Abstract

Background

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a parasitic zoonotic disease caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus. The liver and lungs are the most common sites for infection. Infection of the intradural spine is rare.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman of Han ethnicity presented with a chronic history of recurrent lumbar pain. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine revealed the classical characteristic of multiple cystic lesions of variable sizes, manifesting a “bunch of grapes” appearance, localized within the spinal canal at the L4–L5 vertebral level. In the meanwhile, metagenomic next-generation sequencing identified Echinococcosis granulosa. The patient underwent surgery to remove the cyst entirely and subsequently took albendazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 6 months.

Conclusion

Spinal CE should be suspected in patients with multiple spinal cystic lesions and zoonotic exposure. metagenomic next-generation sequencing serves as a robust diagnostic tool for atypical pathogens, particularly when conventional tests are inconclusive. Prompt and aggressive treatment for spinal cystic echinococcosis is imperative, and further research is warranted for improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a globally distributed parasitic zoonosis in humans caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus). The disease is a significant public health concern and endemic in various regions, particularly affecting pastoral and agricultural settings where close contact between humans and livestock is common [1]. While the liver and lungs are the most commonly affected organs, accounting for approximately 90% of all cases, spinal involvement is a rare manifestation of the disease. The scarcity of spinal CE cases makes diagnosis and treatment particularly challenging. In this case, we report a rare case of spinal cystic echinococcosis.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman of Han ethnicity presented to our emergency department with complaints of a 4-year history of recurrent lumbar pain and weakness in the right lower limb. The pain was related to the activity and relieved on lying down. She had no fever, night sweats, and weight loss. She was an agricultural worker with occupational exposure to wooded environments and had a documented history of canine interaction. In her past medical history, we noticed that she initially underwent a discectomy at the L4–L5 level 4 years prior, owing to persistent low back pain that was unresponsive to conservative measures. However, despite initial relief, she experienced symptom recurrence 2 years postoperatively. Subsequent imaging revealed a cystic lesion at the same spinal level, necessitating a second surgical intervention. Histopathological analysis of the resected tissue indicated chronic granulomatous inflammation but was inconclusive for specific pathogens. Regrettably, the patient’s lumbar pain recurred 8 months following the second procedure, prompting further diagnostic scrutiny.

The patient’s lower lumbar and sacral area was tender. She had reduced sensation in her left lower limbs at L5–S1 dermatomes. The straight leg raising test on the left leg was limited to 30°, and the right leg was 45°. Power grade and tendon reflexes in both lower limbs were normal. The complete blood count test and the C-reactive protein level were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed.

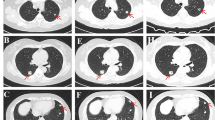

MRI showed that there were multiple cystic lesions of variable sizes in the spinal canal at the L4–L5 level, which appeared as a “bunch of grapes” [2] (Fig. 1). The cyst wall was enhanced in T1-weighted MRI with contrast medium and consistent low signal intensity in T2-weighted images. Cyst fluids showed water-like signals with low signal intensity in T1-weighted images and high signal intensity in T2-weighted images.

Magnetic resonance images of the lumbar spine. A Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing multiple low signal intensity lesions (red arrow). B Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with intravenous gadolinium contrast medium showing the same lesion with low signal intensity, but the edge is enhanced (red arrow). C Sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing multiple high signal lesions (red arrow)

Such radiographic findings prompted us to perform metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) on the previous tissue slices of surgery. The result confirmed the infection of Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus).

The patient underwent a PET/CT scan of the whole body to rule out potential CE cysts in another possible site of involvement [3]. No other extraspinal hydatid cysts were found. The patient underwent surgery to excise the cysts entirely and started walking again within 3 weeks. Subsequently, the patient was prescribed albendazole (400 mg orally twice daily) for 6 months. No recurrence was observed at 1-year follow-up after discharge.

Discussions

Our case report elucidates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with spinal CE, a rare but severe manifestation of Echinococcus granulosus infection. The patient’s occupational exposure to wooded areas and documented interaction with canines heightened the index of suspicion for a zoonotic etiology. Her recurrent lumbar pain, despite two prior surgical interventions, necessitated a more comprehensive diagnostic approach.

Often missed in clinical evaluations, CE, also known as hydatid diseases (HD), is a neglected parasitic zoonotic disease caused by the larval stage of E. granulosus [4] and found in canines (definitive host), sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs (intermediate hosts). CE is mainly endemic in agricultural and animal husbandry countries and rarely reported in other regions. Because the hydatid cyst grows slowly for several years, most patients remain asymptomatic during the initial phases of infection, thereby missing the optimal treatment stage. CE manifests as progressively enlarging space-occupying lesions in the liver, lungs, and other organs. The rupture of a cyst can lead to the spread of new cysts, inducing anaphylactic shock and potentially causing death [5]. The overall mortality rate of CE is around 2%, with an obvious increase in untreated or inadequately treated patients [6].

