Abstract

Introduction

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A) is a novel tool that allows the detection of retinal vascular changes. We investigated the association of macular vessel density (VD) in the superficial plexus assessed by OCT-A with measures of cerebrovascular pathology and atrophy quantified by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in non-demented individuals.

Methods

Clinical, demographical, OCT-A, and brain MRI data from non-demented research participants were included. We analyzed the association of regional macular VD with brain vascular burden using the Fazekas scale assessed in a logistic regression analysis, and the volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) assessed in a multiple linear regression analysis. We also explored the associations of macular VD with hippocampal volume, ventricle volume and Alzheimer disease cortical signature (ADCS) thickness assessed in multiple linear regression analyses. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, syndromic diagnosis and cardiovascular variables.

Results

The study cohort comprised 188 participants: 89 with subjective cognitive decline and 99 with mild cognitive impairment. No significant association of regional macular VD with the Fazekas categories (all, p > 0.111) and WMH volume (all, p > 0.051) were detected. VD in the nasal quadrant was associated to hippocampal volume (p = 0.007), but no other associations of macular VD with brain atrophy measures were detected (all, p > 0.05).

Discussion

Retinal vascular measures were not a proxy of cerebrovascular damage in non-demented individuals, while VD in the nasal quadrant was associated with hippocampal atrophy independently of the amyloid status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebrovascular (CV) damage is a very common concomitant pathology to Alzheimer disease (AD) in the elderly, as shown in autopsy studies [1, 2] and is also involved in the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment [3]. In fact, the most frequent underlying cause of dementia in the elderly is mixed pathology (co-existence of AD and CV damage) [4]. Also, well-established cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and obesity are associated with an increased risk of developing AD [5].

The brain shares with the retina several developmental, functional, and pathophysiological features. Both are connected through bundles of neuronal axons forming the optic nerve and also blood vessels [6]. Related to the latter, the inner blood-retinal barrier is an analog of the blood–brain barrier [7]. Retinal capillary density differs regionally, in parallel to that in the brain, being greatest in the macula, while the periphery of the retina is almost avascular [8]. The retinal capillary network is organized in two distinct beds: the superficial plexus at the level of the ganglion cell layer, and the deep plexus at the outer plexiform layer [9].

The retinal microvasculature can be directly assessed in vivo using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography (OCT-A), while this is not possible for brain vessels through brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), thus the retina is considered to be “a window into the brain”. CV pathology usually remains undetected until significant damage has occurred and causes symptoms that warrant performance of brain imaging, while retinal vasculopathy may be identified non-invasively by OCT-A imaging early in the disease process. OCT-A obtains high-resolution images of the retina based on backscattered light from its neurosensory and vascular tissues, and it allows the visualization of retinal vascular abnormalities such as microaneurysms, neovascularization, vascular non-perfusion, reduced vascular density (VD), and enlarged foveal avascular zone (FAZ) [10]. OCT-A obtained the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2016 and in these past few years it has been used to evaluate a spectrum of ocular vascular diseases including diabetic retinopathy, retinal venous occlusion, uveitis, retinal arterial occlusion, and age-related macular degeneration, among others [10]. Growing evidence indicates that microvascular retinal changes could be markers of CV, neurodegenerative, and psychiatric diseases as well. In particular, in the field of cognitive impairment, changes in retinal vascular network geometry have been correlated with worse cognitive functioning [11], and several retinopathy signs have been associated with vascular and AD dementia [11, 12]. Also, several OCT-A quantitative retinal measures, such as VD and the size of the FAZ, have been investigated, pointing to a retinal vascular loss in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia patients compared to healthy controls [13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Thus, OCT-A is an emerging area of research in the field of novel biomarkers for cognitive decline and offers an exceptional opportunity to assess non-invasively both the retinal and also the brain microvasculatures.

In the present study, we explored OCT-A and brain MRI data from 188 non-demented participants from the Neuro-ophthalmology Research at Fundació ACE (NORFACE) cohort. Our main goal was to assess whether there was an association between retinal vascular damage (quantified as macular VD in the superficial plexus by OCT-A) and brain vascular damage (quantified as the Fazekas scale and the volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) by brain MRI). Additionally, we aimed to assess (1) the association between macular VD and several brain atrophy measures and (2) the influence of the amyloid status (+ / −) measured by positron emission tomography (PET) in the association of retinal vascular damage with brain vascular and atrophy measures. Our hypothesis was that retinal vascular measures are a proxy of CV damage and thus OCT-A could be used a surrogate marker of CV pathology, regardless of the presence of brain amyloidosis.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The Neuro-Ophthalmology Research at Fundació ACE (NORFACE) cohort was founded in 2014 to investigate retinal biomarkers of AD and examine the relationship between retinal changes and different types of neurodegenerative disorders [20]. In the present study, we included non-demented participants from the FACEHBI [21] and BIOFACE [22] research cohorts at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona with a diagnosis of either Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) [23] or MCI [24]. FACEHBI is a longitudinal observational study with the goal of investigating the pathophysiology of preclinical AD and the role of SCD as a risk marker for the future development of cognitive impairment [21]. For the present study, data from FACEHBI 5th follow-up visit (v5) were analyzed. BIOFACE is a longitudinal observational study focused on the analysis of novel biomarkers (including plasma-derived exosomes) in early-onset MCI patients [22]. For the present study, data from BIOFACE baseline visit (v0) were analyzed.

The cognitive status of all participants was assessed using the Neuropsychological Battery of Fundació ACE (NBACE) [25, 26]. NBACE is a brief, comprehensive and easy to administer test battery to detect cognitive impairment in the adulthood that covers the following cognitive domains: processing speed, orientation, attention, verbal learning and memory, language, visuo-perception, praxis, and executive functions. Participants classified as SCD presented cognitive complaints, a completely normal performance in all subtest of NBACE according to age and years of education, and preserved autonomy in daily life activities. Participants classified as MCI presented cognitive complaints, abnormal performance (low scores according to published cutoffs) in one or more NBACE subtests and preserved autonomy in daily life activities (no dementia).

