Abstract

Background

There are few updated studies on the prevalence and management of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which could be underdiagnosed or undertreated. The COVID-19 pandemic may have worsened the deficiencies in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients. Electronic medical records (EMR) offer an opportunity to assess the impact and management of medical processes and contingencies in the population.

Objective

To estimate AD prevalence in Spain over a 6-year period, based on treated patients, according to usual clinical practice. Additionally, to describe the management of AD-treated patients and the evolution of that treatment during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Retrospective study using the Spanish IQVIA EMR database. Patients treated with donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine were included in the study. Annual AD prevalence (2015–2020) was estimated and extrapolated to the national population level. Most frequent treatments and involved specialties were described. To assess the effect of COVID-19, the incidence of new AD cases in 2020 was calculated and compared with newly diagnosed cases in 2019.

Results

Crude AD prevalence (2015–2020) was estimated at 760.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, and age-standardized prevalence (2020) was 664.6 (male 595.7, female 711.0). Monotherapy was the most frequent way to treat AD (86.2%), in comparison with dual therapy (13.8%); rivastigmine was the most prescribed treatment (37.3%), followed by memantine (36.4%) and donepezil (33.0%). Rivastigmine was also the most utilized medication in newly treated patients (46.7%), followed by donepezil (29.8%), although donepezil persistence was longer (22.5 vs. 20.6 months). Overall, donepezil 10 mg, rivastigmine 9.5 mg, and memantine 20 mg were the most prescribed presentations. The incidence rate of AD decreased from 148.1/100,000 (95% confidence interval [CI] 147.0–149.2) in 2019 to 118.4/100,000 (95% CI 117.5–119.4) in 2020.

Conclusions

The obtained prevalence of AD-treated patients was consistent with previous face-to-face studies. In contrast with previous studies, rivastigmine, rather than donepezil, was the most frequent treatment. A decrease in the incidence of AD-treated patients was observed during 2020 in comparison with 2019, presumably due to the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on both diagnosis and treatment. EMR databases emerge as valuable tools to monitor in real time the incidence and management of medical conditions in the population, as well as to assess the health impact of global contingencies and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia, mostly due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is one of the greatest global challenges for health and social care in the twenty-first century [1]. As AD evolves, the patient undergoes a progressive deterioration of cognitive abilities that leads to a gradual loss of autonomy, usually accompanied by significant affective and behavioral disturbances [2]. In fact, dementia is the main cause of institutionalization in the elderly [3] and is being increasingly reported as a predictor of death [4]. In developed countries, the number of older people with dementia is expected to rise more than double in the next 25 years [5].

Evidence indicates, and specialists agree, that underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients with dementia are common, with serious consequences on patients’ functional capacity and quality of life [6,7,8]. To provide AD patients with adequate care, it is essential to proceed with timely detection, accurate diagnosis, and evidence-based management [9]. In that enterprise, professionals in health and social care fields should efficiently participate and interact with a common aim of maintaining patient functionality and quality of life, as well as reducing the caregivers’ burden [10].

With regard to the pharmacological treatment for AD, there are currently two types of marketed specific drugs: (a) cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), i.e., donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, and (b) a non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, i.e., memantine. For mild to moderate phases of AD, it is recommended that one of the three available ChEIs be used, whereas memantine is recommended, alone or in combination, in patients with moderate and severe AD [11]. These medications provide temporary symptomatic stabilization as well as a reduction in long-term mortality [12].

In Spain, as in many other countries, there is a deficit in the response to the needs of health and social services for the prevention, treatment, and care of Alzheimer’s dementia [13,14,15,16]. Due to these uncovered needs, a comprehensive plan was envisioned and published with the objective of promoting timely Alzheimer’s diagnosis and optimal management. Awareness programs were recommended for health professionals, focusing on the detection of signs and symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases and on the establishment of criteria-based, agile processes for patient referral to specialists from primary care [17].

The 2019 pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), greatly stressed the healthcare systems worldwide. Since then, people with dementia have been consistently reported as the most vulnerable to the negative acute and post-acute consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection [18, 19]. Among the significant changes that AD patients and healthcare professionals faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, many dementia consultations were withheld to either reduce transmission or redirect healthcare staff toward care for COVID-19 patients [20]. This likely led to the postponement of diagnosis and prescription in patients suffering from incipient dementia, thus increasing the anguish of the patient and the burden of the caregiver [21].