In previous studies, cystic lesions can be resided in any organ of the human body through blood. The liver (91.9%) [7, 8] is the most frequent site for cystic lesions in hydatid disease, followed by the lung and brain [9, 10]. Infection involving the spine is rare and only accounts for 0.2–1% of all cases [11].

The clinical manifestations of intradural spinal CE depended on the cyst’s location and size. It usually manifests as compression symptoms that cause back pain and neurological disability, which is also similar to other space-occupying lesions in the spinal canal and easily missed or misdiagnosed. Differential diagnoses of lesions located at the intradural spinal cord included schwannoma, metastasis, abscess, spinal tuberculosis, and parasites.

Traditional laboratory tests for echinococcosis include serological tests, X-rays, and MRIs. While serological tests offer some diagnostic utility, they are not invariably reliable. Radiographic techniques, including X-ray and MRI, can show the lesion site of most organs but are incapable of pathogen identification. In contrast, as a hypothesis-free, high-throughput sequencing technique, mNGS could detect a broad spectrum of nucleic acids in multiple specimens, such as blood, pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue specimens [12]. All pathogens in specimens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, can be detected without bias based on sequence information by comparing with established microbial sequence databases. Despite limitations such as high cost and the absence of standard interpretation of results, our case illustrates the invaluable role of mNGS in diagnosing unexplained, rare, and emerging infectious diseases when traditional laboratory tests fail [13].

The treatment of CE is based on surgical resection and drug treatment [14]. Surgery is the first choice for spinal CE, which should excise the CE cysts in full without rupture. Otherwise, cyst fluid can result in an anaphylactic reaction and a recurrence [14]. Albendazole (15 mg/kg/day) could help reduce the recurrence risk following surgery [15, 16]. In addition, regular follow-up with MRI is critical for patients. In this case, the patient recovered well and there was no recurrence after surgery and medication.

In summary, this case underscores the importance of considering spinal CE in the differential diagnosis of recurrent lumbar pain, especially in patients with relevant occupational or environmental exposures. Advanced diagnostic methods such as mNGS can be invaluable in complex cases, guiding clinicians toward appropriate and effective treatment strategies.

Conclusion

-

1.

In patients presenting with multiple spinal cystic lesions, spinal cystic echinococcosis should be considered, especially in patients with documented zoonotic exposure to canines or ovines.

-

2.

This case showed that mNGS could be a powerful tool for identifying uncommon pathogens in clinical specimens when results from routine tests are negative and the patient’s condition is undiagnosed. mNGS offers an innovative strategy for diagnosing neurological infections with nonspecific symptoms, thereby facilitating timely clinical decision-making.

-

3.

Spinal CE is an uncommon but serious manifestation of cystic echinococcosis that requires prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment. Further research is needed to understand the epidemiology and pathogenesis of spinal CE, as well as to develop more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- mNGS:

-

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CE:

-

Cystic echinococcosis

- HD:

-

Hydatid diseases

References

Serra E, Masu G, Chisu Chisu, et al. Environmental contamination by Echinococcus spp. eggs as a risk for human health in educational farms of Sardinia, Italy. Vet Sci. 2022;9:143.

Teke M, Göçmez C, Hamidi C, et al. Imaging features of cerebral and spinal cystic echinococcosis. Radiol Med. 2015;120:458–65.

Manenti G, Censi M, Pizzicannella G, et al. Vertebral hydatid cyst infection. A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:523–7.

Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, et al. Echinococcosis: advances in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00075–00018.

Surgical Management of Hydatid Disease. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/57205.

WHO/OIE Manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/929044522X.

Tao J, Du X, Liu K, et al. Clinical characteristics and antibodies against Echinococcus granulosus recombinant antigen P29 in patients with cystic echinococcosis in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:609.

Budke CM, Carabin H, Ndimubanzi PC, et al. A systematic review of the literature on cystic echinococcosis frequency worldwide and its associated clinical manifestations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:1011–27.

Craig PS, Hegglin D, Lightowlers MW, et al. Echinococcosis: control and prevention. Adv Parasitol. 2017;96:55–158.

Santivanez S, Garcia HH. Pulmonary cystic echinococcosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:257–61.

Zhang Z, Fan J, Dang Y, et al. Primary intramedullary hydatid cyst: A case report and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:107–10.

Chiu CY, Miller SA. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:341–55.

Ramachandran PS, Wilson MR. Metagenomics for neurological infections—expanding our imagination. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:547–56.

Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA, et al. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1–16.

Echinococcosis WIWGo. Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:231–42.

Neumayr A, Tamarozzi F, Goblirsch S, et al. Spinal cystic echinococcosis—a systematic analysis and review of the literature: Part 2 treatment, follow-up and outcome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e2458.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH, SL, XX, and CZ were involved in the care of the patient. XL wrote this manuscript. TL and TZ selected the clinical images. MC and LJ reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lao, X., Hu, D., Ji, L. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis in the intradural spine: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 466 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04197-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04197-1