Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm is extremely rare. Although a majority of these cases have been associated with pregnancy, there have been recent reports and reviews of rare cases that were not directly associated with pregnancy. Transcatheter arterial embolization is considered to be an alternative therapy to surgery.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old Japanese woman, gravida 3 para 3, presented to our emergency room complaining of intermittent right flank pain. She had undergone a cesarean section 2 years previously, and had no history of abdominal trauma. On admission, her blood pressure was 115/78 mmHg, pulse 70 beats per minute, and hemoglobin concentration 9.8 g/dL. Abdominal ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography revealed a large retroperitoneal hematoma. Findings on three-dimensional computed tomography angiography suggested ruptured aneurysm of her right ovarian artery. A selective right ovarian artery angiogram revealed a tortuous aneurysm. Transcatheter arterial embolization using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate was performed. The aneurysm was successfully embolized, and her course after embolization was uneventful. She has remained symptom-free during 3 months of follow-up.

Conclusions

This was a very rare case of a patient who had a retroperitoneal hemorrhage originating from an ovarian artery aneurysm. A review of published case reports found that contrast-enhanced computed tomography with reconstruction images is an excellent imaging tool. Diagnostic angiography and subsequent transcatheter arterial embolization are thought to be very effective for this condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spontaneous rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm is extremely rare; only 25 cases have been reported in the English literature [1-24]. Although a majority of these cases were related to pregnancy and occurred during the peripartum or postpartum period, there have been recent reports and reviews of rare cases that were not directly associated with pregnancy [7,14,16,18-20,22]. Rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm leads to retroperitoneal hemorrhage and can be a life-threatening event. According to previously reported cases, life-saving treatment of a ruptured ovarian artery consists of surgery that includes ligation of the artery proximal and distal to the site of rupture. However, since the first report by King [9], transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) has emerged as an alternative therapy for patients who are hemodynamically stable. Here, we report the case of a patient with spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm who was successfully treated using TAE only. We also review the published case reports on this rarely occurring condition.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old Japanese woman, gravida 3 para 3, who had undergone cesarean section 2 years previously, presented to our emergency room with a 2-day history of intermittent right flank pain. She had no fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or cough. She had no history of abdominal trauma, and her past medical history and family history were not significant. She did not have hypertension or cardiovascular disease, and had not taken any anticoagulants. Her bowel and urinary habits were normal, and her menstrual periods were regular. Her last menstrual period had begun 2 days before the onset of right flank pain. On admission, her blood pressure was 115/78 mmHg, pulse 70 beats per minute, body temperature 36°C, and blood oxygen saturation 100%. She was found to be somewhat anemic, with a hemoglobin concentration of 9.8 g/dL and hematocrit of 28.2%. Her white blood cell count was elevated (13,900/mm3), and a urine pregnancy test was negative.

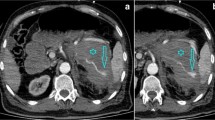

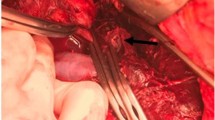

On physical examination, her abdomen was diffusely tender without muscle guarding. A pelvic examination revealed a small amount of menstrual discharge and a normal uterus and bilateral adnexae. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a large retroperitoneal hematoma surrounding her right kidney (Figure 1A). Emergent abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) was performed. Contrast-enhanced dynamic CT revealed a large retroperitoneal hematoma surrounding her right kidney with an enhancing round structure in the center of the hematoma in the arterial phase (Figure 1B). Although extravasation in the venous phase was not clear, findings on three-dimensional CT angiography were suggestive of a retroperitoneal hematoma due to rupture of an aneurysm of her right ovarian artery (Figure 1C), and no other responsible lesion was seen. A transfemoral angiography was performed for arterial embolization under a clinical diagnosis of bleeding from a right ovarian artery aneurysm. A selective angiogram of her right ovarian artery revealed a tortuous aneurysm near its origin from the aorta without obvious active extravasation (Figure 2A). A 2.1-Fr microcatheter (Tangent™; Boston Scientific, USA) was advanced into the orifice of the aneurysm, and 1mL of 16.7% N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) diluted in iodized oil (Lipiodol®; Guerbet Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was manually injected beyond the distal site of the aneurysm. A postembolization angiogram showed complete occlusion of the vessel (Figure 2B). No other aneurysm was found on three-dimensional CT and angiography.

Imaging tests for retroperitoneal hematoma. (A) Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a normal right kidney (left side, arrow) and a large hematoma in the retroperitoneum. A high-echoic lesion can be seen surrounding the right kidney (right side, arrowhead). (B) Arterial phase contrast-enhanced computed tomography image. A bright round structure (arrow) can be seen in the right retroperitoneal hematoma. (C) Three-dimensional computed tomography angiogram of the abdomen revealed a right ovarian artery aneurysm (arrow) overriding the right renal artery. Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; Rt., right; H, head, F, foot.

Angiograms before and after transcatheter arterial embolization. (A) Selective angiogram of the right ovarian artery showing several aneurysms (arrow) located near the origin from the aorta. (B) Angiogram obtained after N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate embolization showing successful embolization of the aneurysm. Note that the distal tortuous section of the right ovarian artery disappear (arrows).

