Abstract

Objective

Few patients achieve full control of their coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors. Follow-up, such as cardiac rehabilitation, is important to increase adherence to lifestyle changes and treatment, to improve the patient’s risk profile, and to treat established complications of CAD clinical events. However, the type of follow-up patients receive varies. Therefore, the aim of this research note was to describe and compare patients’ self-reported use of health services, the type of follow-up patients reported to prefer, and the type of information patients reported to be important, in two countries with different follow-up practices after PCI.

Results

We included 3417 patients in Norway and Denmark, countries with different follow-up strategies after PCI. The results showed large differences between the countries regarding health services used. In Denmark the most frequently used health services were consultations at outpatient clinics followed by visits to the general practitioner and visits to the fitness centre, whereas in Norway visits to the general practitioner were most common, followed by rehospitalisation and no follow-up used. However, patients found the same type of follow-up and information important in both countries. Patients’ perceived need for follow-up and information decreased over time, suggesting a need for early follow-up when the patients are motivated.

Trial registration: NCT03810612 (18/01/2019).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines [1, 2] recommend initiating secondary preventive strategies, as well as enabling patients to self-manage their own lifestyle. Secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation (CR) for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) consist of an extensive set of treatment options ranging from optimal medical therapy, lifestyle interventions and stress management [1, 3]. Despite proven benefits on both morbidity and mortality [4, 5], few patients achieve complete risk factor control [6]. The quality of the secondary prevention offered to patients varies between and within countries [7,8,9]. Furthermore, CR participation rates are reported to be less than 50% [10,11,12]. Geographical accessibility and lack of continuity in the healthcare system have been identified as barriers to participation [13]. In Denmark, patients are routinely referred to secondary prevention and CR [14], while Norway does not practice routine referral to any kind of follow-up. For many patients, the general practitioner (GP) is therefore a key person to initiate and coordinate secondary prevention strategies and provide long-term follow-up.

Understanding patients’ own preferences as regards the provision of secondary prevention and CR after PCI can potentially increase adherence to treatment and lifestyle changes [15, 16]. Therefore, the aim of this research note was to describe and compare patients’ self-reported use of health services, the type of follow-up patients reported to prefer, and the type of information patients reported to be important, in two countries with different follow-up practices after PCI.

Main text

Methods

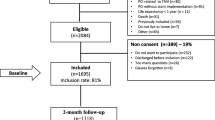

Real-world data from 3417 patients at three Norwegian and four Danish referral PCI centres were collected in the prospective multicentre CONCARDPCI cohort study between June 2017 and May 2020 [17]. Patients were eligible to participate if they gave informed consent, were undergoing PCI with stent implantation according to diagnostic criteria set out in ESC guidelines [18], were ≥ 18 years of age, and living at home at the time of inclusion. Those who did not speak Norwegian/Danish or were unable to complete the questionnaires due to reduced capacity, or who were institutionalised, had a life expectancy of less than one year, or had undergone PCI without stent implantation, in connection with transcatheter aortic valve implantation or MitraClip examination, or who had previously been enrolled in CONCARDPCI (readmissions) were excluded (see Additional file 1). Comparison of participants and those declining participation in the study for the Norwegian centres is available in Additional file 2.

De-novo-created questions were developed by the CONCARDPCI investigators to assess patients’ use of health services, the type of follow-up patients prefer, and information patients find important at 2-, 6- and 12-month follow-up. Development of the questions were based on in-depth interviews performed prior to this study. The three de novo-questions reported here were: (1) During the last two months, which of the following health services have you used? (Multiple answers possible from predefined answers ranging from general practitioner to alternative treatment, including none of the above). (2) Looking back at the last two months, which type of follow-up would you have preferred? (Multiple answers possible from predefined answers ranging from cardiac rehabilitation daytime 3–5 weeks, to internet-based follow-up, including do not want follow-up). (3) Looking back at the last two months, what type of information is important in the follow-up? (Multiple answers possible from predefined answers ranging from information about heart medication to sexuality, including do not need information). At 6- and 12-month follow-up the questions were phrased in the last six months.

