Abstract

Background

The Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) recently published a chest CT classification system and Dutch Association for Radiology has announced Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) reporting and data system (CO-RADS) to provide guidelines to radiologists who interpret chest CT images of patients with suspected COVID-19 pneumonia. This study aimed to compare CO-RADS and RSNA classification with respect to their sensitivity and reliability for diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Results

A retrospective study assessed consecutive CT chest imaging of 359 COVID-19-positive patients. Three experienced radiologists who were aware of the final diagnosis of all patients, independently categorized each patient according to CO-RADS and RSNA classification. RT-PCR test performed within one week of chest CT scan was used as a reference standard for calculating sensitivity of each system. Kappa statistics and intraclass correlation coefficient were used to assess reliability of each system. The study group included 359 patients (180 men, 179 women; mean age, 45 ± 16.9 years). Considering combination of CO-RADS 3, 4 and 5 and combination of typical and indeterminate RSNA categories as positive predictors for COVID-19 diagnosis, the overall sensitivity was the same for both classification systems (72.7%). Applying both systems in moderate and severe/critically ill patients resulted in a significant increase in sensitivity (94.7% and 97.8%, respectively). The overall inter-reviewer agreement was excellent for CO-RADS (κ = 0.801), and good for RSNA classification (κ = 0.781).

Conclusion

CO-RADS and RSNA chest CT classification systems are comparable in diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia with similar sensitivity and reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Key points

-

CO-RADS and RSNA chest CT classification systems are comparable in diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia with similar sensitivity and reliability.

-

Considering combination of CO-RADS 3, 4 and 5 and combination of typical and indeterminate RSNA categories as positive predictors for COVID-19 diagnosis, the overall sensitivity was the same for both classification systems (72.7%).

-

Applying both systems in moderate and severe/critically ill patients resulted in a significant increase in sensitivity (94.7% and 97.8%, respectively).

-

The overall inter-reviewer agreement was excellent for CO-RADS (κ = 0.801) and good for the RSNA classification (κ = 0.781).

-

The CO-RADS had a better inter-reviewer agreement that may be attributed to greater familiarity with the CO-RADS system among radiologists due to its resemblance to other RAD systems.

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an acute infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The worldwide emergence of this novel virus was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020 by the World Health Organization and, since then, the world has been struggling to control its spread [2]. Among other methods, accurate, fast diagnostic testing is necessary to prevent potential viral dissemination and to reduce the disease fatality rate [3, 4].

Real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is considered the current gold-standard assessment for the diagnosis of COVID-19 [5]. However, RT-PCR is reported to have a low sensitivity with a considerable number of false-negative results, possibly necessitating that multiple tests be performed even up to five times to exclude the disease, despite the shortage of test kits in many regions all over the world [4, 6]. Moreover, it may take hours or even days for RT-PCR test results to be available [7, 8].

The full availability of CT machines and the short examination time make CT an ideal modality to take on an emerging role in the management of COVID-19 patients and to even act as an excellent alternative to RT-PCR in some circumstances [8], especially in countries with limited availability of RT-PCR testing [2]. CT could differentiate COVID-19 from other lung infections, especially viral ones [9]. Another advantage of CT is its ability to assess disease severity and progression [3, 10] as the volume of pneumonic involvement of the entire lung can suggest both [10, 11]. While the seventh Chinese Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan included chest CT imaging in the clinical diagnosis of patients with potential SARS-CoV-2 exposure, the American College of Radiology (ACR) has not recommended CT chest imaging for the initial diagnosis of patients suspected to have COVID-19, leaving it instead only indicated for specific situations [12, 13].

Several trials have been conducted to date to ascertain the proper and standardized reporting style of CT chest image findings in patients with suspected COVID-19 pulmonary involvement. The Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) chest CT classification system includes four categories: negative for pneumonia, atypical, indeterminate, and typical [14]. Another scoring system, the COVID-19 Reporting and Data System (CO-RADS) was developed by the Dutch Association for Radiology with grades ranging from 1 to 5 to suggest ascending disease probability according to the CT chest findings [15]. COVID-19 imaging reporting and data system (COVID-RADS) [16] is another described reporting system; however, it is less widely used.