The primary objective of the study was to estimate the AD prevalence in Spain, in a 6-year period (i.e., 2015–2020), based on treated patients, according to usual clinical practice. Secondary objectives included (a) to describe the management of AD-treated patients (i.e., prescribed medications, average duration per treatment, and level of attended care specialization) and (b) to describe the evolution of AD treatment during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective, longitudinal, observational study. Patients’ data were extracted from the Spanish IQVIA Electronic Medical Records (EMR) database. This database contains the anonymized health records of patients from three Spanish regions, collected through 8000 office-based primary and secondary care physicians belonging to the public health system and covering approximately 3.0% of the Spanish population. The EMR population is comparable to the national population in age and sex (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

For this study, AD was defined as the prescription of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine, without a number of prescription limits. There were no age or sex restrictions for patient inclusion. Patient characteristics (age, gender), comorbidities (i.e., diagnostic code according to the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision [ICD-9] and registration date), healthcare contacts (i.e., specialty and visit date), and prescriptions were collected. To qualify for a prescription, the medication had to be prescribed by the physician and dispensed in the pharmacy office. The analysis covered the period between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2020, which was adapted according to database characteristics and specific study objectives.

The study protocol (version 0.1, May 11, 2021), with code ZAM-ALZ-2021–01, was approved by the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Institutional Review Board (IRB), on May 21, 2021(meeting #10/2021).

Statistical analysis

For the description of categorical variables, number, percentage of cases, and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) were obtained.

Prevalence

Annual AD prevalence was estimated by selecting the total number of Alzheimer’s patients that had at least one prescription of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine during the year and extrapolating to the national population level, using Spanish population data provided by the National Institute for Statistics (NIS). Although data collection started in 2013, full harmonization between the three covered geographical regions was not achieved until 2015. For that reason, the period 2013–2020 was used for total patient detection, while the period 2015–2020 was selected to present annual and pooled prevalence.

It should be noted that the selection of treated Alzheimer’s patients was carried out on the base of patients treated annually, and from this total volume, those patients were defined as active. Hence, an active patient was prescribed annually with donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine. Then, the number of treated patients per year was extrapolated at the national level.

The period prevalence was estimated by dividing the mean number of cases obtained over the observation period (i.e., 2015–2020) by the population at the study’s midpoint on Donaldson’s epidemiology method [22]:

Age-standardized AD prevalence was obtained at the end of the study period (i.e., year 2020) using the European Standard Population 2013 (ESP 2013). In addition, the crude prevalence was obtained for the population aged 70 or more to propitiate comparison with previous investigations.

Incidence

The number of new AD-treated cases extrapolated from the database in 2019 and 2020 was utilized to estimate how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the diagnosis of AD.

Comorbidities

The comorbidity analysis methodology was based on an extraction of all symptoms and diagnoses registered between 2013 and 2020 for patients previously identified as AD-prevalent, considering prevalent patients treated with donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine at any time during that period.

Patient management

With the purpose of describing the management of AD-treated patients (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine), the following endpoints were considered:

-

Number and percentage of patients that received treatment in 2020. This was calculated based on the monthly average. Monthly average was chosen as an adequate method to capture treatment diversity and modifications (i.e., treatment addition or abandonment, dose adjustment) during disease. Monthly treated patients were calculated based on the most representative treatment of each patient each month, which means the treatment received the highest number of days in that month. For a given treatment, the annual frequency was obtained by dividing the number of patients receiving that treatment as the most frequent (according to the annual average of the monthly days of treatment) by the number of analyzed (i.e., database active) patients.

$$\mathrm{Annual\, frequency }=\frac{Number\, of\, patients\, receiving\, \left(most\, frequently\right)\, a\, given\, treatment}{Number\, of\, active\, patients}\times 100$$ -

Number and percentage of patients who initiated donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine as treatment and maintained treatment or switched to a different medication. For this analysis, we selected those patients that initiated treatment between 2014 and 2017 and completed a follow-up period of 36 months. Treatment initiation was defined as the absence of (ChEI or memantine) prescription in the 12 months prior to the first prescription observed in the 2014–2017 period. Patients that switched treatment were defined as those who stopped using any treatment for AD and started any other treatments, including combinations. Additionally, the average duration per treatment (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine) was analyzed and expressed in months (mean duration).

-

Number and percentage of patients receiving the different presentations of the target medications (i.e., donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine) from January 2015 to December 2020. As treatments can be prescribed in monotherapy or as combination therapy, and a wide range of presentations are available in the current national market, the top ten, most used treatments were considered for the analysis. The mean number of treated patients’ monthly was obtained for every year, according to the selected treatment.

