Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the diagnostic value of plasma β-amyloid (Aβ) seeding activity measured using a newly developed instrument to distinguish Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from other forms of dementia.

Methods

Seventy-nine AD patients, 64 non-AD dementia (NADD) patients, and 75 cognitively normal (NC) subjects were recruited in the study. To measure the levels of Aβ seeding activity in the plasma samples, we have developed an AD-seeds protein analyzer. We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to quantify the ability of plasma Aβ seeding activity to distinguish between AD and NADD or NC individuals. Spearman’s correlation was used to examine the associations between plasma Aβ seeding activity and global cognitive function or conventional AD biomarkers.

Results

The Aβ seeding activities were 0.83 (0.58–1.16) A.U. in AD, 0.42 (0.04–0.74) A.U. in NADD and 0.42 (0.09–0.69) A.U. in NC, respectively. The Aβ seeding activity was able to identify AD patients and distinguish them from NC or NADD with high accuracy (AUC = 0.85–0.86). In addition, the plasma Aβ seeding activity showed a strong correlation with cognitive performance (mini-mental state examination, r = − 0.188; Montreal cognitive assessment, r = − 0.189; clinical dementia rating, r = 0.205) and conventional biomarkers (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] Aβ42/40, r = -0.227; CSF T-tau/Aβ42, r = 0.239; CSF P-tau/Aβ42, r = 0.259).

Conclusion

Our results confirmed that plasma Aβ seeding activity is an antibody-free and low-cost biomarker for the diagnosis of AD.

Trial registration

Trial registration number NCT04850053

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of studies investigating the development of biomarkers for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has increased throughout medical communities worldwide [1]. Among the novel approaches employed are those exploiting the polymerization property of β-amyloid (Aβ), that is, the ability to act as seeds that can recruit other soluble monomers and assemble to form aggregates [2]. Aβ seeds, including small, soluble aggregates, and large, insoluble fibrils, are the major toxic substances associated with the pathology of AD [3, 4]. Extensive evidence suggests that soluble Aβ seeds circulate in biological fluids such as the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [5] and blood [6, 7]. Thus, Aβ seeds have become a promising candidate biomarker for the specific biochemical diagnosis of AD. In this context, one important objective in current research is to detect and quantify small amounts of Aβ seeds present in the biological fluids of AD patients for clinical applications.

Efforts to measure Aβ seeds in humoral fluids are currently underway. Recently, a novel assay has been developed to detect minute amounts of Aβ seeds in the CSF using protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) technology with high sensitivity and specificity [5]. However, because of the invasive nature of lumbar puncture of CSF collection, this method is not practical to collect the CSF for routine early detection of Aβ seeds during clinical visits or for serial evaluation during clinical trials. Given that blood sampling is relatively easier and much less invasive, blood Aβ seeds may serve as a more practical diagnostic biomarker for AD. Thus, a clinically applicable method to measure Aβ seeding activity in the blood is required to properly diagnose and monitor AD. In this context, we have developed an AD-seeds protein analyzer, in which a fluorescence microplate reader was combined with an oscillating mixer or water-bath-type ultrasonicator. In AD-seeds protein analyzer, seeding activities in the blood samples from patients can be amplified by several orders of magnitude in vitro using either sonication or shaking to accelerate polymerization. If the same amount of monomeric Aβ were spiked into AD and non-AD plasma samples, a different kinetic pattern of aggregation would be observed between the two groups. The AD-seeds protein analyzer measures Aβ seeds in the blood, unlike conventional techniques, such as single-molecule array (Simoa) technology [8] or mass spectrometry-based assays [9], which directly measure Aβ molecules. In the case of analytic techniques based on the immunoassay platform, the requirement of expensive equipment limits their widespread application. In contrast, our AD-seeds protein analyzer is an antibody-free and cost-effective approach for measuring blood biomarkers.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the analytic performance of AD-seeds protein analyzer to measure Aβ seeding activity in the plasma of AD patients and show its performance in the differential diagnosis of the disease. We distinguished AD patients from non-AD individuals by measuring the Aβ seeding activity in plasma samples after spiking synthetic Aβ. Our hypothesis was that the plasma Aβ seeding activity from AD patients would be different from that in non-AD subjects.

