Abstract

Background

It is extremely rare for primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas to occur singly in the cranial vault. One case diagnosed as primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is reported, initially misdiagnosed as metastatic skull tumor, complicated with Trousseau syndrome.

Case description

The patient was a 60-year-old Japanese woman with no particular previous medical history. In a head computed tomography examination for vertigo, bone destructive skull tumor covering the right frontal, parietal, and temporal bones was incidentally discovered. As positron emission tomography indicated an abnormal accumulation in the large intestine and multiple cerebral infarctions suspicious of Trousseau syndrome were observed on magnetic resonance images, a metastatic skull tumor due to colorectal cancer was first considered. However, various tumor markers were negative, and colonoscopic biopsy indicated no colorectal abnormality. After pathological examination of the resected tumor, it was diagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The tumor affected muscles and skin but did not develop in the brain or the dura mater. As further general examination revealed no other abnormalities, we considered that it was primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the cranial vault associated with Trousseau syndrome. Treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone and high-dose methotrexate reduced the residual lesion; coagulation abnormalities, which are frequently associated with Trousseau syndrome, also improved.

Conclusions

Skull tumors can result from a variety of malignancies, and their diagnosis may be complicated with Trousseau syndrome. However, even in cases of a single lesion in the cranial vault without invasion of the central nervous system, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, commonly occurs in the midline and deep white matter, such as the periphery of the lateral ventricle, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. Occurrence of DLBCL in the cranial vault is rare and accounts for 0.3–5.0% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [1,2,3]. It might often be difficult to diagnose initially owing to similarities with other skull tumors [4].

Trousseau syndrome is one of the paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that causes neurological symptoms due to the remote effect of latent malignant tumors. Trousseau syndrome causes cerebral infarction due to hypercoagulation associated with malignant tumors [5].

One case diagnosed as primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) complicated with Trousseau syndrome is reported.

Case report

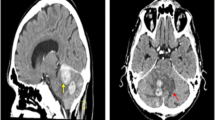

A 60-year-old Japanese woman who had no immunodeficiency and an unremarkable medical history visited our hospital with sudden right facial paralysis and vertigo as the chief complaints. On neurological examination, she had no motor or sensory abnormalities other than facial paralysis and no cranial nerve symptoms. At that time, we detected a bone destructive skull tumor extending from the right frontal bone to the parietal and temporal bones on a head computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1A). However, no obvious abnormalities were observed from visual inspection and palpation of the head.

Preoperative images. A Head computed tomography (CT) showing bone destructive skull tumor spreading from the right frontal bone to the parietal and temporal bones (arrow). B Preoperative T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showing that the legion had invaded the surrounding subcutaneous tissue and temporal muscle. C Diffusion-weighted image showing new multiple cerebral infarctions in the bilateral hemispheres

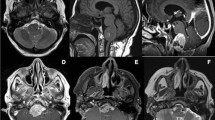

Using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI), the lesion was confirmed to have invaded the surrounding subcutaneous tissue and temporal muscle (Fig. 1B), but it had not yet developed in the brain. Diffusion-weighted imaging revealed multiple acute ischemic lesions in bilateral hemispheres (Fig. 1C). Additionally, we confirmed abnormal accumulations consistent with the bone lesion (Fig. 2A) as well as in the large intestine (Fig. 2B) by positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT). However, no abnormality was detected on colonoscopy, and all tumor markers—carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, α-fetoprotein, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II, sialyl-Lewis X, cancer antigen 125, and β2 microglobulin—were negative. Contrast-enhanced CT did not reveal phlebothrombosis or any abnormal finding in the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The skull tumor was resected for confirming the diagnosis. When the bones were exposed in a wide area by performing a curved skin incision from the anterosuperior portion of the auricle to the midline, bone destruction was found mainly from the frontal bone to the parietal bone, with an abundance of indurated tumor inside (Fig. 3A). The tumor was highly vascularized with temporal muscle/subcutaneous invasion (Fig. 3B). We confirmed that there was no invasion to the dura mater by removing the destructed bone and the fractured pieces in the surrounding area (Fig. 3C). We covered the defective part of the bone with a plate and conducted coagulation for the invasion sites in the muscle. There were no complications due to surgery. Resection of the tumor was confirmed by postoperative MRI. Histopathologically, the resected lesion was diffusely invaded by large atypical cells with a high nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio; there were individual tumor cells with irregular nuclei as well as cells with distinctive nuclear bodies. Mitosis and necrosis were also observed (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemical examination was positive for CD20/CD79a (Fig. 4B, C) and negative for CD3 in terms of atypical cells; the Ki-67 labeling index was approximately 90%. Based on these results, the tumor was identified as a DLBCL. Further examinations were conducted on the basis of the pathological results. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology examination and bone marrow biopsy were both negative for malignant cells. The blood sample was negative for viral markers, including HIV, with no abnormalities in blood counts and images. Coagulative markers indicated an increase in fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products (FDP) (70 μg mL), D-dimer (6.7 μg/mL), and thrombin–antithrombin III complex (TAT) (9.1 μg/L), but protein C and protein S levels were normal. Furthermore, various autoantibody, anticardiolipin antibody, and lupus anticoagulant tests were negative. Vascular stenosis was not observed on magnetic resonance angiogram and contrast-enhanced CT. There were no abnormalities in carotid ultrasonography and 24-hour electrocardiographic monitoring. Transesophageal echocardiography showed no nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis findings and patent foramen ovale.