-

Level of attended care specialization. The involved medical specialties were described for those patients that initiated treatment between 2014 and 2017 and completed a follow-up period of 36 months.

Impact of COVID-19

Newly diagnosed AD patients were defined as patients treated for the first time with any AD treatment (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine), in 2019 and 2020.

Results

Study population

A total of 5001 prevalent AD patients were identified during the complete (i.e., 2013–2020) study period; of them, 64.1% were female and 35.9% were male. Age distribution was as follows: 0–59 years (0.8%), 60–69 years (4.6%), 70–79 years (28.4%), 80–89 years (55.8%), and ≥ 90 years (10.4%).

Prevalence of AD

The prevalence of AD for the 2015–2020 period in Spain was estimated at 760.5 per 100,000 inhabitants (Table 1). Patients who received medications for treating AD were considered from the year 2015, as shown in Table 1. In general terms, the number of treated patients increased over recent years, particularly from 2015 to 2017. Overall, comparing 2015 and 2020, AD prevalence rose 1.48% (339,770 versus 344,805, respectively). However, from 2017 to 2020, the number of treated patients was somewhat lower (365,657 versus 344,805, respectively, 5.70% decrease).

Crude and age-standardized prevalence is presented, for the year 2020, in Table 2. We observed an overall standardized prevalence of 664.6 (95% CI 662.4–666.8) of AD cases per 100,000 population in Spain. When age-standardized prevalence was estimated according to sex (Table 2), the prevalence in women was consistently higher than in men (711.0 per 100,000 women in the population [95% CI 708.1–714.0] versus 595.5 per 100,000 men in the population [95% CI 592.4–599.0]). In the sub-analysis of people aged 70 or more, the crude prevalence of AD was 4,801.6 (95% CI 4,773.5–4829.7), being the corresponding figures for women and men 5331.3 (95% CI 5001.2–5,361.4) and 4061.5 (95% CI 4035.3–4087.7), respectively. Age-specific AD prevalence and age-standardized cases, in the total population and stratified by sex, are listed in Additional file 1: Tables S1-S3.

Comorbidities

As expected, a wide range of comorbidities was associated with AD patients (Fig. 1). A percentage of 55.1% of patients were reported as having between 9 and 12 comorbidities, that being the most prevalent group of the categories; 32.9% of patients presented 5–8 comorbidities and the lowest percentage corresponded to the most extreme groups (6.0% of patients had 0–4 comorbidities and 6.0% of patients presented more than 12 comorbidities. The most prevalent comorbidity was sleep disturbance (codes 780–789, 91.6% of patients), followed by hypertensive disease (codes 401–405, 63.8%) and neurotic, personality, and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (codes 300–316, 63.2%) (see Additional file 1: Fig. S2 for a detailed description of the registered comorbidities).

Management of patients with AD in Spain

Current treatment for AD

According to our results, in 2020, rivastigmine was the most recurrent drug for treating AD in Spain, followed by donepezil and memantine. As Fig. 2 describes, monotherapy was the most frequent way to treat AD, at 3368 (86.2%), in comparison with combination therapy, at 538 (13.8%) patients. Considering patients on monotherapy, out of 3906 monthly treated patients, 1190 (30.5%) were treated with rivastigmine, 1073 (27.5%) received donepezil, and 941 (24.1%) patients were under memantine treatment. Galantamine was received by 164 (4.2%) of patients. The rest of the patients were receiving combination therapy, rivastigmine, and memantine being the most common combination among the patients, 266 (6.8%), followed by the combination of donepezil and memantine, 216 (5.4%) of patients. Galantamine and memantine combination in the treatment of Alzheimer’s corresponded to a rather low percentage of patients, 56 (1.4%).

According to the EMR database, during a follow-up period of 36 months, a total of 4747 (100%) patients received a first-line treatment for a mean duration of 21.1 months. Of these patients, 1272 (26.7%) switched to an alternative therapy (second-line treatment), the mean duration of which was 12.7 months. Finally, a small percentage of patients, 511 (10.7%), who received a second-line treatment, switched to third-line therapy. The most frequent first-line treatment was rivastigmine (46.2%), followed by donepezil (29.5%), memantine (17.8%), and galantamine (5.4%). Treatment initiation with combination therapy (i.e., ChEI and memantine) was anecdotal (~ 1%). For a clear and detailed description of treatment evolution, the patients who received donepezil and memantine as first-line, as well as the subsequently prescribed treatment lines, are shown in Fig. 3, while the monitoring of patients who received rivastigmine and galantamine as first-line treatment is represented in Fig. 4.