For the application of any new classification system, it is essential to evaluate its validity and reliability. Few studies to date have been performed to establish the true value of the aforementioned systems as useful, reliable classification systems of chest CT examination findings in patients suspected to have COVID-19. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to compare CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system with respect to their sensitivity and reliability for the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

The institutional review board of Faculty of Human Medicine, Assiut University approved this study (approval no. 17300425; approved June 7, 2020) and waived the need to gather patients’ formal consent. The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient population

Between April 3, 2020 and May 15, 2020, we identified a total of 456 consecutively admitted patients with swab-confirmed COVID-19 in Assiut University Hospital. Eligible patients included those with swab-confirmed COVID-19 who underwent CT imaging of the chest within 12 h after admission, while the following were grounds for exclusion: (1) CT imaging performed prior to hospital admission (n = 27), (2) no CT imaging performed (n = 19), and (3) poor CT image quality (n = 51). The exclusion process resulted in a final sample consisted of 359 patients. The flowchart of our study population inclusion process is illustrated in Fig. 1. Our participants were classified into three groups based on disease severity as follows: the asymptomatic/mild group included patients with no symptoms or with mild symptoms and no imaging findings of pneumonia; the moderate group included patients with fever, respiratory symptoms, and imaging findings of pneumonia; and the severe/critically ill group included distressed patients with low oxygen saturation (SpO2 < 93% at rest) with or without the need for mechanical ventilation or patients in shock or with extrapulmonary organ failure necessitating intensive care unit admission [17].

CT imaging

All CT scans were performed within one week of RT-PCR. CT imaging was performed using a 16-channel CT scanner (Aquilion Lightning; Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). No contrast material was administered. Patients were scanned in the supine position, during breath-hold on full inspiration, from the lung apices down to the lung bases. The scanning parameters were as follows: tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current, 50 mA; rotation time, 0.5 s; slice thickness, 5 mm; matrix, 512 × 512; and breath-holding on full inspiration. The protocol was modified in pediatric patients (80 kV and 60 mAs). Reconstruction was carried out in the axial plane with a 1.0-mm slice thickness and 1.0-mm slice interval.

CT image analysis

All CT images were extracted from the Picture Archiving and Communication Systems and imported into a dedicated workstation (Vitrea® Advanced Visualization; Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN, USA) for image analysis. Three experienced radiologists (M.A, H.M.I, and S.H, with more than 10 years of experience in chest imaging) independently reviewed all CT images. They were blinded to previous CT reports as well as patients’ clinical data, but knew that all patients in the study were COVID-19-positives. Before the beginning of the study, the reviewers were provided with lecture-based and hands-on training that explained the CO-RADS and RSNA chest CT classification systems in detail. The CO-RADS includes five grades as follows: grade 5, very high level of suspicion; grade 4, high level of suspicion; grade 3, equivocal findings; grade 2, low level of suspicion; and grade 1: very low level of suspicion [15]. The CO-RADS grades are further illustrated in Table 1. The RSNA chest CT classification system includes four categories: typical, indeterminate, atypical, and negative (Table 2) [14].

The radiologists categorized the CT images of each patient according to the two classification systems at two different times with a one-month interval in between to diminish the radiologists’ memory bias. After independent categorization, inter- and intra-reviewer agreements were evaluated. In the case of a disagreement between reviewers, all parameters were discussed in detail until a final agreement could be reached at least 2 weeks after the second interpretation. The results of the consensus review were used to calculate the sensitivity of both systems.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are represented as numbers and percentages, and the statistical significance was calculated using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous data were expressed in the format of mean ± standard deviation. RT-PCR was used as a reference standard for calculating the sensitivity of CT for each reviewer; however, as we did not include cases with negative RT-PCT findings, specificity and predictive values were not calculated. The overall agreement was analyzed using the Fleiss kappa (κ) test. The κ values were interpreted as follows: 0–0.2, no agreement; 0.21–0.4, weak agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, good agreement; and 0.81–1.0, excellent agreement. Inter-reviewer agreement of the categories of each system was defined by the use of an intraclass correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

