Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects children and adults. Poor treatment adherence in AD requires interventions to promote self-management; patient education in chronic diseases is key to self-management. Many international AD management guidelines published to date include a recommendation for educating patients as part of their treatment but there are no formal recommendations on how to deliver this knowledge.

Main

We performed a scoping review to map the existing literature on patient education practices in AD and to highlight the clinical need for improved patient education in AD. The literature search was performed with the online databases MEDLINE, Embase, Grey Matters, ClinicalTrails.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). The search strategy yielded 388 articles. Of the 388 articles screened, 16 studies met the eligibility criteria, and the quantitative data was summarized by narrative synthesis. The majority of studies were randomized controlled trials conducted in Europe, Asia and North America. Since 2002, there have been limited studies evaluating patient education in the treatment of AD. Frequent education methods used included group-based educational programs, educational pamphlets, individual consultations and online resources. Education was most commonly directed at caregivers and their children. Only one study compared the efficacy of different education methods. In all included studies, the heterogenous nature of outcome measures and study design limited the consistency of results. Despite the heterogeneity of studies, patient education was shown to improve quality of life (QoL), disease severity and psychological outcomes in AD patients.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights that patient education is effective in a variety of domains relevant to AD treatment. Further comparative studies and randomized trials with longer-term follow-up are needed to provide validated and consistent patient education recommendations for AD; these may depend on age and population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atopic Dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema, is a chronic, relapsing-remitting, inflammatory skin disease that affects up to 20% of children [1]. AD has profound impacts on patient and caregiver quality of life (QoL). Pediatric and adult patients with AD experience pruritus, sleep impairment, social stigma, and negative mental health impacts [2, 3]. Since AD commonly affects children, the family impact of AD can be extensive, with parents reporting high stress and feelings of helplessness [4]. Cost of treatment adds to the burden of AD. Even if prescription treatments are covered, families are encouraged to make lifestyle changes such as purchase of specific clothing, emollients, soaps, detergents, and other items [5]. Direct financial costs of AD in the US are estimated to be $3.8 billion USD annually [6]. Direct costs, along with indirect costs such as time off due to doctor’s appointments, underline the need to optimize AD management.

There is no cure for AD, but it can be effectively controlled. Treatment adherence is poor; a study utilizing electronic monitoring found only 32% of patients followed their topical therapy in AD [7]. Factors contributing to poor outcomes include the complexity of treatment regimens, lack of knowledge, and corticosteroid phobia [8]. Nearly half of patients and caregivers cannot correctly identify the potency of commonly prescribed topical corticosteroids [9]. Incorrect application of topical therapy and poor adherence may result in poor clinical outcomes. Without proper management, psychosocial and financial difficulties are intensified, lowering the QoL for AD patients and families. If poor outcomes from inadequate adherence to treatment are misinterpreted as ineffectiveness of treatment, therapy may be inappropriately escalated.

Patient education is a key strategy to develop patient knowledge and foster skills required to help manage AD [10]. Patient education has been shown to improve QoL and treatment adherence in many chronic illnesses, including diabetes, asthma and cardiovascular disease [11]. Patient education has been established as one of four evidence-based cornerstones of asthma care [12] and the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support includes a validated, Diabetes Self-Management Education/Support education program that is widely used in clinical practice [13]. Patient education in the field of dermatology and specifically AD is less robustly developed. ‘Atopic schools’ established in some centres have proven effective in improving the management of AD but these programs differ in content, schedule, organization and evaluation [14]. Additionally, these ‘atopic schools’ are not feasible for healthcare centres with limited resources. The European, American, Japanese and Canadian guidelines for the management of AD recommend patient education programs as an adjunct to conventional therapy in AD [15,16,17,18]. Despite these recommendations there has been no evaluation of formalized and harmonized educational interventions.

Scoping reviews are conducted on a broad topic to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity in a heterogenous topic to determine knowledge gaps and future directions [19]., [20] This review was performed to provide a comprehensive, clinically useful summary of patient education in AD. The research questions this review aimed to address were:

-

1.

What is known from the literature about patient education in AD and has it improved management of the disease?

-

2.

What can be done to improve patient education for AD patients?