For donepezil as the first line, the mean duration of treatment was 22.5 months. As shown in Fig. 3, 419 (29.9%) of those patients who received donepezil switched to another treatment alternative during the observation period: 203 (14.5%) received a combination of donepezil and memantine as second-line treatment for a mean duration of 10.5 months, and 100 (7.2%) received memantine as monotherapy, for 13.5 months. With regard to memantine treatment, 847 (17.8%) patients received it as the first line for a mean duration of 20.6 months. As expected, the number of patients that changed from memantine to a second-line treatment was low (9.8%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 4 describes the treatment flow of those patients who were administered rivastigmine, 2193 (46.2%), or galantamine, 258 (5.4%), as first-line treatment, as well as the progression to alternative treatments. The mean duration of rivastigmine treatment (20.6 months) was the same as that reported for memantine (Fig. 3) and close to galantamine (20.1 months). A total of 629 (28.7%) rivastigmine-treated patients switched to a second-line treatment, being a combination of memantine and rivastigmine the most frequent alternative therapy in this group of patients, 279 (12.7%), with a mean treatment duration of 10.3 months (Fig. 4). More than half of these patients, 154 (55.2%), switched to third-line therapy, memantine being the most prescribed drug, 93 (33.2%).

With regard to galantamine first-line treated patients, 94 (36.4%) of them switched to second-line treatment, a combination of galantamine and memantine being the most prescribed, at 47 (18.2%). However, the most durable second-line treatments for this group of patients were memantine (mean duration, 16.7 months) and rivastigmine (mean duration, 16.6 months), both as monotherapy (Fig. 4).

Treatment dosage

The most prevalent treatment prescriptions, as well as the mean number and percentage of patients that received the described prescription monthly, from 2015 to 2020, are presented in Table 3. If we observe the total number of patients who received a specific treatment, we can see an increasing tendency toward treatment prescriptions over the years, which ranges from a mean number of 3592 patients in 2015 to 3910 patients in 2020. However, the mentioned growth was not entirely linear, as in 2018 and 2020, small decrease in the mean number of total treated patients was observed (Table 3).

According to our results, donepezil 10 mg, rivastigmine 9.5 mg, and memantine 20 mg would be largely the most prescribed treatment presentations in Spain, with global shares of 19–20% of total prescriptions. Focusing on the evolution of the described treatments from 2015 to 2020, we noticed that donepezil (10 mg and 5 mg), rivastigmine 13.3 mg, and memantine 10 mg were increased by 3–5% (absolute increase), and rivastigmine 9.5, galantamine 24 mg, and the combination of memantine 20 mg and rivastigmine 9.5 mg were decreased by 2–6% (absolute decrease), while memantine 20 mg, rivastigmine 4.6, and the combination of memantine 20 mg and donepezil 10 mg remained essentially unchanged (Table 3).

Patient flow chart according to specialty involved in diagnosis and monitoring of AD-treated patients

Neurology was the main specialty involved in the diagnosis of AD, with 3710 (78.2%) patients diagnosed and followed for a mean time of 14.3 months. A total of 1037 (21.8%) patients were diagnosed by other medical specialties, which included internists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, and general practitioners (GPs). Patients diagnosed by non-neurology medical specialties were monitored by that specialty during a mean time of 13.2 months.

According to Fig. 5, follow-up of 60.1% (2227) of patients diagnosed by a neurologist was managed by GP, after a mean time of 12.9 months, while 34.9% (1297) of patients continued to be followed by neurologists. As for the patients diagnosed by non-neurology specialty, switch to neurologist was the most frequent change, which occurred in 40.9% (423) of patients, while 40.5% (421) did not change specialist. A second specialty switch (third step) was observed in more than half of patients, most frequently occurring between neurologist and GP: after a mean time of 8.1 months, 62.6% (1392) of patients that were followed by GP were switched to neurologist, while 52.7% (223) of patients that were followed by neurologist were switched to GP, after a mean time of 10.0 months (data of switches between other specialties are not shown).