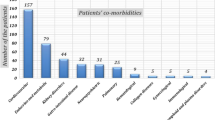

Patient characteristics

The final analysis included a total of 359 patients (180 men, 179 women; mean age, 45 ± 16.9 years; range, 1–90 years) who were COVID-19-positive confirmed by RT-PCR. The study participants’data are summarized in Table 3. With respect to disease severity, 96 (26.7%) patients were asymptomatic/had mild disease, 171 (47.6%) patients had moderate disease, and 92 (25.6%) patients had severe disease/were critically ill. Death occurred in 22 (6.1%) patients; all were categorized with a CO-RADS 5 and typical RSNA classification.

Assignment of CO-RADS and RSNA chest CT classification system categories

The categorization of patients based on CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system with regard to age is presented in Table 4. A highly statistically significant relationship was found between CT findings and age group (p < 0.001). Disease of CO-RADS 5 and typical RSNA classification was more commonly recorded among those aged older than 50 years (88.6%). On the other hand, patients younger than 15 years totaled only 2.5% of all participants and none had disease of CO-RADS 5 or the typical RSNA category; only one two-year-old child presented with disease of CO-RADS 4 and the indeterminate RSNA category.

The sensitivity of each classification system

Considering combined CO-RADS 3, 4 and 5 as a positive predictor for COVID-19 diagnosis, the sensitivity of CO-RADS was 9.4%, 94.7%, and 97.8%, in the asymptomatic/mild disease group, moderate disease group, and severe/critically ill disease group, respectively. Similar sensitivities were found when considering the typical and indeterminate RSNA categories together as a positive predictor for COVID-19 diagnosis (9.4%, 94.7%, and 97.8% in the asymptomatic/mild disease group, moderate disease group, and severe/critically ill disease group, respectively) (Table 5).

The reliability of each classification system

Table 6 shows the inter-reviewer agreement for the two classification systems stratified according to different categories. Among the reviewers, the overall inter-reviewer agreement was excellent for CO-RADS (κ = 0.801) and good for the RSNA chest CT classification system (κ = 0.781). Separately, the inter-reviewer agreement for individual diagnostic categories was excellent for CO-RAD 1 (κ = 0.924),CO-RAD-5 (κ = 0.888), the negative RSNA category (κ = 0.924), and the typical RSNA category (κ = 0.841); moderate for CO-RAD 4 (κ = 0.463); and weak for CO-RAD 2 (κ = 0.303), the indeterminate RSNA category (κ = 0.386), and the atypical RSNA category (κ = 0.380). CO-RAD 3 showed no agreement (κ = −0.017).

Table 7 shows the intra-reviewer agreement for the two systems stratified according to different categories and reviewers. The intra-reviewer agreement was excellent for all reviewers for CO-RADS 1, and 5, and the negative RSNA, and typical RSNA categories and good to excellent for CO-RADS 4 and the indeterminate RSNA category. No agreement was found for CO-RADS 2, or 3, or the atypical RSNA category.

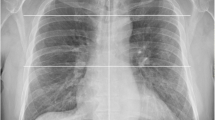

Representative cases from our study are illustrated in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

A 67-year-old man with positive RT-PCR findings for COVID-19. a–d Noncontrast axial CT images of the chest show bilateral, multifocal peripheral ground-glass opacities with superimposed interlobular septal thickening and intralobular lines are visible, giving the appearance of “crazy-paving”. This is in keeping with his CO-RADS 5 and typical RSNA classification

Discussion

The diagnosis of COVID-19, especially mild forms of the disease, constitutes one of the major challenges in clinical practice nowadays. CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system are the results of efforts made to create a uniform CT-based classification for the diagnosis of COVID-19. However, global studies of these classification systems are still limited in number. The current study is an attempt to assess and compare the sensitivity and reliability of these two systems.