Intraoperative photographs. A Bone destruction was found mainly from frontal bone to parietal bone with the abundance of indurated tumor inside (arrow). B The tumor was hard and hemorrhagic. C The fractured bone and surrounding bone were removed, and it was confirmed that there was no infiltration into the dura mater

Histopathological findings of the resected skull tumor. A Large atypical cells invaded diffusely, and individual tumor cells with irregular nuclei were observed (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40). B Histological examination showing that the large tumor cells were immunoreactive for CD20 (immunohistochemistry, CD20, ×20). C Histological examination showing that the large tumor cells were immunoreactive for CD79a (immunohistochemistry, CD79, ×20)

Based on all the test results, we confirmed the diagnosis as primary DLBCL of the cranial vault complicated with Trousseau syndrome. Trousseau syndrome was treated with continuous infusion of heparin during the perioperative period. On the third day after surgery, we switched the treatment to oral anticoagulant medication. After completing three courses of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP) and high-dose methotrexate for DLBCL, the patient is demonstrating an asymptomatic, benign course with reduced residual lesions. Her symptoms and coagulation abnormality with Trousseau syndrome improved simultaneously with tumor shrinkage (FDP 4.2 μg/mL, D-dimer 1.1 μg/mL, TAT 3.2 μg L). We are planning to initiate radiation therapy after the completion of four courses.

Discussion

Skull tumors with aggressive bone destruction can arise from a variety of malignancies, including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, chordoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, meningioma, and plasmacytoma. The occurrence of DLBCL restricted to the cranial vault is rare, although there are some reports of such disorders [6,7,8]. Nevertheless, we did not come across any report of primary DLBCL of the cranial vault complicated with Trousseau syndrome in our research.

In general, Trousseau syndrome means “hypercoagulable state associated with malignant tumor or disseminated intravascular coagulation and its accompanying migratory venous or arterial thromboembolism,” but there is no clear diagnostic standard [9]. In the present case, despite the absence of arrhythmia, cardiac disease, collagen disease, and arteriosclerotic lesions, we found coagulation abnormalities and multiple cerebral infarctions in both cerebral hemispheres. Since there was an osteoclastic neoplastic lesion in the skull, we considered Trousseau syndrome with malignant tumor. Although most malignant tumors as a cause of Trousseau syndrome are solid cancers, often identified as gynecologic tumors, the frequency varies depending on reports [10]. Histologically, it often occurs as adenocarcinoma, particularly mucin-producing adenocarcinoma [11], and colorectal cancer has a high incidence (2–15.9%) among malignant tumors [5]. Lymphoma is recognized as a risk factor for Trousseau syndrome by the Khorana score, an observation supported by other research, but they consider blood cell abnormalities and chemotherapy due to lymphoma as a cause of Trousseau syndrome [12, 13]. Lymphoma with no treatment and no blood cell abnormality, as in this case, is unlikely to be considered as a risk of Trousseau syndrome. Chemotherapy for DLBCL simultaneously reduced tumor size and improved the coagulation abnormality with no recurrence of cerebral infarction. Successful treatment of the primary disease thereby improved symptoms of Trousseau syndrome in the present case, similar to what has been observed for other cases [1, 14].

