Abstract

Background

Lupus nephritis and lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) are uncommon manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and their coexistence as the initial presentation of SLE is exceedingly rare. Here, we report such a case, emphasizing the diagnostic challenges and therapeutic implications of this unusual association.

Case report

A 38-year-old North African woman presented in Nephrology department with a history of lower extremity edema, fatigue, and weight loss of 3 kg in 4 weeks. Physical examination revealed LET lesions on the chest and the Neck. Laboratory investigations showed lymphopenia, low C3 and C4 complement levels, positive antinuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA antibodies, and anti-SSA/Ro antibodies. Renal function tests showed normal serum creatinine and nephrotic proteinuria. Renal biopsy revealed Class V lupus nephritis. Skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LET, with the presence of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates and dermal mucin. The patient was diagnosed with SLE based on the 2019 EULAR/ACR criteria and treated with prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) and hydroxychloroquine. She showed significant improvement in her cutaneous and renal symptoms at 6 and 12 months follow-up.

Conclusion

The rarity of the coexistence of LET and lupus nephritis as the initial manifestation of SLE, especially in the North African population, underscores the need for further research to elucidate the immunopathogenic mechanisms and prognostic factors associated with this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disorder that can present with diverse clinical manifestations, including cutaneous involvement and renal disease. However, lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET), a rare subtype of cutaneous lupus, is an unusual initial presentation of SLE, and lupus nephritis as the sole or predominant feature at onset is also infrequent.

Therefore, we present a remarkable case of a patient who was diagnosed with SLE based on the concurrent presence of membranous lupus nephritis and LET, without overt systemic symptoms.

Case report

A 38-year-old North African female patient was referred to Nephrology department with lower extremity edema for 1 month. She had a history of Primary hypothyroidism and secondary infertility with amenorrhea for a year. She reported asthenia and a weight loss of 3 kg in 1 month. She was apyretic. She had no arthralgias or myalgias. She did not suffer from oral or ocular dryness She did, instead, report the appearance of skin patches, which were photosensitive and showed fine scaling and associated pruritus.

On examination, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse was 99/min, temperature was 36.3 °C, and respiratory rate was 18/min. Urinalysis showed 2 + proteinuria and 1 + hematuria. The skin examination revealed firm curved erythematous patches on the neck, face, and chest and moderate edema of both lower limbs. There was no atrophy, scarring or dyspigmentation over the skin lesion (Figs. 1 and 2).

Initial laboratory investigations showed a decreased serum albumin level of 33.5 g/L then 28.2 g/l (normal rage: 35–50 g/L) and proteinuria of 4.5 g/day (urinary total volume 1000 mL). Microscopic examination of the urine showed microscopic hematuria (80–100 cells/HPF) and leukocyturia (50,000/mL). Electrophoresis of serum proteins showed a polyclonal peak in gamma globulins at 33.6 g/L. Serum creatinine was 58 μmol/L. The patient's blood test results showed a leukocyte count of 4900/mm3, with 1100/mm3 being lymphocytes, hemoglobin level of 12 g/dL, and a platelet count of 178,000/mm3. The patient's antibody test showed a positive result with a titer of 1:1800 and homogenous pattern. Additionally, the patient tested positive for anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies with a titer of 1:40, and for anti-Sm (+ +), anti-RNP (+ +), and anti-SSA antibodies (+). The complement C3 and C4 levels were reduced to 42 mg/L (normal range: 81–157 mg/dL) and 7 mg/dL (normal range: 13–39 mg/dL), respectively, while CH50 was 9.5 U/mL (normal range: 31.7–95 U/mL). The results for Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, Coombs' test, antiphospholipid antibody, serum cryoglobulins, serum and urine immunofixation electrophoresis, and anti-PLA2R antibody were all negative. The skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LET, with the presence of inflammatory lymphohistiocytic infiltrates and dermal mucin on and below the skin surface, with little or no involvement of the epidermis or dermo-epidermal layer (Fig. 3). Direct immunofluorescence of skin biopsy confirmed LET by the presence of CD3/CD4 lymphocytes.