The overall results demonstrated that both systems are comparable to one another, with similar sensitivity values. Considering the combination of CO-RADS 3, 4 and 5 and the combination of the typical and indeterminate RSNA categories, respectively, as positive predictors for COVID-19 diagnosis, the overall sensitivity was the same for both classification systems (72.7%). Meanwhile, the sensitivity significantly increased for both systems when excluding the asymptomatic/mild patients and considering only moderate (sensitivity = 94.7%) and severe/critically ill patients (sensitivity = 97.8%); this is not surprising, taking into account that the sensitivity depends on CT imaging features, which have been considerably proven in several recent studies [6, 18,19,20,21,22], while CT has been confirmed to be a reliable imaging approach for the evaluation of COVID-19. Our data are congruent with the results mentioned in previous research [15, 23,24,25,26,27,28], which suggested that the CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system performed very well in predicting COVID-19 in patients with moderate to severe symptoms. Notably, a recent meta-analysis published by Kwee et al. [29] concluded that COVID-19 infection frequency was higher in patients categorized with higher CO-RADS and RSNA classification categories.

A remarkable finding in our study was the high proportion of false-negative results (n = 100 patients; 27.9%); of these, 98 patients were categorized as CO-RADS 1 and 2 and RSNA classification categories negative and a typical. This high proportion of false-negative results was due to the fact that CT chest imaging was performed early in the disease course. Comparable results were reported by Prokop et al. [15] and Bernheim et al. [30].

Although higher categories had high sensitivity for both classification systems, false-negative results were high, too. Therefore, lower categories could not exclude COVID-19. These results agree with the recent meta-analysis published by Kwee et al. [29], which reported that CO-RADS 1 and 2 and RSNA classification categories negative and a typical do not exclude COVID-19.

The reliability is crucial for evaluating a new classification system. An analysis of our results demonstrated that CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system had comparable overall good to excellent inter-reviewer agreement, with a higher level of agreement achieved for CO-RADS (κ = 0.801) than for the RSNA chest CT classification system (κ = 0.781). Meanwhile, the intra-reviewer agreement was excellent for both systems, although it tended to be lower for CO-RADS 2 and 3 and for the indeterminate and atypical RSNA categories. The reason for the lower agreement in the intermediate categories of both systems may be largely related to the fact that all the patients were actually COVID-19-positives, while those categories are meant for alternative diagnoses. However, if there were real lobar pneumonias or "tree in bud" patterns, the agreement would have been higher. Our results are in line with those of several previous studies [15, 23, 28, 31, 32]. Prokop et al. [15] conducted the first study that investigated the consistency of CO-RADS and reported a reasonable level of moderate intra-reviewer agreement (κ = 0.47), with the highest agreement noted for CO-RADS 1 (κ = 0.58) and 5 (κ = 0.68). A recent study published by Bellini et al. [23] indicated a moderate level of overall agreement was obtained for CO-RADS (κ = 0.43), with less agreement achieved for the intermediate (grades 2–4) CO-RADS categories than for CO-RADS 1 and 5. Separately, in a study conducted by Ciccarese et al. [28], two readers evaluated 460 patients according to the RSNA chest CT classification system and achieved a good level of inter-reviewer agreement for the typical and negative categories and a fair level of inter-reviewer agreement for the indeterminate and atypical categories (κ = 0.5). Another study [31] investigated inter-reviewer agreement for the RSNA chest CT classification system and reported excellent agreement for typical, atypical, and negative RSNA categories and good agreement for the indeterminate category. A more recent study published by Inui et al. [32] reported good inter-reviewer agreement for CO-RADS (κ = 0.62) and the RSNA classification (κ = 0.63).

