Abstract

Background

The molecular mechanisms underlying sex determination and differentiation in animals are incredibly diverse. The Dmrt (doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor) gene family is an evolutionary ancient group of transcription factors dating to the ancestor of metazoans that are, in part, involved in sex determination and differentiation in numerous bilaterian animals and thus represents a potentially conserved mechanism for differentiating males and females dating to the protostome-deuterostome ancestor. Recently, the diversity of this gene family throughout animals has been described, but the expression and potential function for Dmrt genes is not well understood outside the bilaterians.

Results

Here, we report sex- and developmental-specific expression of all 11 Dmrts in the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Nine out of the eleven Dmrts showed significant differences in developmental expression, with the highest expression typically in the adult stage and, in some cases, with little or no expression measured during embryogenesis. When expression was compared in females and males, seven of the eleven Dmrt genes had significant differences in expression with higher expression in males than in females for six of the genes. Lastly, expressions of two Dmrt genes with differential expression in each sex are located in the mesenteries and into the pharynx in polyps.

Conclusions

Our results show that the phylogenetic diversity of Dmrt genes in N. vectensis is matched by an equally diverse pattern of expression during development and in each sex. This dynamic expression suggests multiple functions for Dmrt genes likely present in early diverging metazoans. Detailed functional analyses of individual genes will inform hypotheses regarding the antiquity of function for these transcription factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The pathways involved in metazoan sex determination are diverse including transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional modifications, and hormone synthesis. However, distantly related metazoan phyla (e.g., arthropods, nematodes, and chordates) utilize a member of the doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor (Dmrt) family to regulate sexual determination and/or the development of sexual dimorphism [1,2]. This gene family is defined by its presence of a highly conserved DNA binding motif, the DM domain, which is characterized by cysteine-rich, interlaced zinc fingers [3]. Additionally, some Dmrt genes have an additional conserved region termed the DMA domain, which may be involved in neurogenesis [4,5], although the specific functions are unknown.

In bilaterians, one or more DMRT proteins play a role in the development of male-specific characteristics [6-11]. Broadly, Dmrt genes contribute towards sex-specific characteristics and can promote the phenotypes of either males or females. Evidence from various species has suggested that two characteristics of Dmrt genes correlate with sex-biased expression: loss or absence of the DMA domain and differential splicing. For example, in Drosophila melanogaster, the Dmrt gene called doublesex (dsx) is named because it plays a role in determining both males and females [12]. dsx from Drosophila (and other insects) lacks a DMA domain (like DMRT1 in mammals and mab-3 in C. elegans) and undergoes differential splicing in each sex. Male and female fruit flies express dsx transcripts but produce different isoforms via alternate splicing (DSXM and DSXF) [12]. Splicing of Dmrt transcripts appears to be common in many animals; however, the function of splice variants outside of sex determination in studied insects remains largely unstudied [13].

Given the variation among bilaterian animals in the function of Dmrt genes, including sex determination and neurogenesis, data from outgroups to the bilaterians (e.g., ctenophores, cnidarians) are needed to clarify potential ancestral functions in the animal lineage. In the reef building coral Acropora millepora, one Dmrt gene (named DM 1, evolutionarily related to other Dmrt genes from cnidarians and Trichoplax and most closely related to Nematostella vectensis Dmrt A) [14] was highly expressed in the tips of adult corals during the reproductive season [15]. A. millepora is a simultaneous hermaphrodite; thus, increased expression of this single Dmrt gene could not be assigned to a particular sex. AmDM 1 contained a DMA domain and the transcript showed two splice variants, suggesting a potential role for post-transcriptional modification like that observed for dsx in D. melanogaster [15]. Subsequent to this study, gene discovery and phylogenetic analyses from A. millepora have shown that this coral species contains at least five additional Dmrt genes that have not yet been characterized [14]. Dmrt genes have been identified in other early diverging phyla [14,16], but expression or function has not been characterized.