Methods

The protocol was drafted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-ScR) [21].

Inclusion criteria: Publications were included if they were written in English and involved a method of patient education in AD. Studies with various outcome measures including clinical, psychological and quality of life measurements were included to consider different aspects of AD management. Pediatric and adult populations were incorporated. For the pediatric population, education aimed at parents and caregivers was also included. In order to investigate how well participants retained information from education and how it impacted their outlook on the disease, we included studies that had one outcome directly measured by patient responses including interviews, surveys or questionnaires. This means that education studies which solely included validated scoring methods in disease severity and QoL (most commonly the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)) were excluded. Quality of life and disease severity are unique to an individual and are multi-factorial. For the purposes of our review we felt the best way to understand patients experiences with AD educational tools was to extrapolate our findings from direct patient reports instead of indirect index scores.

Exclusion criteria: Publications were excluded if they focused on education in occupational or contact dermatoses or other skin diseases that are not AD. Opinion pieces and conference abstracts/posters were excluded.

Databases and search strategy

Embase and MEDLINE were searched with no lower restriction on publication date until October 26, 2021. The results were exported to Covidence, a systematic review software. The search strategy was developed with an experienced librarian and refined through team discussion to include a search of Grey Matters and clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Search strategy: ((atopic dermatitis.mp. or eczema.mp.)AND(patient education.mp. or therapeutic education.mp. or health education.mp. or consumer health information.mp. or action plan.mp.)AND(questionnaire.mp. or exp questionnaire/ or survey.mp. or patient interview.mp.)).

Selection of articles

Two reviewers independently screened all abstracts from Embase and MEDLINE (B.W. and Y.A.), and searched Grey Matters, ClinicalTrials.gov and the ICTRP followed by full-text articles (where available) (B.W. and M.Z.). Disagreements were settled by a third-party reviewer if necessary (Y.A.).

Data charting

The data-charting was developed by B.W. and 16 eligible studies were charted and analyzed. Type of education method, study design, number and age of study participants, outcome measures for each study and if the outcome measures significantly improved were charted (Table 1). Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence included sample size, population, intervention and time at which outcome was measured.

Results

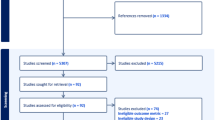

Of 388 results, 122 duplicates were removed and 266 were screened for title and abstract. Of these, 80 full-text publications were screened and 15 were included for data extraction. One additional study was identified by B.W. and M.Z. in the grey literature (Fig. 1). Active clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP were also searched on the topic and 4 were identified.

Summary of selected studies

Sixteen studies examined associations between patient education and management of AD [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The majority were from the United States (n = 4), Korea (n = 2) and Germany (n = 3). There was one study each from the following countries: Belgium, England, Spain, China, Brazil, Singapore and Japan. Data from 4,541 participants was represented. The largest study included 1,628 participants [33], while the smallest evaluated 18 patients [35]. The largest study had the shortest follow-up time of 2 weeks [33]. Time to follow-up was broad, ranging from 2 weeks to 1 year. One study measured outcomes at three time points after education [23], 6 studies measured outcomes at two time points [25, 26, 29, 30, 32, 34] and 8 studies measured outcomes at one time point [22, 24, 27, 28, 31, 33, 35,36,37]. Of the included studies, the majority directed education towards in caregivers and children (n = 12) [24,25,26, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Three studies reported on adults [22, 23, 27] and one study included all ages [30]. Most studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT; n = 11) [22,23,24, 26,27,28,29,30, 32, 35, 37] to examine the association between patient education and AD management. All studies evaluated multiple outcome measures; QoL (n = 9) [23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 31, 34, 36, 37] and disease severity (n = 10) [22, 23, 27,28,29, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37] were measured most frequently. Patient/caregiver knowledge or understanding (n = 5) [22, 25, 29, 34, 35], parental self-efficacy (n = 2) [34, 36] and depression/anxiety scores (n = 3) [27, 30, 32] were other outcome measurements.

