Abstract

Introduction

Remote cerebellar hemorrhage is a rare complication of spinal surgery. Although loss of cerebrospinal fluid seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of this complication, the detailed mechanism of remote cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery remains unclear. We report the case of a patient with remote cerebellar hemorrhage following thoracic spinal surgery of an intradural extramedullary tumor and discuss this entity with reference to the literature.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old Japanese woman presented to our hospital with back pain, dysuria, and numbness of both legs. A neurological examination was performed, and imaging was performed with ordinary radiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography. Her magnetic resonance imaging scan showed an intradural extramedullary tumor at the T3 level. A tumor resection and T1-T5 pedicle screw fixation were performed. Twelve hours after spinal surgery, she complained of unexpected dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. A total of 850mL of serosanguineous fluid had been drained at that time, and drainage was stopped. An urgent brain computed tomography scan showed a cerebellar hemorrhage. She was treated conservatively, and was able to leave hospital six weeks after the initial operation, without any neurological deficits except for slight ataxia.

Conclusions

Remote cerebellar hemorrhage has to be suspected when unexpected neurological signs occur after spinal surgery. If an excessive amount of cerebrospinal fluid drains from the drainage tube after spinal surgery, drainage should be stopped.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remote cerebellar hemorrhage (RCH) following spinal surgery is a rare complication [1-25]. Although loss of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of this complication [1-25], the detailed mechanism of RCH after spinal surgery remains unclear. Here, we present a case of RCH after thoracic spinal surgery for an intradural extramedullary tumor, along with a review of previously reported cases and a discussion of the mechanism of RCH.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old Japanese woman, with no past medical history, presented to our institution with a one-year history of abdominal pain, a two-month history of back pain, numbness of both her legs, and a one-month history of dysuria. She initially reported abdominal pain and underwent extensive gastroenterological evaluation at another hospital, including an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which was unremarkable.

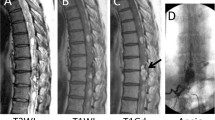

Her physical examination revealed no motor weakness and normal tendon reflexes. She felt hypoesthesia below the umbilicus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results demonstrated a large intradural extramedullary mass at the T3 level that was compressing her spinal cord from the ventral side (Figure 1).

Preoperative magnetic resonance images. Sagittal T1-weighted (a) and T2-weighted (b) magnetic resonance images of the thoracic spine, demonstrating an intradural extramedullary mass anterior to the spinal cord at the T3 level. The mass was iso-intense on T1-weighted imaging and T2-weighted imaging. Axial T1-weighted (c) and T2-weighted (d) magnetic resonance images show that the tumor seemed to be completely covered by the spinal cord.

The intradural extramedullary tumor was resected through a laminectomy of T2-T4 and a facetectomy of T2-T3 and T3-T4 in the prone position under transcranial motor-evoked potential (MEP) monitoring. As the tumor was completely covered by her spinal cord, it was surgically removed by rotation of the spinal cord using tenting of the dentate ligament. After tumor resection, the dura that adhered to the tumor was cauterized. A watertight repair of the dura was performed, using fibrin glue to avoid CSF leakage. A T1-T5 pedicle screw fixation was performed (Figure 2). Abnormal MEP signals were observed on her left leg during and after the tumor resection. A subfascial drain was put in place, with negative pressure. After she woke the motor power was weakened to grade three to four in her left knee and ankle. The total operating time was 4 hours 39 minutes, and the amount of bleeding was 108g. The histological diagnosis of the tumor was a meningioma.

Twelve hours after surgery, she developed nausea and confusion, and her clinical status deteriorated with loss of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale score of seven). A total of 850mL serosanguineous fluid had been drained at that time, and drainage was stopped. An emergency brain computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated an acute cerebellar hemorrhage in the superior folia of the cerebellar hemispheres (Figure 3). An MRI scan demonstrated a herniation of the cerebellar tonsils (Figure 4a, b). She was treated conservatively with anti-edema and antihypertensive drugs, and her clinical status improved gradually. After removal of the drain, there was no CSF leakage. The results of her follow-up CT scan performed one week later showed that her hematoma and brain edema were decreased. Twelve days later, the results of her follow-up MRI scan showed ascent of the cerebellum to the normal position (Figure 4c, d). At six weeks after surgery, she had slight ataxia and was discharged with a cane. At her one-year follow-up assessment, she had a normal neurological examination except for hypoesthesia of the right leg, and there was no CSF collection visible on her MRI scan.

Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging taken 13 hours and 12 days after spinal surgery. Sagittal T1-weighted (a) and T2-weighted (b) magnetic resonance images taken 13 hours after spinal surgery, demonstrating herniation of the cerebellar tonsils. Sagittal T1-weighted (c) and T2-weighted (d) magnetic resonance images taken 12 days after spinal surgery demonstrating ascent of the cerebellum to the normal position.

Discussion

Our case report has two characteristics. First, this case of thoracic meningioma that was located anterior to the spinal cord presented with a one-year history of undiagnosed abdominal pain. Lyons et al. [26] reported a similar case presenting as chronic abdominal pain. Second, although the tumor (which completely covered the spinal cord) was totally removed with a posterior surgical approach, our patient had some left lower extremity weakness postoperatively that improved gradually. A total resection of intradural extramedullary tumors located anterior to the spinal cord can be performed using an isolated posterior approach, with rotation of the spinal cord and tenting of the dentate ligament [27,28].

RCHs are rare and dramatic complications can follow spinal surgery. Prevention is important, because RCHs sometimes follow a fatal course. Sporadic cases have been published since the first description by Chadduck [4]. At the time of writing, 32 cases of RCH after spinal surgery have been reported in the English-language literature (Table 1). Including the present case, the 33 cases consisted of 23 women and 10 men, with an age range of 36 to 85 years (mean: 60.9 years). Initial surgery was performed at the lumbar spine in 21 cases, thoracic spine in six, cervical spine in five, and thoracolumbar spine in one. A dural tear during surgery was present in 26 cases, but was not noticed in seven cases. The neurological symptoms were detected between 0 and 192 hours (mean: 45.7 hours) after surgery. A total of 16 RCHs were resolved with conservative treatment, but three patients died or developed serious paresis [1-3,5,8,10,11,15,19,21-23]. However, in severe cases, emergency surgical intervention with ventricular drainage or posterior fossa craniotomy was needed. Cranial surgery was performed in 14 patients, nine of whom improved, and five died or had serious paresis after surgery [4,6,7,9,11-14,17,18,20,24,25].

RCH occurs in patients with a dural tear and CSF leakage, whether occult or not. It is thus believed that perioperative and/or postoperative CSF losses, leading to cranial hypotension, represent the main contributing factor in RCH [1,8,12]. The exact pathophysiology of RCH is still controversial. It is suggested that transient stretching and occlusion of superior cerebellar veins, resulting from downward cerebellar displacement under conditions of intracranial hypotension, may lead to cerebellar hemorrhagic infarction [8,20]. It is also suggested that cerebellar sag can directly cause tearing and bleeding of superior cerebellar veins [8]. Pallud et al. [20] hypothesized that RCH results primarily from superior cerebellar venous stretching and tearing, and that cerebellar infarction and swelling occur secondarily.

The loss of CSF should be restricted and controlled, because intracranial hypotension may be the initial cause of RCH. Closed wound suction drainage is recommended for spinal surgery, because a postoperative drain theoretically reduces the risk of infection and/or wound breakdown by decompressing the site of postoperative hematoma formation. However, if too much serosanguineous fluid drains postoperatively, stopping drainage or removing the drainage tube should be considered to prevent intracranial hypotension. Removal of the drain restores the normal CSF flow dynamics, allowing the cerebellum to resume its normal position [1]. Friedman et al. [8] described a 56-year-old woman with postoperative RCH whose headache resolved when suction drainage of the wound was discontinued. Thus, considering our case and the published literature, we suggest stopping drainage when RCH is suspected based on the patient’s complaints, including nausea and headache, and/or if an excessive amount of serosanguineous fluid has been drained postoperatively. This complication can be prevented by observing the amount of drainage fluid. If an excessive amount of fluid is drained, drainage should be stopped or converted to a gravity drain instead of a suction drain.

Conclusions

RCH is a rare postoperative complication of spinal surgery. RCH must be suspected when intracranial symptoms or unexpected neurological signs occur after spinal surgery. If an excessive amount of serosanguineous fluid is found coming from the drainage tube postoperatively, drainage should be stopped.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MEP:

-

Motor-evoked potential

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RCH:

-

Remote cerebellar hemorrhage

References

Andrews RT, Koci TM. Cerebellar herniation and infarction as a complication of an occult postoperative lumbar dural defect. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1312–5.

Calisaneller T, Yilmaz C, Ozger O, Caner H, Altinors N. Remote cerebellar haemorrhage after spinal surgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34:483–4.