N. vectensis is a cnidarian amenable to studying Dmrt genes in development, sexual determination, and/or differentiation in an early diverging species due to accessibility of developmental stages and adult gonochorism [17]. N. vectensis has 11 Dmrt genes [5,14], the most of any animal species yet described, which have generally unclear orthology to bilaterian Dmrt genes suggesting independent expansion of this gene family in cnidarians. Switching of sexes or hermaphroditism has not been documented in this species suggesting that sex determination likely has a genetic component [17]. In adult females, oocytes develop within the mesenteries, so that all stages of oogenesis can potentially be present [18]. In adult males, spermary development occurs within the mesenteries in tight bundles [19].

We report the protein models and domain architecture for the 11 N. vectensis proteins. To begin to characterize the role of Dmrt genes in N. vectensis, gene expression was determined over a developmental series and in sexually mature males and females. We found significant differences in gene expression of Dmrt genes between males and females, consistent with a potential role in sex determination or differentiation. Additionally, we found differences in expression during development. This report presents the first evidence of differences in Dmrt gene expression between females and males in a cnidarian.

Methods

Gene and protein models

The 11 Dmrts which were previously identified in Bellefroid et al. 2013 [16] and Wexler et al. [14] were blasted using blastn or tblastn against the full DNA sequence scaffold identified on the Joint Genome Institute genome portal (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Nemve1/Nemve1.info.html). These sequences were then further analyzed using HMMER (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD, USA) to identify protein domains [20]. For full JGI gene models, see Additional file 1: Table S1.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

To confirm the predicted sequences from N. vectensis as well as to generate plasmids for qPCR analysis and in situ hybridization (described below), we amplified, cloned, and sequenced portions of each predicted transcript (primers designed with Primer3 (Genomics at Estonian Biocentre, Estonia), primer sequences listed in Additional file 2: Table S2) from cDNA. For characterization of sex-specific expression patterns, RNA was extracted from three biological replicates of pooled samples of males and females using the Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with on-column DNAse digestion, as described previously [21,22]. For the developmental time series, RNA was extracted from three biological replicates from four developmental stages: embryo (0.5 to 1 days post fertilization (dpf)), early planula (3 to 4 dpf), late planula (7 to 11 dpf), and juvenile polyp (8 to 23 dpf). From the total RNA, cDNA was synthesized with the Iscript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using 1.5 μg of RNA per 30 μl reaction.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR)

Oligonucleotide primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) were designed to amplify each N. vectensis Dmrt gene. Primers were 20 to 23 nt, with a GC content of 40 to 60%, in most cases, spanned a large intron, and produced amplicons with minimal predicted secondary structure (m-fold, [23]). A standard curve was constructed from serially diluted plasmids containing the amplicon of interest for each gene. The standard curve was used in qPCR reactions to quantify amplification efficiency and to calculate the number of molecules per reaction as in [21]. qPCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and reactions were run using a MyCycler Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad).

Standards and experimental samples were run on a single plate. The PCR mixture consisted of 11.5 μl of molecular biology grade distilled water, 12.5 μl of IQ SYBR Green Supermix, 0.5 μl of 10 μM gene-specific primers, and 0.5 μl of cDNA. PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 64°C for 45 s. After 40 cycles, the PCR products from each reaction were subjected to melt curve analysis to ensure that only a single product was amplified. The number of molecules per microliter for each gene was calculated by comparing the threshold cycle (Ct) from the sample with the standard curve.

Expression data for developmental stages was standardized by total RNA input into the cDNA synthesis reaction. Expression data for the comparison of males and females was standardized to a constitutively expressed heat shock protein, which served as a control gene. Expression was compared among developmental stages (embryo through juvenile) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test as a post-hoc test. Expression differences between sexes were statistically compared with a t-test.

