Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis is a rare, necrotizing systemic vasculitis associated with asthma and hypereosinophilia. Its cause and pathophysiology are still being elucidated.

Case presentation

We report a case of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis in a 50-year-old Caucasian woman who presented with chest pain, dyspnea at rest, fever, and periorbital swelling. She was found to have significant hypereosinophilia and cardiac tamponade physiology. A biopsy confirmed extensive infiltration of both lungs and pericardium by eosinophils. She did not have any anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

Conclusions

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis diagnosis does not require the presence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-negative eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis may present with different clinical phenotypes, perhaps suggesting two distinct disease etiologies and distinct pathophysiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, is a rare, necrotizing systemic small-vessel vasculitis associated with asthma and hypereosinophilia [1]. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) established six criteria to aid in the clinical diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome based on extensive analysis of different patient presentations. These criteria include a diagnosis of: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia > 10%, (3) neuropathy (mono or poly), (4) non-fixed pulmonary infiltrates, (5) paranasal sinus abnormality, and (6) extravascular eosinophils [2]. The ACR determined that having at least four of the six criteria yields a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7% for Churg-Strauss syndrome [2]. These criteria are still used for the diagnosis of EGPA today.

We present an unusual case of a patient who met four of the six criteria for the diagnosis of EGPA, but also had several clinical phenotypes that have rarely been reported in the literature. We discuss the role that her anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) status may play in the pathophysiology of her disease.

Case presentation

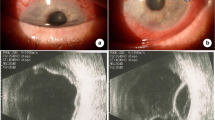

A 50-year-old Caucasian woman presented with chest pain, dyspnea at rest, fever, chills, night sweats, and left periorbital swelling (Fig. 1a). Her past medical history was significant for adult-onset asthma, hay fever, sinusitis, and recurrent nasal polyps. An initial transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a significant pericardial effusion (PE) with tamponade physiology (Fig. 1b). Pericardiocentesis was performed. She recovered well and was discharged. Ten days later, she presented with a syncopal episode. An echocardiogram showed a recurrent PE and a large pleural effusion. Thoracentesis was performed, and one liter of brown frothy fluid was removed, containing 77% eosinophils (Fig. 1c). A complete blood count revealed 45% eosinophilia. Antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi, Strongyloides, and ANCA were not present. Cytology, flow cytometry, and bone marrow aspirate showed no evidence of a hematopoietic malignancy. She underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for drainage of pericardial and pleural effusions. Subsequent biopsy of the lung and pericardium showed marked tissue infiltration by eosinophils (Fig. 1d, e). She was diagnosed as having EGPA, formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome. She was started on high-dose prednisone and her eosinophilia and clinical symptoms resolved. Cyclophosphamide was added before discharge to help prevent symptom recurrence.

Unusual clinical presentations of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-negative eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. a Our patient showing left periorbital swelling, possibly representing an orbital inflammatory pseudotumor. b The apical chamber view of a transthoracic echocardiogram shows a significant pericardial effusion. c Fluid drained from the pleural effusion contained 77% eosinophils. d Biopsied lung tissue shows marked infiltration by eosinophils, with eosinophils infiltrating the walls of small vessels, the submucosa of an adjacent small airway, and the interstitium. e Pericardial tissue shows significant infiltration by both eosinophils and plasma cells. d and e Hematoxylin and eosin, × 400. LV left ventricle, PE pericardial effusion, RV right ventricle

Discussion

Our patient presented with asthma, paranasal sinus abnormalities, hypereosinophilia, and extravascular eosinophils, and therefore met four of six criteria needed for the diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome [2]. Of interest, she did not present with any neuropathy or pulmonary infiltrates, which are the two other criteria used to classify EGPA and are some of the more common manifestations of this disease [2, 3]. Instead, she exhibited left periorbital swelling, probably representing a so-called orbital inflammatory pseudotumor formed by a localized mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate which, in our case, would be expected to also include numerous tissue eosinophils [4]. Very few cases of orbital inflammatory pseudotumors associated with EGPA have ever been described and may only present in less than 1% of all patients with the disease [4,5,6]. In addition, her cardiac tamponade was another unusual clinical presentation, reported in only ten other cases of EGPA [3, 7, 8]. Three of those studies were also able to confirm eosinophilic infiltration in the pericardium with biopsy, as we have demonstrated (Fig. 1e) [8]. Since the cause of EGPA is unknown and is difficult to study due to low disease prevalence (less than 1.4 per 100,000 adults), unusual case presentations like ours are an important step in helping to elucidate how different clinical phenotypes correlate with disease pathophysiology [3].