For all participants, the following data were collected: demographics (age, sex, education), presence of cardiovascular risk factors (heart disease, respiratory disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and stroke), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [27] scores, syndromic diagnosis (SCD or MCI), amyloid status (positivity defined as Florbetaben (FBB) Centiloid > 13.5 [28] for FACEHBI participants and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio < 0.063 [29] for BIOFACE participants), apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 status, OCT-A (macular VD in the superficial plexus in four quadrants), and brain MRI (CV and atrophy measures).

Neuro-ophthalmological evaluation

Study participants underwent a complete neuro-ophthalmological evaluation that was performed by an optometrist and lasted about 20 min. The evaluation comprised: (1) review of past ophthalmological diseases, treatments, and surgeries, (2) monocular visual acuity assessment with the participants wearing their habitual correction for refractive error using a pinhole occluder and the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart [30, 31], (3) intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement by Icare tonometry [32], and (4) swept source (SS) OCT scan. More details can be found elsewhere [33].

Optical coherence tomography angiography

Participants were imaged with a DRI OCT Triton—SS OCT (Topcon Co. Tokyo, Japan). The OCT exam was completed in about 5–10 min, no pupil dilation was required and both eyes were scanned separately. Data were analyzed with the OCT Angiography Ratio Analysis (OCTARA) processing software. An automatic segmentation method was employed to obtain measures of the superficial vascular plexus, and the quantification of VD, expressed as the % of area covered by vessels. VD measures were obtained in a 6 × 6 mm area centered in the fovea. The central area (1 mm circle) was excluded from the analysis. The parafoveal area, defined by two concentric rings measuring 1- and 3-mm diameter, respectively, was subdivided into four quadrants: nasal, superior, temporal, and inferior. More details can be found in a recent publication [34]. Only VD measures from the right eye were used for the analysis, as in previous papers from our group [20, 33, 35].

Brain magnetic resonance imaging acquisition and processing

All participants underwent a structural MRI within a 6-month window after the clinical assessment and OCT-A. Imaging data were analyzed using the Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona Pipeline for Neuroimaging Analysis.

For FACEHBI participants, MRIs were acquired on a 1.5-T Siemens Magneton Aera (Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-channel head coil from Clínica Corachan (Barcelona). Anatomical T1-weighted images were acquired using a rapid acquisition gradient-echo three-dimensional (3D) magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) 2.200 ms, echo time (TE) 2.66 ms, inversion time (TI) 900 ms, slip angle 8°, field of view (FOV) 250 mm, slice thickness 1 mm, and isotropic voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm. Subjects also received axial T2-weighted, 3D isotropic fast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and axial T2*-weighted sequences to detect significant vascular pathology or microbleeds.

For BIOFACE participants, MRIs were acquired in a Siemens MAGNETOM VIDA 3 T scanner (Erlangen, Germany) using 32-channel head coil from Clinica Corachan (Barcelona). T1-weigthed images, for the morphological and the volumetric studies, were acquired using a gradient-echo 3D MPRAGE sequence with the following parameters: TR 2.200 ms, TE 2.23 ms, TI 968 ms, 1.2-mm slice thickness, FOV 270 mm, and voxel measurement 1.1 × 1.1 × 1.2 mm. In order to complete the acquisition a 3D isotropic FLAIR, an axial sequence T2-weighted, and an axial sequence T2*-weighted will be performed to detect vascular brain damage and microbleeds.

1.5-T and 3-T MRI images from the two cohorts (FACEHBI and BIOFACE) were analyzed together, as the scanner resolution (1.5 T vs 3 T) only affects image resolution (accuracy of the measurement) not the measurement per se. Additionally, all images were converted to the 1-mm3 voxel resolution, so the differences in measurements were even less noticeable.

MRI images were stored in a picture archiving communication system (PACS) system and submitted to an automated process of de-identification.

Two parameters were used to assess cerebrovascular damage: the Fazekas scale [36] and the volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMH).

The Fazekas scale is a visual assessment scale that divides the white matter into periventricular and deep white matter [36]. Each region is given a grade depending on the size and confluence of the lesions: (a) periventricular white matter (PVWM) (0 = absent, 1 = caps or pencil-thin lining, 2 = smooth halo, 3 = irregular periventricular signal extending into the deep white matter) and (b) deep white matter (DWM) (0 = absent, 1 = punctate foci, 2 = beginning confluence, 3 = large confluent areas). Image quantification using the Fazekas scale was performed by two expert radiologists who were blind to demographic characteristics and diagnostic status of participants. For the present analysis, as the Fazekas scale a high positive asymmetric distribution, scores were dichotomized into two categories: absence (Fazekas 0–1) and presence (Fazekas 2–3) of significant CV pathology.

The volume of WMH was calculated as follows. First, T2-FLAIR was registered into T1w native space with Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) 3.0 software package [37]. Then with T1w and T2-FLAIR registered images, we used the U-Net with multi-scale highlighting foregrounds method described elsewhere [38] and the PGS software provided by the authors. The software isolates the WMH regions so the WMH volume could be straightforwardly obtained with FMRIB Software Library v6.0 tools [39] (Fig. 1). No partial volume correction was applied for the determination of WMH volume, since it should be equal to zero in a healthy brain regardless of the intracranial volume. Additionally, sex is the main contributor to the variation in intracranial volume and it was included as an adjusting factor in all the analysis.