Patient education in AD: Children & Caregivers

Twelve studies educated children with AD and their caregivers (Table 1) [24,25,26, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Most performed education in the presence of both child and caregiver while 3 studies targeted only parents/caregivers [25, 33, 37]. A variety of education methods were used including individual consultations with a healthcare professional [25, 26, 33], group based education sessions [29, 31, 32, 34, 37], eczema action plans [24, 35], a handbook [28] and the web-based education program that included self-assessment quizzes and written information about AD and its management (described in more detail below) [36].

Individual consultations

One study investigated the efficacy of pharmacist counseling on caregiver’s knowledge, level of confidence in care and satisfaction of counseling [25]. The counseling was efficacious in improving caregiver knowledge [25]. The other outcome measures were measured qualitatively but showed positive results [25]. Interestingly, this study reported only 34% of caregivers had received previous explanations on AD [25], suggesting that over half of the AD caregivers received a prescription before a treatment explanation.

Two studies implemented single nurse educational consultations of similar times (30–45 min). [26, 33]. The content of the consultations in both studies were similar, focusing mainly on reinforcing care recommendations, demonstrating practical skills and establishing parent’s/child’s knowledge and understanding of eczema. Although the interventions are comparable, the studies used different outcome measures. Chinn et al. measured changes in family impact and QoL at two time points (4 & 12 weeks) following the nurse consultation and found no significant improvement [26], whereas Rolinck-Werninghaus et al. measured parental assessments of their self-confidence in care and the child’s subjective disease severity and found both of these measures were improved 2 weeks after the consultation.

Group-based education

Group-based educational programs of varying lengths were used to educate AD children/caregivers in 5 studies [29, 31, 32, 34, 37]. Most were weekly sessions, occurring 4–6 times [29, 34, 37]. Group educational sessions were often interdisciplinary, led by nurse practitioners [29, 32], psychologists [37], pediatricians [37], dermatologists [29], elementary school teachers [34] and dieticians [37]. Two studies held group sessions with only caregivers present [32, 37]. The efficacy of these group programs was interpreted through measures of disease severity, QoL, knowledge, family impact, sleep disturbance, self-efficacy, treatment habits, treatment costs and coping strategies. Disease severity significantly improved after education in 60% (3/5) of the studies that measured this outcome [29, 31, 32], QoL improved in 50% (2/4 studies) [29, 31] and family impact improved in 33% (1/3 studies) [31]. Out of the other outcome measures, group education was shown to improve knowledge [29], self-efficacy [34], coping strategies [37] as well as treatment costs and habits [37]. Notably, one of these programs evaluated the effect of education on steroid phobia by measuring corticosteroid anxiety and corticosteroid use [32]. Significant improvements were seen in corticosteroid anxiety but there was no significant difference in the amount of corticosteroid used after education [32].

Eczema action plan

Two American studies used written eczema action plans (EAPs) as an education tool [24, 35]. EAPs usually include written treatment instructions for maintenance therapy and mild-severe flares which can be supplemented with cartoons/pictures for younger ages [38]. Brown et al. used a generic EAP [24] while the other study tailored EAPs to each patient given their age, location, and disease severity [35]. The latter study found that the EAP improved the patient’s/caregiver’s understanding of treatment but not their understanding of the disease itself [35]. Uniquely, Brown et al. also considered the effect an EAP may have on the medical providers of AD patients. Although after one month of use their EAP was ineffective in improving patient comfort, understanding or QoL, it was effective in improving provider comfort and understanding [24]. It is worth noting that both studies had small sample sizes, with less than 20 participants in each intervention group [24, 35]. Sample EAPs from these two studies can be found in our supplemental information section.

Online resource

Son & Lim developed a novel web-based education programme to overcome previous barriers in AD education [36]. The program was divided into two phases: Education I (Understanding of AD) and Education II (Management of AD), followed by a week of practice at home [36]. After each stage, online self-assessments were completed by participants. The results of these assessments showed that AD symptoms, QoL and self-efficacy were all improved 2 weeks after completion of the program [36].

Caregiver handbook

LeBovidge et al. designed a handbook that was given to caregivers as a take-home tool to help manage the child’s AD [28]. The handbook focused on understanding, treating and managing AD and discussed topic such as improving sleep, dealing with emotional challenges and teaching kids how to be part of skincare [28]. The study found improvement in caregiver confidence in the management of AD symptoms, but did not see improvement in AD symtoms, disease severity, QoL or family impact [28].

