Abstract

Background

Post-partum depression is a common complication of women after childbirth. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of and factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers attending a child immunization clinic at a maternity hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted among 346 post-partum mothers at six to ten weeks after delivery using systematic random sampling. Mothers were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to screen for depressive symptoms. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the association of post-partum depressive symptoms with socio-demographic and maternal factors.

Results

The prevalence of post-partum depressive symptoms among mothers was 30%. Mothers aged 20 to 29 years were less likely to have depressive symptoms (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.21-0.76) compared to older mothers. Similarly, mothers with a history of pregnancy-induced health problems were more likely to have depressive symptoms (aOR = 2.16; CI: 1.00-4.66) and subjective feelings of stress (aOR = 3.86; CI: 1.84-4.66) than mothers who did not.

Conclusions

The number of post-partum mothers experiencing depressive symptoms was high; almost one-third of the participants reported having them. Pregnancy-induced health problems and subjective feelings of stress during pregnancy in the post-partum period were found to be associated with depressive symptoms among these women. Screening of depressive symptoms should be included in routine antenatal and postnatal care services for early identification and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Mental health problems are a major public health issue for women of reproductive age (15–44 years) in both high and low-income countries. About 7% of the global burden of diseases among women is contributed to mental health problems, especially among women of reproductive age [1]. The term post-partum depression (PPD) refers to a non-psychotic depressive state that begins in the post-partum period, after the child birth [2-4]. PPD is a mood disorder that can occur at any time during the first year after delivery [1,5]. Approximately 10-15% of women in the childbearing age experience this common complication of PPD [1]. PPD affects the health of not only the mother, but also of her children, especially mother-child bonding and the relationships among family members [6]. At present, PPD is not classified as a separate disease but diagnosed as an affective or mood disorders, according to the in Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) [7,8]. A meta-analysis of 59 studies from North America, Europe, Australia and Japan, found an overall prevalence rate of post-partum depressive symptoms of 13% [4]. A range of prevalence rates of post-partum depressive symptoms among post-partum women has also been found in developing countries, including India and Pakistan from 11 to 40% [9,10].

Earlier studies have found that risk factors for depressive symptoms are clustered into five major groups: biological, including changes in hormone levels and the age of mother; physical, including chronic health problems and antenatal depression; psychological, including prenatal anxiety, stress, lack of social support and stressful life; obstetrics/pediatrics, including unwanted pregnancy, history of loss of pregnancy and severely ill infants; and socio-cultural, including status of mother and poverty [6,11-15]. PPD has been associated with tragic outcomes, such as maternal suicide and infanticide [4]. Economic deprivations, gender of the infant, marital violence, smoking during pregnancy and hunger have also been associated with PPD [9,16].

A study conducted in the Dhanusha district of Nepal reported a number of factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers, such as multiple births, caesarean section deliveries, serious perinatal health problems, illiteracy of the mother, higher parity, poor antenatal care, never having a son, having an illiterate husband, and lower maternal age [17]. Psychological violence during pregnancy by an intimate partner was strongly associated with PPD [18]. Low self-esteem and socio-economic status were significant predictors for depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers [19,20]. The prevalence of PPD symptoms was reported to be between 5.0 and 22.2% in Nepal, in different studies with various time frames [17,21]. The Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Survey (2009) identified suicide as a leading cause of death (16%) among women of reproductive age, with depression being the main cause for this [22]. Women having depressive symptoms during the postnatal period have a higher chance of self-harm than others in later years [23,24]. Also, depressive symptoms during the postnatal period are potential causes for neglect of the child and child abandonment. There are few studies conducted in Nepal on PPD symptoms, including some older studies [17,21,25,26]. However, the focus of those studies was limited to an aboriginal group in Nepal [25], or they had a small sample size [21]. Thus, there is the need for further studies to report the prevalence and associated factors of PPD symptoms in the country. Findings from such studies will be helpful in the design of prenatal and postnatal counseling and support to mothers, with special attention to vulnerable groups. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to: (1) calculate the prevalence of PPD symptoms among mothers; and (2) identify the factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers.