Cevik B, Kirbas I, Cakir B, Akin K, Teksam M. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after lumbar spinal surgery. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:7–9.

Chadduck WM. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating cervical laminectomy. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:185–9.

Cornips EM, Staals J, Stavast A, Rijkers K, Van Oostenbrugge RJ. Fatal cerebral and cerebellar hemorrhagic infarction after thoracoscopic microdiscectomy: case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:276–9.

Enel D, Blamoutier A, Bacon P, Gentili ME. Spine surgery associated with fatal cerebellar haemorrhage. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:891–2.

Farag E, Abdou A, Riad I, Borsellino SR, Schubert A. Cerebellar hemorrhage caused by cerebrospinal fluid leak after spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:545–6.

Friedman JA, Ecker RD, Piepgras DG, Duke DA. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery: report of two cases and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1361–3.

Hashidate H, Kamimura M, Nakagawa H, Takahara K, Uchiyama S, Kato H. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spine surgery. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:150–4.

Hempelmann RG, Mater E. Remote intracranial parenchymal haematomas as complications of spinal surgery: presentation of three cases with minor or untypical symptoms. Eur Spine J. 2012;21 Suppl 4:S564–8.

Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Bydon A, Sciubba DM. Intracranial hemorrhage after spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:370–80.

Karaeminogullari O, Atalay B, Sahin O, Ozalay M, Demirors H, Tuncay C, et al. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after a spinal surgery complicated by dural tear: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57 Suppl 1:E215.

Khalatbari MR, Khalatbari I, Moharamzad Y. Intracranial hemorrhage following lumbar spine surgery. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:2091–6.

Khong P, Jerry Day M. Spontaneous cerebellar haemorrhage following lumbar fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1673–5.

Konya D, Ozgen S, Pamir MN. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery: case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:95–9.

Lee H-Y, Kim S-H, So K-Y. Seizure and delayed emergence from anesthesia resulting from remote cerebellar hemorrhage after lumbar spine surgery: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;63:270–3.

Mikawa Y, Watanabe R, Hino Y, Ishii R, Hirano K. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating cervical durotomy and revision C1-C2 fusion. Spine. 1994;19:1169–71.

Morofuji Y, Tsunoda K, Takeshita T, Hayashi K, Kitagawa N, Suyama K, et al. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage following thoracic spinal surgery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2009;49:117–9.

Nakazawa K, Yamamoto M, Murai K, Ishikawa S, Uchida T, Makita K. Delayed emergence from anesthesia resulting from cerebellar hemorrhage during cervical spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1470–1.

Pallud J, Belaïd H, Aldea S. Successful management of a life threatening cerebellar haemorrhage following spine surgery: a case report. Asian Spine J. 2009;3:32–4.

Takahashi Y, Nishida K, Ogawa K, Yasuhara T, Kumamoto S, Niimura T, et al. Multiple intracranial hemorrhages after cervical spinal surgery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2012;52:643–5.

Thomas G, Jayaram H, Cudlip S, Powell M. Supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage secondary to intracranial CSF hypotension following spinal surgery. Spine. 2002;27:E410–2.

Ulivieri S, Neri L, Oliveri G. Remote cerebellar haematoma after lumbar disc surgery. Case report. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80:219–20.

Yang K-H, Han JU, Jung J-K, Lee DI, Hwang S-I, Lim HK. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spine fixation misdiagnosed as a complication of narcotics use: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;60:54–6.

Yoo JC, Choi JJ, Lee DW, Lee S. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after intradural disc surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;53:118–20.

Lyons M, Windgassen E, Kinney C, Johnson D, Birch B, Boucher O. Thoracic meningioma masquerading as chronic abdominal pain. Turk Neurosurg. 2012;22:365–7.

Angevine PD, Kellner C, Haque RM, McCormick PC. Surgical management of ventral intradural spinal lesions. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:28–37.

Joaquim AF, Almeida JP, dos Santos MJ, Ghizoni E, de Oliveira E, Tedeschi H. Surgical management of intradural extramedullary tumors located anteriorly to the spinal cord. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:1150–3.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mamiko Kondo for her valuable assistance with the editing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Surgery was performed by TK. MS, TK, and NM were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. EA, TA, and YS supervised the whole work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, M., Kobayashi, T., Miyakoshi, N. et al. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage following thoracic spinal surgery of an intradural extramedullary tumor: a case report. J Med Case Reports 9, 68 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0541-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0541-8