Patient education in AD: adults

Three studies educated adult patients with AD [22, 23, 27]. Similar to education in the AD pediatric population, outcome measures and education methods were diverse (Table 2).

Group-based education

In adults with AD, two studies facilitated extensive education through group sessions [23, 27]. Parallel to group education with children and caregivers, the adult group education programs emphasized interdisciplinary care, with instruction by dermatologists [23, 27], psychologists [23, 27], dieticians [23, 27], a dermatological nurse [23] and a sports, yoga and mindfulness coach [23]. Bostoen et al. studied the effectiveness of 2 h, twice weekly sessions concentrated on the patient’s skin disease, education on a healthy lifestyle and application of stress-reducing techniques [23]. After the program, disease severity, depression severity and QoL were assessed at 3, 6 & 9 months which revealed that there were no notable differences in scores between education participants and those who did not attend the group sessions [23]. In contrast, Heratizadeh et al. demonstrated that 12 h of a group training program significantly improved coping behavior with itching, QoL and disease severity [27].

Pamphlet vs. online video

The only comparative study in this review, Armstrong et al., investigated the effectiveness of an AD education pamphlet versus an online educational video for adults [22]. The video and pamphlet had information pertaining to clinical manifestations of AD, contributing environmental factors, bathing and hand-washing techniques, moisturizer vehicles, and common treatment modalities [22]. Despite both mechanisms of knowledge delivery containing identical information, the online video showed significantly greater decreases in disease severity and greater increases in AD knowledge [22].

Patient education in AD: all ages

One study looked at educating AD patients of all ages with the same tool [30]. Using an information booklet, investigators sought to determine how education impacts the emotional status of AD patients [30]. This study was the largest RCT in the review, with 564 participants in the intervention group and 683 controls. Emotional status was measured by levels of anxiety through the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The booklet containing information on important everyday patient-oriented aspects of AD only significantly improved STAI scores in ages 9-15yrs [30]. No other age groups showed benefits 3 or 6 months after receiving the booklet.

Discussion

We identified 16 interventional studies addressing patient education in AD across various settings and populations. We found that educating patients and caregivers in AD is currently a diverse practice, with limited cohesiveness on the methods used and the goals of education. Our findings indicate that patient education can improve several aspects of the complex disease, including QoL, clinical severity and key factors of self-management [22, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Despite these promising results, some studies showed mixed association between patient-education and AD improvements, while two studies showed no significant improvements in multiple domains [23, 26]. The first of these found no significant improvements in disease severity, depression severity or QoL between controls and an adult group-based education program for patients with mixed phenotypes of psoriasis and AD. Regarding immune mechanisms and treatment, psoriasis and AD are fundamentally different diseases [39, 40]. Assuming that the education program focused on overlapping aspects of both diseases, overlooking self-management knowledge and skills specific for AD could have limited its effectiveness in this disease population. Additionally, the study had a small sample size of 25 participants, with only 10 participants in the intervention group having AD [23]. This likely decreased statistical power to the point where significant differences were undetectable.

The second study employed a single nurse consultation for caregivers and their children aged 0.5-16yrs which was unsuccessful in improving family impact and QoL scores [26]. The investigators address several limitations that may have influenced outcomes including the type of medical practice, the characteristics of the patients and their parents, the numbers recruited, the follow-up period and the choice of outcome measures [26]. Unlike many other patient education studies which took place in secondary care settings, this study occurred in primary care with general practitioners. Participants were not selected based on disease severity subgroups and QoL scores on average, were lower than scores reported from secondary care populations [26, 41, 42], implying that the AD population in primary care may have milder disease activity. If baseline measures were low, it may have been more difficult to detect a meaningful change in this group.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this review is its incorporation of data from clinical trial registries and the grey literature, which is frequently excluded from traditional databases. Although selection bias is always possible, the inclusion of studies with negative results supports this search strategy. Restriction to studies published in English could lead to bias, although it is reassuring that the included articles come from a variety of countries.