Methods

Study setting

Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital (PMWH) is the largest public hospital for maternity care in Nepal. This hospital receives a number of diverse women in age, ethnicity and educational status [27]. The PMWH runs a child immunization clinic everyday, which provides BCG, DPT, Polio and Measles vaccine to infants. The children attending this immunization clinic are generally accompanied by their mothers. Therefore, using this as the site for recruitment of post-partum mothers. We excluded mothers having chronic health problems, mothers with severely ill children and care takers other than post-partum mothers.

Sample, tools and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional study using a semi-structured questionnaire between August and September of 2012. Mothers who visited the child immunization clinic at a period of six to ten weeks after delivery were included in the sampling frame for this study. Sample size was calculated using the formula N = Z2p q/L2 = 1.962*(0.08)*(0.92)/(0.03)2, taking Z = 1.96, p = 8% = 0.08 (assuming prevalence of PPD = 8%) [17], q = 1– p = (0.92), allowable error (L) = 3%, and level of significance =5%. Assuming a non-response rate of 10%, the sample size was estimated to be 346. A systematic random sampling technique was used to identify the name of mothers from the immunization register.

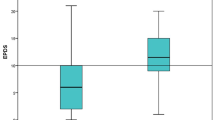

A self-administered version of the EPDS tool was used to screen the depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers. The EPDS tool has been validated and used in different cultural settings, including Nepal [3,21,28-30]. The EPDS tool is a ten-item self-reporting scale that measures the intensity of depressive symptoms experienced within the last 7 days. Each statement is rated on a scale from 0–3 (from “Yes, most of the time”, to “no, not at all”), resulting in a total possible score ranging from 0–30. We added pertinent socio-demographic characteristics and maternal factors to the questionnaire in order to collect information based on literature review [9,21,28]. The Nepali version of a questionnaire was pre-tested in Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital in Kathmandu; the necessary amendments were made to make the questionnaire clearly understandable to mothers. Face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect maternal and socio-demographic information.

Measurement of variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of the interest in this study was the occurrence of PPD symptoms based on EPDS screening criteria. We used an EPDS score ≥10 as a cut-off point to classify the depressive symptoms which has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 84% [31]. An earlier study has stated that the EPDS could convincingly rule out the depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers when a cut-off point of ≥10 was used [32].

Explanatory variables

The explanatory variables investigated were both socio-demographic and maternal factors. Socio-demographic factors included age, ethnicity, occupation, education, and socio-economic status of the family. The Government of Nepal has classified ethnicity into six groups: Dalit, disadvantaged Janajati, disadvantaged non-Dalit Terai caste group, religious minorities, relatively advantaged Janajati and upper caste group [33,34]. In this study, ethnicity was further dichotomized into a relatively disadvantaged ethnic group and a relatively advantaged ethnic group for analysis. Similarly, educational status of parents was categorized as literate and illiterate. Socio-economic status of the family was categorized according to Kuppuswamy’s Scale (KS) [35]. The KS is comprised three variables; namely education, occupation and monthly income of the family head. Scores were given as education from 1 to 7; occupation from 1 to 10 and income from 1 (25 USD) to 12 (500 USD). A total score was further categorized as upper class (KS 26–29), middle class (KS 11–25) and lower class (KS ≤10) [35]. Maternal factors included family size, birth weight of children, type of delivery, pregnancy-induced health problems and subjective feelings of stress recalled during the last six months. Pregnancy-induced health problems included hypertension, headache and pregnancy complications while subjective feelings of stress included loss of interest and feeling, upset or bad during the pregnancy and post-partum period.