Representative MRI T2-weighted images from a 68-year-old male with SCD showing A substantial WMH damage (Fazekas scale score = 3) and B isolation and masking of the WMH burden (in red) using the PGS software. Abbreviations: MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; WMH: white matter hyperintensitiy; SCD: subjective cognitive decline

Additionally, we calculated several structural brain parameters related to AD atrophy patterns: the hippocampal volume, the ventricle volume, and the Alzheimer’s disease cortical signature (ADCS) thickness. MRI T1w images underwent a Freesurfer 7.2 reconstruction [40,41,42]. Hippocampal volume was calculated as the sum of right and left hippocampus volume and adjusted by the estimated intracranial volume using the residual method [43]. Ventricle volume was calculated as the sum of the reconstructed ventricles and adjusted by the estimated intracranial volume using the residual method. Lastly, the ADCS was expressed by a meta-region of interest (ROI) composed of the following areas: entorhinal, inferior temporal, middle temporal, and fusiform. The average thickness of the ADCS ROI was calculated as the mean thickness across these regions weighted by their surface area [44,45,46].

Statistical analyses

Data processing and analysis were carried out using R 4.1.2 [47]. All quantitative data were checked for normality, skewness, and range restriction. A log transformation was applied to those measures that did not follow a normal distribution (WMH burden and ventricle volume). Demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, MMSE score, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, smoking, and stroke) were examined using frequency analysis (Student’s t and Pearson’s chi-square tests) to characterize their distribution between the two diagnostic groups (SCD vs MCI). In the following analyses, only those variables which prevalence was greater than 5% of the total cohort were included.

For the final models, we included cardiovascular variables (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking) as adjusting factors. In order to determine which demographic and clinical variables should be additionally included as adjusting factors in the models, four multiple linear regression analyses were carried out to study their distribution among the four regional macular VD measures, separately. We examined the following variables: age, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, amyloid (A) status, and syndromic diagnosis (SCD vs MCI), using cardiovascular variables (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking) as adjusting factors. For all the analyses, alpha level was set at 0.05.

Five linear regression analyses were performed to determine the capacity of each regional macular VD measure to discriminate brain vascular and structural changes. Those demographic and clinical variables that showed a significant impact in the previous multiple linear regression analyses, along with cardiovascular variables (heart disease, respiratory disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, and diabetes mellitus), were included as adjusting factors in the analyses. All the regression analyses described below were performed as follows: first, we ran the analyses without the adjusting factors, and then introduced those to assess their effect on the discrimination task.

First, a logistic regression analysis of the association of regional VD measures between the Fazekas categories was performed. We reported the odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval, the z-scores, and significance. Then, four different multiple linear regression analyses of the association of each regional macular VD measure with the WMH volume, hippocampal volume, ventricle volume, and the ADCS thickness as outcomes, separately, were performed. For these analyses, we reported regression coefficients, t-value, significance, and beta. Alpha level was set at 0.0125 after Bonferroni correction.

Lastly, the former analyses were repeated to assess the interaction between the A status and the four regional VD measures to discriminate brain vascular (Fazekas categories, WMH volume) and structural (hippocampal volume, ventricle volume and ADCS thickness) features, separately. Alpha level was set at 0.0125 after Bonferroni correction.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort

Data from 275 participants who completed v5 of the FACEHBI study and v0 of the BIOFACE study were initially reviewed (Fig. 2). Several exclusion criteria were applied: lack of OCT-A measures (n = 28), lack of brain MRI (n = 11), time between OCT-A and brain MRI > 6 months (n = 4), lack of Aβ positron emission tomography (PET) or CSF biomarkers (n = 21), lack of APOE genotype (n = 1), and finally, ophthalmological conditions that could interfere with the OCT-A measurements (n = 23: n = 4 due to retinal surgery, n = 1 due to retinopathy, n = 7 due to open-angle glaucoma, n = 3 due to IOP > 24 mmHg, n = 4 due to other reasons)).

The final sample consisted of 188 individuals (89 with SCD and 99 with MCI) who completed FACEHBI v5 or BIOFACE v0 and had OCT-A, brain MRI, amyloid status, and APOE genotype information available.

Demographic characteristics and past medical history of participants are displayed in Table 1. Compared to SCD individuals, those in the MCI group showed younger age (64.35 ± 6.82 vs 68.47 ± 7.27, p < 0.001), fewer years of education (12.41 ± 5.11 vs 15.71 ± 4.24, p < 0.001), lower MMSE scores (27.91 ± 1.64 vs 29.07 ± 1.15, p < 0.001), lower rates of respiratory disease (6.06% vs 16.85%, p = 0.035), and higher rates of smoking (49.49% vs 22.47%, p < 0.001).

Regarding biomarker data (see Table 2), MCI and SCD participants showed similar rates of amyloidosis (25.25% vs 31.46%, p = 0.434) and CV damage (Fazekas category 2–3: 7.07% vs 14.62%, p = 0.151; WMH volume (3020.31 ± 4289.90 vs 3408.14 ± 4752.04, p = 0.559)). MCI participants showed significantly higher regional macular VD measures compared to the SCD group in the nasal, temporal, and inferior quadrants (p = 0.029, p < 0.001, and p = 0.024, respectively).

Multiple linear regression analyses of clinical, demographic, and biomarker variables with regional VD measures

The multiple linear regression analysis exploring the association of age, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, A status, and syndromic diagnosis (SCD vs MCI) with each regional macular VD measure showed that age had a significant effect on macular VD in the nasal, temporal, and inferior quadrants (all, p < 0.027), sex had a significant effect on macular VD in the temporal quadrant (p = 0.033), and syndromic diagnosis had a significant effect on macular VD in the temporal and superior quadrants (p < 0.043), so those were included as adjusting factors in all following analyses (Additional file 1).

Logistic regression analysis of the association of macular VD and Fazekas categories

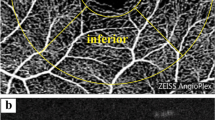

Representative images of OCT-A and brain MRIs from study participants are depicted in Fig. 3.