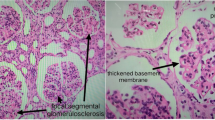

Ultrasound examination of the kidneys showed normal-sized kidneys (left 11.8 cm; right 11.7 cm). A renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy showed that 8/34 glomeruli were sclerotic and the rest showed segmental mesangial deposits and infiltration of neutrophils, but no mesangial cell or stromal proliferation. The glomerular basement membrane was diffusely thickened with segmental spikes. The renal interstitium contained some inflammatory infiltrates, and the tubules showed small focal atrophy and scattered proteinaceous and red blood cell casts. There was intimal fibrous proliferation and sclerosis of small arteries. Congo red stain for amyloid was negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed full-house staining along the mesangium and the capillary loops with subepithelial immune deposits of IgG (3 +), IgA (+), IgM (1 +), C3 (2 +), C1q (1 +), fibrinogen (2 +), albumin (−), kappa (2 +), lambda (3 +).

The patient met six of the EULAR/ACR 2019 classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [1], with a total score of 31 including glomerular proteinuria, and a Class V renal biopsy. Positive ANA results, positive anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies and reduced complement C3 and C4 proteins. Symptomatic treatment was based on anti ptoteinuric treatment with ACE inhibitors (Captopril 25 1 table × 2/day) and substantive treatment combined oral corticotherapy at 1 mg/kg/day (prednisone 5 12 tablets/day) for 1 month followed by tapering 5 mg/15 days and hydroxychloroquine 200 twice a day. No DMARD therapy for SLE has been initiated. After 1 month, the skin lesions regressed. At 6 and 12 months follow up, proteinuria improved to respecively 0.8 g/24 hour and 0.5 g/24 hour.

At the latest check-up, 22 months after the initial presentation, the patient’s proteinuria was 684 mg/24 hour, serum creatinine was 51 µmol/l, and there was complete resolution of the lesions.

Discussion

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a chronic skin inflammatory disease that was first reported in 1909 [2]. The coexistence of SLE and LET in the same patient, is extremely rare, seen only in 2–15% of cases in a retrospective case study [3]. The skin lesions of LET can be divided into two categories: those specific to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and those that are not [4]. The latter are considered a significant indicator of disease progression to the systemic form of lupus [5]. LET primarily affects sun-exposed areas and presents as erythematous, edematous, succulent plaques that are non-scarring [6, 7]. LET rash as seen in our patient, was usually highly photosensitive. Also usually there is no atrophy, scarring or dyspigmentation which is typically seen in other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus [8,9,10].

Some researchers consider LET to be a separate form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) given that, the incidence of LET is estimated to be 16% when considering all forms of cutaneous lupus [11]. The histopathological features of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) are characterized by perivascular lymphocytic infiltration and interstitial mucin deposition [12], with a notable absence of the typical features of acute CLE, such as interface dermatitis, epidermal involvement, and hair follicle alteration. In comparison to discoid lupus erythematosus, CLE tends to exhibit a more prominent mucin deposition, as observed in previous studies [7, 9, 13].

The progression to SLE has been reported in 12–18% of cases [11]. The relationship between SLE and LET is not fully understood and there have only been a few reported cases, primarily in Europe [9,10,11,12]. In a study of 40 patients diagnosed with LET, none of them showed evidence of systemic involvement or met the criteria for a diagnosis of SLE [8].

Our case is also unique because the patient is from North Africa, whereas most of the reported cases and series are from Europe, Asia, and America, and in relation to immunologic aspects, in majority of LET patients, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) is negative, ANA positivity is seen in less than 20% of patients [14,15,16]. The positivity of other commonly systemic lupus associated serologies such as dsDNA, SSA and SSB or low C3 and C4 complement levels are rarely seen in LET [17], making this case unique due to their presence. Anti-SSA and, sometimes, anti-SSB antibodies have been associated with photosensitivity in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, but this has not been seen in patients with LET [15,16,17]. In one Japanese series of ten patients with LET, four patients had an ANA titer of 1:160, four tested positive for anti-Ro/SS-A, and two tested positive for anti-La/SS-B [18]. Although systemic symptoms are not commonly observed in patients with LET, one case was reported to have developed systemic symptoms during the course of the disease, leading to a reconsideration of the diagnosis as early-stage SLE. LET has also been reported to occur during the course of Systemic Sclerosis [19].

Our case is as well significant because of the rare association between LET and severe SLE with lupus nephritis (NL). In our patient, the CH 50, C3 and C4 fractions of complement were lowered by consumption after the activation of the classical pathway observed in SLE, in particular with renal involvement.