Statistical analysis

Data cleaning and coding was done by the first author on the same day as data collection. Data were entered in EpiData version 3.1.1 (The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) and analysis was done using SPSS version 19 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

The descriptive analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics and maternal factors of the study participants were reported as total number and percentages first. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers was reported as percentages. Chi-square analysis was used to test the significance of associations between outcome and explanatory variables. The variables associated in bivariate analyses (p < 0.15) were included in backward stepwise logistic regression analyses.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was received from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Medicine, Maharajgunj Medical Campus, Tribhuwan University, Kathmandu, Nepal. The first author explained the research objectives and took verbal consent from the participants before starting the interview. The participants were ensured that confidentiality of the data will be strictly maintained and told about their right to withdraw from the interview at any time.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Among the 346 respondents interviewed, the mean age was 24.0 (SD 4.7) years and the majority of respondents (72.0%) were 20–29 years of age. More than 90% of mothers were housewives and 83.5% of the respondents were literate. Two in five respondents were from the disadvantaged ethnic group (40.2%). More than 60% of the respondents belonged to middle class families. About one in ten mothers (9.8%) had subjective feelings of stress in the last six months (Table 1).

Prevalence of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers

Out of 346 post-partum mothers, 105 (30.3%) had depressive symptoms (Table 2). Among the sub-groups, about half (47.1%) of mothers ≥30 years of age had depressive symptoms. Likewise, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in mothers whose husbands were illiterate, who had pregnancy-induced health problems and mothers from a lower socio-economic class were 48.0%, 45.2% and 41.7%, respectively. More than half of the respondents (58.8%) who had subjective feelings of stress also had depressive symptoms during post-partum period (Table 3).

Factors associated with post-partum depressive symptoms

The current age of mothers, educational status of mothers and fathers, reasons for reported stress, socio-economic status of families, pregnancy-induced health problems and subjective feelings of stress in the last six months were all found to be associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers in bivariate analyses. However, in the logistic regression analysis, only three variables were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Mothers aged 20–29 years were less likely to report depressive symptoms (aOR = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.21-0.76). Similarly, mothers who had pregnancy induced problems (aOR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.00-4.66) or were suffering from subjective feelings of stress (aOR = 3.86, 95% CI: 1.84-4.66) had a higher likelihood of having depressive symptoms (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study showed that about one-third of mothers had depressive symptoms during post-partum period. Earlier studies reported prevalence of depressive symptoms varies 6 to 12% among women in the post-partum period using an EPDS score cut-off of ≥ 12 [29,30]. A recent cohort study conducted in two hospitals of Nepal, in Dhading and Kathmandu, using an EPDS score ≥13 as a cut-off point, found that 22.2% of post-partum mothers had depressive symptoms [21]. In other developing countries including India and Pakistan, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers have been reported as 11 to 40% [30]. The high prevalence of depressive symptoms reported in this study might be because of lower cut-off point of EPDS score (≥10) compared to previous studies (≥12) [16,29].

The current study found mothers 20–29 years of age were less likely to have depressive symptoms compared to the mothers of the oldest age group. In contrast, earlier studies in Turkey and Canada reported that mothers aged less than 25 years were more likely to report depressive symptoms [36-38]. However, some other studies have found no differences in depressive symptoms by age [39-41]. Women between 20–29 years of age may be more aware of pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, and thus develop confidence to cope with it; in this age group, women in Nepal usually have a parity greater than two [42]. Additionally, this reduces the risk of pregnancy complications further, so these mothers might be at lower risk for depressive symptoms compared to mothers of other ages.

We found that pregnancy-induced health problems and subjective feelings of stress during the last six months were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Stressful situations during pregnancy, such as the pain response to vaginal birth, have been reported to increase the chances of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers [43]. The earlier study conducted in Nepal also showed that stressful life events were associated with depressive symptoms [16]. Depressive symptoms were most common among post-partum mothers who had hyperemesis or premature contractions during pregnancy [44]. Stressful events such as maternity blues on the seventh day after delivery, obsessive preoccupation with cleaning, and judgment that the baby is crying excessively at first were also factors significantly associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers [45]. A review also reported that poor marital adjustment, recent life stressors, and ante-partum depression were strong predictors of PPD symptoms [46].