Representative OCT-A and brain MRI images from the study participants. A 68-year-old female with SCD and high CV damage (Fazekas scale score = 2, WMH volume = 30,943 mm3). B 61-year-old female with MCI and high CV damage (Fazekas scale score = 3, WMH volume = 27,000 mm3). C 61-year-old female with SCD and low CV damage (Fazekas scale score = 0, WMH volume = 290 mm3). D 60-year-old female with MCI and low CV damage (Fazekas scale score = 0, WMH volume = 710 mm3). Abbreviations: CV: cerebrovascular; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MRI: magnetic ressonance imaging; OCT-A: Optical Coherence Tomography – angiography; SCD: subjective cognitive decline; WMH: white matter hyperintensity

The association of regional macular VD measures with the Fazekas categories is depicted in Tables 3 and 4, with and without including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, and cardiovascular variables as adjusting factors.

Regression models revealed that regional macular VD measures were not able to discriminate the Fazekas categories (all p > 0.111, Fig. 4). Age (p = 0.006), hypertension (p = 0.003), and smoking (p = 0.005) showed a significant association with the Fazekas categories.

Adjusted macular VD measurements by Fazekas categories. Macular VD differences between Fazekas categories in A nasal, B superior, C temporal, and D inferior quadrants. Macular VD measures are adjusted by age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking. Abbreviations: n.s.: non-significant; VD: vessel density

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of macular VD with WMH volume

The association of regional macular VD measures with WMH volume, with and without including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, and all cardiovascular variables as adjusting factors, are shown in Tables 5 and 6. Regression models revealed that regional macular VD was not associated to WMH volume (all, p > 0.051, Fig. 5). Age showed a positive association with the WMH volume (p < 0.001).

Association of macular VD and WMH volume. Association of macular VD in A nasal, B superior, C temporal, and D inferior quadrants with WHM volume. Macular VD measures are adjusted by age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking. Abbreviations: n.s.: non-significant; VD: vessel density; WMH: white matter hyperintensity

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of macular VD with brain atrophy measures

The associations of regional macular VD with brain atrophy measures, with and without including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, and cardiovascular variables as adjusting factors, are depicted in Additional files 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. Regression models showed that VD in the nasal quadrant was significantly associated to hippocampal volume (p = 0.007, Fig. 6). On the other hand, VD measures were not associated to other measures of brain atrophy such as ventricle volume (all, p > 0.657, Fig. 7) or ADCS thickness (all, p > 0.235, Fig. 8). Age showed a negative association with hippocampal volume (p < 0.001, Additional file 2) and a positive association with ventricle volume (p < 0.001, Additional file 4). Diabetes showed a positive association with ventricle volume (p = 0.001, Additional file 4). Lastly, syndromic diagnosis showed a negative association with ADCS thickness (p < 0.001, Additional file 6).

Association of macular VD and hippocampal volume. Association of macular VD in A nasal, B superior, C temporal, and D inferior quadrants with hippocampal volume. Macular VD measures are adjusted by age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking. Abbreviations: n.s.: non-significant; VD: vessel density; WMH: white matter hyperintensity

Association of macular VD and ventricle volume. Association of macular VD in A nasal, B superior, C temporal, and D inferior quadrants with ventricle volume. Macular VD measures are adjusted by age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking. Abbreviations: n.s.: non-significant; VD: vessel density

Association of macular VD and ADCS thickness. Association of macular VD in A nasal, B superior, C temporal, and D inferior quadrants with ACDS thickness. Macular VD measures are adjusted by age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease, and smoking. Abbreviations: ADCS: Alzheimer’s disease cortical signature; non-significant; VD: vessel density

Interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating CV damage and brain atrophy

Regression models showed that the interaction of the A status with macular VD had no effect in differentiating Fazekas categories (all p > 0.079, Additional file 8), WMH volume (all p > 0.374, Additional file 9), hippocampal volume (all p > 0.328, Additional file 10), ventricle volume (all p > 0.410, Additional file 11), or ADCS thickness (all p > 0.065, Additional file 12). Thus, the association of macular VD with measures of CV damage and brain atrophy was not significantly influenced by the A status.

Discussion

We investigated the relationship of macular VD in the superficial plexus quantified by OCT-A with measures of CV pathology and brain atrophy in 188 non-demented participants from two research cohorts at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona. Our data suggested that macular VD was not a proxy of CV burden but was significantly associated with hippocampal atrophy independently of amyloid status.

In the dementia field, the early identification of CV pathology is crucial, as asymptomatic brain vascular changes in middle-aged adults are associated with a higher risk of future cognitive decline and disability [48]. Preliminary data suggested that OCT-A had the potential to be used as an alternative, direct, and non-invasive method to assess the health of brain vasculature in early stages of CV damage instead of conventional imaging techniques such as brain MRI, which has a limited diagnostic accuracy and does not allow the in vivo visualization of brain microvasculature. Two publications from large cohorts supported this idea, showing significant associations between vascular retinal changes and CV pathology. First, changes in retinal vascular calibers (narrower arterioles and wider venules) from fundus photographs showed an association with poor white matter microstructure on diffusor tension MRI [49]. Second, subclinical cerebral infarcts were associated with retinal microvascular abnormalities (arteriovenous nicking, focal arteriolar narrowing, blot hemorrhages, soft exudates, and microaneurysms) in individuals with hypertension [50]. Additionally, several smaller studies also highlighted a similar association between retinal and brain vascular pathology [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Our current results, though, do not support the correlation of retinal vs brain vascular changes, as we did not detect a significant association of macular VD with the Fazekas scale scores and WMH volume assessed by brain MRI. We believe that the discrepancy between our data and results from previous publications might be due to several factors. First of all, one of the main methodological differences among published data are the measures used to assess retinal and brain vascular damage, which differ widely among works (for retinal measures: retinal vascular calibers, arteriovenous nicking, arteriolar narrowing, arterial tortuosity, hemorrhages, exudates, microaneurysms, wall-to-lumen arterial ratio, skeleton density of capillaries, VD, arterial fractal dimension; for brain measures: diffusor tensor for WM microstructure assessment, presence of cerebral infarcts, volume of WMH, markers of vascular integrity, CV reactivity in WM …). In particular, in our study, we used a quantitative measure of retinal vascular pathology (macular VD in the superficial vascular plexus in four different quadrants) and both semi-quantitative and quantitative data to measure CV damage (the Fazekas scale and WMH volume by Freesurfer, respectively), which were not directly comparable with any other publications. Additionally, the type of population (with and without cognitive impairment, with or without CV risk factors, with or without stroke) and number of participants included also varied among studies and could be influencing the outcomes. The types of retinal devices (OCT vs fundus photography) and brain MRI used for the vascular quantifications could play a part in the discrepant results among publications. Lastly, the methods used in our publication might not be sensitive enough to detect very small effects in the association of retinal and brain vascular measures.