Materials and methods

Biological samples

In the present study, we used plasma samples from 79 patients with the diagnosis of probable AD as defined by the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines [10]. The non-AD individuals included 75 subjects with cognitively normal (NC) and 64 with non-AD dementia (NADD) (i.e., vascular dementia [VaD], frontotemporal dementia [FTD], dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB], and other dementia types). Table 1 displays a summary of the demographic characteristics of these subjects. Subjects were recruited consecutively from the inpatient and outpatient departments of the Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University between January 2018 and December 2020. All subjects underwent neuropsychological assessments including the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) for global cognitive functions, and clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale for clinical disease severity. Most (94.5%) participants were assessed using apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping. Conventional biomarkers of AD (Aβ42, P-tau, and T-Tau) were analyzed if the CSF samples were available. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from every participant. The investigators were blinded to sample source information during the experiments and analysis.

Processing of plasma samples

Plasma samples were processed to remove albumin that interfered with the Aβ aggregation [11, 12] (Fig. 1). Briefly, 20 μL of a sample was mixed with 1 volume of albumin depletion reagent (Invent, USA) by pipetting the solution up and down for 10–20 times. Thereafter, samples were centrifuged at 14,000g for 2–3 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 150 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

Schematic representation of steps during processing of plasma samples and the AD-seeds protein analyzer. To remove albumin, samples of plasma were incubated with 1 volume of albumin depletion reagent. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended directly in PBS, and then mixed with 5 μM Aβ40 and 20 μM ThT. Samples were subjected to a round of 130 cycles. The kinetics of fibril formation was monitored real time by the reading of the fluorescence intensity every 30 min using 440±10 nm excitation and 480±10 nm emission wavelengths. Aβ, β-amyloid; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PBS, phosphate buffered saline

Plasma Aβ seeding activity measurements

AD-seeds protein analyzer is based on the seeding-nucleation mechanism to cyclically amplify the process of protein misfolding and aggregation, enabling efficient amplification of small quantities of Aβ seeds [6]. Therefore, we can detect the presence of Aβ seeds in peripheral blood by measuring the seeding activity in a plasma sample over a monomeric Aβ substrate. Briefly, samples of seed-free, monomeric Aβ40 (Abcam, UK) at a concentration of 5 μM in PBS buffer, pH 7.4 were placed in opaque 96-well plates in the presence of 20 μM Thioflavin-T (ThT) at a final volume of 200 μL. For each test, we added 20 μL of plasma samples from patients and control subjects. Each sample was run in triplicate. Samples were subjected to cyclic agitation (1 min at 500 rpm followed by 29 min without shaking) at 37 °C. The increase of ThT fluorescence was monitored every 30 min (440 ± 10 nm excitation, 480 ± 10 nm emission).

Determination of the kinetic parameter

The differences in the Aβ seeding activity between different samples were evaluated via P42 (We have selected the fluorescence amplitude ratio throughout all cycles for analysis. Because P42 is the best point to distinguish the AD, NADD and NC, we determine it as a threshold.) estimation. P42 corresponds to the extent of aggregation (measured as ThT fluorescence) at 42 h. Importantly, we divided the ThT fluorescence in plasma samples by that in blank samples to calculate a standard ratio, so as to minimize intra-individual variations.

CSF analysis

CSF samples were collected in 10 mL polypropylene tubes and transported to the laboratory within 2 h. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 2000g at 4°C. All but the bottom 500 μL was aliquoted (500 μL) into 1.5ml polypropylene tubes and immediately stored at – 80 °C until analysis. CSF T-tau, P-tau, Aβ42, and Aβ40 peptide concentrations were measured by the human Luminex 4-plex xMAP assay (Millipore; US) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CSF analyses were performed blinded to the clinical diagnoses.

Statistical analysis

Group-wise comparisons of demographic, clinical, and biomarker characteristics were assessed using Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous and chi-squared test for categorical variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and binary logistic regression (with age, sex, education, and APOE ε4 status as covariates) were applied to analyze the diagnostic value of plasma Aβ seeding activity in differentiating AD samples from NC or NADD. In individuals who had cognitive test scores and CSF assessments, Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to examine the associations between plasma Aβ seeding activity and global cognitive function or conventional AD biomarkers. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 7.0 and the IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in the article. Any additional information required are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the included participants

The between-group difference in age was not significant. However, there were significant differences in sex, education, and disease duration among groups. The number of APOE ε4 carriers (homozygote or heterozygote) was higher in the AD patients (55.1%) than in the NC (18.7%) or NADD individuals (19.4%). As expected, the AD and NADD patients exhibited lower performance on the global cognitive function test than the control group did. Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of the research participants are summarized in Table 1.

Detection of Aβ seeding activity in the plasma of AD patients

Figure 2A shows the average kinetics of aggregation in six representative samples from the AD patients, NC, and NADD patients. The result indicates that plasma from AD patients significantly accelerates Aβ aggregation as compared to those from NC and NADD patients (p < 0.001).

