Abstract

Background

Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are sympathetic or parasympathetic tumors derived from the paraganglia and the adrenal medulla, respectively. Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas can be sporadic or familial, the latter frequently being multifocal and possibly due to succinate dehydrogenase complex genes mutations. In addition, 12% of sporadic paragangliomas are related to covered succinate dehydrogenase complex mutations. The importance of identifying succinate dehydrogenase complex mutations is related to the risk for these patients of developing multiple tumors, including non-endocrine ones, showing an aggressive clinical presentation.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 45-year-old Caucasian man with an indolent mass in his neck. Ultrasound of his neck, magnetic resonance imaging, and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N(I),N(II),N(III),N(IIII)-tetraacetic acid(D)-Phe(1)-thy(3)-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC) positron emission tomography-computed tomography and endocrine work-up were consistent with a carotid body paraganglioma with concomitant nodal enlargement in several body regions, which turned out to be a follicular lymphoma at histology. He was found to carry a germline Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene (SDHB) mutation.

Conclusion

It is crucial to look for a second malignancy in the case of a paraganglioma demonstrating succinate dehydrogenase complex germline mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The terms paraganglioma (PGL) and pheochromocytoma (PHEO) refer to sympathetic or parasympathetic tumors arising from the paraganglia and the adrenal medulla, respectively [1,2,3]; PGL and PHEO together are named as PPGL. The annual incidence of PPGL is up to 3/million population [4]. Hereditary PPGLs represent 40% of the cases and are characterized by multifocal lesions in 35–50% of the patients [1, 3, 5, 6]. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) germline mutations represent a possible cause of hereditary PPGL, but have also been reported in 12% of sporadic cases [1]. Germline mutations in SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes have been found in PPGL, but also in gastrointestinal stromal tumors [2, 7]. Genetic screening of patients with SDH is crucial since hereditary forms are associated with a dismal prognosis and a high risk of developing other tumors [2, 3]. In particular, SDHB germline mutations show significant malignancy rates, which are higher than those found in patients with PPGL bearing different SDH germline mutations [8].

This case report describes the association of a neck PGL with a follicular lymphoma in a patient with a germline SDHB mutation.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 45-year-old Caucasian man presenting with an indolent mass in his neck of 4 months’ duration, who was otherwise in good clinical condition. He did not take any prescribed medications and did not report any history of allergy, tobacco smoking, fever, sweating, headache, or hypertension. Familial anamnesis was negative. At a physical examination his thyroid appeared normal, while a subcutaneous 2 cm swelling of his neck was present at the superior margin of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle. The mass was indolent and of parenchymatous consistency at palpation, mobile with respect to the surrounding planes. Palpation also revealed a right submandibular 1.5 cm lymph node enlargement. Routine laboratory parameters were normal.

He was subjected to ultrasonography (US) of his neck, which showed a 2.2 × 2.2 × 1.7 cm homogeneously hypoechoic oval lesion at the carotid bifurcation, with clear-cut margins, markedly vascularized at color-Doppler US. His thyroid had normal morphology and volume, while bilateral lymph node enlargement was observed at lateral cervical level II, devoid of characteristics suspicious for metastases (Fig. 1).

An endocrine work-up was requested, including urinary 24-hour catecholamines and metanephrines, plasma calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, and chromogranin A; all were found to be in the normal range.

He underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his neck that showed a 2.3 × 2.5 cm neck mass, isointense to the muscular tissue on T1-weighted images (T1-wi) and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (T2-wi). After contrast administration the lesion showed marked vascularization and intralesional serpiginous areas. Several bilateral cervical lymph nodes were observed with axial maximum diameter of 1.2 × 0.8 cm and 1 × 0.9 cm at the I and II levels (Fig. 2).

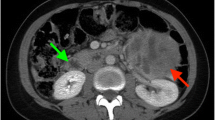

On the basis of US and MRI, a PGL was suspected. A 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N(I),N(II),N(III),N(IIII)-tetraacetic acid(D)-Phe(1)-thy(3)-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC) positron emission tomography (PET)-computed tomography (CT) evaluation was performed, showing an intense focal uptake with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 92.4. Weak lymph node uptake was found in the following regions: lateral cervical, hilar-mediastinal, peribronchial, axillary, and inguinal stations, with a SUVmax of 3.9 in the pulmonary left hilum (Fig. 3).

