Abstract

Background

Jejunal lymphatic malformations are congenital lesions that are seldom diagnosed in adults and rarely seen on imaging.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old Caucasian woman was initially diagnosed and treated for mucinous ovarian carcinoma. After an exploratory laparotomy with left salpingo-oophorectomy, a computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated suspicious fluid-containing lesions involving a segment of jejunum and adjacent mesentery. Resection of the lesion during subsequent debulking surgery revealed that the lesion seen on imaging was a jejunal lymphatic malformation and not a cancerous implant.

Conclusions

Abdominal lymphatic malformations are difficult to diagnose solely on imaging but should remain on the differential in adult cancer patients with persistent cystic abdominal lesions despite chemotherapy and must be differentiated from metastatic implants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lymphatic malformations, previously known as “lymphangiomas,” are developmental anomalies of lymphatic ducts that are more commonly found in the head, neck, or axilla. Abdominal lymphatic malformations are exceptionally rare and account for less than 1% of all lymphatic malformations [1]. They can present with symptoms ranging from mild abdominal pain to an acute abdomen. Although lymphatic malformations directly associated with the bowel are rarely, if ever, imaged, computed tomography (CT) occasionally reveals cystic structures on the mesentery that compress adjacent bowel [2]. A definitive diagnosis is typically achieved after surgical excision and histologic examination demonstrate dilated lymphatic channels notable for continuous, flat endothelia [3]. In this case report, we present a 61-year-old woman whose exceptionally rare jejunal lymphatic malformation was seen on CT but was initially believed to be a peritoneal implant from her ovarian carcinoma.

Case presentation

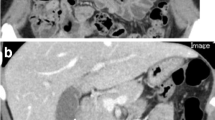

A 61-year-old Caucasian woman presented with 5-year history of abdominal pain and distension, fatigue, and 1-year history of abnormal uterine bleeding. Initial workup revealed a carcinoembryonic antigen value of 8.1 ng/mL (normal < 3.9 ng/mL), cancer antigen-125 value of 134 U/mL (normal < 38.1 ng/mL), and a large left adnexal mass on ultrasound. Preoperative CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis without oral contrast initially revealed hypodense, ovoid lesions in the left lower quadrant mesentery adjacent to a short segment of small bowel (Fig. 1).

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy which confirmed a diagnosis of mucinous ovarian carcinoma. One-month postoperative surveillance CT of the abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast demonstrated marked decrease in ascites and a 7–8-cm segment of small bowel in the left lower quadrant with low-density mural wall and bowel fold thickening. Additionally, there were hypodense ovoid lesions in the adjacent mesentery, which are the same lesions seen on the preoperative CT (Fig. 2). These findings were thought to represent persistent presence of peritoneal and serosal tumor implants.

The patient subsequently began chemotherapy with folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) and completed two treatment cycles. Trastuzumab was then added, and the patient underwent an additional three cycles of FOLFOX–trastuzumab. A repeat abdominopelvic CT 4 months after the exploratory laparotomy showed resolution of ascites, but redemonstrated unchanged findings in the short segment of small bowel and adjacent mesentery in the left lower quadrant. These findings were again thought to represent persistent peritoneal and serosal tumor implants despite chemotherapy.

Shortly after the repeat CT, the patient underwent extensive tumor debulking. Intraoperatively, an 8-cm segment of jejunum with rubbery-like texture and adjacent mesentery was excised (Fig. 3). Histologic examination revealed a lymphatic malformation with variously sized lymphatic channels lined by a single, continuous layer of endothelia (Fig. 4). No residual intraperitoneal tumor was identified. The patient was subsequently discharged with a plan to complete FOLFOX–trastuzumab chemotherapy for her metastatic ovarian carcinoma.

Discussion

Less than 1% of lymphatic malformations occur in the small bowel [4]. While no consensus exists for their development, they likely form when isolated lymphatic channels fail to connect appropriately to more prominent main channels, but evidence suggests that they can also be acquired from traumatic, inflammatory, or iatrogenic processes [5]. In adults, case reports indicate a variable presentation ranging from asymptomatic incidental findings [6] to acute [7] or chronic [8] abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding [9], intussusception [4], and volvulus [10].

When imaged on CT, lymphatic malformations are typically described as cystic mesenteric structures filled with hypodense fluid that compress immediately adjacent bowel [8]. Contrast enhancement may reveal the presence of septae [2], but the cystic portion of the malformation is either filled with nonenhancing fluid, or rarely, with hemorrhage or calcifications [12].

Our patient’s lymphatic malformation had several features that mimicked peritoneal and serosal mucinous tumor implants. Tumor implants typically show thicker walls and septa, “scalloping” of visceral surfaces due to compressive forces from mucin produced by the peritoneal implants, and heterogeneous internal densities [13]. The ovoid mesenteric fluid-containing structures in our patient were part of the lymphatic malformation; however, in the setting of mucinous ovarian tumor, they mimicked peritoneal carcinomatosis with trapped malignant ascites. Additionally, lymphatic fluid within the jejunal wall likely caused the hypodense intramural thickening that mimicked serosal tumor implants.