We did not find any association of depressive symptoms with socio-demographic factors except for the age of mothers. O’Hara and Swain (1996) found that poor marital relationships and low social support were significantly associated with depressive symptoms [4]. A previous study in Nepal showed significant association of depressive symptoms with low income, maternal occupation and low social status [17].

The screening of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers with pregnancy-induced health problems [47,48] and/or subjective feelings of stress are the programmatic implications of this study. Our study has a number of limitations. The EPDS tool used in this study is only a symptomatic assessment for depressive symptoms without a clinical diagnosis. We cannot rule out the possibility of recall bias of the respondents reported information. Having selected an immunization clinic as our setting, the findings from this study might not be generalizable to the community setting. While there is growing evidence that smoking and alcohol affect maternal and child health, we did not collect data on these variables, which could be seen as a major limitation of this study. Further research in this area should explore the role of pregnancy complications, smoking and alcohol use on depressive symptoms among mothers, and be carried out among a representative population, using a robust study design.

Conclusions

About one-third of post-partum mothers attending the immunization clinic at a maternity hospital in Nepal had reported depressive symptoms. Pregnancy-induced health problems and stress during pregnancy were associated with occurrence of PPD symptoms. The screening of depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers who have pregnancy-induced health problems and subjective feelings of stress during pregnancy should be included in routine maternity care services.

References

World Health Organization. Maternal Mental health and Child Health and Development in Low and Middle Income Countries. Geneva: 2008.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6.

Vivilaki VG, Dafermos V, Kogevinas M, Bitsios P, Lionis C. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: translation and validation for a Greek sample. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:329.

O’hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

Beck CT. The lived experience of postpartum depression: a phenomenological study. Nurs Res. 1992;41(3):166–70.

Klainin P, Arthur DG. Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1355–73.

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva: 2004.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-text Revision (DSM-IV-TRim, 2000). Arlington, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa. Indian Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):43–7.

Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India. Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:499–504.

Mehta S, Mehta N. An overview of risk factors associated to post-partum depression in Asia. Ment Ill. 2014;6(1):5370. doi:10.4081/mi.2014.5370.

Wisner KL, Chambers C, Sit DK. Postpartum depression: a major public health problem. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2616–8.

Fisher J, Mello MCD, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(2):139–49.

Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Woolgar M, Murray L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175(6):554–8.

Chaaya M, Campbell OMR, El Kak F, Shaar D, Harb H, Kaddour A. Postpartum depression: prevalence and determinants in Lebanon. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002;5(2):65–72.

DØRheim Ho†Yen S, Tschudi Bondevik G, Eberhard†Gran M, Bjorvatn BR. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among postnatal women in Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(3):291–7.

Clarke K, Saville N, Shrestha B, Costello A, King M, Manandhar D, et al. Predictors of psychological distress among postnatal mothers in rural Nepal: a cross-sectional community-based study. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:76–86.

Ludermir AB, Lewis G, Valongueiro SA, de Araújo TVB, Araya R. Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):903–10.

Secco ML, Profit S, Kennedy E, Walsh A, Letourneau N, Stewart M. Factors affecting postpartum depressive symptoms of adolescent mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(1):47–54.

Reid V, Meadows-Oliver M. Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers: an integrative review of the literature. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21(5):289–98.

Budhathoki N, Bhusal S, Ojha H, Basnet S. Violence against women by their husband and postpartum depression. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2013;10(22):176–80.

Pradhan A, Suvedi BK, Barnett S, Sharma SK, Puri M, Poudel P, et al. Nepal Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study 2009. Kathmandu: Family Health Division; 2010.

Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87.

Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209.

Sabba NR. Post Partum Depression among Rajbansi Women in Nepal. Researcher Res J Culture Society. 2013;1(1):63–71.

