Abstract

Background

Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome is a rare disease affecting mainly children and young women. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion. Studies report recent infections or certain drugs as precipitating factors of a lymphocytic oculorenal immune response. The prognosis is usually favorable with topical and systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Case presentation

We report a literature review and the case of a 14-year-old white girl, who presented to the ophthalmology department with features of one-sided uveitis. Upon transfer of patient to nephrological care, diagnostic work-up revealed renal involvement. Renal biopsy showed a mixed-cell and granulomatous tubulointerstitial nephritis with some noncaseating granulomas, leading to a diagnosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome. With topical ocular and systemic corticosteroid therapy, the patients’ condition improved over several weeks.

Conclusions

Our case highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment of this syndrome, where cross-specialty care typically leads to a favorable outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is a rare multisystem autoimmune disorder, presenting mainly with oculorenal pathology. Since its first recognition by Dobrin et al. [1], more than 300 cases have been reported worldwide [2]. Here we present the case of a 14-year-old girl who presented to our department with unilateral anterior uveitis and concomitant signs of acute interstitial nephritis. Upon extensive work-up, the diagnosis of TINU syndrome was confirmed.

The case is worth to be presented as it showed elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate with only mild urine and biochemical abnormalities, but important histological changes on renal biopsy. Also, a review of published case series is provided.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old white girl with unilateral anterior uveitis and abnormal urinalysis was referred from the ophthalmological care to our nephrology unit in November 2018. She had been seen at our out-patient clinic at the age of 12 years in 2016. Her family history was positive for elevated blood pressure. She was the first child of an uneventful pregnancy, born at 40 weeks gestation with a birth weight of 3990 g and birth length of 53 cm.

Upon visit, she was seen due to elevated blood pressure with occasional tension-type headaches, obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, and hyperlipidemia, which were a result of a sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy eating habits. She reported no first-degree family members with metabolic syndrome or its complications. Ambulatory blood pressure monitor values were within reference ranges (average 24-hour systolic and diastolic blood pressure 117 and 66 mmHg, respectively), so we implemented nonpharmacological lifestyle approaches. During follow-up, she received extensive evaluation, including endocrinological and dietary assessment, and was continued to be seen by our pediatric nephrologist twice per year.

In October 2018, aged 14 years, she presented to the Department of Ophthalmology with 1 week of redness, pain, epiphora, and loss of visual acuity of the right eye. She denied any recent drug exposure, allergy, infection, or symptoms of systemic illness. A diagnosis of acute anterior uveitis was made, followed by topical corticosteroid and cycloplegic treatment, which led to symptom alleviation.

Investigations

A broad diagnostic work-up was performed. Renal ultrasound was normal. Also, chest radiography was also normal (Fig. 1), which in conjunction with a normal serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level and absence of cough excluded sarcoidosis, a known oculorenal offender. However, upon laboratory evaluation, marked elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, 98 mm/hour), mild elevation of serum C-reactive protein (CRP, 13 mg/L), mild normocytic anemia (Hb, 113 g/L), elevated serum creatinine (80 µmol/L), mild proteinuria (0.38 g/day), microalbuminuria (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, 58 mg/g), elevated values of alpha-1 microglobulin (urine alpha-1-microglobulin-to-creatinine ratio, 3.24 mg/g), and normoglycemic glycosuria (1+) were observed. Immunological screening revealed elevated C3 complement fraction (C3, 2.01 g/L), with negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-extractable nuclear antigen antibodies (ENA), anti-deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies (anti-DNA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) antibodies. These values indicated mild renal involvement and prompted a referral to our nephrology unit.

Upon admission, she had no history of unexplained fevers, weight-loss, or other systemic symptoms. She had a pulse of 100 beats/minute, blood pressure of 126/81 mmHg, and body temperature of 36.5 °C. Her review of systems was negative, with a gradual improvement of symptoms and vision of the right eye. She continued both-sided topical cycloplegic and topical corticosteroid therapy. Borderline blood pressure values with repeated and persistent abnormal values of ESR, serum urea and creatinine, proteinuria, and glucosuria, indicating kidney injury, prompted a kidney biopsy.

Histopathology revealed focal tubulointerstitial nephritis. Interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate was composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, fewer neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells and rare noncaseating granulomata, with foci of invasion of lymphocytes into the tubules (tubulitis). Tubules in the affected areas showed signs of acute tubular injury—flattened, irregular, and vacuolated tubular epithelium. Glomeruli and vessels were unremarkable (Figs. 2, 3). Immunofluorescence was negative. Electron microscopy showed no specific pathological findings. On the day of renal biopsy, 1 month after first symptom presentation, she also developed contralateral, left-sided anterior uveitis. A diagnosis of TINU syndrome was confirmed, based upon histopathological findings.