One day after TAE, CT was performed, which showed that the hematoma had decreased in size, and there was no sign of extravasation. In addition, her hemoglobin and hematocrit were found to have dropped to 7.9 g/dL and 24.1%, respectively. She was administered iron for 4 days, with a subsequent increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit to 8.9g/dL and 25.6%, respectively. No other surgical intervention was needed, and her course after embolization was uneventful. She was discharged on the fifth hospital day, and has remained symptom-free during 3 months of follow-up.

Discussion

A retroperitoneal hematoma can be a life-threatening event, as well as a surgical emergency. Abdominal trauma, including iatrogenic injuries from surgical interventions such as inferior vena cava filter placement and arterial puncture, is the most common cause of retroperitoneal hemorrhage. In addition, a ruptured aortic or renal artery aneurysm, retroperitoneal tumors, and clotting disorders have been mentioned as the main causes of retroperitoneal hematoma [25].

The most common presenting symptom of retroperitoneal hematoma is acute abdominal or flank pain accompanied by clinical signs associated with bleeding. However, the clinical picture is often nonspecific, and the ruling out of acute abdomen, ureteral calculus, and pyelonephritis is needed. In addition, pregnant patients in the third trimester can be misdiagnosed with placental abruption or uterine rupture if they do not undergo an adequate imaging examination such as contrast-enhanced CT, although pregnancy is a relative contraindication to this procedure. The most common arterial sites for ruptured aneurysm in order of frequency during pregnancy are the aorta, cerebral arteries, splenic artery, renal artery, coronary artery, and ovarian artery [26].

Based on a MEDLINE search of the English language literature from 1963 to 2014, to the best of our knowledge, only 25 cases of spontaneous rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm have been reported [1-24]. Of these reported cases, 18 cases (72%) were associated with pregnancy (Table 1), and seven cases (28%) were not directly related to pregnancy (Table 2). The patients whose pregnancy and delivery history were available were all multigravida. The ages of the patients with pregnancy-related ruptured ovarian aneurysm ranged from 23 to 39 years (mean 33.6 and median 35 years), and the ages of the other patients ranged from 45 to 69 years (mean 51.5 and median 49.5 years). There seemed to be no difference regarding the side of the body where the ruptured aneurysm occurred. Among pregnancy-related patients, the aneurysm occurred on the left in eight and right in 10 cases; and among the other patients, on the left in five and right in three cases, including the present case. The majority of ruptures occurred during the postpartum period, which accounted for 14 out of 18 cases (78%). The onset of rupture occurred during the third trimester in two patients, who underwent cesarean section followed by ovarian artery ligation.

Because a ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm mostly occurs in women of high parity, the repeated hemodynamic and endocrine changes during pregnancy are thought to be the cause of arterial alterations that may lead to new aneurysm formation and/or weakening of pre-existing aneurysms [4,26]. In addition to the physiologic changes of pregnancy, hypertension might be a risk factor for rupture of ovarian artery aneurysm [18].

In earlier reported cases, the diagnosis was always obtained by exploratory laparotomy. Since Blachar et al. [12] first reported on the use of contrast-enhanced CT with reconstruction images, this imaging modality has been found highly effective for the preoperative diagnosis of ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm.

Of 17 cases published in 1990 or later, TAE was attempted as a treatment for ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm in 11 cases (64.7%), and the procedure was successful in nine cases, including ours. Because these patients had good outcomes after a minimally invasive procedure, TAE is currently considered to be the treatment of choice. The following embolic agents have been used in the previous reports; microcoils in five cases [9,11,17,19,21], gelatin sponge particles (GSPs) in one case [24], a combination of microcoils and GSP in one case [16], and NBCA was recently used in one case [23]. Our patient is the second case whose ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm was successfully treated using NBCA.

The mechanism of embolization by microcoil and GSP involves thrombin formation, which requires normal clotting function. However, NBCA occludes blood vessels because it polymerizes on contact with plasma, and therefore this method does not depend on the patient’s hemostatic capacity. Yonemitsu et al. evaluated the outcomes of TAE performed using microcoils, GSP, and NBCA in the setting of coagulopathy. They reported that the rate of primary hemostasis was significantly higher in patients undergoing NBCA compared to GSP, and the mean treatment time was significantly shorter for the NBCA procedure compared to the microcoil procedure [27]. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider NBCA as the embolic agent of choice for ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm, especially for critical patients in shock, who tend to have clotting problems due to coagulopathy. Because most patients with ovarian artery aneurysm are asymptomatic and rupture is an uncommon event, this condition may be underdiagnosed, and the risk factors for rupture have not yet been studied in depth. Additional case reports may help clarify the nature of ovarian artery aneurysms.