In previous reports, primary DLBCL of the cranial vault was often considered as osteoclastic lesion [15], and intracranial symptoms such as seizure and hemiplegia were reported in some cases [4, 16, 17]. Although there were no intracranial symptoms and no development to the dura mater or the brain in the present case, it was similar to the past cases with regard to the extensive skull destruction. However, it is said that metastatic skull tumors may often have a similar osteoclastic nature and could be very difficult to differentiate from vault lymphoma [18]. According to a report by Uemura et al. comparing vault lymphoma with other skull tumors with regard to osteoclastic patterns, bone destruction of vault lymphoma developed diffusely and gradually, but cortical bone was relatively easy to be maintained and could show uneven bone destruction [19]. In the present case, bone destruction observed on CT scans and in surgical findings was localized in comparison with the lesion area imaged by CEMRI. On the other hand, metastatic skull tumor would have developed to destroy the entire bone structure from the early stage [19].

Conclusion

As skull tumors can result from various malignancies, they may often be difficult to diagnose. Our observations in this case suggest that Trousseau syndrome may develop in association with DLBCL. Furthermore, DLBCL should be considered as a differential diagnosis for all lesions of the cranial vault that lack invasion of the central nervous system.

Availability of data and materials

We make our references in the manuscript available for testing by reviewers.

References

Yoshii Y, Numata T, Ishitobi W, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma complicated by Trousseau’s syndrome successfully treated by a combination of anticoagulant therapy and chemotherapy. Intern Med. 2014;53(16):1835–9.

Kiessling JW, Whitney E, Cathel A, Khan YR, Mahato D. Primary cranial vault non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma mimicking meningioma with positive angiography. Cureus. 2020;12(6):8856.

Fukushima Y, Oka H, Utsuki S, Nakahara K, Fujii K. Primary malignant lymphoma of the cranial vault. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149(6):601–4.

Rezaei-Kalantari K, Samimi K, Jafari M, et al. Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the cranial vault. Iran J Radiol. 2012;9(2):88–92.

Sack GH Jr, Levin J, Bell WR. Trousseau’s syndrome and other manifestations of chronic disseminated coagulopathy in patients with neoplasms: clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic features. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):1–37.

Paige ML, Bernstein JR. Transcalvarial primary lymphoma of bone. A report of two cases. Neuroradiology. 1995;37(6):456–8.

Pardhanani G, Ashkan K, Mendoza N. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the cranial vault presenting with unilateral proptosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142(5):597–8.

Villela LM, Blanco-Salazar A, Caballero R, Borbolla-Escoboza R. Aggressive lymphoma involving intracranial epidural region. J Neurooncol. 2007;83(2):181–2.

Sutherland DE, Weitz IC, Liebman HA. Thromboembolic complications of cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2003;72(1):43–52.

Chaturvedi S, Ansell J, Recht L. Should cerebral ischemic events in cancer patients be considered a manifestation of hypercoagulability? Stroke. 1994;25(6):1215–8.

Evans TR, Mansi JL, Bevan DH. Trousseau’s syndrome in association with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77(12):2544–9.

Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111(10):4902–7.

Ikushima S, Ono R, Fukuda K, Sakayori M, Awano N, Kondo K. Trousseau’s syndrome: cancer-associated thrombosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(3):204–8.

Tachihara M, Nikaido T, Wang X, et al. Four cases of Trousseau’s syndrome associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Intern Med. 2012;51(9):1099–102.

Duyndam DA, Biesma DH, van Heesewijk JP. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the cranial vault; MRI features before and after treatment. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(10):948–50.

Martin J, Ramesh A, Kamaludeen M, Ganesh UK, Martin JJ. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the scalp and cranial vault. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2012;2012:616813.

Asri EAC, Akhaddar A, Baallal H, et al. Primary lymphoma of the cranial vault: case report and a systematic review of the literature. Acta Neurochir Wien. 2012;154(2):257–65.

Kawamoto K, Kawakami K, Iwase M, Suyama T, Li Q, Nakashima Y. Metastatic skull tumor, epidermoid cyst, dermoid cyst, and intraosseous meningioma. No Shinkei Geka. 2004;32(8):895–903.

Umemura T, Nakano Y, Soejima Y, et al. Characteristics of bone destruction in cranial vault lymphoma compared with other skull tumors. J Uoeh. 2019;41(3):335–42.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

We are not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH consulted on the appropriateness of the patient’s initial treatment. HN and KA evaluated images and treatment. HN checked the whole article structure. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Uchida, T., Amagasaki, K., Hosono, A. et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the cranial vault with Trousseau syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15, 431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02979-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02979-z