Abstract

Background

Insulin autoimmune syndrome is a rare cause of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia characterized by autoantibodies to human insulin without previous insulin use. We report a case of a patient with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia possibly caused by insulin antibodies induced by insulin analogs and a novel therapeutic measure for this condition.

Case presentation

An 84-year-old Japanese man with a 28-year history of type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, treated with biphasic insulin aspart 30, experienced persistent early morning hypoglycemia with daytime hyperglycemia. Despite discontinuation of biphasic insulin aspart 30, the condition persisted even after the patient ate small, frequent meals. Sodium bicarbonate was administered to correct the chronic metabolic acidosis, which then rectified the early morning glucose level.

Conclusions

We believe this to be the first published case of a therapeutic approach to the treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia associated with insulin antibodies that factors in blood pH and the correction of acidosis using sodium bicarbonate, which physicians could consider.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Insulin autoimmune syndrome (IAS) is a rare cause of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia characterized by high titers of autoantibodies to human insulin in individuals without previous insulin use [1]. The antibodies in IAS have lower affinity and higher capacity than non-IAS antibodies. Although several therapeutic approaches to IAS have been reported, the optimal treatment is yet to be found [2]. We report a case of a patient with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia possibly caused by insulin antibodies induced by insulin analogs and a novel therapeutic measure for this condition.

Case presentation

An 84-year-old Japanese man was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at 58 years of age in 1987. He received human insulin treatment for 20 years, but in 2011, biphasic human insulin 30 was changed to biphasic insulin aspart 30 (BIAsp 30). He had stage 4 chronic kidney disease due to nephrosclerosis, renal anemia, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, and sleep apnea syndrome. He had been taking the following medications: amlodipine 10 mg/day, rosuvastatin 2.5 mg/day, and febuxostat 20 mg/day. He drank alcohol occasionally and had smoked one to two packs of cigarettes daily for 50 years when he quit 15 years ago. He did not have any food or drug allergies. His family and social histories were not remarkable. His environmental history revealed no abnormalities. He was a retired company director. From January 2015, he experienced persistent early morning hypoglycemia (< 50 mg/dl) with daytime hyperglycemia. Despite reduction of BIAsp 30 dosage, early morning hypoglycemia concomitant with disturbance of consciousness continued to occur. Therefore, he was admitted to our hospital in February 2015.

On examination, the patient’s temperature was 36.3 °C, pulse 64 beats/min, blood pressure 126/72 mmHg, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation 96% while breathing ambient air. He was alert and oriented to time and place on admission. Neurological examination revealed intact cranial nerves, normal limb power and sensation, and absence of cerebellar signs. No changes in sensorium or psychotic features were noted. Other physical examinations revealed no abnormalities. Laboratory findings on admission were as follows: fasting plasma glucose, 82 mg/dl; hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), 7.0%; and glycoalbumin, 21.4%. More laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Imaging studies, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, showed no significant change.

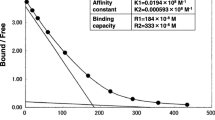

Although BIAsp 30 was discontinued after admission, early morning hypoglycemia with daytime hyperglycemia continued even after eating small frequent meals (a four or six meals per day eating pattern). Fasting blood samples revealed a plasma glucose level of 28 mg/dl, immunoreactive insulin > 2000 μIU/ml, C-peptide 3.03 ng/ml, and high titers of insulin antibody (IA) (> 50 U/ml). IA binding rate was at a high level (86.3%). Scatchard analysis showed an affinity contact (K1) of 0.00256 × 108 M− 1 and a binding capacity (B1) of 99.7 × 10− 8 M against human insulin for the high-affinity sites, indicating that the patient’s IA bound to insulin with low affinity and high binding capacity. He had no history of medication involving SH residues or supplements containing α-lipoic acid. Moreover, workup for endocrinological abnormality and autoimmune disease did not reveal any significant findings (Table 1). HLA-DRB1*04:06 was undetectable, and imaging studies of the head and abdomen showed no evidence of abnormalities.

The patient’s serum creatinine level was 2.17 mg/dl, and his estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 23.3 ml/min/1.73 m2. His arterial pH at 5:00 a.m. was 7.277, bicarbonate was 15.1 mEq/L, and base excess was − 10.7. After he was given a gradually increasing dose up to 3 g/day of sodium bicarbonate (split four times per day) for the purpose of correcting metabolic acidosis, his early morning glucose level was improved, concurrently bringing pH up to 7.4 (Fig. 1). Early morning hypoglycemia disappeared after he took 3 g/day of sodium bicarbonate and three meals plus snacks at night daily (1400 kcal/day) without any oral hypoglycemic agent or insulin. The patient was discharged in late March 2015 and continued on the same treatment.

