Abstract

Background

In adults with asthma, physical activity has been associated with several asthma outcomes. However, it is unclear whether changes in physical activity, measured via an accelerometer, have an effect on asthma control. The objective of the present study is, in adults with moderate-to-severe asthma, to investigate the effects of a behaviour change intervention, which aims to increase participation in physical activity, on asthma clinical control.

Methods

This is a single-blind (outcome assessor), two-arm, randomised controlled trial (RCT). Fifty-five participants with moderate-to-severe asthma, receiving optimized pharmacological treatment, will be randomly assigned (computer-generated) into either a Control Group (CG) or an Intervention Group (IG). Both groups will receive usual care (pharmacological treatment) and similar educational programmes. In addition to these, participants in the IG will undergo the behaviour change intervention based on feedback, which aims to increase participation in physical activity. This intervention will be delivered over eight sessions as weekly one-on-one, face-to-face 40-min consultations. Both before and following the completion of the intervention period, data will be collected on asthma clinical control, levels of physical activity, health-related quality of life, asthma exacerbation and levels of anxiety and depression symptoms. Anthropometric measurements will also be collected. Information on comorbidities, lung function and the use of asthma medications will be extracted from the participant’s medical records.

Discussion

If successful, this study will demonstrate that, in adults with asthma, a behavioural change intervention which aims to increase participation in physical activity also affects asthma control.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials.gov PRS (Protocol registration and Results System): NCT-03705702 (04/10/2018).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that is defined by a variable expiratory airflow limitation and by respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough [1]. People with asthma present paradoxical responses to physical activity. That is, although vigorous exertion induces exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB), regular physical activity may be useful in the management of asthma [2]. Of note, the fear of becoming short of breath deters many people with asthma from taking part in regular activities and sports with their peers [2, 3].

In both health and disease, lower participation in physical activity has been associated with greater morbidity and mortality [4, 5]. In people with asthma specifically, lower levels of physical activity have been associated with an increased risk of disease exacerbation, increased frequency of medical visits and higher health care utilization [2, 4]. Therefore, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommends that people with asthma engage in regular physical activity in order to improve their general health [1]. Several studies have reported the benefits of supervised exercise training on a broad range of outcomes in people with asthma such as disease exacerbation, clinical control, airway inflammation, psychosocial symptoms and exercise capacity [6,7,8,9,10,11]. These well-resourced studies may have limited application in regions that do not offer a program of supervised exercise training to people with asthma. Therefore, the current study plans to explore an alternative approach in which participants with asthma will engage in a behaviour change program which aims to increase participation in physical activity to produce health benefits and to improve asthma control.

Increasing participation in physical activity in daily life requires a conscious behaviour change [12]. According to some psychosocial models, behaviour change techniques that have shown promise build on participant confidence or self-efficacy to demonstrate the desired behaviour. Individual behaviour change techniques that have shown promise include; (i) education about why the change is worthwhile, (ii) action planning and, (iii) improving social support [13,14,15]. Therefore, behaviour interventions should include behaviour change techniques, such as self-monitoring, individual goal setting, feedback on behaviour, problem-solving coping planning and behaviour contract [16]. Others approaches (motivational interviewing) and considerations (managing relapses) are also important to overcome barriers and encourage adherence to the regimen [14, 17].

A significant number of studies have investigated the effects of behaviour interventions on physical activity in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [18]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only one study has investigated changes in physical activity in people with asthma [19]. At enrolment of that study, all patients were instructed in the benefits of physical activity, were given a pedometer, and made a contract to be more physically active. Patients in the intervention group also received instruction in linking positive affect and self-affirmation to physical activity. The authors concluded that a multiple-component protocol was effective at increasing physical activity in people with asthma, but an intervention to increase positive affect and self-affirmation was not effective within this protocol [19]. Despite the novelty of this study, we can consider it has two bias. First, it was conducted in people with mild to moderate asthma, who had minimal impairment in physical fitness and minimal number of comorbidities. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with more severe asthma seem to obtain the greatest benefit from exercise training [8, 20, 21]. Second, physical activity was quantified by using a questionnaire that can present a recall bias [19]. In addition, the study did not assess sedentary behaviour (SB), which has been associated with negative health consequences [22].

In the past several years, sedentary behaviour (SB) has received considerable attention due its association with the increased risk for all-cause mortality in the general population [22]. SB is defined as any activities or behaviours (other than sleep) that are characterized by low energy expenditure (≤ 1.5 MET, metabolic equivalent of task), including activities such as sitting, reclining or being in a lying position [23]. Even patients with COPD who perform the recommended 150-min of MVPA per week spent most of their time engaged in sedentary behaviour or in light intensity PA [24]. In patients with asthma, a higher sedentary time has been associated with decreased exercise capacity and asthma control [25]; however, strategies to reduce the time in SB in this population remains largely unknown.