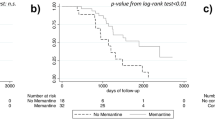

Impact of COVID-19 on Alzheimer’s diagnosis and treatment

The annual incidence of AD was estimated at 148.1 patients per 100,000 population (95% CI 147.0–149.2) in 2019, while the incidence estimation for the year 2020 was 118.4 patients per 100,000 population (95% CI 117.5–119.4). Hence, a significant decrease in the estimated incidence of AD, according to newly reported treated patients, was observed in 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4).

Figure 6 shows the proportion of newly diagnosed AD patients by sex in 2019 and 2020 years. For both years, over half of new AD cases occurred among females. However, there was a decrease in the proportion of female patients diagnosed during 2020 (60.9%) in comparison with 2019 (75.7%), leading to an increase in the frequency of new male AD cases in 2020 (39.1%) versus 2019 (24.3%).

Discussion

We interrogated a national EMR database to estimate the prevalence of patients treated for AD, to describe the pharmacological and specialty management, and to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the provision of healthcare in Spain. According to the presented results, the age-standardized prevalence of AD during the 2015–2020 period was estimated at 760.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, which falls within the 700–799 prevalence interval obtained in the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) Study [23]. That similarity of results was unexpected, since non-AD dementias (vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal dementias, etc.) were included in the GBD Study. Moreover, a recent study, also built on EMR data, found incidence and prevalence estimations of AD slightly lower than those obtained in face-to-face studies [24]. Nevertheless, a reanalysis of face-to-face dementia surveys, conducted in the population aged 70 and over, age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of AD ranged from 2.6 to 7.7% [25], which is consistent with our age-adjusted prevalence of 4.8%, obtained for the same group of age. We could speculate that, in our investigation, possible underestimation of AD prevalence due to the lack of diagnosis or treatment was counter-balanced by the prescription of ChEI and memantine to non-AD dementia patients, eventually providing a valid estimation of AD prevalence, incidence, and evolution. As in previous face-to-face studies [25], we obtained higher crude and age-standardized AD prevalence in women than in men, which gives further support to the utilized methodology.

The comorbidity of our “real-world” AD patients was remarkably high, with almost two out of three patients (61.1%) displaying nine or more associated medical conditions. That is not surprising since also two each of every three patients (66.2%) had 80 or more years of age. These results point to the need to investigate the potential medical and psychiatric modifiers of the clinical and biological course of AD, as well as how comorbidities can alter treatment response and quality of life, especially in older patients [26].

Rivastigmine, memantine, and donepezil, alone or in combination, were the most frequently used AD medications, which were prescribed to 94.4% of patients, while galantamine was only utilized in 5.6% of patients. Preponderance of donepezil over galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine was reported in a retrospective study of EMR that analyzed GPs’ dementia patients and covered the period from 2005 to 2015 [27]. Similar results were obtained in a recent multinational study based on record form completion of AD patients, conducted by GPs, neurologists, geriatricians, and psychiatrists [28]. In contrast, we found a similar frequency of prescription of donepezil, rivastigmine, and memantine, which could be due to more advanced dementia stage or sample contamination with non-AD patients. Regarding ChEIs, reasons to favor the use of donepezil and rivastigmine, versus galantamine, may be related to ease of use and specific clinical effects, such as improvement of psychotic symptoms [29].

Overall, monotherapy prevailed over dual therapy (86.2% vs. 13.8%), which is consistent with previous investigations, although we obtained a slightly higher prevalence of combined treatment (13.8% vs. 6.0%), mostly due to the appearance of rivastigmine and memantine combination [28]. These low figures of dual therapy suggest suboptimal treatment, considering the good tolerance, prolonged clinical benefits, and institutional and expert recommendations favoring the use of ChEI and memantine combination [11, 30, 31].

With regard to the first-line treatment that AD patients received in Spain, ChEIs were the choice in most patients (81.1%), again consistent with the existing studies and guidelines, reporting very mild or unclear effects of memantine in mild AD [32]. However, in contrast with previous studies, rivastigmine was the most prescribed monotherapy (46.2%), followed by donepezil (29.5%), memantine (17.8%), and galantamine (5.4%). In a study of Medicare beneficiaries that initiated AD treatment during the period of 2001–2003, donepezil was the most frequent drug (62.8%), followed by galantamine (17.2%) and rivastigmine (20.1%) [33]. In a Canadian population-based study conducted during the period of 2009–2013, donepezil was also the most frequent medication (59%), followed by rivastigmine (22%) and galantamine (19%) [34]. A Korean study analyzing data of the 2009–2019 period obtained a prevalence of 48.8% (donepezil), 18.1% (memantine), 9.0% (rivastigmine), and 5.7% (galantamine) [35]. The higher frequency of use of rivastigmine observed in our investigation could be due to the inclusion of non-AD patients, particularly patients with Lewy body or Parkinson’s disease dementia [36] but could also indicate a new trend of prescription in real-world patients—where dementia etiology is not always clear—that favors the use of medications that offer a wide range of target symptoms, doses, and presentations [37, 38].

