Abstract

Background

Intradural extramedullary spinal metastasis is a relatively rare condition. Furthermore, there are few reports with the initial presentation being a neurological symptom from an intradural metastasis. We report a case of a patient with metastasis to the cauda equina from breast cancer found due to neurological symptoms as the initial presentation.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old Japanese woman who was previously healthy presented to our hospital with bilateral severe buttock and lower extremity pain without any history of injury. A solitary intradural cauda equina mass was found by magnetic resonance imaging at the L2/3 level, and we suspected a schwannoma initially. The patient hoped to undergo surgery due to the severe pain. However, the chest computed tomographic scan obtained to assess the patient’s general status showed the suspected breast cancer of the left side and a lung metastasis. Hence, we considered the possibility of cauda equina tumor metastatic from the breast cancer. We performed an L1–3 laminectomy and tumor extirpation. The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma. After surgery, she had relief from pain, and her status remained satisfactory until she died 9 months after surgery.

Conclusions

It is difficult to clarify whether the cauda equina tumor is benign or malignant based only on Magnetic resonance imaging findings. Clinicians should consider the possibility of metastasis when planning the surgery for intradural cauda equina tumor extirpation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Metastasis to the spinal vertebral column is relatively common. Sometimes patients have severe pain or a neurological deficit through compression of the spinal cord or the cauda equina because of structural instability or pathological fracture. By contrast, the major pathology of intradural tumor in the cauda equina is schwannoma, and most are benign [1, 2]. Otherwise, intradural extramedullary metastasis is an extremely rare condition [3,4,5]. There are few reports of metastasis to the cauda equina, and the origins were kidney, lung, and breast cancer [6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, it is infrequent that a cancer initially presents with neurological symptoms due to compression of the cauda equina. We report a case of a patient with metastasis from breast cancer to the cauda equina initially presenting with neurological symptoms.

Case presentation

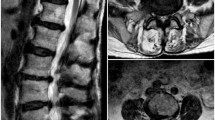

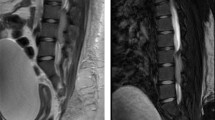

After 1 month of conservative treatment elsewhere, a 76-year-old Japanese woman who was previously healthy presented at our hospital with bilateral severe buttock and lower extremity pain, without a history of injury. She had a history of diabetes, hypothyroidism, and right breast cancer treated surgically 30 years previously. She had no appreciable familial or psychosocial history. Examination revealed the following: severe pain in the buttocks and posterior femoral area, positive straight-leg-raising tests at 30 degrees bilaterally, positive Valleix pain point and superior gluteal nerve pain point tests bilaterally, and negative femoral nerve-stretching tests bilaterally. The patient’s visual analogue scale (VAS; 100 mm) scores for lower extremity pain and numbness were 100/100 mm. By contrast, she had no motor deficit or dysfunction of the bladder or bowel. X-ray findings showed mild spondylosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a solitary intradural extramedullary mass at L2/3 with low T1, high T2, and uniform contrast enhancement with gadolinium (Fig. 1a–c). Myelography showed a total block of contrast below L2/3 and capping of contrast by the mass (Fig. 1d). The diagnosis was a solitary intradural extramedullary cauda equina tumor (a suspected schwannoma). The patient desired tumor extirpation because of the severe pain, so we evaluated her general status. A chest computed tomographic scan showed a suspected left breast cancer and lung metastasis (Fig. 2a, b). Brain MRI showed one small mass in the temporal lobe of the left side with a diameter of about 5 mm, a suspected metastasis (Fig. 2c). We considered a cauda equina tumor metastatic from the breast cancer. After obtaining informed consent, we performed an L1–3 laminectomy and tumor extirpation. Bloody cerebrospinal fluid was observed after the dura mater incision was made. The tumor was involved with the intact cauda equina, and careful division of adhesions was performed. After cutting the filum terminale (conglutinated with the tumor), the tumor was extirpated en bloc (Fig. 3).

a–c Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging. a T1-weighted image. b T2-weighted image. c T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced image. Intradural extramedullary mass at the level of L2–L3 showing T1-low, T2-high signals enhanced uniformly with gadolinium (arrow). d Lateral myelography showing a total block of contrast below the level of L2–L3 and capping of contrast by the mass (arrowhead)

a Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) mediastinal window showing the suspected breast cancer on the left side (arrow) and lung metastasis (arrowhead). b Plain CT lung window showing the suspected lung metastasis (arrowhead). c Axial magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain with T1-weighted gadolinium contrast enhancement showing one small coin lesion in the temporal lobe of the left side with a diameter of about 5 mm, a suspected metastasis (arrowhead)

Postoperatively, the patient experienced pain relief. The pathology of the metastasis was adenocarcinoma. The result of cerebrospinal fluid cytology was negative. The patient started chemotherapy for breast cancer. At the 3-month postoperative follow-up, her VAS score was decreased for the lower extremity pain (from 100 to 0 mm) and numbness (from 100 to 20 mm). MRI showed no local relapses at the surgical incision. The lower extremity pain relief was maintained and was satisfactory during the postoperative course. Radiation therapy was performed to treat the brain metastasis after the surgery. The patient died 9 months postoperatively of Trousseau syndrome and brain metastasis due to breast cancer.