DNA typing of HLA loci showed the subtype HLA-B *07, *51; DRB1 *11, *13; DQA1 *05:05/05:09; DQB1 *03:01, negative for uveitis-related HLA-B27 genotype. Next-generation sequencing did not demonstrate any disease-related variants.

Treatment

The patient was started on methylprednisolone 60 mg daily, which improved the laboratory markers of kidney injury and allowed us to continue an alternate-day corticosteroid therapy regimen. She also received pantoprazole 40 mg daily, trimetoprim–sulfametoxazole 480 mg twice daily every other day for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prevention, and vitamin D supplementation 2000 units daily, together with topical ocular therapy (scopolamine, nepafenac, dexamethasone). Because of elevated blood-pressure readings, she began therapy with ramipril 2.5 mg and later 5 mg daily and received regular follow-up.

Outcome and follow-up

After 3 months, upon evaluation at our out-patient clinic, her ocular symptoms improved, although she started having pain in her lumbar spine. Clinical examination showed a Cushingoid appearance with a 4 kg increase in body weight since discharge. Blood pressure values with antihypertensive therapy were normal. Lumbosacral spine X-ray imaging was normal, without signs of osteopenia (Fig. 4). This allowed a slow reduction in corticosteroid therapy upon following weeks and motivated her for implementation of healthy lifestyle measures.

At the most recent ambulatory office visit, two and a half years after onset of TINU, the patient denied any further ocular exacerbations, but she gained weight and had a body mass index of almost 35 kg/m2. Her 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure values were normal, as well as renal ultrasound examination, without presence of renal scarring. She was receiving ramipril 2.5 mg and metformin 500 mg twice daily each, together with education on necessary lifestyle changes.

Discussion and conclusions

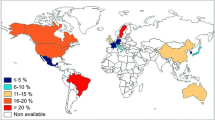

Our article presents, to the best of our knowledge, the first Slovene case of TINU syndrome in a 14-year-old girl in published literature. The diagnosis was suspected by the presence of renal and ocular findings, combining acute interstitial nephritis and anterior uveitis, and confirmed by renal biopsy. Current literature suggests that approximately 300 cases have been published [2]. We present a literature review of 580 described cases. Table 1 presents the case series published in the last 10 years. Countries with published case series are presented in Fig. 5 and in greater detail in Table 2.

Pathophysiology

In 2001, Mandeville et al. [3] proposed diagnostic criteria for TINU syndrome, comprising clinical and histopathologic features. Since then, studies have tried to elucidate the underlying mechanism of disease. Limited data suggest that modified C-reactive protein (mCRP), a uveal and renal tubular autoantigen, might play a role in eliciting an IgG-mediated oculorenal immune response [4]. A novel human glycoprotein, Krebs von den Lungen-6, was also observed to be significantly increased in sera and distal renal tubules of TINU patients [5]. Furthermore, certain interleukin-10 polymorphisms have been found to be more prevalent in TIN/TINU patients, broadening our understanding of the genetic basis of the disease [6].

Differential diagnosis and epidemiology

TINU syndrome was shown to represent 15–65% of cases of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) in pediatric renal care centers [7, 8]. It is essential to distinguish it from other causes of AIN, either drug-induced, autoimmune, metabolic, malignant, or consequential to a variety of infectious causes [9,10,11].

A large case series [3] suggests TINU shows a 3:1 female-to-male predominance, with a median age of 15 years. A UK-based study estimated the incidence as 1 per 10 million population per year [12]. Several recent reviews confirmed peak incidence in adolescence and a female-to-male predominance [9, 13,14,15,16]. Genetic studies indicate a strong association with certain HLA haplotypes, especially variants DQA1, DQB1, DRB1, and DR14 [17,18,19,20,21]. No disease-associated HLA variants were confirmed in our patient.

Clinical presentation

TINU patients typically present with a viral-like illness, after which renal dysfunction is discovered. Alternatively, in about 20% of cases (including this case), the patient presents with symptoms of burning eyes and/or visual blurring [9, 13,14,15,16] and is subsequently discovered to have renal manifestations. This asynchrony prompts a high degree of clinical suspicion in treating young, female patients with AIN or acute uveitis. In a Finnish study [2], which prospectively evaluated the presence of acute uveitis in biopsy-proven AIN at onset, at 3 and at 6 months afterwards, 16/19 (84%) of pediatric patients had uveitis within the observation period, half (8/16) without ocular symptoms. However, there are no guidelines or recommendations regarding ocular screening in patients with AIN.