One possible limitation of this scoping review is that it could be missing important papers due to the search criteria. As previously stated, studies were only included if they used patient-reported outcomes that are not related to disease severity. The main goals of patient education are to improve the patient’s knowledge and to empower them in order to facilitate self-management of the disease. Studies should try to quantify how effective the education tool was in achieving these goals using patient-reported outcomes such as knowledge scores, self-efficacy, self-confidence and psychological measures. Some AD patient education studies which only include QoL or disease severity scores [43,44,45,46] risk capturing the variability of external influences more so than the direct effects of education.

Future directions

Children and caregivers

Caregivers are important targets of education as the onset of AD occurs in 45% of children during the first 6 months of life, 60% during the first year of life and 85% before the age of 5 years [47]. Most studies targeted caregivers and their children. Few studies examined one education method for all ages. Targeting education to all ages of patients may not be ideal as learning styles and content may differ with phases of psychosocial development and disease trajectories [48]. There have been no studies to establish the time at which education should be directed toward children rather than parents. Considering parents spend 2 to 3 h per day caring for a child with AD, [49] defining the ideal age to directly educate the patient is essential in enabling self-management early on. Educating children in AD may pose challenges such as poor literacy and learning difficulties [50, 51]. For these reasons, education programs should be individually tailored to patients’ educational backgrounds. Alternatively, patient education guidelines suggest material should be written at sixth-grade or lower reading level, preferably including pictures and illustrations [52].

Adults

Although AD is commonly viewed as a pediatric disease, studies suggest adult AD is more frequent than previously recognized [53, 54]. Only three studies directed education at adults [22, 23, 27], suggesting education for adults with AD is extremely underdeveloped. AD can have a large impact on QoL in adults as occupational and psychosexual difficulties are well described [55] and a subset of adults have severe AD that is challenging to manage [56]. Education in the form of a training manual significantly improved coping behaviour, QoL and disease severity in adults with AD [27]. This supports the idea that patient education could help overcome challenges unique to adult AD and thus, requires more attention. However, being mindful that many adults with disease persistent from childhood experience heightened frustration and distrust stemming from prolonged exposure to the healthcare system [57], this attention and the aims of education should be distinct from the pediatric population.

Optimal delivery method

The available literature consists of a variety of study designs and education evaluations which makes direct comparison between studies impossible. Future RCT are needed to identify specific modalities (e.g., health care provider consultations vs. self-directed education) that would be more effective than others in achieving improved patient and caregiver confidence and competence in managing AD. The most effective methods are still being investigated to help develop standard education models. Current clinical trials in the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan are investigating pediatric AD education through methods of pharmacist led education, an educational video vs. handout and an allergy educator, respectively [58,59,60]. One Swiss clinical trial is evaluating the efficacy of a twice weekly educational session in adults [61].

When developing standard models, it is important to consider educating patients efficiently with available resources. A position paper from the International Eczema Council stated that education can improve QoL and patient satisfaction, but lack of funding and excessive bureaucracy limits its widespread implementation [62]. Many education interventions involved teaching by highly specialized and multidisciplinary professionals, [23, 29, 31, 34, 37] who are not widely accessible to AD patients nor feasible to hire in smaller health centers with limited resources. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the ageing “baby boomer” population has placed further pressure on providers caring for patients with AD [63, 64], highlighting the need for education methods that do not require the extensive training of professionals. It is worth devising and evaluating novel patient education tools that make the cost:benefit ratio of patient education more favourable.

Outcome measures

Evaluation of patient education is a complex but essential process, but is currently fragmented, as evidenced by the variable outcome measures across studies. To encompass the key features of patient education, assessment should include a biomedical outcome, QoL scores and specific psychological scores [10]. The ultimate goal of patient education is to provide patients knowledge to make autonomous decisions, [65] yet there are currently no known validated AD knowledge questionnaires. Efforts should be focused on developing patient-reported outcome tools capable of assessing acquired skills and knowledge. When evaluating education by surveys and questionnaires, patients and caregivers may interpret the nature of the questions differently depending on age, individual characteristics and backgrounds. For instance, DLQI scores have shown to be significantly higher for non-white patients compared to white patients with the same disease severity [66]. Evidence is needed to distinguish how variation in interpretation contributes to the observed differential effectiveness in patient education studies.