Discussion and conclusions

Intradural metastases are relatively rare compared with metastases to the vertebral column. The few reports of intradural metastases indicate that the most common primary site is the lung (40–85%), followed by breast cancer and renal cell cancer [2, 6, 8,9,10]. In most cases, the diagnosis of intradural metastasis is relatively straightforward because the primary site has already been treated with surgery. By contrast, in our patient, cancer in the right breast was cured because appropriate surgery had been performed 30 years ago and there had been no metastases. Therefore, we first diagnosed the mass as a solitary intradural extramedullary cauda equina tumor suspected of being a schwannoma. However, after checking the patient’s general status, we considered the possibility of a metastatic cauda equina tumor from cancer in the left breast. Our patient’s case is considered quite rare because the initial symptoms were low back and lower extremity pain presenting as cauda equina syndrome. To our knowledge, there are only two reports in the literature of spinal metastasis of occult lung cancer causing cauda equina syndrome [2, 11]. According to one of the reports, as in our patient’s case, MRI of the intradural metastasis in the cauda equina appeared similar to that of intradural nerve sheath tumor, and a diagnosis by MRI alone was difficult because the primary lesion was unknown [2]. In addition, in our case, myelography was performed before surgery. A previous report indicated the utility of myelography in lumbar canal stenosis [12]. Furthermore, when planning surgery for spinal cord tumors such as intradural schwannoma, myelography is useful to confirm respiratory fluctuation of the tumor. If a respiratory fluctuation of the tumor is observed, the wide range of laminectomy is needed. In our patient’s case, respiratory fluctuation of the tumor was not observed, and it was difficult to differentiate schwannoma from cauda equina metastasis. Nevertheless, our patient’s case indicates that we should consider the possibility of metastasis in planning surgery for extirpation of a tumor in the cauda equina.

Four pathways for metastatic tumor spread to the spine are hypothesized as follows: hematogenous dissemination (via an artery), through the paravertebral plexus of veins (Batson’s plexus), direct invasion of the bone, and dissemination through cerebrospinal fluid [2, 9, 13, 14]. Generally, metastatic tumors are entrapped by the lung in the hematogenous dissemination pathway. Indeed, multiple metastases to the lung were observed in our patient. In addition, only one small lesion of brain metastasis was found in our patient, which suggested that the pathway through cerebrospinal fluid was not primal. Hence, we speculate that the pathway for metastasis to the cauda equina is through Batson’s plexus and that that resulted in the metastasis to the brain.

Intradural metastases are a form of terminal stage cancer. The survival rate is in the range of 6–9.4 months despite extirpation surgery [15]. Our patient died 9 months after surgery, which is consistent with other reports. However, the patient was quite satisfied with the surgery because her low back and lower extremity pain was relieved substantially. Surgical treatment may be a favorable option to improve the quality of life in such cases, even if the patient’s prognosis is not good [16].

In conclusion, it is difficult to clarify whether tumors in the cauda equina are benign or malignant on the basis of MRI findings alone. Clinicians should consider the possibility of metastasis when planning surgery to extirpate tumors from the intradural cauda equina. Although the prognosis for such metastatic tumors in the cauda equina is not good, surgical treatment should be considered if the patient has severe pain that prevents an acceptable quality of life.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting our findings is contained within the report.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Ker NB, Jones CB. Tumours of the cauda equina: the problem of differential diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:358–62.

Kotil K, Kilinc BM, Bilge T. Spinal metastasis of occult lung carcinoma causing cauda equina syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:372–5.

Chow TS, McCutcheon IE. The surgical treatment of metastatic spinal tumors within the intradural extramedullary compartment. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:225–30.

Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227–33.

Perrin RG, Livingston KE, Aarabi B. Intradural extramedullary spinal metastasis: a report of 10 cases. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:835–7.

Ito K, Miyahara T, Goto T, Horiuchi T, Sakai K, Hongo K. Solitary metastatic cauda equina tumor from breast cancer: case report. Neurol Med Chir. 2010;50:417–20.

Kubota M, Saeki N, Yamaura A, Iuchi T, Ohga M, Osato K. A rare case of metastatic renal cell carcinoma resembling a nerve sheath tumor of the cauda equina. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:530–2.

Lyons MK. Metastatic breast carcinoma diagnosed by nerve root biopsy for the cauda equina syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:550–1.

Takada T, Doita M, Nishida K, Miura J, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M. Unusual metastasis to the cauda equina from renal cell carcinoma. Spine. 2003;28:E114–7.

Ji GY, Oh CH, Kim SH, Shin DA, Kim KN. Intradural cauda equina metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report with literature review of 10 cases. Spine. 2013;38(18):E1171–4.

Xiong J, Zhang P. Cauda equina syndrome caused by isolated spinal extramedullary-intradural cauda equina metastasis is the primary symptom of small cell lung cancer: a case report and review of the literatrure. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(6):10044–50.

Eadsforth T, Niven S, Barrett C. The utility of myelography in lumbar canal stenosis. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26(4):578–9.

Batson OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940;112:138–49.

Ghosh S, Weiss M, Streeter O, Sinha U, Commins D, Chen TC. Drop metastasis from sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: clinical implications. Spine. 2001;26:1486–91.

Wostrack M, Pape H, Kreutzer J, Ringel F, Meyer B, Stoffel M. Surgical treatment of spinal intradural carcinoma metastases. Acta Neurochir. 2012;154:349–57.

Tokuhashi Y, Uei H, Oshima M. Classification and scoring systems for metastatic spine tumors: a literature review. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2017;1:44–55.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this work were presented at the 56th annual meeting of the Kanto Society of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Tokyo, Japan, March 25–26, 2016.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grant 16K20072 for the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HT, YaA, TF, MK, MasY, and SO conceived of the study. KK and HT drafted the manuscript. HT, YaA, TF, MK, and MY performed the literature search. KK, HT, MI, AO, AN, MS, YoA, JS, ST, ManY, KY, and KN contributed to clinical management of the patient. HT, MI, AO, and KK performed the surgery of this patient. MasY and SO revised the manuscript critically and approved the modified text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Toho University Sakura Medical Center (S18058).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koyama, K., Takahashi, H., Inoue, M. et al. Intradural metastasis to the cauda equina found as the initial presentation of breast cancer: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 220 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2155-z