Abstract

Background

Primary myelofibrosis is a rare myeloproliferative disorder in middle-aged and old adults and should be distinguished from secondary and reactive causes of bone marrow fibrosis because, in reactive fibrosis, treatment approaches depend on the underlying etiology.

Case presentation

Here we report the case of a middle-aged Iranian man who was diagnosed and treated as primary myelofibrosis at presentation, and whose final diagnosis was disseminated tuberculosis with reactive bone marrow fibrosis.

Conclusions

It is prudent to evaluate the potential causes of myelofibrosis in any patient with the diagnosis primary myelofibrosis. Tuberculosis can be an important etiology of bone marrow fibrosis, especially in endemic areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is an idiopathic, rare myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by clonal expansion of myeloid cells, bone marrow fibrosis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis [1]. PMF should be distinguished from secondary myelofibrosis, which is associated with some neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions, including myeloid and lymphoid hematologic disorders, autoimmune diseases, and infectious illnesses [2]. Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the potential etiologies for secondary myelofibrosis, and anti-TB medications can reverse this bone marrow fibrosis in many conditions [3,4,5]. In TB endemic regions, the possibility of disseminated tuberculosis should be considered in any patient with constitutional symptoms, organomegaly, and cytopenia [6]. Here we report the case of a middle-aged man with previous diagnosis of PMF that eventually was diagnosed as disseminated TB.

Case

A 46-year-old Iranian man from Kordestan, Iran, was admitted in Tehran Imam Khomeini hospital complex with complaints of weakness, significant weight loss, and dyspnea during recent 4 months.

He had a history of pancytopenia since 8 months ago, and a diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis was established from his bone marrow biopsy revealing fibrosis. His Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) mutation was negative. He was treated with low-dose prednisolone and danazol since 7 months ago.

His main complaints included anorexia, weight loss about 15 kg, fever, night sweats, and progressive nonproductive coughs during recent 4 months.

He was a smoker, about 20 pack-years, and did not have any previous comorbid diseases. His spleen was resected 4 years ago after an abdominal trauma.

On physical examination he was conscious, ill, and cachectic. Oral temperature was 38.4 °C, and respiratory rate was 22 breaths/minute. He had coarse crackle in lungs. No peripheral lymphadenopathy was detected, but the liver was palpable. Laboratory data revealed pancytopenia, elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) (Table 1). Viral markers for hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. His purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was negative. His sputum smear for mycobacterium was also negative.

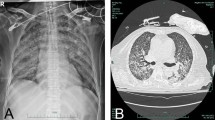

On chest computed tomography (CT) scan, diffuse ground-glass opacity of both lungs was seen with centriacinar nodules in upper lobes and bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 1)

Abdominopelvic CT revealed enlarged liver and accessory spleen, hypodense infiltrative lesions in both kidneys, multiple paraaortic lymph nodes (up to 12 mm), and severe ascites. Lytic destructive lesions in thoracic vertebra 11 (T11) and T12 were also detected (Fig. 2).

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed; the aspiration was dry tap, and biopsy showed multiple focal fibrosis and aggregation of epithelioid histiocytes forming granuloma. Reticulin staining revealed marked fibrosis in marrow spaces particularly around granuloma (Fig. 3). Percutaneous liver lesion biopsy was also performed, which indicated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 4).

A, B Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining ×100. Liver tissue with multiple epithelioid granulomatous nodules of varying sizes, some with Langhans type giant cells. C Hematoxylin and eosin staining (×400). Central necrosis indicative of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation

The patient history and findings of CT scans and tissue biopsies were in favor of disseminated tuberculosis. Therefore, anti-mycobacterium therapy was started including isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide.

Our patient’s dyspnea and appetite improved over the next 10 days. His blood counts increased, and he was discharged after 2 weeks with white blood count (WBC) of 2.9 (103/μL), hemoglobin (Hb) of 10 (gr/dl), and platelet of 140 (103/μL). His final diagnosis was disseminated tuberculosis with secondary myelofibrosis. The anti-TB medications was continued. In follow-up visits after 2 months, his overall clinical status was improved, with 5-kg weight gain and no fever. His blood counts were near normal, including WBC of 3.9 (103/μL), Hb of 12 (gr/dl), and platelet of 177 (103/μL). Anti-TB medications were continued thereafter.

