Abstract

Background

Tractional retinal detachment secondary to retinal vein occlusion is a complex entity that can be extremely difficult to manage due to an intricate association of the retinal tissue with the fibrovascular proliferation, making vitreous dissection an extraordinarily difficult procedure. Minimal surgery without endo-tamponade can reduce recovery time and avoid complications of surgery, which in some cases can lead to blindness and even phthisis.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old Indian woman presented with progressive worsening of vision (right eye) due to fovea involving tractional retinal detachment secondary to supero-temporal branch retinal vein occlusion. After anterior, core and peripheral vitrectomy, the epicenter of the fibrous bridge causing foveal split was identified and released. The corrected distance visual acuity improved from 6/60 pre-operatively to 6/12 post-operatively. At the 5-year follow-up, the patient remains stable both anatomically and visually.

Conclusions

This case illustrates how careful identification of the epicenter of traction helps maximize visual gain in patients with minimal risk of iatrogenic retinal tears and eliminates the need for endo-tamponade with either gas or silicone oil. Minimal surgery for tractional detachment provides excellent visual gains with minimal risks in select cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tractional retinal detachments secondary to retinal vein occlusion are an important cause of significant visual loss and require surgical management when the macula is involved or when there is extensive neovascularization and an impending vitreous bleed and/or chance of rhegmatogenous breaks [1, 2]. Pars plana vitrectomy with endo-tamponade is the treatment of choice, but the procedure is rendered difficult by extensive fibrovascular proliferation closely associated with and attached to the retina [3,4,5]. The situation is complicated by the presence in most cases of macular ischemia and generalized compromise of retinal function [5, 6]. Visual gains in such cases are extremely varied (between 20/40 and 20/400) [6], and largely poor given the ischemic nature of the disease and its complications, regardless of endo-tamponade use. Indeed, extensive surgery almost always necessitates the use of endo-tamponade.

The surgery itself can be complicated by iatrogenic retinal breaks and eventual total retinal detachment, leading to permanent loss of vision and even phthisis [5,6,7]. Here, we described a unique and interesting interesting case of how tractional retinal detachment with macular involvement secondary to retinal vein occlusion can be treated with minimal surgery, thereby avoiding the use of tamponades and subsequent complications, as well as ensuring early visual recovery.

Case presentation

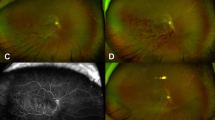

A 64-year-old Indian woman presented with progressive worsening of vision (right eye) due to fovea involving tractional retinal detachment secondary to superotemporal branch retinal vein occlusion. Her vision at presentation was 6/60 (logMAR 1.0) in the right eye and 6/6 (0.0 logMAR) in the left eye. Anterior segment examination revealed pseudophakia in both eyes. The intraocular pressure was 12 mm Hg in the right eye and 16 mm Hg in the left eye. She was diagnosed to have tractional retinal detachment (Fig. 1a) involving the macula in the right eye. The results of the left eye fundus examination were normal. She had a 10-year history of hypertension that was well-controlled on medication; otherwise, she had no clinically relevant family/social history. Given that the macula was involved in the tractional detachment, a decision was made to perform pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peeling and endolaser therapy with or without silicone oil (depending upon the finding of rhegmatogenous breaks, either pre-existing or iatrogenic, during surgery). The surgery was performed using the 23-gauge Constellation Vitrectomy System (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA). This gauge was chosen as there was a lack of stock of 25 G and 27 G sets in India at the time of surgery. Infusion was initiated at 7:00 a.m. through valved micro-cannulae. After anterior, core and peripheral vitrectomy, the epicenter of the fibrous bridge causing foveal split was identified and released using the vitreous cutter (Fig. 1b). The retina was observed by fall in place following this action. Further procedures could be avoided through proper identification of the epicenter of traction, and the use of intraocular gas/silicone oil was avoided. The eye was left with aqueous tamponade and examined the next day. The optical coherence tomography image showed that the retina had fallen back in place and it continued to re-attach over the following week. At 7 days postoperative, vision had improved to 6/12 (0.3 logMAR), and vision has beenen maintained over 5 years of follow-up. The postoperative B scan (Fig. 2) at the 5-year follow-up shows stable traction

Preoperative state: the tractional retinal detachment seen in a (clinical photograph) and c (OCT scan). This was largely relieved with transection of the epicenter of the fibrous band along the supero-temporal arcade (b; clinical photograph, yellow arrow) and d (OCT scan) after vitrectomy. The relief in traction has been stable over a 5-year follow-up, as evidenced by the fundus photograph (e) and OCT scan (f). The arrow points to cleavage in the fibrous band which helped settle the retina. OCT Optical coherence tomography