Results of AD, NC, and NADD patients. Representative aggregation curves of seed-free Aβ40 in the presence of plasma samples from AD patients, NC individuals, and NADD patients (A). The values represent the average and SE of six different patients, representative of the average results in each group. The extent of amyloid formation obtained after 84 cycles, i.e., 42 h of incubation (P42), is measured in each patient (B). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; A.U., arbitrary units; NADD, non-AD dementia; NC, cognitively normal. ***p<0.001

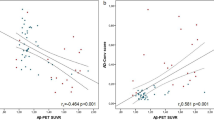

Detection of Aβ seeding activity toward an accurate diagnosis of AD

To determine the effect of individual samples on Aβ aggregation, we estimated the P42, defined as the extent of Aβ aggregation at 42 h (Fig. 2B). By comparing the P42 parameter among the groups, a highly significant difference was observed between AD (0.83 [0.58–1.16] A.U.]) and non-AD samples from NC individuals (0.42 [0.09–0.69] A.U.]), or NADD patients (0.42 [0.04–0.74] A.U.). Using the P42 values, we calculated the diagnostic performance of the plasma Aβ seeding activity. To determine the performance of the test, we carried out a detailed statistical analysis using a ROC analysis (Fig. 3). We estimated an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.86 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.80–0.92) in relation to the age-matched NC, whereas 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.92) to differentiate for AD patients from NADD patients. If confirmed with a larger number of patients, the ability of Aβ seeding activity to distinguish AD from non-AD individuals can have important clinical application.

ROC curve analysis of sensitivity and specificity of the composite score of combing Aβ seeding activity and APOE ε4 status. To evaluate the performance of the composite score to distinguish AD patients from non-AD individuals, we plotted the true positive rate (sensitivity) in function of the false positive rate (specificity) for different cut-off points. The performance of the test, estimated as the area under the curve was 0.86 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.80–0.92; sensitivity: 81.2%, specificity: 80.0%, positive predictive value: 78.9%, negative predictive value:82.2%) and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.92; sensitivity: 81.2%, specificity: 75.8%, positive predictive value: 78.9%, negative predictive value:78.3%) when AD compared with NC or NADD, respectively. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ, β-amyloid; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; NADD, non-AD dementia; NC, cognitively normal

Correlation of plasma Aβ seeding activity and global cognitive function or conventional AD biomarkers

All participants underwent clinical evaluations using global cognitive function tests. Thus, no samples were excluded from this analysis. The plasma Aβ seeding activity values were strongly correlated with the scores on the MMSE (r = − 0.188, p = 0.005), MoCA (r = − 0.189, p = 0.005), and CDR (r = 0.205, p = 0.002) in the whole group (Table 2).

Subjects without CSF data were excluded from the correlation analysis between plasma Aβ seeding activity and conventional AD biomarkers. Thus, 110 subjects (AD, n = 56; NADD, n = 64) were included in the correlation analyses. The plasma Aβ seeding activity values were strongly correlated with CSF Aβ42/40 (r = − 0.227, p = 0.013), CSF T-tau/Aβ42 (r = 0.239, p = 0.008), and CSF P-tau/Aβ42 (r = 0.259, p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, Aβ seeding activities in plasma of AD and non-AD individuals were measured using the novel AD-seeds protein analyzer. We demonstrated that the plasma Aβ seeding activity had a robust performance in distinguishing AD patients from non-AD individuals. The current observations supported the notion that plasma Aβ seeding activity could serve as a potential blood-based biomarker for the sensitive diagnosis of AD.

Previous studies have shown that injecting AD brain extracts in the brains in mouse models of AD could accelerate amyloid deposition through prion-like mechanisms [13,14,15,16]. Recently, several reports have shown that infusion of blood from mice displaying cerebral amyloidosis accelerated amyloid pathology in animal models of AD, supporting the concept that Aβ seeds are present in the blood and are implicated in the development of AD [17]. Another report has showed that wild-type mice could develop brain amyloidosis after parabiosis in APP/PSEN1 transgenic mice, further supporting the important role of circulating Aβ on brain pathology [18]. In this study, we developed a new instrument to measure Aβ seeding capability in the plasma of AD patients. We found that plasma Aβ seeding activity demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in detecting AD in the dementia stage of the disease, which makes plasma Aβ seeding activity a potential candidate for an AD-specific blood biomarker. More importantly, plasma Aβ seeding activity showed high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing between AD and NADD patients. The capability of plasma Aβ seeding activity to distinguish AD patients from NADD patients might be valuable in clinical practice and trials. Note that the differential diagnosis of AD among other dementias is difficult using clinical testing [19]. Plasma Aβ seeding activity may be used to improve the accuracy of differential diagnosis of dementia patients. Together, our findings provide the proof-of-principle basis for the detection of blood-based Aβ seeds for AD diagnosis.