Regarding patient demographics, we found that pulmonary changes are less likely to occur at a young age. Among nine study participants younger than 15 years, only one patient, a two-year-old male child, developed pneumonia (CO-RADS 4 and indeterminate RSNA category). This finding is unsurprising given that COVID-19 has a predominantly mild presentation and a good prognosis in children, with rare occurrences of death. A study published by Zheng et al. [33] concluded that children with COVID-19 similarly had a more favorable clinical presentation than adults; however, those younger than three years old were more susceptible to developing severe illness. In our study, most adults presented with high CO-RADS grades and the typical RSNA category. This finding agrees with the well-known conclusion that old age is a predisposing factor for COVID-19 pneumonia [34]. An interesting finding in our study was that all death cases occurred in patients with CO-RADS 5 and the typical RSNA category. This finding might reassure some about the patient outcome for those with results below CO-RADS 5 and the typical RSNA category. However, identifying those with lower scores is still important in facilitating the isolation of infected patients.

In summary, based on these findings, which resemble those of the aforementioned published studies, we found that both systems are comparable, with similar sensitivity and reliability values, and suggest that using either system will yield the same results. Along these lines, both systems performed well when applied in moderate and severe/critically ill patients. However, some limitations are present in our study. First, this study was retrospective and performed in a single center. Second, our study included only the first CT chest performed around the time of admission irrespective of the number of days that had elapsed since the appearance of symptoms. Third, the specificity and predictive values of CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system for the diagnosis of COVID-19 were not established, as we did not include COVID-19 negative-patients in our analysis. Fourth, we did not consider the impact of comorbidity factors on the sensitivity of CO-RADS and RSNA classification. Fifth, the radiologists who reviewed the CT images known that all patients participating in the study were positive for COVID-19, which may be a source of bias. Finally, many clinicians are still unfamiliar with the CO-RADS and RSNA CT classification system and might misunderstand these schemes as simple indicators of disease severity unless the CT-severity score is stated in the report.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results support that CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification systems are comparable to one another in the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia with similar sensitivity and reliability values. Applying these systems in patients with moderate and severe symptoms will significantly improve their sensitivity for diagnosing COVID-19 pneumonia. However, CO-RADS had a better inter-reviewer agreement that may be attributed to greater familiarity with the CO-RADS system among radiologists due to its resemblance to other RAD systems.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CO-RADS:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019 reporting and data system

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GGO:

-

Ground-glass opacities

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficien

- IRB:

-

Institutional review boards

- RSNA:

-

Radiological Society of North America

- RT-PCR:

-

Real-time reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W et al (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med 382:727–733

Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB et al (2020) The role of chest imaging in patient management during the COVID-19 pndemic: a multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner society. Radiology 296:172–180

Fan L, Liu SY (2020) CT and COVID-19: Chinese experience and recommendations concerning detection, staging and follow-up. Eur Radiol 30:5214–5216

Kanne JP, Little BP, Chung JH et al (2020) Essentials for radiologists on COVID-19: an update-radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology 296:E113–E114

Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M et al (2020) Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 25:1–8

Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W et al (2020) Chest CT for typical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: relationship to negative rt-PCR testing. Radiology 296:E41–E45

Li Y, Xia L (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): role of chest CT in diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol 214:1280–1286

Long C, Xu H, Shen Q et al (2020) Diagnosis of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): rRT-PCR or CT? Eur J Radiol 126:108961

Choi W, My T, Tran L et al (2020) Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT. Radiology 1:1–13

Yang R, Li X, Liu H et al (2020) Chest CT severity score: an imaging tool for assessing severe COVID-19. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2:e200047

Zhou Z, Guo D, Li C et al (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019: initial chest CT findings. Eur Radiol 30:4398–4406

Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan (Provisional 7th Edition) [Internet]. virus-treatment-plan-7/?lang=en

ACR Recommendations for the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography ( CT ) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. In: 11 Mar. 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed 31 Aug 2020

Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S et al (2020) Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2:p.e200152.