Hydroxychloroquine sulfate has been shown to be effective in treating LET, with a daily dose of 6–6.5 mg/kg [20, 21]. Systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants may not be necessary, but were prescribed for our patient due to a concurrent diagnosis of lupus nephritis. Photoprotection is also important as LET is highly photosensitive [22].

This case underscores the importance of considering SLE in the differential diagnosis of patients with atypical skin lesions or unexplained renal dysfunction, even in the absence of classic signs or symptoms. Moreover, the coexistence of LET and lupus nephritis may reflect distinct immunopathogenic mechanisms and prognostic implications, warranting further investigation.

Conclusion

The uncommon occurrence of lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) as an initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), especially in conjunction with severe lupus nephritis, in our patient highlights the diagnostic challenges and clinical heterogeneity of SLE. Our report contributes to the expanding knowledge of the clinical spectrum of SLE, and emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach in the management of these complex cases.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Whittall Garcia LP, Gladman DD, Urowitz M, et al. New EULAR/ACR 2019 SLE classification criteria: defining ominosity in SLE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:767–74.

Hoffmann E. Demonstrationen: lupus erythematodes tumidus. Derm Zeitschr. 1909;16:159–60.

Choonhakarn C, Poonsriaram A, Chaivoramukul J. Lupus erythematosus tumidus. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(11):815.

Patsinakidis N, Kautz O, Gibbs BF, Raap U. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:707–19.

Filotico R, Mastrandrea V. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: clinico-pathologic correlation. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153(2):216–29. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0392-0488.18.05929-1.

Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P, Megahed M. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901–8.

Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(4):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.11206.

Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, Ruzicka T, Megahed M, Lehman P. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033–41.

Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupus érythémateux tumidus. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphil. 1930;37:1219–92.

Rockl H. Erythematodes tumidus; a case history with reference to the problem of erythematodic lymphocytoma. Hautarzt. 1954;5:422–3.

Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, Nyberg F. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the association with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort of 1088 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1335–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10272.x.

Jolly M, Laumann AE, Shea CR, Utset TO. Lupus erythematosus tumidus in systemic lupus erythematosus: novel association and possible role of early treatment in prevention of discoid lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13(1):64–9. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203304lu473cr.

Chen X, Wang S, Li L. A case report of lupus erythematosus tumidus converted from discoid lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(16):e0375. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010375.

Mond CB, Peterson MG, Rothfield NF. Correlation of anti-Ro antibody with photosensitivity rash in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:202–4.

Lee LA, Frank MB, McCubbin VR, Reichlein M. Autoantibodies of neonatal lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:963–9.

Sontheimer RD. Questions pertaining to the true frequencies with which anti-Ro/SSA autoantiboby and the HLA-DR3 phenotype occur in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:130–4.

Rodriguez-Caruncho C, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras MT, Roca J, Carrascosa JM, Ferrándiz C. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a clinical and histological study of 25 cases. Lupus. 2015;24(7):751–5.

Nishiyama M, Kanazawa N, Hiroi A, Furukawa F. Lupus erythematosus tumidus in Japan: a case report and a review of the literature. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(5):567–72. https://doi.org/10.3109/s10165-009-0192-y.

Logothetis CN, Konstantinov NK, Reyes MD, Emil NS, Tzamaloukas AH. Development of lupus erythematosus tumidus during the course of systemic sclerosis. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18064. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18064.

Chasset F, Bouaziz JD, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Francès C, Arnaud L. Efficacy and comparison of antimalarials in cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):188–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15312.

Chasset F, Francès C, Barete S, Amoura Z, Arnaud L. Influence of smoking on the efficacy of antimalarials in cutaneous lupus: a meta-analysis of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):634–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.025.

Patsinakidis N, Wenzel J, Landmann A, et al. Suppression of UV-induced damage by a liposomal sunscreen: a prospective, open-label study in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus and healthy controls. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(12):958–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12035.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Dr N. Litaiem active and thoughtful contribution to the management of the patient. We also thank Dr S. Rammeh for having performed and interpreted the patient skin biopsy.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH made substantial contributions to acquisition and interpretation of data and writing the manuscript. IG has been involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content. SB contributed through the patient’s management and providing of cutaneous lesions’ photos. NL made the specialized dermatological examination for our case. SR the examination of histopathological lesions in skin biopsy and providing the last photo. FBH, EA has given final approval for the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Published with written consent of the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hajji, M., Gorsane, I., Badrouchi, S. et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as lupus erythematosus tumidus and lupus nephritis: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 242 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-03981-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-03981-3