One hypothesis for why our patient had such an uncommon clinical presentation of her disease was because she lacked ANCA. Of interest, while EGPA is considered an ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis, only ~ 40 to 60% of patients with EGPA are ANCA-positive, as compared to up to 95% of patients with other small vessel vasculitides [3, 7, 9]. This is why the presence of ANCA is not a requirement for EGPA diagnosis. One study which stratified the clinical symptoms of patients with EGPA according to their ANCA status showed that ANCA-negative patients with EGPA are more likely to have fever and cardiac anomalies (more likely pericarditis and cardiomyopathy, less likely tamponade), whereas ANCA-positive patients more often had peripheral neuropathy, vasculitis, and renal involvement [7]. These findings have led several groups to hypothesize that the pathophysiology of ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative EGPA may be different. To generalize, it has been observed that ANCA-positive EGPA may have a more “vasculitic” phenotype, characterized by small vessel vasculitis, whereas ANCA-negative EGPA could be considered a more “eosinophilic” phenotype in which eosinophilic infiltration causes significant organ damage [7, 10]. This hypothesis will need further modeling and testing, but our unusual case would certainly lend support to this theory.

Conclusions

This case provides an example of an unusual clinical presentation of ANCA-negative EGPA with significant hypereosinophilia leading to multisystem organ damage and unusual disease manifestations including cardiac tamponade and periorbital swelling. Further studies and modeling will be needed to determine whether ANCA-negative EGPA and ANCA-positive EGPA truly define two distinct diseases with different pathophysiology.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- ANCA:

-

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- EGPA:

-

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- PE:

-

Pericardial effusion

References

Greco A, Rizzo MI, De Virgilio A, Gallo A, Fusconi M, Ruoppolo G, Altissimi G, De Vincentiis M. Churg-strauss syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:341–8.

Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Arend WP, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY. The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of churg-strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1094–100.

Noth I, Strek ME, Leff AR. Churg-strauss syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:587–94.

Takanashi T, Uchida S, Arita M, Okada M, Kashii S. Orbital inflammatory pseudotumor and ischemic vasculitis in churg-strauss syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1129–33.

Rothschild P-R, Pagnoux C, Seror R, Brézin AP, Delair E, Guillevin L. Ophthalmologic manifestations of systemic necrotizing vasculitides at diagnosis: a retrospective study of 1286 patients and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:507–14.

Ameli F, Phang KS, Masir N. Churg-Strauss syndrome presenting with conjunctival and eyelid masses: a case report. Med J Malaysia. 2011;66:517–9.

Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, Pagnoux C, Mouthon L, Jayne D, Blockmans D, Cordier J-F, Delaval P, Puechal X, Lauque D, Viallard J-F, Zoulim A, Guillevin L. French vasculitis study group: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the churg-strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:632–8.

Yano T, Ishimura S, Furukawa T, Koyama M, Tanaka M, Shimoshige S, Hashimoto A, Miura T. Cardiac tamponade leading to the diagnosis of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome): a case report and review of the literature. Heart Vessels. 2015;30:841–4.

Radice A, Bianchi L, Sinico RA. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies: methodological aspects and clinical significance in systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:487–95.

Gioffredi A, Maritati F, Oliva E, Buzio C. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: an overview. Front Immunol. 2014;5:549.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACK and JJR were involved in the preparation and writing of the manuscript and preparation of the figure. Both authors take full responsibility for its content. The patient, LLE, and JCH provided the original images used in the figure. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent for participation was obtained from the patient during in-patient hospital stay. Ethics review was not sought because this study met criteria for a “case report” which is not considered human subject research according to the Utah Institutional Review Board, and is therefore exempt from requiring ethics committee approval.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Keefe, A.C., Hymas, J.C., Emerson, L.L. et al. An atypical presentation of cardiac tamponade and periorbital swelling in a patient with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a case report. J Med Case Reports 11, 271 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1434-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1434-9