, Rollason TP, Ganesan R. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:18.

Raga F, Sanz-Cortés M, Casañ EM, Burgues O, Bonilla-Musoles F. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1269–70.

Driss M, Zhioua F, Doghri R, Mrad K, Dhouib R, Romdhane KB. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus associated with endosalpingiosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(6):1063–5.

Preda L, Rizzo S, Gorone MS, Fasani R, Maggioni A, Bellomi M. MRI features of cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus. Tumori. 2009;95(4):532–4.

Fukunaga M, Suzuki K, Hiruta N. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a report of four cases. APMIS. 2010;118(4):331–3.

Gezginç K, Yazici F, Selimoğlu R, Tavli L. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus with intravascular growth in postmenopausal woman: a case presentation. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16(6):701–4.

Agarwal R, Radhika AG, Malik R, Radhakrishnan G. Cotyledonoid leiomyoma and non-descent vaginal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(5):971–2.

Roth LM, Kirker JA, Insull M, Whittaker J. Recurrent cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32(2):215–20.

Tanaka H, Toriyabe K, Senda T, Sakakura Y, Yoshida K, Asakura T, et al. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma treated by laparoscopic surgery: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2013;6(2):122–5.

Onu DO, Fiorentino LM, Bunting MW. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma as a possible cause of chronic lower back pain. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-201350.

Kim NR, Park CY, Cho HY. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus with intravascular luminal growth: a case study. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47(5):477–80.

Blake EA, Cheng G, Post MD, Guntupalli S. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma with adipocytic differentiation: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2015;11:7–9.

Shimizu A, Tanaka H, Iwasaki S, Wakui Y, Ikeda H, Suzuki A. An unusual case of uterine cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma with adenomyosis. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11(1):69.

Lenz J, Chvátal R, Konečná P. Dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus with unusual clinical and pathological features. Ceska Gynekol. 2020;85(3):197–200.

Rocha AC, Oliveira M, Luís P, Nogueira M. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: an unexpected diagnosis after delivery. Acta Med Port. 2018;31(4):223–7.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed with the support of Birjand University of Medical Sciences (no. 5999).

Funding

This study was performed with the support of Birjand University of Medical Sciences (no. 5999).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AF, MC, and MA; methodology: AF, MC, and MA; formal analysis and investigation: AF, MC, MA, ARB, and FM; writing—original draft preparation: AF, MC, and ARB; writing—review and editing: AF, MC, MA, ARB, and FM; supervision: AF and MC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Birjand University of Medical Science’s Research Ethics Committee (approval ID: IR.BUMS.REC.1401.119). Moreover, the informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chahkandi, M., Ataei, M., Bina, A.R. et al. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 17, 516 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04271-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04271-8