Results

Patients were predominantly male (78%), with a mean age of 66 years (SD 11, range 20–96 years), and cohabitating (76%). Most patients had a lower educational level (20% primary school and 43% vocational school). Acute coronary syndrome was the most frequent cause of admission for PCI (62%), and 26% had previously undergone PCI. Patient characteristics are presented in Additional file 3.

Figure 1 shows the type of health services patients reported to have used after PCI, (see Additional file 4 for Health services used in a table version). In Norway, more than 80% reported visiting their GP at 2-month follow-up, compared to 40% in Denmark. Moreover, consultations at an outpatient clinic were more common in Denmark compared to Norway at 2-month follow-up (46% vs. 10%). Following GP and rehospitalisation (13%), not having had any follow-up (13%) was most reported by the Norwegian patients. For the Danish patients, consultations at an outpatient clinic were followed by visits to the GP (40%) and going to the fitness centre (34%) as the most used services. The proportion of patients not participating in any follow-up care was higher in Denmark (18%) than Norway (13%). The rehospitalisation rate for Danish patients (14%) was similar to the Norwegian patients (13%). For the Norwegian patients, 10% had attended an outpatient clinic and 12% a fitness centre. In Denmark, the same top 3 health services were used at 12-month follow-up, although the order was different. In Norway, the GP was most used (92%), specialist outside hospital second (19%) and rehospitalised third (19%).

At 12-month follow-up, 11% of Danish patients and 6% of Norwegian patients reported not having used any health services.

Figure 2 shows the type of follow-up patients reported that they preferred (see Additional file 5 for Preferred follow-up in a table version). The most preferred follow-up was physical activity led by a physiotherapist at 2-, 6- and 12-month follow-up in both countries. At 2-month follow-up, outpatient consultation, tailored information, CR (daytime) for 3–5 weeks and day courses were the most preferred follow-up. At 12 months, do not want follow-up was among the five most reported responses for both Norwegian and Danish patients. At 2-month follow-up, 14% did not want follow-up, which increased to 20% at 12-month follow-up.

Figure 3 shows the themes patients considered important in follow-up, which were similar between the Norwegian and Danish patients at all measuring time points (see Additional file 6 for Important themes in follow-up in a table version). The top five themes in both countries at all measuring timepoints were heart medications, physical activity, diet, general information about CAD, and what to do if they experienced a new cardiac event.

From the index hospitalisation to 12-month follow-up, a lower proportion of patients reported that physical activity, diet and general information about CAD were important themes. Additionally, an increasing proportion reported that they do not need information over time.

Discussion

To our knowledge, few studies have investigated patients’ perceived need for follow-up and information after PCI. We found large differences in the type of health services patients had used in two countries with similar healthcare systems and reimbursement policies but with different follow-up practices after PCI. Norwegian patients to a larger extent visit their GP, while outpatient clinics are more commonly used in Denmark. Despite a more systematic referral of patients to CR, more patients in Denmark reported that they did not receive any follow-up. Although there are differences in the type of health services used, patients in Norway and Denmark preferred the same type of follow-up and valued the same type of information at 2-, 6- and 12-month follow-up, as shown in Fig. 4.

Patients’ hospital stay after PCI is short and they usually experience immediate relief from their symptoms. Thus, patients often think that they have been ‘fixed’[19]. The need for lifestyle changes may therefore not be that apparent. Several barriers to risk factor control and lifestyle changes have been identified, including psychosocial, clinical and accessibility issues [20, 21]. Healthcare providers’ beliefs about the benefit of CR might influence the information patients receive about CR and whether they are referred to CR or not [22, 23].

In some countries, including Norway, patients do not routinely participate in hospital-based CR or any other follow-up after PCI. Instead, they must contact their GP themselves. Lack of information flow between hospitals and patients, and hospitals and GPs impedes continuity of care [24]. This lack of systematically providing CR contributes to the notion that the patients’ condition is not that serious. In addition, during the waiting time for CR or other follow-up, patients’ motivation for lifestyle changes might have changed and they may already have slipped back into previous habits. Some patients might think that CR only corresponds to physical activity [25], making them reluctant to participate.

Our results show that physical activity led by a physiotherapist was the most preferred follow-up at all measuring time points in both countries. Physical activity is an important part of secondary prevention and CR strategies [2]. However, it should also be continued after structured follow-up has been completed.