Acute kidney injury is nearly universal in the setting of TINU and is usually in the mild-to-moderate range. It may be complicated with hypertension, which was also the case in our patient. In literature, cases of Fanconi syndrome and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in association with TINU have been described [23, 24], as well as progression to chronic kidney disease in adult and pediatric patients [25]. Table 3 presents TINU characteristics in comparison with disease manifestations, seen in our patient.

Pathohistological findings

Upon light microscopy, features of a predominantly CD3-positive lymphocytic infiltrate with fewer plasma cells and macrophages are present. A prominent eosinophilic infiltrate may be seen initially, as well as interstitial granulomas that can become confluent. Upon disease progression, the inflammation subdues, while variable amounts of interstitial fibrosis appear. The CD4-to-CD8 ratio varies. However, studies indicate a reciprocal T-cell profile in the kidney as compared with what is seen in peripheral blood, indicating that cellular immunity is active at the tissue level and decreased systemically [9]. Tubular atrophy or tubulitis is also characteristic for TINU and is in accordance with clinical evidence of tubular dysfunction, reported in our patient and many cases of TINU [9, 26].

Treatment

As in other uncommon disorders, there are no evidence-based treatment protocols, so the decision whether to initiate systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy depends on renal and ocular involvement. If nephritis is mild or in remission, topical steroids may be used to treat uveitis, though not efficient in posterior intraocular segment involvement [9]. Systemic corticosteroids are generally reserved for cases of progressive renal involvement [3] and are needed in about 80% of patients [27]. Oral prednisone or prednisolone with a dosage of 1–1.5 mg/kg/day is usually used. The duration and schedule for tapering of steroid dose depends mainly on patient response [9, 13, 15, 16, 27]. Because of frequent relapses and recurrences of disease, some authors suggest at least 12 months of oral corticosteroid therapy [28], while others advocate an early and short course [29], which was the case in our patient. We believe that, in the absence of evidence-based treatment protocols, a case-by-case management may be adopted [27].

In a pediatric case series [2], all 16 patients with TINU received topical ocular steroids. Mydriatic therapy was necessitated in 9/16 patients and antiglaucoma therapy in 6/16 cases. Surprisingly, oral prednisone did not influence occurrence of uveitis. In steroid-resistant cases or in exacerbation of disease after weaning from corticosteroid therapy, immunosuppressive medications such as cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil may be used [9, 13, 15, 16].

Prognosis

Ocular and renal outcomes are usually good with appropriate treatment, as most respond to initial topical or systemic therapy. The disease may remit altogether or run a chronic or recurrent course, usually appropriately controlled through judicious use of immunosuppressive agents [9, 20, 30]. Though early TINU literature held that renal disease often resolved spontaneously, repeat renal biopsy studies reported cases of continued nephritis after pulse corticosteroids [31, 32], mandating close follow-up of patients for several years after disease onset. Prompt corticosteroid therapy initiation also seems to play a role as demonstrated in a small case series, where a patient with delayed treatment demonstrated persistent elevations of beta-2-microglobulin and renal inflammation with subsequent renal damage [33]. Additionally, severe TINU can lead to end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis and kidney transplant [16].

Most patients will maintain or improve eyesight from presentation. However, ocular disease recurs in up to 50% of patients after corticosteroid withdrawal [16]. Younger age was identified as a risk factor for chronic uveitis, though few studies have evaluated the impact of systemic therapy on reducing that risk [16]. Vision is seldom severely impaired, as demonstrated in a case series of 133 patients [3], where vision outcome was rarely worse that 20/40. Therefore, optimal care incorporates joint nephrological and ophthalmic input, which was done in our patient.

Conclusion

This case highlights the need to maintain a high degree of suspicion and close follow-up in young, female patients who present with features of tubulointerstitial nephritis or uveitis. As there are no evidence-based protocols for treating TINU, management relies on case reports and case-series. The recommended treatment for uveitis is topical steroids. However, most cases necessitate systemic therapy with corticosteroids owing to renal involvement or in cases of posterior ocular involvement.

Immunomodulatory drugs may be used in resistant cases. With prompt therapy, prognosis of both renal and ocular involvement is usually favorable, though relapses might occur. Therefore, combined nephrological and ophthalmological care is warranted. Furthermore, there is a need for a multicenter study and registry formation to obtain important clinical data regarding follow-up and treatment of these patients, and a frameshift for implementation of multinational guidelines of treatment and prognosis.