Despite the higher frequency of rivastigmine prescription, donepezil showed slightly better persistence: 37.8% of patients that started on donepezil maintained the treatment (versus 31.0% of patients that initiated treatment with rivastigmine), and the mean time from treatment initiation to switch was 22.5 months for donepezil (versus 20.6 months for rivastigmine). In previous studies of new ChEI users, rivastigmine was also associated with shorter mean persistence and higher switch rate, compared to donepezil [34, 35]. These results should be taken cautiously though, since the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics (age, comorbidities, neuropsychiatric symptoms, etc.) were not controlled.

Treatment initiation by neurologists, along with patient transfer between GP and neurologist, was the most common specialty scenario, albeit a relevant number of patients were managed by other specialties. That is consistent with previous studies conducted in Spain [39] but not in other countries, where management by GP prevailed and the participation of other specialties was less frequent [40]. Clearly, in a context of varied region and country-specific scenarios, EMR studies may help to inform administrations and providers to achieve the so-needed global and coordinated care for people with dementia and their families [11, 17, 41].

The COVID-19 pandemic changed our lives profoundly in a very short time, provoking devastating effects on people with dementia [21]. As the number of professionals was reduced and most face-to-face consultations were canceled, medical efforts were focused on the symptomatic relief of the affective and behavioral symptoms of the already diagnosed patients, as well as on the advice of their relatives, usually through teleconsultations [19]. Not surprisingly, the incidence of AD-treated patients was decreased from 148 patients per 100,000 of the Spanish population in 2019 to 118 patients per 100,000 in 2020, possibly due to lack of diagnosis. This is concerning, as COVID-19 lockdown and SARS-CoV-2 infection were shown to produce and aggravate cognitive symptoms, presumably leading to a higher incidence of dementia [42, 43]. The impact of COVID-19 on new AD diagnoses was more pronounced in women than in men, possibly because the greater age and fragility of the former prevented diagnosis and AD-specific treatment. In a recent investigation, older age and female sex were associated with decreased dementia diagnosis during the 2020 pandemic year [44]. Of note, we did not observe a significant decrease in the mean number of treated patients (3954 patients in 2019 to 3910 in 2020, 1.1% decrease), which suggests that the existing treatments were maintained.

The present study had several limitations. Firstly, AD prevalence was estimated based on medication prescription, rather than physician’s etiological diagnosis. Hence, the prevalence might have been underestimated due to not diagnosed or treated patients, but also overestimated, due to treatment of non-AD dementia patients [45]. Nonetheless, our prevalence results were congruent with previous face-to-face investigations [25] and should be valid regarding the evolution of AD diagnosis and treatment during the study period, as well as the COVID-19 impact. Secondly, the lack of etiological diagnosis and analysis adjustment for key control variables (i.e., age and comorbidities) prevented a more complete understanding of patient management. Thirdly, since data collection was finished at the end of the first pandemic year, the consequences of COVID-19 in dementia diagnosis and treatment could not be further described. A recent study demonstrated a lack of global rebound of new dementia cases during 2021, perhaps due to the dramatic increase in mortality suffered by very aged people, while dementia cases ascertained in hospitals and among individuals with multiple comorbidities were higher than expected [46]. Clearly, continued population-based monitoring is needed to fully understand the long-term effects of post-acute SARS-CoV-2 in people with Alzheimer and other dementias.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of IQVIA.

References

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6.

Soria Lopez JA, González HM, Léger GC. Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:231–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00013-3.

Agüero-Torres H, von Strauss E, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Institutionalization in the elderly: the role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):795–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00371-1.

Kurichi JE, Kwong PL, Xie D, Bogner HR. Predictive indices for functional improvement and deterioration, institutionalization, and death among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. PM R. 2017;9(11):1065–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.04.005.

Wittenberg R, Hu B, Jagger C, et al. Projections of care for older people with dementia in England: 2015 to 2040. Age Ageing. 2020;49(2):264–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz154.