It is well known that CV damage and neurodegeneration develop in parallel, thus we aimed to additionally investigate the relationship of retinal vascular changes with measures of brain atrophy. Our study detected that retinal vascular loss in the nasal quadrant (lower VD) was significantly associated with hippocampal atrophy, while the other measures of brain atrophy investigated (ventricle volume and ADCS thickness) were not related to retinal vascular changes. Although multiple works have demonstrated a significant association between retinal structural changes (retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and macular thinning mostly) and brain atrophy [59,60,61,62,63,64], few publications have focused on the specific relationship of retinal vasculature with brain structural changes. Similar to our results, Hu et al. showed a positive association between retinal VD and gray matter volumes of the hippocampal subfields in 25 cognitively impaired patients (17 MCI and 8 AD dementia) [65].

Finally, our data showed that the association of macular VD with measures of CV damage and brain atrophy was not significantly influenced by the brain amyloid status of the participants, assessed by either CSF of PET. This particular issue had not been clearly addressed in previous publications correlating retinal and brain vascular damage, which either did not report the amyloid status of participants [48,49,50,51,52,53,54] or analyzed altogether data of participants with presence and absence of brain amyloidosis [57]. Our result also fits with a previous publication from our group using data from the NORFACE cohort, showing that macular VD did not significantly differ between Alzheimer and Normal AT(N) categories assessed by CSF biomarkers, and that macular VD was not correlated with CSF Aβ1-42 [66].

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. First of all, our cohort had a relatively low burden of CV pathology (only 10.64% of the sample belonged to the Fazekas 2–3 group). Second, our data was obtained from two research studies, not necessarily reflecting retinal and brain vascular changes of real-world patients with cognitive decline. Third, our results were cross-sectional, not being able to show changes over time in macular VD or brain MRI measures. Forth, the VD measures employed were limited to the macular region and the superficial vascular plexus, lacking information about FAZ and VD in the deep vascular plexus. Lastly, we lacked information about CV-related drugs taken by the study participants and the quality of the OCT-A images.

We also consider that our study has several strengths compared to previous works. Our cohort consisted of a relatively large and single-site sample of non-demented research participants who underwent similar testing and biomarkers. We limited our analysis to data from the right eye. Our participants’ age range was quite large (51–91), allowing us to potentially detecting macular VD changes in early and late ages. Notably, we used several cardiovascular risk factors as adjusting factors in all the analysis. Lastly, the neurologist and optometrist were blinded of each other’s diagnosis.

In summary, our study does not support that macular VD in the superficial plexus assessed by OCT-A is a proxy of CV damage in a research cohort of non-demented individuals with SCD and MCI.

Availability of data and materials

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- A:

-

Amyloid

- AD:

-

Alzheimer disease

- ADCS:

-

Alzheimer disease cortical signature

- ANT:

-

Advanced normalization tools

- APOE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CSVD:

-

Cerebral small-vessel disease

- CV:

-

Cerebrovascular

- DWM:

-

Deep white matter

- ETDRS:

-

Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study

- FACEHBI:

-

Fundació ACE Healthy Brain Initiative

- FAZ:

-

Foveal avascular zone

- FBB:

-

Florbetaben

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- IOP:

-

Intraocular pressure

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MPRAGE:

-

Magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NBACE:

-

Neuropsychological Battery of Fundació ACE

- NORFACE:

-

Neuro-ophthalmology Research at Fundació ACE

- OCT-A:

-

Optical coherence tomography angiography

- OCTARA:

-

OCT Angiography Ratio Analysis

- PACS:

-

Picture archiving communication system

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PVWM:

-

Periventricular white matter

- RNFL:

-

Retinal nerve fiber layer

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- SCD:

-

Subjective cognitive decline

- SS:

-

Swept source

- TE:

-

Echo time

- TI:

-

Inversion time

- TR:

-

Repetition time

- V0:

-

Baseline visit

- V5:

-

5th FACEHBI follow-up visit

- WMH:

-

White matter hyperintensities

References

Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke; 2011. p. 2672–713. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21778438/

Attems J, Jellinger KA. The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease--lessons from pathology. BMC Med. 2014;12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25385447/

Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, Nation DA, Schneider LS, Chui HC, et al. Vascular dysfunction-The disregarded partner of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:158–67. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30642436/.

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–204. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17568013/.

Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25030513/.

Shi H, Koronyo Y, Rentsendorj A, Fuchs DT, Sheyn J, Black KL, et al. Retinal Vasculopathy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:1211.

Gariano RF, Gardner TW. Retinal angiogenesis in development and disease. Nature. 2005;438:960–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16355161/.

DeBuc DC, Somfai GM, Koller A. Retinal microvascular network alterations: Potential biomarkers of cerebrovascular and neural diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H201–12. Available from: http://www.ajpheart.orgH201.

Toussaint D, Kuwabara T, Cogan DG. Retinal vascular patterns. II. Human retinal vessels studied in three dimensions. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;65:575–81. Available from: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archopht.1961.01840020577022.

Kashani AH, Chen CL, Gahm JK, Zheng F, Richter GM, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography: A comprehensive review of current methods and clinical applications. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;60:66–100. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28760677/.