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N(I),N(II),N(III),N(IIII)-tetraacetic acid(D)-Phe(1)-thy(3)-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC) positron emission tomography/computed tomography axial fused images findings. a Intense focal uptake (maximum standardized uptake value 92.4) in the neck mass, strongly suggestive of paraganglioma; b hilar-mediastinal and peribronchial weak uptake (maximum standardized uptake value 3.9 in the pulmonary left hilum); c axillary and d inguinal weak uptake

According to current guidelines [3], our patient was submitted to genetic testing, including investigation for germline RET and succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHx) mutations. Germline RET mutation testing was performed by direct sequencing as described before [9] and did not disclose any significant mutation. Germline SDHx mutation testing was performed on leukocyte DNA by a next-generation sequencing (NGS) method based on capture technology (probe; IDT), evaluating the presence of point mutations, small deletions, or insertion mutations in the coding region of the SDHB, SDHA, SDHD, SDHAF2, SDHC genes and flanking intronic regions by amplification and direct sequencing. The results of the genetic test of our patient showed the presence of a germline mutation in exon 7 of the SDHB gene. The sequence variant c.689>A; p.Arg230His in heterozygosis was confirmed in a second genomic DNA sample. This variant causes the replacement of the amino acid arginine with a histidine at SDHB protein codon 230. The arginine residue is highly conserved in the course of evolution. Moreover, this variant is present in the population database with a very low frequency, having been identified in one allele out of 251.416 studied. This variant is reported by multiple sources as causative, being classified as pathogenetic, and associated with PGL. The family history of our patient was negative for PPGL or other endocrine neoplasms.

Our patient underwent surgery and histology was consistent with a carotid body PGL. Due to the presence of a germline SDHB gene mutation, a second malignancy was suspected; therefore, accurate histology examination was also pursued for the neck lymph nodes resected during surgery. In fact, a follicular lymphoma was documented as grade 1 according to the histological classification of the World Health Organization (WHO). The hematological assessment of our patient followed European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines; therefore, a contrast-enhanced CT scan of his neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis with an 18FDG (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose)-PET examination established a stage IIIA in accordance with the Ann Arbor classification system [10]. A clinical follow-up with blood test (including a complete blood count, creatinine, uric acid, aspartate aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, total protein, serum protein electrophoresis, and beta-2 microglobulin) and US examination at 3 months was performed, the results were normal. Chemotherapy was not deemed necessary.

Discussion and conclusions

This case report underlines the importance of genetic screening in patients with PPGL, since second malignancies associated with hereditary forms are not rare. Most sporadic PGLs are benign and their prognosis is related to the tumor site: those arising at the carotid body have a better outcome as compared to those located at the skull base (jugular foramen, middle ear, and along the vagus nerve) [11]. A carotid PGL in a SDHB gene mutation carrier is rarely the first manifestation, since SDHB-related PGLs are usually found in extra-adrenal abdominal sites [8]. In fact, these tumors frequently produce high amounts of catecholamines, with associated PHEO-like clinical manifestations. By contrast, our patient showed a hypervascular, well-circumscribed, and asymptomatic enlarging soft tissue lesion in his neck, without adrenergic symptoms such as hypertension, headache, shaking, or weight loss. In our case, clinical manifestation was more consistent with a sporadic PGL that is mostly asymptomatic; when not, it may manifest clinically either as lateral cervical pulsatile mass or with symptoms (dysphagia, anisocoria, dysphonia, and deafness) due to compression and/or displacement of neighboring nerve structures [12]. Once again, our case underlines the importance of a correct genetic investigation, even in the absence of family history and of specific symptoms.

On the other hand, imaging was highly suggestive because in our patient the carotid body PGL appeared at US as a solid, hypoechoic, ovoid, well-defined mass, with a homogeneous structure; at Doppler US the mass appeared markedly hypervascular [13]. Similarly, MRI was highly indicative of PGL, since the tumor had a low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-wi and proton density-weighted sequences and a markedly high signal intensity on T2-wi. On the other hand, the pathognomonic “salt-and-pepper” pattern was not evident, in keeping with its inconstant presence [11].

Since a PGL was suspected, in the absence of catecholamine-related symptoms and of evidence of elevated urinary catecholamine levels, the choice for a 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT was appropriate, since 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) PET or 18F-DOPA PET/CT may return false negative results [14]. On the other hand, 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT may identify lesions different from PGL and in this case showed multiple lymph node faint uptake sites. However, an US examination did not indicate a metastatic suspicion, and, together with 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT, pointed to the presence of inflammatory lymph nodes. On the basis of the results of the genetic testing and of the presence of abdominal 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT uptake, a second malignancy could not be ruled out, supporting the indication for lymphadenectomy during PGL surgery. In fact, a follicular lymphoma was discovered. It has been previously reported that follicular lymphomas express somatostatin receptors, in keeping with 68Ga-DOTATOC PET uptake in our case [15].

Among the reported malignancies associated with SDHx mutations, the presence of a malignant B cell lymphoma has been reported only in one Japanese patient bearing a G106D alteration in exon 4 of the SDHD gene, who developed the disease 5 years after PGL surgery [16]. In addition, genetic derangements in the SDHD gene have been found in other cases: a silent single nucleotide polymorphism was identified in three Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines and in one Burkitt’s lymphoma sample [1, 17].