Rountree SD, Chan W, Pavlik VN, Darby EJ, Siddiqui S, Doody RS. Persistent treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine slows clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2009;1(2):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt7. Published 2009 Oct 21.

Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1131–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4377-y.

Rodríguez-Gómez O, Rodrigo A, Iradier F, Santos-Santos MA, Hundemer H, Ciudin A, et al. The MOPEAD project: advancing patient engagement for the detection of “hidden” undiagnosed cases of Alzheimer’s disease in the community. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(6):828–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.02.003.

Atri A. The Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum: diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(2):263–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.009.

Heintz H, Monette P, Epstein-Lubow G, Smith L, Rowlett S, Forester BP. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(3):320–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidelines. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers; NICE. 2018. https://www.guidelines.co.uk/mental-health/nice-dementiaguideline/454244.article Accessed 31 May 2022

Truong C, Recto C, Lafont C, Canoui-Poitrine F, Belmin JB, Lafuente-Lafuente C. Effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on mortality in patients with dementia: a systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials [published online ahead of print, 2022 Sep 12]. Neurology. 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201161

Bond J, Stave C, Sganga A, O’Connell B, Stanley RL. Inequalities in dementia care across Europe: key findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005;146:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-504x.2005.00480.x.

Jones RW, Mackell J, Berthet K, Knox S. Assessing attitudes and behaviours surrounding Alzheimer’s disease in Europe: key findings of the Important Perspectives on Alzheimer’s Care and Treatment (IMPACT) survey. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(7):525–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-010-0263-y.

Martínez-Lage P, Martín-Carrasco M, Arrieta E, Rodrigo J, Formiga F. Mapa de la enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias en España. Proyecto MapEA [Map of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Spain. MapEA Project]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2018;53(1):26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2017.07.006. Article in Spanish.

Lleó A. [Alzheimer’s disease: an ignored condition]. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150(11):432–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2017.10.028. Article in Spanish.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Plan Integral de Alzheimer y Otras Demencias (2019–2023); Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social 2019; https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/docs/Plan_Integral_Alhzeimer_Octubre_2019.pdf Accessed 31 May 2022

Mok VCT, Pendlebury S, Wong A, Alladi S, Au L, Bath PM, et al. Tackling challenges in care of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias amid the COVID-19 pandemic, now and in the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(11):1571–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12143.

Benaque A, Gurruchaga MJ, Abdelnour C, Hernández I, Cañabate P, Alegret M, et al. Dementia care in times of COVID-19: experience at Fundació ACE in Barcelona. Spain J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(1):33–40. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200547.

Cuffaro L, Di Lorenzo F, Bonavita S, Tedeschi G, Leocani L, Lavorgna L. Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: a necessary digital revolution. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(8):1977–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04512-4.

Numbers K, Brodaty H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(2):69–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00450-z.

Donaldson LJ, Rutter PR. Donaldsons’ essential public health. 4th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2017.

GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):88–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4.

Ponjoan A, Garre-Olmo J, Blanch J, Fages E, Alves-Cabratosa L, Martí-Lluch R, et al. Is it time to use real-world data from primary care in Alzheimer’s disease? Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00625-2.

de Pedro-Cuesta J, Virués-Ortega J, Vega S, et al. Prevalence of dementia and major dementia subtypes in Spanish populations: a reanalysis of dementia prevalence surveys, 1990–2008. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-9-55.

Maciejewska K, Czarnecka K, Szymański P. A review of the mechanisms underlying selected comorbidities in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Rep. 2021;73(6):1565–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00293-5.

Donegan K, Fox N, Black N, Livingston G, Banerjee S, Burns A. Trends in diagnosis and treatment for people with dementia in the UK from 2005 to 2015: a longitudinal retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(3):e149–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30031-2.

Podhorna J, Winter N, Zoebelein H, Perkins T. Alzheimer’s treatment: real-world physician behavior across countries. Adv Ther. 2020;37(2):894–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01213-z.

Cummings J, Emre M, Aarsland D, Tekin S, Dronamraju N, Lane R. Effects of rivastigmine in Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without hallucinations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(1):301–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-1362.

Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, Ritchie C, Baldwin A, Barber R, et al. Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):893–903. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1106668.

Gauthier S, Molinuevo JL. Benefits of combined cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine treatment in moderate-severe Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(3):326–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.11.005.

McShane R, Westby MJ, Roberts E, Minakaran N, Schneider L, Farrimond L, et al. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD003154. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub6. Published 2019 Mar 20.