Conclusions

We presented a very rare case of a patient who had a retroperitoneal hemorrhage that originated from an ovarian artery aneurysm. Contrast-enhanced CT with reconstruction images has been found to be an excellent imaging tool. Diagnostic angiography combined with subsequent TAE during the same imaging session is thought to be a useful and highly effective alternative therapeutic procedure for this condition. Because ovarian arteries are potential sources of pelvic hemorrhage, these vessels should be routinely studied when imaging demonstrates the presence of a retroperitoneal hematoma, especially in multiparous women, whether or not they are pregnant.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GSP:

-

Gelatin sponge particle

- NBCA:

-

N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

- TAE:

-

Transcatheter arterial embolization

References

Caillouette JC, Owen HW. Postpartum spontaneous rupture of an ovarian-artery aneurysm. Obstet Gynecol. 1963;21:510–1.

Tsoutsoplides GC. Post-partum spontaneous rupture of a branch of the ovarian artery. Scott Med J. 1967;12:289–90.

Riley PM. Letter: Rupture of right ovarian artery aneurysm during delivery. S Afr Med J. 1975;49:729.

Burnett RA, Carfrae DC. Spontaneous rupture of ovarian artery aneurysm in the puerperium. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:744–50.

Jafari K, Saleh I. Postpartum spontaneous rupture of ovarian artery aneurysm. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:493–5.

Mojab K, Rodriguez J. Postpartum ovarian artery rupture with retroperitoneal hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;128:695–6.

Siu KF, Luk SL, Kung TM. Spontaneous rupture of the ovarian artery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1986;31:237–40.

Høgdall CK, Pedersen SJ, Ovlisen BO, Helgestrand UJ. Spontaneous rupture of an ovarian-artery aneurysm in the third trimester of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989;68:651–2.

King WL. Ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12:190–3.

Belfort MA, Simon T, Kirshon B, Howell JF. Ruptured ovarian artery aneurysm complicating a term vaginal delivery. South Med J. 1993;86:1073–4.

Guillem P, Bondue X, Chambon JP, Lemaitre L, Bounoua F. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma from rupture of an aneurysm of the ovarian artery following delivery. Ann Vasc Surg. 1999;13:445–8.

Blachar A, Bloom AI, Golan G, Venturero M, Bar-Ziv J. Case reports. Spiral CT imaging of a ruptured post-partum ovarian artery aneurysm. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:718–20.

Panoskaltsis T, Padwick M, Thomas JM, el Sayed T. Spontaneous rupture of ovarian arterial aneurysm in the antenatal period. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:718–9.

Manabe Y, Yoshioka K, Yanada J. Spontaneous rupture of a dissection of the left ovarian artery. J Med Invest. 2002;49:182–5.

Kale A, Akdeniz N, Erdemoglu M, Ozcan Y, Yalinkaya A. Spontaneous rupture of the ovarian artery following spontaneous vaginal birth. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1826–7.

Nakajo M, Ohkubo K, Fukukura Y, Nandate T. Embolization of spontaneous rupture of an aneurysm of the ovarian artery supplying the uterus with fibroids. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:887–90.

Poilblanc M, Winer N, Bouvier A, Gillard P, Boussion F, Aubé C, et al. Rupture of an aneurysm of the ovarian artery following delivery and endovascular treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:e7–8.

Chao L-W, Chen C-H. Spontaneous rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68:104–7.

Kirk JS, Deitch JS, Robinson HR, Haveson SP. Staged endovascular treatment of bilateral ruptured and intact ovarian artery aneurysms in a postmenopausal woman. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:208–10.

Tsai M-T, Lien W-C. Spontaneous rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:e7–9.

Mohammed N, Rai H, Koo B, Hoveyda F. Postpartum rupture of ovarian artery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:548–9.

Kodaira Y, Iwamura T, Hoshino H, Takahashi K, Kawahigashi Y, Matsumoto K. Spontaneous rupture of aneurysms of the ovarian artery at times remote from pregnancy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2014;81:101–5.

Wakimoto S, Hidaka N, Fukushima K, Kato K. Spontaneous post-partum rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm: A case report of successful embolization and a review of the published work. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014. doi:10.1111/jog.12535

Sakaguchi I, Ohba T, Ikeda O, Yamashita Y, Katabuchi H. Embolization for post-partum rupture of ovarian artery aneurysm: Case report and review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014. doi:10.1111/jog.12561

Phillips CK, Lepor H. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage caused by segmental arterial mediolysis. Rev Urol. 2006;8:36–40.

Barrett JM, Van Hooydonk JE, Boehm FH. Pregnancy-related rupture of arterial aneurysms. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:557–66.

Yonemitsu T, Kawai N, Sato M, Tanihata H, Takasaka I, Nakai M, et al. Evaluation of transcatheter arterial embolization with gelatin sponge particles, microcoils, and n-butyl cyanoacrylate for acute arterial bleeding in a coagulopathic condition. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1176–87.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Hideki Ota (Tohoku University) and Dr Tomonori Matsuura (Tohoku University) for their critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MT analyzed and interpreted the patient data, drafted the manuscript, and created the figures. TK, SI, HM, YM, TS, RM, NI, KA, YT, and HI performed the physical examinations and medical care. HR and AS performed the TAE procedure. TK, KA, HI, HR and AS provided valuable insight during manuscript preparation. KY supervised the entire case. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Toyoshima, M., Kudo, T., Igeta, S. et al. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage caused by rupture of an ovarian artery aneurysm: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 9, 84 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0553-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0553-4