The association of a SDHB germline mutation with lymphoproliferative disorders, however, is not novel. Cases of SDHB carriers with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [18] or Hodgkin lymphoma [19] have been reported. In addition, patients with PGL with synchronous or metachronous low-grade B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma [20] and follicular lymphoma [21] have been described, but germline mutations were not investigated. Therefore, our case represents the first association between a SDHB germline mutation and a follicular lymphoma. To date, studies reporting a predisposition to lymphoid malignancies in patients with SDHx mutations are still lacking; also, SDHx genes are not routinely evaluated in individuals with non-endocrine cancers [19].

We conclude that in cases of hereditary PPGLs, other malignancies should be looked for, including hematological disorders.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, because no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- 18FDG:

-

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ESMO:

-

European Society for Medical Oncology

- MIBG:

-

123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PGL:

-

Paraganglioma

- PHEO:

-

Pheochromocytoma

- PPGLs:

-

Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas

- SDH:

-

Succinate dehydrogenase

- SDHx:

-

Succinate dehydrogenase complex

- SUVmax:

-

Maximum standardized uptake value

- T1-wi:

-

T1-weighted images

- T2-wi:

-

T2-weighted images

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: From genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:101–11.

Aldera AP, Govender D. Gene of the month: SDH. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:95–7.

Plouin PF, Amar L, Dekkers OM, Fassnacht M, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Lenders JWM, et al. European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for long-term follow-up of patients operated on for a phaeochromocytoma or a paraganglioma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174:G1–10. Available from: https://eje.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/eje/174/5/G1.xml

Turchini J, Cheung VKY, Tischler AS, De Krijger RR, Gill AJ. Pathology and genetics of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Histopathol. 2018;72:97–105. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/his.13402

Gujrathi CS, Donald PJ. Current trends in the diagnosis and management of head and neck paragangliomas. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:339–42. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00020840-200512000-00001

Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L. Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes. 2008 May 21 [Updated 2018 Oct 4]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1548/.

Taïeb D, Kaliski A, Boedeker CC, Martucci V, Fojo T, Adler JR, et al. Current Approaches and Recent Developments in the Management of Head and Neck Paragangliomas. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:795–819. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/35/5/795/2354651

Welander J, Söderkvist P, Gimm O. Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R253–76. Available from: https://erc.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/erc/18/6/R253.xml

Pasini B, Rossi R, Ambrosio MR, Zatelli MC, Gullo M, Gobbo M, et al. RET mutation profile and variable clinical manifestations in a family with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and Hirschsprung’s disease. Surgery. 2002;131:373–81.

Dreyling M, Ghielmini M, Rule S, Salles G, Vitolo U, Ladetto M, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:v83–90.

Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, et al. Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: Imaging features. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:492–504.

Casagranda G, Dematte S, Donner D, Sammartano S, Rozzanigo U, Peterlongo P, et al. Paragangliomas in an endemic area: from genetics to morphofunctional imaging. A pictorial essay. Radiol Med. 2012;117:471–87.

Demattè S, Di Sarra D, Schiavi F, Casadei A, Opocher G. Role of ultrasound and color Doppler imaging in the detection of carotid paragangliomas. J Ultrasound. 2012;15:158–63.

Khan MU, Khan S, El-Refaie S, Win Z, Rubello D, Al-Nahhas A. Clinical indications for Gallium-68 positron emission tomography imaging. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:561–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0748798309000110

Ruuska T, Ramírez Escalante Y, Vaittinen S, Gardberg M, Kiviniemi A, Marjamäki P, et al. Somatostatin receptor expression in lymphomas: a source of false diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor at 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT imaging. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2018;57:283–9.

Ogawa K, Shiga K, Saijo S, Ogawa T, Kimura N, Horii A. A novel G106D alteration of the SDHD gene in a pedigree with familial paraganglioma. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140A:2441–6. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ajmg.a.31444

Bik-Yu Hui A, Lo K-W, Yat-Yee Chan S, Kwong J, Siu-Chung Chan A, Huang DP. Absence of SDHD mutations in primary nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:875–7. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ijc.10066

Baysal BE. A recurrent stop-codon mutation in succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene in normal peripheral blood and childhood T-cell acute leukemia. PLoS One. 2007;2:e436.

Renella R, Carnevale J, Schneider KA, Hornick JL, Rana HQ, Janeway KA. Exploring the association of succinate dehydrogenase complex mutations with lymphoid malignancies. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:507–11.

Rijken JA, Niemeijer ND, Leemans CR, Eijkelenkamp K, der Horst-Schrivers ANA v, van Berkel A, et al. Nationwide study of patients with head and neck paragangliomas carrying SDHB germline mutations. BJS Open. 2018;2:62–9.

Carbone A, Tibiletti MG, Canzonieri V, Rossi D, Perin T, Bernasconi B, et al. In situ follicular lymphoma associated with nonlymphoid malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:603–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript draft and the research about current literature with the support of AC in the final version. LM found the case. MCZ and MRA contributed to genetic testing. MG, MCZ, and MRA supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report does not involve any active intervention for patients, and therefore ethics approval is waived.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Marchetti, L., Perrucci, L., D’Ercole, F. et al. Neck paraganglioma and follicular lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 376 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2323-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2323-1