Follow-up

Considering the persistent, chronic nature of AD, appropriate follow-up in future studies is important to measure the efficacy of educational programs. The follow-up time in the educational studies included in this review ranged from two weeks to one year. Heratizadeh et al. 2017 demonstrated the long-term effectiveness of a training manual, as significant improvements in coping behaviour, QoL and disease severity were observed one year after the education intervention [27]. A group educational program for children also showed long term benefits, improving disease severity, QoL and knowledge after 3 and 6 months [29]. However, two weeks after educational intervention, no significant improvements were seen in disease severity in two studies [34, 36]. It has been suggested that educational interventions in AD should be followed up at least 1–3 months [67]. Prior to one month, disease severity may not be an accurate measurement as treated flare-ups can take several weeks to clear.

It may also be beneficial to perform follow-ups during different seasons. It is well known that AD flares are associated with seasonal changes, with increased temperatures predicting increased likelihood of AD office visits [68]. AD flares are commonly induced by viral illnesses [69] thereby, worsened disease severity in the winter may coincide with the increased prevalence of influenza and acute upper respiratory tract viral illnesses [70, 71]. Low temperatures in the winter can also cause AD by the drying of skin and spring season is associated with pollens, the main group of allergens that some patients feel worsen their AD symptoms [72]. If follow-ups are conducted in a different season than when the educational intervention took place, it could confound outcomes in disease severity.

Conclusion

This scoping review summarized the available data relating to the use of patient education in the treatment of AD to help guide future management. Compared to other chronic diseases, the lack of official recommendations for patient education in AD treatment is substantial. The significant improvements patient education facilitated in disease management support an increased effort to improve the quality of AD education provided in the clinical setting. Accurately measuring the effectiveness of patient education remains a challenge. The mixed associations in some studies highlights the need for higher quality, comparative research to identify optimal methods for AD education administration. Future studies with longer follow-up are needed to further prove patient education’s fundamental role in AD management.

Data Availability

All research analysed in this review is available through the online databases MEDLINE, Embase, Grey Matters, ClinicalTrials.gov or the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform repositories.

References

Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatology. 2011;131(1):67–73.

Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren M-M. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young american children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):607–11.

Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):428–33.

Balkrishnan R, Housman T, Carroll C, Feldman S, Fleischer A. Disease severity and associated family impact in childhood atopic dermatitis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(5):423–7.

Raimer SS. Managing pediatric atopic dermatitis. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39(1):1–14.

Mancini AJ, Kaulback K, Chamlin SL. The socioeconomic impact of atopic dermatitis in the United States: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(1):1–6.

Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, Camacho F, Kaur M, Carr D, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):211–6.

Sokolova A, Smith SD. Factors contributing to poor treatment outcomes in childhood atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56(4):252–7.

Beattie P, Lewis-Jones M. Parental knowledge of topical therapies in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis. Clin Experimental Dermatology: Viewpoints Dermatology. 2003;28(5):549–53.

Barbarot S, Bernier C, Deleuran M, De Raeve L, Eichenfield L, El Hachem M, et al. Therapeutic patient education in children with atopic dermatitis: position paper on objectives and recommendations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(2):199–206.

Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, Knight K, Hasselblad V, Gano A Jr, et al. Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illnesswhich ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):925.

Education NA, Program P. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):94–S138.

Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, Bollinger ST, Butcher MK, Condon JE, et al. 2017 National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(10):1409–19.

Stalder JF, Bernier C, Ball A, De Raeve L, Gieler U, Deleuran M, et al. Therapeutic patient education in atopic dermatitis: worldwide experiences. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(3):329–34.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink‐Wagner A, et al. Consensus‐based european guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78.

Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Sect. 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1218–33.

Katoh N, Ohya Y, Ikeda M, Ebihara T, Katayama I, Saeki H, et al. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2020. Allergology Int. 2020;69(3):356–69.