In situ hybridization of adult polyps

Results from qPCR indicated that a number of Dmrt genes were differentially expressed between male and female anemones. Expression of two of these Dmrt genes (E and G) was determined with in situ hybridization using 8 to 10 tentacle adults following standard protocols [24,25]. Probes were synthesized with the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using the cloned sequences used for the plasmid curve for qPCR analysis.

Results and discussion

Protein domain organization in N. vectensis DMRTs

Comparing the 11 N. vectensis proteins, NvDMRT A to H all have DMA domains (Figure 1). Additionally. NvDMRT A and E have a proline-rich domain, while NvDMRT F has a zf-ribbon-3 domain present. The full coding sequence for all N. vectensis Dmrt genes has not yet been sequence confirmed (e.g., NvDmrt K) resulting in unreliable gene models; thus, additional domains may be identified when these genes are verified. These results confirm that cnidarians have DMRT proteins both with and without a DMA domain, like previously reported in protostomes and deuterostomes, further suggesting that the domain diversity in bilaterian DMRTs dates to early animal evolution.

Protein/gene models of the N. vectensis Dmrts. NvDmrt A-H have DMA domains present. Additionally, a proline-rich domain is found in NvDmrt A and NvDmrt E, and a zf-ribbon-3 domain in NvDmrt F. The role of these additional domains in N. vectensis is currently unknown. NvDmrt, Nematostella vectensis doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor.

Differential expression of Dmrts: developmental stages

Previous research reported the developmental expression of one of the 11 N. vectensis Dmrt genes, NvDmrt B. NvDmrt B is expressed in a “salt-and-pepper” pattern during embryogenesis in presumptive neuronal cells, and morpholino-based knockdown of this gene resulted in a reduction in Elav-1 positive neurons [5,16]. This result is consistent with the role of Dmrt genes in neurogenesis at the cnidarian-bilaterian ancestor but does not address the other potential functions of the diverse suite of Dmrt genes in cnidarians. One component of gene function is the timing of expression during development. Our quantitative comparisons of Dmrt gene expression for all eleven genes over a coarse development series showed a significant difference in expression for eight out of the eleven Dmrt genes where different stages had peak expression (Figure 2). For example, NvDmrt E showed the highest expression at the pooled embryo stage and in female adults, with modest expression in the other developmental stages (Figure 2). NvDmrt A showed relatively high expression in all developmental stages except the pooled embryo stage and the adults (males and females). Together, these data show that Dmrt genes in N. vectensis have differential expression during development.

Quantitative PCR results for expression of 11 NvDmrt genes over a developmental series (Em = embryo, EL = early larvae, LL = late larva, Juv = Juvenile) and between males (M) and females (F). The developmental series results from statistical comparisons are shown with the P value, and letters above bars indicate statistical grouping based on post-hoc comparisons. Significant differences in gene expression between males are females are indicated with an asterisk (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001). NS, no significant difference.

Differential expression of Dmrts: females and males

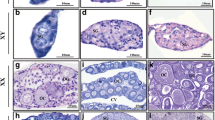

Due to the function of Dmrts in sex determination and differentiation in various bilaterian animals and our observation that many Dmrt genes have higher expression at the adult stage, we compared expression of all 11 genes in sexual mature female and male anemones. Seven of the eleven Dmrt gene tested had significant differences in expression between females and males, all higher in males with the exception of NvDmrt E (Figure 2). NvDmrt E had considerably higher expression (>78 fold change) in females with low expression in males. Males had higher expression in the six other Dmrts, with NvDmrt K having the highest expression (>24 fold change) (Figure 2). To investigate if two of these DMRT genes with differences in expression based on sex (E and G) were expressed in regions potentially involved in gamete development, we determined spatial expression with in situ hybridization using 8 to 10 tentacle adults. Expression for each gene was located throughout the subpharyngeal mesenteries and extended into the pharynx (Figure 3). Efforts to determine cell-specific expression or sex of the polyps with histology were not successful. Thus, while these data suggest that these genes are expressed in the gametogenic regions of the polyp, we cannot discern the likelihood if they are involved in a sex- or gamete-specific process. Further work comparing expression of these and other Dmrt genes with other gamete-specific markers (e.g., SYC1 and 3 [26] or GCS1 [27]) would be informative. Additional in situ hybridizations will need to be conducted on adults as well as developmental time series to better elucidate the spatial expression of these genes.