Owing to its low concentrations in the blood, detecting crude Aβ seeds in plasma has been a challenge, especially in the presence of several interfering factors, such as albumin and immunoglobulin, at high concentrations [20, 21]. Given that albumin is the most abundant plasma protein reported to bind Aβ impeding its aggregation [11, 12], we determined the sensitivity of our assay in the absence of albumin. Even at ultralow concentrations, the formation of Aβ aggregates in the blood of AD patients may be initiated via incubation with spiked synthetic Aβ peptides [21]. In previous studies, researchers were able to differentiate Aβ oligomerization tendency by spiking Aβ42 into the plasma of AD patients and control individuals [20,21,22,23,24]. The Aβ oligomerization differences in plasma have significant potential in AD diagnosis. In our study, Aβ seeding activity levels in the plasma were increased in the AD patients, in agreement with previous reports mentioned before.

It is also necessary to identify markers that correlate with the severity of dementia in AD patients. In this study, the correlation coefficient indicated a moderately strong relationship between the elevated plasma Aβ seeding activity and the decreased general cognitive level. Previous studies have demonstrated that the plasma Aβ oligomerization tendency was correlated with the general cognitive function and episodic memory [23]. Similarly, measuring the plasma Aβ seeding activity using our instrument could be associated with symptom severity, which requires further investigation for its potential use in monitoring disease progression or as a prognostic biomarker of AD. Furthermore, our findings show a positive correlation between plasma Aβ seeding activity and the established CSF biomarkers, suggesting that our instrument may offer a good opportunity for a much-needed sensitive biochemical diagnosis of AD. This is consistent with previous studies that found the levels of Aβ oligomerization in the plasma were correlated strongly with CSF core biomarkers [20]. Moreover, studies conducted in animal models showed that decreasing Aβ seeding activity in plasma was significantly correlated with the reduction of brain Aβ deposits [6]. Overall, these findings indicate that plasma Aβ seeding activity mirror AD pathology and have clinical potential for AD diagnosis.

Limitations

Although the present study revealed the interesting potential of plasma Aβ seeding activity to serve as a blood-based biomarker, our findings have limitations and should be interpreted with caution. For instance, compared with AD and NC, the number of cases with NADD, such as VaD, FTD, and DLB, is relatively small. Our findings need to be further validated with a larger cohort and in longitudinal studies. In addition, individuals with preclinical AD could not be included. Further studies are needed to determine if plasma Aβ seeding activity can be detected in blood preclinically in AD. Another limitation of our study is that the characteristics of samples used in the analysis were mainly based on the clinical diagnosis. Thus, a follow-up or pathologically confirmed diagnosis of each case will be critical to validate the differential diagnostic utility of the plasma Aβ seeding activity. It is possible that the diagnostic accuracy of the test could be even higher if neuropathologically confirmed samples were used.

Conclusions

Plasma samples of AD and non-AD subjects were differentiated using the AD-seeds protein analyzer, which measured the Aβ seeding activity in the plasma. Furthermore, plasma Aβ seeding activity was found to have a robust performance in the differential diagnosis of AD from non-AD individuals. Based on the current findings, measuring the Aβ seeding activity in plasma could be a simple and reliable blood-based diagnostic biomarker for AD. However, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying plasma Aβ seeding activity. Longitudinal studies undertaken during the predementia stage of AD should also be conducted to assess clinical applications of this biomarker for early detection and monitoring of this disease.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ:

-

β-amyloid

- NADD:

-

Non-AD dementia

- NC:

-

Cognitively normal

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- PMCA:

-

Protein misfolding cyclic amplification

- VaD:

-

Vascular dementia

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA:

-

Montreal cognitive assessment

- CDR:

-

Clinical dementia rating

- APOE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- ThT:

-

Thioflavin-T

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

References

Molinuevo JL, Ayton S, Batrla R, Bednar MM, Bittner T, Cummings J, et al. Current state of Alzheimer's fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(6):821–53.

Cazzaniga FA, De Luca CMG, Bistaffa E, Consonni A, Legname G, Giaccone G, et al. Cell-free amplification of prions: Where do we stand? Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2020;175:325–58.

Jucker M, Walker LC. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501(7465):45–51.

Morales R, Callegari K, Soto C. Prion-like features of misfolded Abeta and tau aggregates. Virus Res. 2015;207:106–12.