Mucha L, Shaohung S, Cuffel B, McRae T, Mark TL, Del Valle M. Comparison of cholinesterase inhibitor utilization patterns and associated health care costs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(5):451–61. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.5.451.

Fisher A, Carney G, Bassett K, Dormuth CR. Tolerability of cholinesterase inhibitors: a population-based study of persistence, adherence, and switching. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(3):221–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0438-x.

Byun J, Lee DY, Jeong CW, Kim Y, Rhee HY, Moon KW, et al. Analysis of treatment pattern of anti-dementia medications in newly diagnosed Alzheimer’s dementia using OMOP CDM. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4451. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08595-1. Published 2022 Mar 15.

Kandiah N, Pai MC, Senanarong V, Looi I, Ampil E, Park KW, et al. Rivastigmine: the advantages of dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase and its role in subcortical vascular dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:697–707. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S129145.

Sicras-Mainar A, Vergara J, Leon-Colombo T, Febrer L, Rejas-Gutierrez J. Retrospective comparative analysis of antidementia medication persistence patterns in Spanish Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine. Rev Neurol. 2006;43(8):449–53. Article in Spanish.

Matsuzono K, Sato K, Kono S, Hishikawa N, Ohta Y, Yamashita T, et al. Clinical benefits of rivastigmine in the real world dementia clinics of the Okayama Rivastigmine Study (ORS). J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(3):757–63. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150518.

Gil P, Ayuso JL, Marey JM, Antón M, Quilo CG. Variability in the diagnosis and management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease: results from the GALATEA multicentre, observational study. Clin Drug Investig. 2008;28(7):429–37. https://doi.org/10.2165/00044011-200828070-00004.

Koller D, Hua T, Bynum JP. Treatment patterns with antidementia drugs in the United States: Medicare cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1540–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14226.

National Alzheimer’s Project Act. USA: 2011. Public Law 111 -375-Jan 4 2011

Tsapanou A, Papatriantafyllou JD, Yiannopoulou K, Sali D, Kalligerou F, Ntanasi E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with mild cognitive impairment/dementia and on their caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(4):583–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5457.

Xia X, Wang Y, Zheng J. COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease: how one crisis worsens the other. Transl Neurodegener. 2021;10(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-021-00237-2. Published 2021 Apr 30.

Axenhus M, Schedin-Weiss S, Tjernberg L, Wimo A, Eriksdotter M, Bucht G, Winblad B. Changes in dementia diagnoses in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):365. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03070-y.

Schliep KC, Ju S, Foster NL, Smith KR, Varner MW, Østbye T, Tschanz JT. How good are medical and death records for identifying dementia? Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(10):1812–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12526.

Jones A, Bronskill SE, Maclagan LC, Jaakkimainen L, Kirkwood D, Mayhew A, Costa AP, Griffith LE. Examining the immediate and ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population-based estimates of dementia: a population-based time series analysis in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e067689. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067689.

Acknowledgements

Arantxa Avilés (Zambon), Héctor Gutiérrez (IQVIA), and María Targhetta (IQVIA) provided technical help and support.

Funding

This study was promoted and funded by Zambon España. Zambon provided logistic support to the researchers but did not have a major role in the design of the study nor in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O. participated in the study design, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. C.C.P. and J.F. participated in the study design, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and substantively reviewed the manuscript. P.S.J., G.G.R., F.V., P.M.L., and M.B. participated in the study design and substantively reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol (version 0.1, May 11, 2021), with code ZAM-ALZ-2021–01, was approved by the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Institutional Review Board (IRB), on May 21, 2021 (meeting #10/2021).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Age-standardized prevalence of AD in total Spanish population. AD: Alzheimer’s disease. Table S2. Age-standardized prevalence of AD in female Spanish population. AD: Alzheimer’s disease. Table S3. Age-standardized prevalence of AD in male Spanish population. AD: Alzheimer’s disease. Figure S1. Comparison between EMR and national population. *EMR population is represented as bars and national population (year 2020) as overlay shadow. EMR: Electronic Medical Records; INE: National Institute of Statistics. Figure S2. Groups and frequency of comorbidities in AD-prevalent patients (2013-2020 period, n=5,001 prevalent patients).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Olazarán, J., Carnero-Pardo, C., Fortea, J. et al. Prevalence of treated patients with Alzheimer’s disease: current trends and COVID-19 impact. Alz Res Therapy 15, 130 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01271-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01271-0