Spatial expression of two Dmrt genes in young adult polyps by RNA in situ hybridization. Staining of (A) NvDmrt E and (B) NvDmrt G are found throughout the mesenteries of the polyp. Black arrows denote the subpharyngeal mesenteries, while the white arrows denote pharyngeal region. Scale bar = 0.5 mm.

Conclusions

Previous research has shown that the Dmrt gene family evolved early in the metazoan lineage, likely in the ancestor of all animals due to the presence of these genes in all phyla but not in unicellular outgroups [14]. We show here that for the cnidarian N. vectensis, which has the most Dmrt genes for any species yet characterized, the diversity of genes is accompanied by an equally diverse pattern of expression during development and in each sex. Dmrt genes from various species commonly have splice variants that impact the function of the translated proteins. In our studies, we did not detect any splice variants for Nematostella Dmrts nor were any reported in previous studies that annotated Dmrts from this species. Our targeted PCR and cloning approach was based on genome annotations, not high-throughput sequencing; thus, we cannot rule out the possibility of splice variants. Thus, the expression shown in this study may be due to isoform specificity and may not represent all the isoforms including those that may be critical for sex determination. Significant differences in the expression of particular Dmrt genes between females and males may serve as useful biomarkers for determining sex of individuals, both in the laboratory and in field collections of natural populations.

Abbreviations

- Dmrt :

-

doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor

- Nv:

-

Nematostella vectensis

References

Angelopoulou R, Lavranos G, Manolakou P. Sex determination strategies in 2012: towards a common regulatory model? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:13. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-10-13.

Kopp A. Dmrt genes in the development and evolution of sexual dimorphism. Trends Genet. 2012;28(4):175–84.

Erdman SE, Burtis KC. The Drosophila doublesex proteins share a novel zinc finger related DNA binding domain. EMBO J. 1993;12(2):527–35.

Huang X, Hong CS, O’Donnell M, Saint-Jeannet JP. The doublesex-related gene, XDmrt4, is required for neurogenesis in the olfactory system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(32):11349–54.

Parlier D, Moers V, Van Campenhout C, Preillon J, Leclere L, Saulnier A, et al. The Xenopus doublesex-related gene Dmrt5 is required for olfactory placode neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 2013;373(1):39–52.

Shoemaker C, Ramsey M, Queen J, Crews D. Expression of Sox9, Mis, and Dmrt1 in the gonad of a species with temperature-dependent sex determination. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(4):1055–63.

Raymond CS, Murphy Mark W, O’Sullivan G, Bardwell Vivian J, Zarkower D. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Gene Dev. 2000;14:2587–95.

Nakamoto M, Muramatsu S, Yoshida S, Matsuda M, Nagahama Y, Shibata N. Gonadal sex differentiation and expression of Sox9a2, Dmrt1, and Foxl2 in Oryzias luzonensis. Genesis. 2009;47(5):289–99.

Marchand O, Govoroun M, D’Cotta H, McMeel O, Lareyre JJ, Bernot A, et al. DMRT1 expression during gonadal differentiation and spermatogenesis in the rainbow trout. Oncorhynchus mykiss. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1493(1–2):180–7.

Guo Y, Li Q, Gao S, Zhou X, He Y, Shang X, et al. Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression in brain and gonad of Dmrt5 of zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(2):569–75.

Guan G, Kobayashi T, Nagahama Y. Sexually dimorphic expression of two types of DM (Doublesex/Mab-3)-domain genes in a teleost fish, the Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272(3):662–6.