Learning points

-

•In patients presenting with uveitis and/or acute interstitial nephritis, a suspicion of TINU syndrome should be made, especially if young and/or female.

-

•Even when histological features of important tubulointerstitial nephritis and noncaseating granulomata can be found, as in our case, the urinalysis can show only mild urine changes with proteinuria and glucosuria, with no hematuria. In our patient with bilateral uveitis and marked elevation of ESR, a renal biopsy proved useful in guiding therapy.

-

•With prompt ocular and systemic corticosteroid therapy, prognosis of TINU is favorable, despite occasional relapses.

Patient’s perspective

I have to say that the overall care from both the Nephrology and Ophthalmology department was very professional. At first, I was quite shocked after I developed an inflammation of my eye, which did not allow me to see properly. Also, I was surprised that I had additional problems with my kidneys that I did not even notice. After several weeks of staying in the hospital, my nephrologist told me that I would have to undergo a kidney biopsy, the thought of which was quite scary. However, as I had already known the department staff for years, I trusted them fully and was not too worried after the diagnosis of TINU came. The therapy which was offered to me was quite tolerable, though I did not like gaining even more weight after being put on corticosteroids, which the doctors told me could happen. Coming home after more than a month, I am very happy to again attend school, and try to maintain a healthy lifestyle as recommended.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TINU:

-

Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibodies

- anti-ENA:

-

Anti-extractable nuclear antigen antibodies

- anti-DNA:

-

Anti-deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies

- ANCA:

-

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- mCRP:

-

Modified C-reactive protein

- AIN:

-

Acute interstitial nephritis

References

Dobrin RS, Vernier RL, Fish AJ. Acute eosinophilic interstitial nephritis and renal failure with bone marrow-lymph node granulomas and anterior uveitis. Am J Med. 1975;59(3):325–33.

Saarela V, Nuutinen M, Ala-Houhala M, Arikoski P, Rönnholm K, Jahnukainen T. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in children: a prospective multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1476–81.

Mandeville JT, Levinson RD, Holland GN. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46(3):195–208.

Tan Y, Yu F, Qu Z, Su T, Xing GQ, Wu LH, et al. Modified C-reactive protein might be a target autoantigen of TINU syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):93–100.

Kase S, Kitaichi N, Namba K, Miyazaki A, Yoshida K, Ishikura K, et al. Elevation of serum Krebs von den Lunge-6 levels in patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(6):935–41.

Rytkönen S, Ritari J, Peräsaari J, Saarela V, Nuutinen M, Jahnukainen T. IL-10 polymorphisms +434T/C, +504G/T, and -2849C/T may predispose to tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in pediatric population. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):0211915.

Kobayashi Y, Honda M, Yoshikawa N, Ito H. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in 21 Japanese children. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54(3):191–7.

Howell M, Sebire NJ, Marks SD, Tullus K. Biopsy-proven paediatric tubulointerstitial nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(10):1625–30.

Clive DM, Vanguri VK. The syndrome of tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis (TINU). Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):118–28.

Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(3):149–62.

Joyce E, Glasner P, Ranganathan S, Swiatecka-Urban A. Tubulointerstitial nephritis: diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(4):577–87.

Jones NP. The Manchester Uveitis Clinic: the first 3000 patients—epidemiology and casemix. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23(2):118–26.

Amaro D, Carreño E, Steeples LR, Oliveira-Ramos F, Marques-Neves C, Leal I. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;4:1–7.

Okafor LO, Hewins P, Murray PI, Denniston AK. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome: a systematic review of its epidemiology, demographics and risk factors. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):1–9.

Pinheiro MA, Rocha MBC, Neri BO, Parahyba IO, Moura LAR, de Oliveira CMC, et al. TINU syndrome: review of the literature and case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2016;38(1):132–6.

Pakzad-Vaezi K, Pepple KL. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(6):629–35.

Gorrono-Echebarria MB, Calvo-Arrabal MA, Albarran F, Alvarez-Mon M. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is associated with HLA-DR14 in Spanish patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1010–1.

Peräsaari J, Saarela V, Nikkilä J, Ala-Houhala M, Arikoski P, Kataja J, et al. HLA associations with tubulointerstitial nephritis with or without uveitis in Finnish pediatric population: a nation-wide study. Tissue Antigens. 2013;81(6):435–41.