Gatto NM, Varma R, Torres M, Wong TY, Johnson PL, Segal-Gidan F, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and cognitive function in Latino adults in Los Angeles. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:127–36. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22568425/.

Qiu C, Cotch MF, Sigurdsson S, Jonsson PV, Jonsdottir MK, Sveinbjörnsdottir S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds, retinopathy, and dementia: the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2221–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21172845/.

Baker ML, Larsen EKM, Kuller LH, Klein R, Klein BEK, Siscovick DS, et al. Retinal microvascular signs, cognitive function, and dementia in older persons: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2007;38:2041–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17525385/.

Wu J, Zhang X, Azhati G, Li T, Xu G, Liu F. Retinal microvascular attenuation in mental cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease by optical coherence tomography angiography. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:e781–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32153141/.

Jiang H, Wei Y, Shi Y, Wright CB, Sun X, Gregori G, et al. Altered macular microvasculature in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. J Neuro Ophthalmol. 2018;38:292–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29040211/.

Querques G, Borrelli E, Sacconi R, De Vitis L, Leocani L, Santangelo R, et al. Functional and morphological changes of the retinal vessels in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Sci Rep. 2019;9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30635610/

Biscetti L, Lupidi M, Luchetti E, Eusebi P, Gujar R, Vergaro A, et al. Novel non‐Invasive Biomarkers of Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease: the Role of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and OCT‐Angiography (OCT‐A). Eur J Neurol. 2021;ene.14871. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ene.14871

Zabel P, Kaluzny JJ, Wilkosc-Debczynska M, Gebska-Toloczko M, Suwala K, Zabel K, et al. Comparison of retinal microvasculature in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and primary open-angle glaucoma by optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:3447–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31408108/.

Zhang YS, Zhou N, Knoll BM, Samra S, Ward MR, Weintraub S, et al. Parafoveal vessel loss and correlation between peripapillary vessel density and cognitive performance in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s Disease on optical coherence tomography angiography. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0214685. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30939178.

Sánchez D, Castilla-Marti M, Rodríguez-Gómez O, Valero S, Piferrer A, Martínez G, et al. Usefulness of peripapillary nerve fiber layer thickness assessed by optical coherence tomography as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30397251/

Rodriguez-Gomez O, Sanabria A, Perez-Cordon A, Sanchez-Ruiz D, Abdelnour C, Valero S, et al. FACEHBI: A Prospective Study of Risk Factors, Biomarkers and Cognition in a Cohort of Individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline. Study Rationale and Research Protocols. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4:100–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29186280/.

Esteban-De Antonio E, Pérez-Cordón A, Gil S, Orellana A, Cano A, Alegret M, et al. BIOFACE: A Prospective Study of Risk Factors, Cognition, and Biomarkers in a Cohort of Individuals with Early-Onset Mild Cognitive Impairment. Study Rationale and Research Protocols. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;1–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34420953/

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10:844–52 . Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24798886/.

Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. J Intern Med; 2004. p. 183–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15324362/

Alegret M, Espinosa A, Vinyes-Junqué G, Valero S, Hernández I, Tárraga L, et al. Normative data of a brief neuropsychological battery for Spanish individuals older than 49. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:209–19.

Alegret M, Espinosa A, Valero S, Vinyes-Junqué G, Ruiz A, Hernández I, et al. Cut-off scores of a brief neuropsychological battery (NBACE) for Spanish individual adults older than 44 years old. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76436. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24146868.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1202204/.

Bullich S, Roé-Vellvé N, Marquié M, Landau SM, Barthel H, Villemagne VL, et al. Early detection of amyloid load using 18F-florbetaben PET. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33773598/

Orellana A, García-González P, Valero S, Montrreal L, de Rojas I, Hernández I, et al. Establishing In-House Cutoffs of CSF Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers for the AT(N) Stratification of the Alzheimer Center Barcelona Cohort. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6891. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35805894/.

Bokinni Y, Shah N, Maguire O, Laidlaw DAH. Performance of a computerised visual acuity measurement device in subjects with age-related macular degeneration: Comparison with gold standard ETDRS chart measurements. Eye (Basingstoke). 2015;29:1085–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26043703/.

Chew EY, Lindblad AS, Clemons T. Summary results and recommendations from the age-related eye disease study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1678–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20008727/.

Pakrou N, Gray T, Mills R, Landers J, Craig J. Clinical comparison of the Icare tonometer and Goldmann applanation tonometry. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:43–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18303384/.

Marquié M, Valero S, Castilla-Marti M, Martínez J, Rodríguez-Gómez O, Sanabria Á, et al. Association between retinal thickness and β-amyloid brain accumulation in individuals with subjective cognitive decline: Fundació ACE Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:37.

Marquié M, Valero S, Martínez J, Alarcón-Martín E, García-Sánchez A, de Rojas I, et al. Differences in macular vessel density in the superficial plexus across cognitive impairment: the NORFACE cohort. Sci Rep. 2022;12:16938. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36209290/.

Sánchez D, Castilla-Marti M, Marquié M, Valero S, Moreno-Grau S, Rodríguez-Gómez O, et al. Evaluation of macular thickness and volume tested by optical coherence tomography as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in a memory clinic. Sci Rep. 2020;10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32005868/

Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 15 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3496763/.

Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2033–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20851191/.

Park G, Hong J, Duffy BA, Lee JM, Kim H. White matter hyperintensities segmentation using the ensemble U-Net with multi-scale highlighting foregrounds. Neuroimage. 2021;237. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33957235/

Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21979382/.

Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9:195–207. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9931269/.

Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9931268/.

Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11050–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10984517/.

Mathalon DH, Sullivan EV, Rawles JM, Pfefferbaum A. Correction for head size in brain-imaging measurements. Psychiatry Res. 1993;50:121–39. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8378488/.

Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Knopman DS, Lowe V, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence of cerebral β-amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired individuals aged 50–95 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:435–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28456479/.

Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:205–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27697430/.

Milà-Alomà M, Brinkmalm A, Ashton NJ, Kvartsberg H, Shekari M, Operto G, et al. CSF Synaptic Biomarkers in the Preclinical Stage of Alzheimer Disease and Their Association With MRI and PET: a Cross-sectional Study. Neurology. 2021;97:E2065–78. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34556565/.

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 13 Feb 2023.

Lin CH, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Chen CH. Vascular aging and cognitive dysfunction: silent midlife crisis in the brain. Pulse. 2017;5:127–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29761088/.

Mutlu U, Cremers LGM, De Groot M, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, Van Der Lugt A, et al. Retinal microvasculature and white matter microstructure: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2016;87:1003–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27511186/.

Cooper LS, Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, Bryan RN, Hubbard LD, et al. Retinal Microvascular Abnormalities and MRI-Defined Subclinical Cerebral Infarction. Stroke. 2006;37:82–6. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/01.str.0000195134.04355.e5.

Abdelhak A, Huss A, Brück A, Sebert U, Mayer B, Müller HP, et al. Optical coherence tomography-based assessment of retinal vascular pathology in cerebral small vessel disease. Neurol Res Pract. 2020;2. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33324919/

Geerling CF, Terheyden JH, Langner SM, Kindler C, Keil VC, Turski CA, et al. Changes of the retinal and choroidal vasculature in cerebral small vessel disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35256658/

Korann V, Suhas S, Appaji A, Nagendra B, Padmanabha A, Jacob A, et al. Association between retinal vascular measures and brain white matter lesions in schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;70:103042.

Kwa VIH, Van der Sande JJ, Stam J, Tijmes N, Vrooland JL. Retinal arterial changes correlate with cerebral small-vessel disease. Neurology. 2002;59:1536–40. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/59/10/1536.

Wiseman SJ, Zhang JF, Gray C, Hamid C, Valdés Hernández M del C, Ballerini L, et al. Retinal capillary microvessel morphology changes are associated with vascular damage and dysfunction in cerebral small vessel disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2023;43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36300327/

van de Kreeke JA, Nguyen HT, Konijnenberg E, Tomassen J, den Braber A, ten Kate M, et al. Retinal and Cerebral Microvasculopathy: Relationships and Their Genetic Contributions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:5025–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30326071/.

Lee JY, Kim JP, Jang H, Kim J, Kang SH, Kim JS, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography as a potential screening tool for cerebral small vessel diseases. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32527301/.

Wang X, Wei Q, Wu X, Cao S, Chen C, Zhang J, et al. The vessel density of the superficial retinal capillary plexus as a new biomarker in cerebral small vessel disease: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:3615–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33432462/.

den Haan J, Janssen SF, van de Kreeke JA, Scheltens P, Verbraak FD, Bouwman FH. Retinal thickness correlates with parietal cortical atrophy in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and controls. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;10:49–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29201990/.

Méndez-Gómez JL, Pelletier A, Rougier MB, Korobelnik JF, Schweitzer C, Delyfer MN, et al. Association of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness with brain alterations in the visual and limbic networks in elderly adults without dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30646353/

Shi Z, Zheng H, Hu J, Jiang L, Cao X, Chen Y, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning is associated with brain atrophy: a longitudinal study in nondemented older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31031615/

Sergott RC, Raji A, Kost J, Sur C, Jackson S, Locco A, et al. Retinal optical coherence tomography metrics are unchanged in verubecestat Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trial but Correlate with Baseline Regional Brain Atrophy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;79:275–87. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33252075/.

Galvin JE, Kleiman MJ, Walker M. Using optical coherence tomography to screen for cognitive impairment and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;84:723–36. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34569948/.

Zhao A, Fang F, Li B, Chen Y, Qiu Y, Wu Y, et al. Visual abnormalities associate with hippocampus in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33551787/

Hu Z, Wang L, Zhu D, Qin R, Sheng X, Ke Z, et al. Retinal alterations as potential biomarkers of structural brain changes in Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum Patients. Brain Sci. 2023;13:460. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36979270/.

Marquié M, García-Sánchez A, Alarcón-Martín E, Martínez J, Castilla-Martí M, Castilla-Martí L, et al. Macular vessel density in the superficial plexus is not associated to cerebrospinal fluid core biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: The NORFACE cohort. Front Neurosci. 2023;17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36908784/

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants from the FACEHBI and BIOFACE studies. We thank the investigators from Life Molecular Imaging for providing the Florbetaben compound and Topcon for its reliability as technological partnership.

The FACEHBI study group: Alllué JA1, Appiani F2, Ariton DM2, Berthier M3, Bojayrin U2, Buendia M2, Bullich S4, Campos F5, Castillo S1, Cañabate P2,6, Cañada L2, Cuevas C2, Diego S2, Espinosa A2,6, Gailhajenet A2, Guitart M2, Ibarria, M2, Lafuente A2, Lleonart N2, Lomeña F5, Martín E2, Moreno M2, Morera A2, Montrreal L2, Niñerola A5, Nogales AB2, Núñez L7, Orellana A2,6, Ortega G2,6, Páez A7, Pancho A2, Pelejà E2, Pérez-Martínez E4, Pérez-Grijalba V1, Pascual-Lucas M1, Perissinotti A5, Preckler S2, Ricciardi M2, Roé-Vellvé N4, Romero J1, Ramis MI2, Rosende-Roca M2, Sarasa M1, Seguer S2, Stephens AW4, Terencio J1, Torres M7, Vargas L2.

1Araclon Biotech-Grífols. Zaragoza, Spain.

2Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona – Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC), Spain.

3Cognitive Neurology and Aphasia Unit (UNCA). University of Malaga.

4Life Molecular Imaging GmbH, Berlin, Germany.

5Servei de Medicina Nuclear, Hospital Clínic i Provincial, Barcelona, Spain.