Lynde C, Barber K, Claveau J, Gratton D, Ho V, Krafchik B, et al. Canadian practical guide for the treatment and management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;8(Suppl 5):1–9.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synthesis Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, editors. Studying the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services: Research Methods. London: Routledge; 2001.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Armstrong AW, Kim RH, Idriss NZ, Larsen LN, Lio PA. Online video improves clinical outcomes in adults with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(3):502–7.

Bostoen J, Bracke S, De Keyser S, Lambert J. An educational programme for patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):1025–31.

Brown J, Weitz NW, Liang A, Friedman S, Stockwell MS. Does an Eczema Action Plan improve atopic dermatitis? A single-site Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Pediatr. 2018;57(14):1624–9.

Cheong JYV, Hie SL, Koh EW, de Souza NNA, Koh MJ-A. Impact of pharmacists’ counseling on caregiver’s knowledge in the management of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):105–9.

Chinn DJ, Poyner T, Sibley G. Randomized controlled trial of a single dermatology nurse consultation in primary care on the quality of life of children with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(3):432–9.

Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wasmann-Otto A, Niebuhr M, Wichmann K, Wollenberg A, et al. Effects of structured patient education in adults with atopic dermatitis: Multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):845.

Lebovidge JS, Timmons K, Delano S, Greco KF, Defreitas F, Chan F, et al. Improving patient education for atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial of a caregiver handbook. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(2):396–404.

Liang Y, Tian J, Shen CP, Ma L, Xu F, Wang H, et al. Therapeutic patient education in children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in China. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(1):70–5.

Lleonart M, Balana M, Guerra-Tapia A. Observational study to evaluate the impact of an educational/informative intervention in the emotional status (anxiety) of patients with atopic dermatitis (CUIDA-DEL). Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas. 2007;98(4):250–8.

Muzzolon M, Imoto RR, Canato M, Abagge KT, de Carvalho VO. Educational intervention and atopic dermatitis: impact on quality of life and treatment. Asia Pac Allergy. 2021;11(2):e21.

Ohya Y, Ito K, Futamura M, Masuko I, Hayashi K. Effects of a short-term parental education program on childhood atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(4):438–43.

Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Trentmann M, Lehmann C, Staab D, Reich A. Improved management of childhood atopic dermatitis after individually tailored nurse consultations: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(8):805–10.

Ryu H, Lee Y. The Effects of a School-Based Atopy Care Program for School-Aged children. West J Nurs Res. 2015;37(8):1014–32.

Shi VY, Lio PA, Nanda S, Lee K, Armstrong AW. Improving patient education with an eczema action plan: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149(4):481–3.

Son HK, Lim J. The effect of a web-based education programme (WBEP) on disease severity, quality of life and mothers’ self‐efficacy in children with atopic dermatitis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(10):2326–38.

Staab D, Von Rueden U, Kehrt R, Erhart M, Wenninger K, Kamtsiuris P, et al. Evaluation of a parental training program for the management of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(2):84–90.

Levy ML. Developing an eczema action plan. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):659–61.

Kaplan M. Current concepts in inflammatory skin Diseases evolved by Transcriptome Analysis: In-Depth analysis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):699.

Guttman-Yassky E, Krueger JG, Lebwohl MG. Systemic immune mechanisms in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with implications for treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(4):409–17.

Lawson V, Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Reid P, Owens RG. The family impact of childhood atopic dermatitis: the Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):107–13.

Lewis-Jones M, Finlay A, Dykes P. The infants’ dermatitis quality of life index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(1):104–10.

Moore EJ, Williams A, Manias E, Varigos G, Donath S. Eczema workshops reduce severity of childhood atopic eczema. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50(2):100–6.

Shaw M, Morrell DS, Goldsmith LA. A study of targeted enhanced patient care for pediatric atopic dermatitis (STEP PAD). Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(1):19–24.

Singer HM, Levin LE, Morel KD, Garzon MC, Stockwell MS, Lauren CT. Texting atopic dermatitis patients to optimize learning and eczema area and severity index scores: a pilot randomized control trial. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(4):453–7.

Staab D, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Kupfer J, Lob-Corzilius T, Ring J, et al. Age related, structured educational programmes for the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7547):933–8.

Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Boguniewicz M, Eigenmann P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):152–69.