Yang Y, Bayrer James R, Weiss MA. Doublesex and the regulation of sexual dimorphism in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(11):7280–92.

Matson CK, Zarkower D. Sex and the singular DM domain: insights into sexual regulation, evolution and plasticity. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(3):163–74.

Wexler JR, Plachetzki DC, Kopp A. Pan-metazoan phylogeny of the DMRT gene family: a framework for functional studies. Dev Genes Evol. 2014;224(3):175–81.

Miller SW, Hayward David C, Bunch Thomas A, Miller David J, Ball Eldon E, Bardwell Vivian J, et al. A DM domain protein from a coral Acropora millepora, homologous to proteins important for sex determination. Evol Dev. 2003;5(3):251–8.

Bellefroid EJ, Leclere L, Saulnier A, Keruzore M, Sirakov M, Vervoort M, et al. Expanding roles for the evolutionarily conserved Dmrt sex transcriptional regulators during embryogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(20):3829–45. doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1288-2.

Hand C, Uhlinger K. The culture, sexual and asexual reproduction, and growth of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Biol Bull. 1992;182:169–76.

Eckelbarger KJ, Hand C, Uhlinger K. Ultrastructural features of the trophonema and oogenesis in the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis (Edwardsiidae). Invertebr Biol. 2008;127(4):381–95.

Frank P, Bleakney JS. Histology and sexual reproduction of the anemone Nematostella vectensis Stephenson 1935. J Nat Hist. 1976;10(441–449):441–9.

Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W29–37.

Reitzel AM, Tarrant AM. Nuclear receptor complement of the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis: phylogenetic relationships and developmental expression patterns. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:230.

Tarrant AM, Reitzel AM, Blomquist CH, Haller F, Tokarz J, Adamski J. Steroid metabolism in cnidarians: insights from Nematostella vectensis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;301(1–2):27–36.

Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3406–15.

Wolenski FS, Layden MJ, Martindale MQ, Gilmore TD, Finnerty JR. Characterizing the spatiotemporal expression of RNAs and proteins in the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(5):900–15.

Genikhovich G, Technau U. In situ hybridization of starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) embryos, larvae, and polyps. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2009;2009(9):pdb prot5282.

Fraune J, Alsheimer M, Volff JN, Busch K, Fraune S, Bosch TC, et al. Hydra meiosis reveals unexpected conservation of structural synaptonemal complex proteins across metazoans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(41):16588–93.

Ebchuqin E, Yokota N, Yamada L, Yasuoka Y, Akasaka M, Arakawa M, et al. Evidence for participation of GCS1 in fertilization of the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis: implication of a common mechanism of sperm-egg fusion in plants and animals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;451(4):522–8.

Acknowledgements

NTK was supported by the NSF Ocean Sciences Postdoctoral Fellowship, Award Number OCE-1323652, and Award Number 1012629 from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Enrichment Program. AMR was supported by Award Number F32HD062178 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) during a postdoctoral fellowship in Dr. Ann Tarrant’s laboratory (WHOI) and Award Number R15GM114740 from National Institute of General Medicine (NIGMS). VS and EGK were supported by Binational Science Foundation Grant 2013119. AMR acknowledges generous funding from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NTK and AMR designed the experiments and analysis. EGK, VS, and AMR performed the experiments. NTK performed the protein and gene model analysis. JRF, EGK, and VS contributed to the analysis of the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Gene models from the Joint Genome Institute for all N. vectensis DMRTs. Red indicates the coding sequences, gray indicates buffer sequence, black indicates intron regions, and blue indicates UTR regions.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Primer sequences and the N. vectensis sequence ID used for cloning and quantitative PCR.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Traylor-Knowles, N.G., Kane, E.G., Sombatsaphay, V. et al. Sex-specific and developmental expression of Dmrt genes in the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis . EvoDevo 6, 13 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-015-0013-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-015-0013-7