Salvadores N, Shahnawaz M, Scarpini E, Tagliavini F, Soto C. Detection of misfolded Abeta oligomers for sensitive biochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Rep. 2014;7(1):261–8.

Estrada LD, Chamorro D, Yanez MJ, Gonzalez M, Leal N, von Bernhardi R, et al. Reduction of Blood Amyloid-beta Oligomers in Alzheimer's Disease Transgenic Mice by c-Abl Kinase Inhibition. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(3):1193–205.

Carlomagno Y, Manne S, DeTure M, Prudencio M, Zhang YJ, Hanna Al-Shaikh R, et al. The AD tau core spontaneously self-assembles and recruits full-length tau to filaments. Cell Rep. 2021;34(11):108843.

Simren J, Leuzy A, Karikari TK, Hye A, Benedet AL, Lantero-Rodriguez J, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(7):1145–56.

Nakamura A, Kaneko N, Villemagne VL, Kato T, Doecke J, Dore V, et al. High performance plasma amyloid-beta biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2018;554(7691):249–54.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9.

Milojevic J, Esposito V, Das R, Melacini G. Understanding the molecular basis for the inhibition of the Alzheimer's Abeta-peptide oligomerization by human serum albumin using saturation transfer difference and off-resonance relaxation NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(14):4282–90.

Milojevic J, Melacini G. Stoichiometry and affinity of the human serum albumin-Alzheimer's Abeta peptide interactions. Biophys J. 2011;100(1):183–92.

Hamaguchi T, Eisele YS, Varvel NH, Lamb BT, Walker LC, Jucker M. The presence of Abeta seeds, and not age per se, is critical to the initiation of Abeta deposition in the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):31–7.

Morales R, Duran-Aniotz C, Castilla J, Estrada LD, Soto C. De novo induction of amyloid-beta deposition in vivo. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1347–53.

Stohr J, Watts JC, Mensinger ZL, Oehler A, Grillo SK, DeArmond SJ, et al. Purified and synthetic Alzheimer's amyloid beta (Abeta) prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(27):11025–30.

Eisele YS, Obermuller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330(6006):980–2.

Morales R, Duran-Aniotz C, Bravo-Alegria J, Estrada LD, Shahnawaz M, Hu PP, et al. Infusion of blood from mice displaying cerebral amyloidosis accelerates amyloid pathology in animal models of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):213.

Bu XL, Xiang Y, Jin WS, Wang J, Shen LL, Huang ZL, et al. Blood-derived amyloid-beta protein induces Alzheimer's disease pathologies. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(9):1948–56.

Karantzoulis S, Galvin JE. Distinguishing Alzheimer's disease from other major forms of dementia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(11):1579–91.

Wang MJ, Yi S, Han JY, Park SY, Jang JW, Chun IK, et al. Oligomeric forms of amyloid-beta protein in plasma as a potential blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):98.

Choi Y, Joh Y, Ryu JS, Kim K, Seo D, Kim S. Endogenous Abeta peptide promote Abeta oligomerization tendency of spiked synthetic Abeta in Alzheimer's disease plasma. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2021;111:103588.

An SSA, Lee BS, Yu JS, Lim K, Kim GJ, Lee R, et al. Dynamic changes of oligomeric amyloid beta levels in plasma induced by spiked synthetic Abeta42. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):86.

Meng X, Li T, Wang X, Lv X, Sun Z, Zhang J, et al. Association between increased levels of amyloid-beta oligomers in plasma and episodic memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):89.

Youn YC, Lee BS, Kim GJ, Ryu JS, Lim K, Lee R, et al. Blood Amyloid-beta Oligomerization as a Biomarker of Alzheimer's Disease: A Blinded Validation Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(2):493–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all neuropsychological assessors and patients for their cooperation.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Scientific Instrument and Equipment Development Project (31627803); the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81530036); the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20354); Beijing Scholars Program; Beijing Brain Initiative from Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z201100005520016, Z201100005520017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jianping Jia: study concept and design, drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Tingting Li: study concept and design, drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Jianwei Yang: study concept and design, drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Baian Chen: study concept and design. Wei Qin: drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Cuibai Wei: study concept and design. Yang Song: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Qigeng Wang: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Yan Li: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Longfei Jia: study concept and design, drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Jianping Jia, Tingting Li, and Jianwei Yang contributed equally to this paper. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved and monitored by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital. Signed informed consent was provided by all the patients and control subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors report no disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, J., Li, T., Yang, J. et al. Detection of plasma Aβ seeding activity by a newly developed analyzer for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res Therapy 14, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-00964-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-00964-2