Stenberg U, Haaland-Øverby M, Koricho AT, Trollvik A, Kristoffersen LGR, Dybvig S, et al. How can we support children, adolescents and young adults in managing chronic health challenges? A scoping review on the effects of patient education interventions. Health Expect. 2019;22(5):849–62.

Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, Nolan TM. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(2):159–62.

Strom M, Fishbein A, Paller A, Silverberg J. Association between atopic dermatitis and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in US children and adults. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(5):920–9.

Horev A, Freud T, Manor I, Cohen A, Zvulunov A. Risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25(3):210.

Safeer RS, Keenan J. Health literacy: the gap between physicians and patients. Am Family Phys. 2005;72(3):463–8.

Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(4):681–7. e11.

Margolis JS, Abuabara K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatology. 2014;150(6):593–600.

Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS, Taïeb A, Allen R, Hernanz-Hermosa JM, et al. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):226–32.

Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in adults. Med Clin. 2020;104(1):157–76.

Grant L, Seiding Larsen L, Trennery C, Silverberg JI, Abramovits W, Simpson EL, et al. Conceptual model to illustrate the symptom experience and humanistic burden associated with atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2019;30(4):247–54.

A pharmacist-led. parent/carer education program to support the management of atopic eczema in children. [Internet]. ISRCTN identifier: ISRCTN17846245. Updated Febr 21, 2022 [cited July 12, 2022].

Clinic-based Atopic Dermatitis Therapeutic Patient Education (AD-TPE). [Internet]. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04352270. Updated June 30, 2022 [cited July 12, 2022. ].

The Effect of Patient Education in. Initial Treatment of Children with Atopic Dermatitis by Pediatric Allergy Educator. [Internet]. JPRN identifier: JPRN-UMIN000012867. [cited Accessed July 12, 2022].

Haut-Tief Patient Education on Psoriasis. and Eczema [Internet]. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02205593. [cited July 12, 2022].

Barbarot S, Stalder J. Therapeutic patient education in atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(s1):44–8.

Wollina U. Challenges of COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(5):e13430.

Krämer U, Schikowski T. Recent demographic changes and consequences for dermatology. Skin Aging. 2006:1–8.

Wingard R. Patient education and the nursing process: meeting the patient’s needs. Nephrol Nurs J. 2005;32(2):211–4. quiz 5.

Nagpal N, Gordon-Elliott J, Lipner S. Comparison of quality of life and illness perception among patients with acne, eczema, and psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25(5).

Lee Y, Oh J. Educational programs for the management of childhood atopic dermatitis: an integrative review. Asian Nurs Res. 2015;9(3):185–93.

Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(4):465–71.

Ashbaugh AG, Kwatra SG. Atopic dermatitis disease complications. Manage Atopic Dermatitis: Methods Challenges. 2017:47–55.

Eccles R. An explanation for the seasonality of acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(2):183–91.

Monto AS. The seasonality of rhinovirus infections and its implications for clinical recognition. Clin Ther. 2002;24(12):1987–97.

Hadi HA, Tarmizi AI, Khalid KA, Gajdács M, Aslam A, Jamshed S. The epidemiology and global burden of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Life. 2021;11(9):936.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Health Sciences Librarian Sandra McKeown for her help in developing the search strategy.

Funding

N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BW created and performed the search strategy, screened all papers (abstract and full text) and was responsible for the writing of the manuscript.

MZ screened all papers (abstract and full text).

YA assisted in the search strategy, acted as a third party to resolve screening conflicts and was a major contributor in editing the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

YA reports honoraria and speaker fees from Pfizer, Novartis, Miravo, Sun Pharma, Leo, AbbVie, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Kirin, L’Oreal; research and education grants from Sanofi Canada, AbbVie, Pfizer, Novartis, Canadian Dermatology Foundation, Eczema Society of Canada; and performs clinical trials for Novartis and Leo.

BW and MZ report no competing interests.

This review was presented as a poster at the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This review was presented as a poster at the 2022 CSACI annual scientific meeting in Quebec City, QC.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilken, B., Zaman, M. & Asai, Y. Patient education in atopic dermatitis: a scoping review. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 19, 89 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-023-00844-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-023-00844-w