6CIBERNED, Center for Networked Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases, National Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

7Grifols®.

The BIOFACE study group: Appiani F,1 Ariton DM,1 Bojayrin U,1 Buendía M,1 Calvet A,1 Castillón MJ,1 Cañabate P,1 Cañada L,1 Cuevas C,1 de Rojas I,1 Diego S,1 Espinosa A,1,2 Gailhajenet A,1 Guitart M,1 Ibarria, M,1 Lafuente A,1 Lleonart N,1 Martín E,1 Moreno M,1 Morera A,1 Montrreal L,1 Nogales AB,1 Orellana A,1,2 Ortega G,1,2 Pancho A,1 Preckler S,1 Ricciardi M,1 Ramis MI,1 Rosende-Roca M,1 Seguer S,1 Vargas L1.

1Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona. Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain.

2CIBERNED, Center for Networked Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases, National Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

3Departament de Diagnòstic per la Imatge. Clínica Corachan, Barcelona, Spain

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study will be made available by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the AMYPAD project. As such, the investigators within AMYPAD contributed to the design and implementation of AMYPAD and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of AMYPAD contributors can be found at: https://amypad.eu/partners/.

Funding

This project has received funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) Acción Estratégica en Salud, integrated in the Spanish National RCDCI Plan and financed by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER—Una manera de hacer Europa) grant PI19/00335 awarded to MM, grant PI17/01474 awarded to MB, and grants AC17/00100, PI19/01301, PI22/01403, and PMP22/00022 awarded to AR. This project is also funded by the European Union Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) Multinational research projects on Personalized Medicine for Neurodegenerative Diseases/Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant AC19/00097 awarded to AR. IdR received funding support from the ISCIII grant FI20/00215. AC received funding support from the ISCIII grant Sara Borrell (CD22/00125) and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Proyectos de Generación de Conocimiento grant PID2021-122473OA-I00. PGG was supported by CIBERNED employment plan CNV-304-PRF-866.

The FACEHBI study was supported with funds from Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona, Grifols, Life Molecular Imaging, Araclon Biotech, Alkahest, Laboratorio de análisis Echevarne, and IrsiCaixa supported. The FACEHBI study was part of the AMYPAD-PNHS project, which received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No 115952. This Joint Undertaking received the support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA. This communication reflects the views of the authors and neither IMI nor the European Union and EFPIA are liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AGS, MM, AR, LT and MB designed the study. AGS and and MM prepared the databases and performed the data curation. AGS performed the statistical analysis under the supervision of SV. AGS and MM wrote the original draft. JPT, AS, EEA, APC, MA, VP, JM, NA, AV, MGC, JG and MAT were involved in the acquisition of data. OSG, IdR, AC, PGG, RP, CO, MC, FGG, AV, MGC, JG, MAT, MCM and LCM performed the biomarker and imaging analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings, critical review of the manuscript, approval of the final manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The FACEHBI-2 protocol (which includes study v5) and BIOFACE protocol were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic i Provincial in Barcelona, Spain. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MB has consulted for Araclon, Avid, Grifols, Lilly, Nutricia, Roche, Eisai and Servier. She received fees from lectures and funds for research from Araclon, Biogen, Grifols, Nutricia, Roche and Servier. She reports grants/research funding from Abbvie, Araclon, Biogen Research Limited, Bioiberica, Grifols, Lilly, S.A, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Laboratorios Servier, Nutricia SRL, Oryzon Genomics, Piramal Imaging Limited, Roche Pharma SA, and Schwabe Farma Iberica SLU, all outside the submitted work. She has not received personal compensations from these organizations. AR is member of scientific advisory board of Landsteiner Genmed and Grifols SA. AR has stocks of Landsteiner Genmed. MM has consulted for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. The rest of authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Multiple linear regression analyses of the association of clinical, demographic and biomarker variables with macular VD. Including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.05. Abbreviations: A: amyloid; APOE: apolipoprotein E; CI: confidence interval; VD: vessel density.

Additional file 2.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with hippocampal volume with adjusting factors. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviation: VD: vessel density.

Additional file 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with hippocampal volume without adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviation: VD: vessel density.

Additional file 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with ventricle volume with adjusting factors. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviation: VD = vessel density. Note: A log transformation was applied to the ventricles volume measures.

Additional file 5:

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with ventricles volume without adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviation: VD = vessel density. Note: A log transformation was applied to the ventricles volume measures.

Additional file 6.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with ADCS thickness with adjusting factors. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: ADCS: Alzheimer´s disease cortical signature; VD = vessel density.

Additional file 7.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the association of regional macular VD with ADCS thickness without adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: ADCS: Alzheimer´s disease cortical signature; VD = vessel density.

Additional file 8.

Logistic regression analysis of the interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating Fazekas categories. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; VD: vessel density.

Additional file 9.

Multivariate regression analysis of the interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating WMH volume. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: A: amyloid; V: vessel density.

Additional file 10.

Multivariate regression analysis of the interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating hippocampal volume. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: A: amyloid; VD: vessel density.

Additional file 11.

Multivariate regression analysis of the interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating ventricles volume. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: A: amyloid; VD: vessel density. Note: A log transformation was applied to the ventricles volume measures.

Additional file 12.

Multivariate regression analysis of the interaction of the A status and macular VD in discriminating ACDS thickness. Including age, sex, syndromic diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart disease, respiratory disease and smoking as adjusting factors. Significance was set up at p < 0.0125. Abbreviations: A: amyloid; ADCS: Alzheimer´s disease cortical signature; VD: vessel density.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Sánchez, A., Sotolongo-Grau, O., Tartari, J.P. et al. Macular vessel density in the superficial plexus is not a proxy of cerebrovascular damage in non-demented individuals: data from the NORFACE cohort. Alz Res Therapy 16, 42 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-024-01408-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-024-01408-9