The main objective of the present study is, in adults with moderate-to-severe asthma, to investigate the effects of a behaviour change intervention, which aims to increase participation in physical activity, on asthma clinical control. Changes in sedentary behaviour, sleep, health-related quality of life and psychosocial symptoms will be also evaluated to better understand how physical activity might influence asthma control. Our hypothesis is that the behaviour intervention will be effective at increasing physical activity levels and improving clinical control in adults with asthma.

Methods/design

Participants

The study will include adults, aged 18 to 60 years, with moderate or severe persistent asthma [1], clinically stable disease (without hospitalizations, emergency care or medication changes for at least 30 days), who have been undergoing medical treatment for at least 6 months [8]. Patients will be required to report that they are not meeting the current guidelines for sufficient physical activity (i.e. performing < 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week) [26] and should have uncontrolled asthma according to the asthma control questionnaire (i.e. ACQ score > 1.5) [27]. The exclusion criteria will comprise the presence of any underlying lung condition other than asthma; significant cardiovascular or musculoskeletal disease that may compromise the participant’s capacity to participate in physical activity; active cancer; and uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes. People who are participating in other research studies, those who are unable to understand our questionnaire, as well as pregnant women, smokers or ex-smokers (≥ 10 pack-years), will also be excluded.

Study setting

Participants will be recruited from an outpatient asthma clinic at a University Hospital in São Paulo. The Hospital Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo has approved the study (66375617.1.0000.0068), and all of the patients will provide written informed consent before participating. This study has been registered on Clinical Trials.gov PRS (Protocol registration and Results System): NCT-03705702 (04/10/2018).

Experimental design

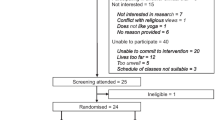

This is a single-blind (outcome assessor), two-arm, randomised controlled trial (RCT). Adults with asthma will be invited to participate in the study after a regular medical visit, and asthma pharmacotherapy will be maintained during the intervention. All of the eligible participants will be randomly assigned to either a control group (CG) or an intervention group (IG). Both groups will receive usual care (pharmacological treatment) and similar educational programmes. In addition to these, participants in the IG will undergo the behaviour intervention based on feedback, which aims to increase participation in physical activity. Both before and following the completion of the intervention period, data will be collected on asthma clinical control, levels of physical activity, health-related quality of life, asthma exacerbation, levels of anxiety and depression symptoms. Anthropometric measurements will also be collected. Information on comorbidities, lung function and the use of asthma medications will be extracted from the participant’s medical records. The protocol foresees has 12 weeks including 8 weeks of intervention and 4 weeks of evaluation (2 weeks before and 2 after the intervention). The study flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1 and the study schedule in Table 1.

Study flow diagram. Assessment will be performed during two visits. Eligible participants will be randomly assigned to either the Control Group (CG) or the Intervention Group (IG). Participants in both groups will receive the same educational program. In addition, participants in the IG will undergo the eight-week behaviour intervention aimed at increasing participation in physical activity. Re-assessment will occur following the completion of the intervention period

Randomisation and blinding

The randomisation sequence will be computer-generated and implemented by an investigator who is unaware of the sequence and is not involved in recruitment, assessment or treatment. The randomisation sequence will be concealed using opaque envelopes that are sequentially numbered as previously described [28]. Each envelope will correspond to one of the two study groups, and an envelope will be picked by the participant after the baseline assessments. The nature of the interventions will preclude the blinding of the participants and blinding of the physiotherapist who will deliver the education and behaviour intervention. However, the outcome and the statistic assessor will be blinded to group allocation.

Interventions

Educational programme

Participants in both the CG and the IG will complete a similar educational programme consisting of two 90-min classes, held in different weeks. The classes will include an education videotape, presentations and group discussions. The first class will address asthma education, which will include information about the pathophysiology of asthma, instructions on both medication and use of the peak flow meter, self-monitoring techniques, environmental control techniques and avoidance strategies [1, 29]. The second class will address the current international physical activity recommendations as well as the importance and benefits of being physically active and maintaining a healthy lifestyle [26].

Behaviour intervention

Participants in the IG will undergo a behaviour counselling programme, combined with a monitoring-and-feedback tool, which will aim to increase participation in physical activity. The behaviour intervention will be based on the transtheoretical model, which recognizes behaviour change as a dynamic process that moves through stages and that reinforces change via goal-setting, skill-development and self-control [14, 30]. Participants will be requested to attend eight one-on-one face-to-face goal-setting consultations, once a week, with each consultation lasting approximately 40 min. At the beginning of the intervention, a motivational interview will be conducted, in order to identify the physical activity behaviour stage the participant is at, by using a validated questionnaire [31]. Participants will be offered a commercially available activity monitor (wearable device), known as a Fitbit Flex 2 (Fitbit Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), to wear during the 3 days prior to each consultation. During each weekly consultation, data from the activity monitor will be downloaded and reviewed. An individual action plan, tailored according to each participant’s level of physical activity and behaviour change stage, will be established with realistic goals in order to increase the time spent in physical activity. After 3 weeks of intervention, discussion about sedentary behaviour will be implemented to raise awareness of the risks of prolonged uninterrupted periods of sitting in order to reduce time spent sedentary (i.e. sitting, reclining or lying during waking hours). Participants will be asked to complete a physical activity diary (daily book) and sign a contract with the health professional in order to commit to an action plan.