DØRheim Ho†Yen S, Tschudi Bondevik G, Eberhard†Gran M, Bjorvatn B. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the postnatal period in Lalitpur district, Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(10):1186–92.

Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP). Annual report. Kathmandu: Department of Health Services; 2011.

Lee DT, Yip AS, Leung TY, Chung TKH. Identifying women at risk of postnatal depression: prospective longitudinal study. Hong Kong Med J. 2000;6(4):349–54.

Regmi S, Sligl W, Carter D, Grut W, Seear M. A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7(4):378–82.

Nepal M, Sharma V, Koirala N, Khalid A, Shresta P. Validation of the Nepalese version of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in tertiary health care facilities in Nepal. Nep J Psychiatry. 1999;1:46–50.

Ghubash R, Abou-Saleh MT, Daradkeh TK. The validity of the Arabic Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(8):474–6.

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350–64.

Dahal DR. Social composition of the population: caste/ethnicity and religion in Nepal. Population Monograph Nepal. 2003;1:87–135.

Ministry of Health and Population. Annual report. Kathmandu: Department of Health Services; 2012.

Bairwa M, Rajput M, Sachdeva S. Modified kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: social researcher should include updated income criteria, 2012. Indian J Commun Med. 2013;38(3):185–91.

Sword W, Landy CK, Thabane L, Watt S, Krueger P, Farine D, et al. Is mode of delivery associated with postpartum depression at 6 weeks: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2011;118(8):966–77.

Lanes A, Kuk JL, Tamim H. Prevalence and characteristics of postpartum depression symptomatology among Canadian women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:302.

Inandi T, Elci OC, Ozturk A, Egri M, Polat A, Sahin TK. Risk factors for depression in postnatal first year, in eastern Turkey. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1201–7.

Goker A, Yanikkerem E, Demet MM, Dikayak S, Yildirim Y, Koyuncu FM. Postpartum depression: is mode of delivery a risk factor? ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:616759. doi:10.5402/2012/616759.

Ayvaz S, Hocaoglu C, Tiryaki A, Ak I. [Incidence of postpartum depression in Trabzon province and risk factors at gestation]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2006;17(4):243–51.

McCoy SJ, Beal JM, Saunders B, Hill EN, Payton ME, Watson GH. Risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective investigation. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(3):166–70.

tion (MOHP) [Nepal], New ERA, ICF International Inc. Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal, Calverton, Maryland: Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA and ICF International; 2012.

Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, Lavand’homme P, Landau R, Houle TT. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140(1):87–94.

Josefsson A, Angelsiöö L, Berg G, Ekström C-M, Gunnervik C, Nordin C, et al. Obstetric, somatic, and demographic risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):223–8.

Gonidakis F, Rabavilas AD, Varsou E, Kreatsas G, Christodoulou GN. A 6-month study of postpartum depression and related factors in Athens Greece. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):275–82.

Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. CMAJ. 1996;154(6):785–9.

Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ. The onset of postpartum depression: implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(2):522–6.

Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2003;12(4):373–80.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Institute of Medicine, Tribhuwan University and all the participants who participated in this study. We are thanked to Subas Neupane, Rajendra Karkee, and Padam Simkhada who provided comments on the manuscript during revision. We are indebted to Vicktoria Nelin for her support in final editing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RKG designed the study, pre-tested the tools, carried out the field work and acquired the data. RBK drafted the manuscript, interpreted findings, reviewed the relevant literature and revised the manuscript. VK, SRM performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the findings, and contributed with a literature review. VDS, RPG carried out the literature review, supervised the project and contributed in writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript, read the final manuscript, and agreed on the final version.

Rajendra Kumar Giri, Resham Bahadur Khatri, Shiva Raj Mishra and Vishnu Khanal contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Giri, R.K., Khatri, R.B., Mishra, S.R. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers in Nepal. BMC Res Notes 8, 111 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1074-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1074-3