Being aware of patients’ health literacy is also important when informing them about their chronic disease, as well as tailoring the information to the patient and their specific situation [26]. Through secondary prevention and CR, patients gain more knowledge about their condition, the importance of adhering to treatment and how to incorporate lifestyle changes. Tailoring the follow-up to older adults, females or those living far from a CR centre might increase referral, uptake and adherence. To ensure that patients are able to access, understand, appraise, remember and use the knowledge, they need to make informed choices regarding their own situation [27]. Thus, individualisation and longer-term follow-up than currently is provided, might be needed. The high proportion of patients who preferred follow-up on physical activity, diet and medications 12 months after PCI suggests that patients know that it is important but find it hard to adhere.

Conclusion

There were large differences in the health services used in two countries with similar healthcare systems and reimbursement policies, but with different follow-up strategies after PCI. Patients in both countries found the same type of follow-up and information important. However, the perceived need for follow-up and information decreased over time.

This suggests a need to provide early structured follow-up when patients are still motivated. New modes of delivery and individual tailoring of secondary prevention strategies and CR are needed to overcome barriers to adherence. Primary and specialist healthcare providers should collaborate closely to implement secondary prevention strategies and CR after PCI and apply a long-term perspective to ensure that patients are able to self-manage their CAD risk profile and adhere to recommended treatment.

Limitations

CONCARDPCI is a large multicentre cohort study with broad inclusion criteria and 80% inclusion rate, as well as low attrition. However, the study is not without limitation. The retrospective nature of patients’ self-report might underreport use of health services. This study presents patients self-reported use of a range of health services, preferred health services and information important to them in follow-up care. However, these variables are presented descriptively without examining associations with sex, age or educational level, which is known to influence e.g., participation rates in CR. The study was conducted in two Nordic countries, which may limit its generalisability to countries without universal health coverage.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity to protect study participant privacy. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Haukeland University Hospital.

References

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106.

Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3227–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484.

Frederix I, Dendale P, Schmid J-P. Who needs secondary prevention? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317706112.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e563–95. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000677.

Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ. 2015;351:h5000. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5000.

De Bacquer D, Astin F, Kotseva K, et al. Poor adherence to lifestyle recommendations in patients with coronary heart disease: results from the EUROASPIRE surveys. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29:383–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwab115.

Colella TJ, Gravely S, Marzolini S, et al. Sex bias in referral of women to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation? A meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:423–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314520783.

Abreu A, Pesah E, Supervia M, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation availability and delivery in Europe: How does it differ by region and compare with other high-income countries? Endorsed by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:1131–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319827453.

Abreu A, Frederix I, Dendale P, et al. Standardization and quality improvement of secondary prevention through cardiovascular rehabilitation programmes in Europe: The avenue towards EAPC accreditation programme: a position statement of the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320924912.

Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D, Investigators E. Determinants of participation and risk factor control according to attendance in cardiac rehabilitation programmes in coronary patients in Europe: EUROASPIRE IV survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:1242–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318781359.

Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, et al. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:824–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318825350.

Benzer W, Rauch B, Schmid JP, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in twelve European countries results of the European cardiac rehabilitation registry. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.059.

Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E, et al. Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:436–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.120.

The Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline on cardiac rehabilitation June 2016. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2015/~/media/E21E277725B8408698A96502F4BEF472.ashx.

Whitty JA, Stewart S, Carrington MJ, et al. Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for a home or clinic based program of chronic heart failure management: findings from the Which? trial. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058347.

Boyde M, Rankin J, Whitty JA, et al. Patient preferences for the delivery of cardiac rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:2162–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.07.010.

Norekvål T, Allore H, Bendz B, et al. Rethinking rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention: a protocol of a multicentre cohort study on continuity of care, health literacy, adherence and costs at all care levels (the CONCARDPCI). In BMJ Open. 2020;10:e031995. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031995.

Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394.

Astin F. Do patients take angioplasty seriously? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17:194–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515117737767.

Resurrección DM, Moreno-Peral P, Gómez-Herranz M, et al. Factors associated with non-participation in and dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programmes: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515118783157.

De Smedt D, De Bacquer D, De Sutter J, et al. The gender gap in risk factor control: Effects of age and education on the control of cardiovascular risk factors in male and female coronary patients. The EUROASPIRE IV study by the European Society of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol. 2016;209:284–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.015.