Given the rarity of lymphatic malformations of the bowel and mesentery, there are few radiology studies devoted to diagnosis and characterization; however, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging may be a potentially useful test in distinguishing lymphatic malformations from mucinous tumor implants [14]. Lymphatic malformations typically have high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and lower internal T1 signal [2]. Mucinous tumors, on the other hand, typically have internally heterogeneous T1 and T2 signal intensities, although tumors containing a high concentration of mucin could display higher T1 and lower T2 signal intensities [15].

Gastrointestinal lymphatic malformations are typically treated with surgical removal considering their potential for mass effects, although sclerotherapy [16] and lymphovenous anastomosis [17] have been successfully reported. Histologic examination of the removed malformations typically show dilated lymphatic channels with flat, continuous endothelia [3]. They can be classified as macrocystic, microcystic, or mixed [19] depending on their microscopic size, although this classification is difficult to interpret radiologically.

Conclusion

Lymphatic malformations of the small bowel are exceptionally rare anomalous developments of the lymphatic system. In the setting of mucinous tumors, lymphatic malformations with their variable presentation and nonspecific imaging appearance can present a diagnostic challenge as they mimic tumor deposits. Increased awareness of this entity may help improve patient care.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FOLFOX:

-

Folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin

References

Roisman I, Manny J, Fields S, Shiloni E. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma. Br J Surg. 1989;76(5):485–9.

Levy AD, Cantisani V, Miettinen M. Abdominal lymphangiomas: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(6):1485–91.

Rieker RJ, Quentmeier A, Weiss C, Kretzschmar U, Amann K, Mechtersheimer G, Bläker H, Otto HF. Cystic lymphangioma of the small-bowel mesentery. Pathol Oncol Res. 2000;6(2):146–8.

Samuelson H, Giannotti G, Guralnick A. Jejunal lymphangioma causing intussusception in an adult: an unusual case with review of the literature. Ann Med Surg. 2018;1(34):39–42.

Kennedy TL. Cystic hygroma-lymphangioma: a rare and still unclear entity. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(S1):1.

Lawless ME, Lloyd KA, Swanson PE, Upton MP, Yeh MM. Lymphangiomatous lesions of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic study and comparison between adults and children. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144(4):563–9.

Jayasundara JA, Perera E, de Silva MV, Pathirana AA. Lymphangioma of the jejunal mesentery and jejunal polyps presenting as an acute abdomen in a teenager. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99(3):108–9.

Aprea G, Guida F, Canfora A, Ferronetti A, Giugliano A, Ciciriello MB, Savanelli A, Amato B. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma in adult: a case series and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2013;13(1):1–5.

Tan B, Zhang SY, Wang YN, Li Y, Shi XH, Qian JM. Jejunal cavernous lymphangioma manifested as gastrointestinal bleeding with hypogammaglobulinemia in adult: a case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(1):140.

Suthiwartnarueput W, Kiatipunsodsai S, Kwankua A, Chaumrattanakul U. Lymphangioma of the small bowel mesentery: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2012;18(43):6328.

Allen JG, Riall TS, Cameron JL, Askin FB, Hruban RH, Campbell KA. Abdominal lymphangiomas in adults. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(5):746–51.

Wohlgemuth WA, Brill R, Dendl LM, Stangl F, Stoevesandt D, Schreyer AG. Abdominal lymphatic malformations. Radiologe. 2018;58(1):29–33.

Levy AD, Shaw JC, Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(2):347–73.

Romeo V, Maurea S, Mainenti PP, Camera L, Aprea G, Cozzolino I, Salvatore M. Correlative imaging of cystic lymphangiomas: ultrasound, CT and MRI comparison. Acta Radiologica Open. 2015;4(5):2047981614564911.

Lee NK, Kim S, Kim HS, Jeon TY, Kim GH, Kim DU, Park DY, Kim TU, Kang DH. Spectrum of mucin-producing neoplastic conditions of the abdomen and pelvis: cross-sectional imaging evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(43):4757.

Madsen HJ, Annam A, Harned R, Nakano TA, Larroque LO, Kulungowski AM. Symptom resolution and volumetric reduction of abdominal lymphatic malformations with sclerotherapy. J Surg Res. 2019;1(233):256–61.

Ishiura R, Mitsui K, Danno K, Banda CH, Inoue M, Narushima M. Successful treatment of large abdominal lymphatic malformations and chylous ascites with intra-abdominal lymphovenous anastomosis. J Vasc Surg. 2020.

Limaiem F, Khalfallah T, Marsaoui L, Bouraoui S, Lahmar A, Mzabi S. Jejunal lymphangioma: an unusual cause of intussusception in an adult patient. Pathologica. 2015;107(1):19–21.

ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies: 2018 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. http://issva.org/classification. Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT was the attending physician who performed the procedure and managed patient care. MR, TLB, and Ch.C collected patient data. RH and JGB analyzed patient imaging. Ca.C analyzed patient pathology. All authors were active in manuscript drafting, revision, and final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of anonymized case details.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rupasinghe, M., Houshyar, R., Chahine, C. et al. A 61-year-old woman with jejunal lymphatic malformation visualized on computed tomography: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15, 302 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02872-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02872-9