Discussion

PMF is the least frequent myeloproliferative disease, characterized by bone marrow fibrosis, cytopenia, constitutional symptoms, organomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Diagnosis of PMF requires demonstration of myeloproliferative mutational markers such as JAK2 or CALR mutation and evaluation of potential causes of secondary myelofibrosis, including infection, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory disorders, malignancies, and toxic agents [2].

Tuberculosis is one of the reported etiologies of myelofibrosis. Verma and his colleagues found that increased interleukin 1 (IL1) secretion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis can activate fibroblasts and induce marrow fibrosis [7]. Our patient’s JAK2 mutation was negative at time of diagnosis, and there was no evidence of clonal disorders. He was almost young for PMF as the median age of PMF is 67 years [1, 2]. He denied any previous TB exposure, and his PPD and sputum cultures were negative, which may be seen in disseminated TB [3] and can make the final diagnosis more challenging.

The most common extrapulmonary sites of TB involvement include lymphatic system, bone, joints, liver, central nervous system, and adrenal glands. In patients with the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection, pancytopenia should raise a concern for disseminated tuberculosis and can be a manifestation of bone marrow infiltration [2, 3]. In our patient, bone marrow extrapulmonary findings were the initial presentation of his disease, and eventually his multiple organs were involved, including liver, lymph nodes, and lungs. His alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin were elevated with cholestatic pattern because of multiple tuberculosis granulomatous lesions as he did not have any preexisting liver diseases. We started anti-TB medications without any modifications because his impaired liver function associated to TB. The liver impairment was not related to any medications or previous liver diseases [8].

In the cases of bone marrow TB, the mortality rate is as high as 50% to near 100%. Some risk factors for poor outcome include: disease severity, immunocompromised state, and delay in starting medication. Our patient had almost all poor prognostic factors, but after initiating anti-TB medications, both clinical and laboratory findings improved very well. His liver enzymes and blood counts got close to normal ranges, consistent with treatable reversible myelofibrosis [3, 4].

Conclusion

It is essential to evaluate the potential underlying causes of myelofibrosis in any patient with the diagnosis of PMF. Tuberculosis is one of the important causes of myelofibrosis, especially in endemic regions of developing countries.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- CRP:

-

C- reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- GMS:

-

Grocott’s methenamine silver

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- JAK2:

-

Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- PMF:

-

Primary myelofibrosis

- PPD:

-

Purified protein derivative

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid Schiff

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WBC:

-

White blood count

References

Komrokji R, Kuykedall A, Padron E, Verstovsek S. Myelofibrosis. Wintrobe’s Clinical Hematology 14th ed; 84: 1.

Tefferi A. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis. Uptodate 2018.10.8.

Sharma N, Bikkina S, Gupta M, Tahlan A. Myelofibrosis: an unusual presentation of disseminated tuberculosis. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2020;9:2.

Viallard J, Parrens M, Boiron J, et al. Reversible myelofibrosis induced by tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1641–3.

Panda A, Chandrashekhara H, Nambirajan A, Mishra P. Idiopathic myelofibrosis with disseminated hepatosplenic, mesenteric, renal and pulmonary extra-medullary hematopoiesis, portal hypertension and tuberculosis: initial presentation and two year follow up. BMJ Case Rep 2016

Ish P, Dhar J, Khadelwal L, Singh H. Tuberculosis causing reversible myelofibrosis. Astrocyte 2018: 1–4

Verma SC, Agarwal P, Krishnam MY. Primary mouth lung fibroblasts help macrophages to tackle Mycobacterium tuberculosis more efficiently and differentiate into myofibroblasts up on bacterial stimulation. Tuberculosis. 2016;97:172–80.

Chan KS. Treatment of tuberculosis in presence of hepatic and renal impairment. Respirology. 2008;13(3):100–7.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of our following colleagues in diagnosis and treatment of our patient: Dr. Farid Azmoudeh Ardalan, Dr. Ali Dehghan, and Dr. Seyed Reza Safayi.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK: pulmonologist, Shahid Beheshti University of medical science, email: mef_kh@yahoo.com. MG: hematologist and medical oncologist, Iran University of medical science; Corresponding author, email: dr.ghalam@yahoo.com. FA: pathologist, Tehran University of medical science, email: fereshtehameli@gmail.com. HY: Master of Public Health, Emory University, email: Habibeh.yekehtaz@emory.edu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that this manuscript conducted with ethical approval of the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest exists.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khatuni, M., Ghalamkari, M., Ameli, F. et al. Disseminated tuberculosis with myelofibrosis presentation: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15, 550 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03038-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03038-3