Preoperative ultrasound scans (a) of the patient demonstrates obvious traction adjacent to the disc (blue arrow). Ultrasound B scan at the 5-year follow-up shows that the traction remains relieved in the area adjacent to the disc (b). The patient’s vision recovered to 6/12 and has been maintained over 5 years. In the Ultrasound, the blue arrow points to the tractional detachment preoperatively and the yellow arrow points to the released traction postoperatively

Discussion and Conclusion

Tractional detachments associated with branch retinal vein occlusions are often considered to be among the most difficult to operate on [1,2,3,4], and minimal intervention to reattach the fovea should be the mainstay of treatment [5,6,7]. The primary challenge lies in the identification of a plane between the posterior hyaloid (so-called ‘second membrane’) and the retina [1, 4, 7, 8]. Non-identification of the membrane can lead to retinal breaks and convert a tractional retinal detachment into a combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, prompting a more thorough and more arduous clean-up of traction all over. This can be particularly difficult in an ischemic retina that tears readily at the slightest touch. The current general consensus in retinal surgery is one of minimum intervention, a change in strategy from the earlier adopted process of comprehensive removal of traction. The case presented here is an example of the latter approach. This case illustrates how careful identification of the epicenter of traction helps maximize visual gain in patients with minimal risk of iatrogenic retinal tears and eliminates the need for endo-tamponade with either gas or silicone oil. Endo-tamponades come with their own set of problems, such as lack of early visual rehabilitation, glaucoma, corneal decompensation and cataract formation. Complications for tractional detachment surgery has an incidence ranging from 3 o 20% [9, 10].

At the time of writing, the patient has been followed up for 5 years and, as seen in Fig. 1b, is stable both anatomically and visually. Past literature on minimalistic approaches for epiretinal membranes has been encouraging [11]. Reibaldi and associates reported similar visual acuity gains and improvements in retinal thickness in patients undergoing minimal surgery for retinal membranes when compared with patients who received standard vitrectomy. Indeed, the rates of nuclear cataract were significantly lower with the minimal approach, thereby improving patient quality of life. This is a solitary case report on a condition along the same spectrum but with a higher degree of traction, and further literature and similar case studies will buttress the perspective of minimal surgery.

In conclusion, minimal surgery for tractional retinal detachment secondary to retinal vein occlusion might be a good option in select cases wherein the primary problem is macular detachment in an otherwise stable eye.

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data is included in the manuscript.

References

Ikuno Y, Ikeda T, Sato Y, Tano Y. Tractional retinal detachment after branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):417–23.

Jalkh A, Takahashi M, Topilow HW. Prognostic value of vitreous findings in diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:432–4.

Ikuno Y, Ikeda T, Sato Y, Tano Y. Tractional retinal detachment after branch retinal vein occlusion. Influence of disc neovascularization on the outcome of vitreous surgery. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):417–23.

Russell S, Blodi C, Folk J. Vitrectomy for complicated retinal detachments secondary to branch retinal vein occlusions. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108(1):6–9.

Singh M, Dhir L, Kon C, Rassam S. Tractional retinal break and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment consequent to branch retinal vein occlusion. Eye. 2006;20:1326–7.

Margolis R, Singh RP, Kaiser PK. Branch retinal vein occlusion: clinical findings, natural history, and management. Compr Ophthalmol Update. 2006;7(6):265–76.

Weng H, Sung S-Y, Wang J-K. Rhegmatogenous or tractional retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage associated with branch retinal vein occlusion in a Taiwanese patient. Clin Res Ophthalmol. 2018;1(1):1–3.

Johnson TM, Vaughn CW, Glaser BM. Branch retinal vein occlusion associated with vitreoretinal traction. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(5):600–2.

Zheng CZ, Ren XJ, Ke YF, Wen DJ, Li XR. Minimally invasive vitrectomy for the treatment of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2021;57(6):440–6.

Sedova A, Steiner I, Matzenberger RP, et al. Comparison of safety and effectiveness between 23-gauge and 25-gauge vitrectomy surgery in common vitreoretinal diseases. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3): e0248164.

Reibaldi M, Longo A, Avitabile T, et al. Transconjunctival nonvitrectomizing vitreous surgery versus 25-gauge vitrectomy in patients with epiretinal membrane: a Prospective Randomized Study. Retina. 2015;35(5):873–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors state that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for Authorship. Authors AB and AS both conceptualized the manuscript and were involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in the final drafting and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The data presented in this article adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and subsequent ammendments.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

AB and AS have no financial disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bilgic, A., Sudhalkar, A. Minimal surgery for tractional retinal detachment secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion: a case report. J Med Case Reports 16, 285 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03496-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03496-3