Blood glucose levels in each eating pattern with or without alkali administration. Changes in plasma glucose levels were monitored at indicated times (0:00, 5:00, 7:00, 12:00, 14:00, 18:00, 21:00) in each eating pattern with or without administration of sodium bicarbonate. The inset shows plasma glucose level at 5:00 a.m. after raising the arterial pH to 7.4 by administration of sodium bicarbonate

After 9 months of follow-up with these treatments, the patient’s plasma glucose level at 5:00 a.m. was 96 mg/dl, and his arterial pH was 7.376. His immunoreactive insulin level had significantly decreased to 11.4 μIU/ml, even though the titer of IA remained high (> 50 U/ml). IA binding rate decreased to 42.1%. According to the Scatchard analysis, his IA shifted to higher affinity (K1 = 0.142 × 108 M− 1) and lower capacity (B1 = 0.969 × 10− 8 M) than his previous IA. During this follow-up period, he had no symptoms of hypoglycemia, his HbA1c levels were around 6.5%, and his eGFR did not change significantly. His daily plasma glucose levels ranged from 96 to 168 mg/dl.

Discussion and conclusions

We report a case of a patient with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia possibly caused by IA induced by insulin analogs that had lower affinity and higher capacity against insulin. IA are often detected in patients undergoing insulin treatment and rarely cause hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, because these antibodies usually have low capacity or high affinity. However, IA in IAS have lower affinity and higher capacity against insulin for the high-affinity sites than non-IAS antibodies [3]. Our patient’s case was analogous to IAS, whereas he produced IA that had lower affinity and higher capacity than those reported in typical IAS cases.

The widely accepted hypothesis for pathophysiology in IAS is as follows: massive volumes of insulin binding to IA causing postprandial hyperglycemia to persist and the release of insulin from immunocomplexes triggering hypoglycemia. However, the mechanism by which insulin binding occurs during the day and dissociation occurs in the early morning is unknown. The study of the effect of different pH values on insulin-binding capacity of IA showed that IA from patients with high titers of IA (> 40%) dissociated from insulin in lower pH, whereas this phenomenon was not observed in patients with low titers of IA (< 20%) [4]. In our patient, sodium bicarbonate was administered to correct the chronic metabolic acidosis, which then rectified the early morning glucose level. We propose that one possible mechanism for hypoglycemia in IAS is dissociation of IA from insulin in individuals with metabolic and/or respiratory acidosis in the early morning. However, many details of the overarching mechanism remain to be elucidated.

Small, frequent meals remain the first line of treatment for IAS, and patients with severe hypoglycemia require adjunct therapy, such as glucocorticoid therapy, which suppresses the production of antibodies and plasmapheresis, which reduce IA titers [5]. Recently, it was reported that hypoglycemia due to IAS was successfully managed with rituximab [6]. However, immunosuppressive therapies may be accompanied by adverse events, particularly infections, especially in the elderly. Our patient was successfully treated with sodium bicarbonate and frequent meals in small quantities.

We believe this to be the first published case report of a therapeutic approach to hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia resembling IAS, where blood pH seems to have had a pivotal role. Physicians should consider correction of acidosis using sodium bicarbonate as one option for the treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia associated with IA.

Abbreviations

- BIAsp 30:

-

Biphasic insulin aspart 30

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- IA:

-

Insulin antibody

- IAS:

-

Insulin autoimmune syndrome

References

Uchigata Y, Eguchi Y, Takayama-Hasumi S, Omori Y. Insulin autoimmune syndrome (Hirata disease): clinical features and epidemiology in Japan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;22:89–94.

Redmon JB, Nuttall FQ. Autoimmune hypoglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 1999;28:603–18.

Ishizuka T, Ogawa S, Mori T, Nako K, Nakamichi T, Oka Y, Ito S. Characteristics of the antibodies of two patients who developed daytime hyperglycemia and morning hypoglycemia because of insulin antibodies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;8:e21–3.

Ho LT, Wang LM, Chang TC, Fung TJ, Perng JC, Liu YF, et al. An in vitro approach to the kinetics of insulin antibodies in diabetic patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1999;46:65–72.

Lupsa BC, Chong AY, Cochran EK, Soos MA, Semple RK, Gorden P. Autoimmune forms of hypoglycemia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88:141–53.

Saxon DR, McDermott MT, Michels AW. Novel management of insulin autoimmune syndrome with rituximab and continuous glucose monitoring. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;101:1931–4.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff of Kanagawa Prefecture Shiomidai Hospital for their comments and technical assistance.

Funding

We received no funding for preparation of this article.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, because no datasets were generated or analyzed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. HA collected clinical data. YK and TY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics committee approval was required at our institution for this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobayashi, S., Amano, H., Kawaguchi, Y. et al. A novel treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia induced by insulin antibodies with alkali administration: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 79 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-1989-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-1989-8