Levinson RD, Park MS, Rikkers SM, Reed EF, Smith JR, Martin TM, et al. Strong associations between specific HLA-DQ and HLA-DR alleles and the tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(2):653–7.

Mackensen F, David F, Schwenger V, Smith LK, Rajalingam R, Levinson RD, et al. HLA-DRB1*0102 is associated with TINU syndrome and bilateral, sudden-onset anterior uveitis but not with interstitial nephritis alone. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(7):971–5.

Reddy AK, Hwang YS, Mandelcorn ED, Davis JL. HLA-DR, DQ class II DNA typing in pediatric panuveitis and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(3):678-686.e2.

Jia Y, Su T, Gu Y, Li C, Zhou X, Su J, et al. HLA-DQA1, -DQB1, and -DRB1 alleles associated with acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in a Chinese population: a single-center cohort study. J Immunol. 2018;201(2):423–31.

Vô B, Yombi JC, Aydin S, Demoulin N, Yildiz H. TINU-associated Fanconi syndrome: a case report and review of literature. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):1–6.

Kamel M, Thajudeen B, Bracamonte E, Sussman A, Lien YHH. Polyuric kidneys and uveitis: an oculorenal syndrome. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:530–3.

Clavé S, Rousset-Rouviere C, Daniel L, Tsimaratos M. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in children and chronic kidney disease. Arch Pediatr. 2019;26(5):290–4.

Lusco MA, Fogo AB, Najafian B, Alpers CE. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(6):e27–8.

Carvalho TJ, Calça R, Cassis J, Mendes A. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in a female adult. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(1).

Sobolewska B, Bayyoud T, Deuter C, Doycheva D, Zierhut M. Long-term follow-up of patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;26(4):1–7.

Baker RJ, Pusey CD. The changing profile of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(1):8–11.

Yang M, Chi Y, Guo C, Huang J, Yang L, Yang L. Clinical profile, ultra-wide-field fluorescence angiography findings, and long-term prognosis of uveitis in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome at one tertiary medical institute in China. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(3):371–9.

Tanaka H, Suzuki K, Nakahata T, Tateyama T, Waga S, Ito E. Repeat renal biopsy in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: report of a case. Jpn J Nephrol. 2001;16:885–7.

Yanagihara T, Kitamura H, Aki K, Kuroda N, Fukunaga Y. Serial renal biopsies in three girls with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(6):1159–64.

Suzuki K, Tanaka H, Ito E, Waga S. Repeat renal biopsy in children with severe idiopathic tubulointerstitial nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19(2):240–3.

Weinstein O, Tovbin D, Rogachev B, Basok A, Vorobiov M, Kratz A, et al. Clinical manifestations of adult tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(5):621–8.

Biester S, Müller C, Deuter CME, Doycheva D, Altpeter E, Zierhut M. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in siblings. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(5):370–2.

Houghton D, Troxell M, Fox E, Rosenbaum J. TINU (tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis) syndrome is not usually associated with IgG4 sclerosing disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):583–4.

Birnbaum AD, Jiang Y, Vasaiwala R, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Bilateral simultaneous-onset nongranulomatous acute anterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(11):1389.

Takemoto Y, Namba K, Mizuuchi K, Ohno S, Ishida S. Two cases of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23(2):255–7.

Li C, Su T, Chu R, Li X, Yang L. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis in Chinese adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):21–8.

Ali A, Rosenbaum JT. TINU (tubulointerstitial nephritis uveitis) can be associated with chorioretinal scars. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(3):213–7.

Hettinga YM, Scheerlinck LME, Lilien MR, Rothova A, De Boer JH. The value of measuring urinary β2-microglobulin and serum creatinine for detecting tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in young patients with uveitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(2):140–5.

Legendre M, Devilliers H, Perard L, Groh M, Nefti H, Dussol B, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in adults. Medicine (United States). 2016;95(26):1–9.

Sawai T, Shimizu M, Sakai T, Yachie A. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome associated with human papillomavirus vaccine. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2016;53(3):190–1.

Ariba YB, Labidi J, Elloumi Z, Selmi Y, Othmani S. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: a report on four adult cases. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2017;28(1):162–6.

Nagashima T, Ishihara M, Shibuya E, Nakamura S, Mizuki N. Three cases of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome with different clinical manifestations. Int Ophthalmol. 2017;37(3):753–9.

Provencher LM, Fairbanks AM, Abramoff MD, Syed NA. Urinary β2-microglobulin and disease activity in patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2018;8(1).