Gallagher R, Neubeck L, Du H, et al. Facilitating or getting in the way? The effect of clinicians’ knowledge, values and beliefs on referral and participation. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:1141–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316630085.

Elsakr C, Bulger DA, Roman S, Kirolos I, Khouzam RN. Barriers physicians face when referring patients to cardiac rehabilitation: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:414. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.07.61.

Valaker I, Fridlund B, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Continuity of care and its associations with self-reported health, clinical characteristics and follow-up services after percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4908-1.

White S, Bissell P, Anderson C. Patients’ perspectives on cardiac rehabilitation, lifestyle change and taking medicines: implications for service development. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009103.

Beauchamp A, Sheppard R, Wise F, Jackson A. Health literacy of patients attending cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2020;40:249–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000473.

WHO. Health literacy development for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: 2022. ISBN: 978-92-4-005539-1

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance provided by Marie Hayes in the development of Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4.

CONCARDPCI Investigators

Scientific advisory board: Allore H8, Deaton C9, Hadjistavropoulos H10, Zwisler ADO5

Expert Group of regional, national and international collaborators of CONCARDPCI: Aasen T11, Bendz B12, Bjorvatn C1, Brørs G2, Drange AK13, Fridlund B14, Hjertvikrem N1, Igland S15, Instens I1, Larsen AI16, Nordrehaug JE16, Pettersen TR1, Rotevatn S1, Schjøtt J1, Solheim M15, Stiansen R11, Thompson D17, Valaker I3, Wentzel-Larsen T1

Project administration for the cohort study in CONCARDPCI: Norekvål TM1, Fålun N1, Helmark C4, Valaker I3, Brørs G2, Pettersen TR1, Instenes I1, Hjertvikrem N1, Rotevatn S1, Rykkje K1, Ramstad KJ1, Jakobsen T1, Hayes MTN1, Larsen AI16, Espedal M16, Bjørheim PE16, Johnson UEK16, Bendz B12, Dahlviken R12, Grønsund T12, Torbjørnsen LM12, Leifson M12, Rasmussen TB18, Kristensen SA18, Herning M18, Vinther AK18, Jacobsen KB18, Palm P19, Christensen SW19, Kongshavn HM19, Helmark C4, Morsing TS4, Hansen UW4, Hansen MB4, Schønemann HB4, Borregaard B20, Trangbæk A20

8Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, United States of America; 9University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 10University of Regina, Regina, Canada; 11The Norwegian Heart and Lung Patient Organisation, Bergen, Norway; 12Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway; 13Askøy Municipality, Askøy, Norway; 14Centre of Interprofessional Collaboration within Emergence care (CISE), Linnæus University, Växjö, Sweden; 15Førde Hospital Trust, Førde, Norway; 16Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; 17Queens University, Belfast, United Kingdom; 18Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital, Gentofte, Denmark; 19Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; 20Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen. This work was supported by a major grant from the Western Norway Health Authority (912184) to CONCARDPCI. NH is funded through a postdoctoral fellowship from the Norwegian Nurses Association. TRP is funded through a postdoctoral fellowship from the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (no 4800007800). The funders had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

NH did the descriptive statistics on the patient reported questions and wrote the first draft of the paper. NH, GB, II, TRP and TMN all discussed the results, prepared the figures, and contributed to the discussion. CH, SR and ADOZ provided critical comments to manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft. CONCARDPCI Investigators conducted the CONCARDPCI study, with data collection in Denmark and Norway.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical Research in Western Norway (REK 2015/57) and the Data Protection Agency in the Zealand region for the Danish centres (REG-145-2017). All participants provided written informed consent and patients were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any explanation. The study conformed with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. CONCARDPCI is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03810612 18/01/2019).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Flowchart CONCARDPCI data collection.

Additional file 2

. Comparison of participants and those declining participation in the study for the Norwegian centres.

Additional file 3

. Patient characteristics.

Additional file 4

. Patient reported use of health services after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Additional file 5

. Type of follow-up patients reported that they prefer after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Additional file 6

. Themes patients reported to be important in follow-up after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hjertvikrem, N., Brørs, G., Instenes, I. et al. Use of health services and perceived need for information and follow-up after percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Res Notes 17, 20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06662-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06662-y