Prokop M, Van Everdingen W, Van Rees VT et al (2020) CO-RADS: a categorical CT assessment scheme for patients suspected of having COVID-19-definition and evaluation. Radiology 296:E97–E104

Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) imaging reporting and data system (COVID-RADS) and common lexicon: a proposal based on the imaging data of 37 studies. Eur Radiol 30:4930–4942

Wang YC, Luo H, Liu S et al (2020) Dynamic evolution of COVID-19 on chest computed tomography: experience from Jiangsu Province of China. Eur Radiol 30:6194–6203

Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H et al (2020) Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology 296:E32–E40

Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X et al (2020) CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-NCoV). Radiology 295:202–207

Pan F, Ye T, Sun P et al (2020) Time course of lung changes at chest CT during recovery from Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Radiology 295:715–721

Bai HX, Hsieh B, Xiong Z et al (2020) Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from Non-COVID-19 viral pneumonia at chest CT. Radiology 296:E46–E54

Xu B, Xing Y, Peng J et al (2020) Chest CT for detecting COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Eur Radiol 30:5720–5727

Bellini D, Panvini N, Rengo M et al (2020) Diagnostic accuracy and interobserver variability of CO-RADS in patients with suspected coronavirus disease-2019: a multireader validation study. Eur Radiol 66:1–9

Lessmann N, Sánchez CI, Beenen L et al (2020) Automated assessment of CO-RADS and chest CT severity scores in patients with suspected COVID-19 using artificial intelligence. Radiology 298:239

De Smet K, De Smet D, Ryckaert T et al (2021) Diagnostic performance of chest CT for SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals with or without COVID-19 symptoms. Radiology 298:E30–E37

De Smet K, De Smet D, Demedts I et al (2020) Diagnostic power of chest CT for COVID-19: to screen or not to screen. medRxiv

Fujioka T, Takahashi M, Mori M et al (2020) Evaluation of the usefulness of CO-RADS for chest CT in patients suspected of having COVID-19. Diagnostics 10:608

Ciccarese F, Coppola F, Spinelli D et al (2020) Diagnostic accuracy of North America Expert Consensus Statement on reporting CT findings in patients with suspected COVID-19 infection: an Italian Single Center Experience. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2:e200312

Kwee RM, Adams HJ, Kwee TC (2021) Diagnostic performance of CO-RADS and the RSNA classification system in evaluating COVID-19 at Chest CT: a meta-analysis. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 3(1):e200510. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2021200510

Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M et al (2020) Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology 295:685–691

Byrne D, O’Neill SB, Müller NL et al (2020) RSNA expert consensus statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19: interobserver agreement between chest radiologists. Can Assoc Radiol J 0846537120938328

Inui S, Kurokawa R, Nakai Y et al (2020) Comparison of chest CT grading systems in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology Cardiothorac Imaging 2(6):e200492. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.202020049233

Zheng F, Liao C, Fan Q et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of children with coronavirus disease 2019 in Hubei, China. Curr Med Sci 40:275–280

Shi H, Han X, Jiang N et al (2020) Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:425–434

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all staff members and colleagues in the Radiology Department-Assiut University, for their helpful cooperation.

Funding

The authors declare that this work has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor of integrity of the entire study— (MB and MA). Study concepts and design—(MB, MA, and SH). Literature research—(HI, SB, MZ, NM). Clinical studies— (MA, IM, SA, AE, HY, WS, and WM). Experimental studies/data analysis—(MB, MA, IM, SH, and HI). Statistical analysis—(MB and MA). Manuscript preparation— (MB and MA). Manuscript editing—(MB). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board’s approval was obtained (approval no. 17300425).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Statistics and biometry

The corresponding author has great statistical expertise.

Methodology

(1) Retrospective; (2) Diagnostic or prognostic study; (3) Performed at single centre.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Tawab, M., Basha, M.A.A., Mohamed, I.A.I. et al. Comparison of the CO-RADS and the RSNA chest CT classification system concerning sensitivity and reliability for the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. Insights Imaging 12, 55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-021-00998-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-021-00998-4