Kanno H, Ishida K, Yamada W, Shiraki I, Murase H, Yamagishi Y, et al. Clinical and genetic features of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome with long-term follow-up. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:1–8.

Zhang H, Wang F, Xiao H, Yao Y. The ratio of urinary α1-microglobulin to microalbumin can be used as a diagnostic criterion for tubuloproteinuria. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2018;7(1):46–50.

Pereira C, Gil J, Leal I, Costa-Reis P, Da SJEE, Stone R. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in children: report of three cases. J Bras Nefrol. 2018;40(3):296–300.

Takeuchi M, Kanda T, Kaburaki T, Tanaka R, Namba K, Kamoi K, et al. Real-world evidence of treatment for relapse of noninfectious uveitis in tertiary centers in Japan: a multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(9):14668.

Abd El Latif E, Abdelhalim AS, Montasser AS, Said MH, Shikhoun Ahmed M, Abdel Kader Fouly Galal M, et al. Pattern of intermediate uveitis in an Egyptian cohort. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(3):524–31.

Çakan M, Yildiz Ekıncı D, Gül Karadağ S, Aktay AN. Etiologic spectrum and follow-up results of noninfectious uveitis in children: a single referral center experience. Arch Rheumatol. 2019;34(3):294–300.

Cao JL, Srivastava SK, Venkat A, Lowder CY, Sharma S. Ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography and OCT findings in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmol Retin. 2020;4(2):189–97.

Roy S, Awogbemi T, Holt RCL. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in children—a retrospective case series in a UK tertiary paediatric centre. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):17.

Kitano M, Tanaka R, Kaburaki T, Nakahara H, Shirahama S, Suzuki T, et al. Clinical features and visual outcome of uveitis in Japanese patients younger than 18 years. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;1–7.

Azar R, Verove C, Boldron A. Delayed onset of uveitis in TINU syndrome. J Nephrol. 2000;13(5):381–3.

Mackensen F, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Enhanced recognition, treatment and prognosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(5).

Nikolić V, Bogdanović R, Ognjanović M, Stajić N. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in children. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2001;129(Suppl):23–7.

Sanchez-Burson J, Garcia-Porrua C, Montero-Granados R, Gonzalez-Escribano F, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in Southern Spain. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32(2):125–9.

Tanaka H, Waga S, Nakahata T, Suzuki K, Ito T, Onodera N, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in two siblings. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):71–4.

Matsuo T. Fluorescein angiographic features of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(1):132–6.

Deguchi HE, Amemiya T. Two cases of uveitis with tubulointerstitial nephritis in HTLV-1 carriers. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47(4):372–8.

Goda C, Kotake S, Ichiishi A, Namba K, Kitaichi N, Ohno S. Clinical features in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):637–41.

Hudde T, Heinz C, Neudorf U, Hoeft S, Heiligenhaus A, Steuhl K-P. Tubulointerstitielle Nephritis mit Uveitis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2002;219(7):528–32.

Howarth L, Gilbert RD, Bass P, Deshpande PV. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in monozygotic twin boys. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19(8):917–9.

Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):222–30.

Lim AKH, Roberts MA, Joon TL, Levidiotis V. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: sore eyes and sick kidneys. Med J Aust. 2005;183(9):477–8.

Li JYZ, Yong TY, Bennett G, Barbara JA, Coates PTH. Human leucocyte antigen DQ alpha heterodimers and human leucocyte antigen DR alleles in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Nephrology. 2008;13(8):755–7.

Svozilková P, Ríhová E, Kontur A, Plsková J, Jeníková D, Kovarík Z. TINU syndrome. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2006;62(4):255–62.

Dusek J, Urbanova I, Stejskal J, Seeman T, Vondrak K, Janda J. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in a mother and her son. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(11):2091–3.

Mortajil F, Rezki H, Hachim K, Zahiri K, Ramdani B, Zaid D, et al. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and anterior uveitis (TINU syndrome): a report of two cases. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2006;17(3):386–9.

Yao Y, Yang JY. Two cases of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in children. Chin J Pediatr. 2007;45(4):310–1.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Maya Petek for assistance with graphical data presentation.

Funding

The authors declare no funding was granted for the publication of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TP and NMV managed the patient, and MF performed the pathological assessment of renal biopsy samples. TP wrote the original manuscript, MF provided pathological images with descriptions, and NMV performed clinical supervision and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her legal guardian for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Petek, T., Frelih, M. & Marčun Varda, N. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in an adolescent female: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15, 443 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03017-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03017-8