Weekly physical activity goals will be set using data provided by the “Fitbit”, using the behaviour change techniques such as self-monitoring, individual goal setting, feedback on behaviour, problem-solving coping planning, behaviour contract, as also others approach (motivational interviewing) and considerations (managing relapses) [13,14,15,16]. During the last eight consultation, participants will be interviewed in order to identify the any change in behaviour stage as well as to discuss the goals that have been achieved, the benefits of participating in the behaviour intervention, the strategies that were used to overcome barriers to physical activity and the long-term goals that will be used to remain physically active. The schedule and content of each individual session are summarized in Table 2.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Asthma clinical control

Asthma clinical control will be measured using the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ). The ACQ, a reliable and validated tool [32, 33] that consists of five questions related to asthma symptoms (daytime and night-time symptoms, activity limitations, dyspnoea and wheezing), one question on rescue medication (the use of short-acting β2 agonists) and one question on lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1] before bronchodilation expressed as a percent of the predicted value). The score of the ACQ ranges between 0 and 6. Scores lower than 0.75 are associated with good asthma control, whereas scores greater than 1.5 are indicative of poorly controlled asthma [27]. A change of at least 0.5 points in the ACQ score is regarded as being clinically significant [34].

Secondary outcomes

Levels of physical activity and sleep

Levels of physical activity and sleep will be objectively measured by an accelerometer (Actigraph GT9X, Actigraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) [35]. The device will be initialized via a computer interface in order to collect data in 60-s epochs on the 9 axes by using specific software (ActiLife 6.13.3 Firmware version). Each participant will be instructed to wear the device, on the waist (using an elastic belt) during the day and on the non-dominant wrist at night, for seven consecutive days both before and following the completion of the intervention period. Data will be presented as the average number of steps per day (steps/day), as well as the time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activities (MVPA, minutes/day) (≥ 1951 cpm), light-intensity physical activity (≥ 100 and < 1951 cpm) and time spent sedentary (< 100 cpm), expressed as the percentage of waking hours. The outcomes derived from the sleep monitor will be sleeping latency (the amount of time needed to fall asleep) and sleep efficiency (number of sleep minutes divided by the total number of minutes the participant was in bed). The device is a valid and reliable method for detecting sleep/wake diurnal patterns compared with polysomnography [36].

Asthma-related quality of life

Health-related asthma quality of life will be assessed by the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ). The AQLQ comprises four domains: activity limitations, symptoms, emotional function and environmental stimuli. The AQLQ has been translated into Portuguese and validated in a Portuguese-speaking population [37]. The AQLQ score ranges between 0 and 7 and the higher the score, the better the quality of life. An improvement of 0.5 points following intervention is considered to be clinically significant [38].

Asthma exacerbation

Asthma exacerbation is defined as the occurrence of events that are troublesome to the patient or that require urgent action on the part of the patient and physician, thus prompting a need for a change in treatment [39]. At least one of the following criteria will be used to define an exacerbation during the current study: the use of ≥4 puffs of rescue medication per 24 h during a 48-h period; a need for systemic corticosteroids; an unscheduled medical appointment and either a visit to an emergency room or a hospitalization [29, 39].

Anxiety and depression symptoms

Symptoms of anxiety and depression will be assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [40], which consists of 14 items divided into 2 subscales (7 for anxiety and 7 for depression). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, with a maximum score of 21 points for each subscale. The HADS uses a cut-off score to classify participants as having or not having symptoms of anxiety or depression (score > 9 each) [41].

Anthropometric indexes

Height, body-weight (Filizola®, Brazil), waist circumference, hip circumference and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) will be measured by using a standardized protocol [42, 43]. Participants body mass index (BMI) will be obtained by dividing body-weight (in kilograms) by their height (in metres squared) [44].

Data analysis

A sample of 46 participants has been estimated as the number needed to provide 80% power in order to detect a between-group difference (favouring the IG) of 0.5 ± 0.7 in the ACQ score (effect size of 0.7) [34]. The final sample size will be set at 55 patients, assuming up to a 20% loss during follow-up, as described previously [8, 29]. The results will be analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle, as recommended by the CONSORT statement [45], using specific software (SigmaStat 3.5, Systat Software Inc.). The distribution of the data for the continuous outcomes will be assessed using the Shapiro Wilk test. Data that are not normally distributed will be transformed, and a repeated measure ANOVA will be used to test the interactions between time and treatment. A Holm-Sidak correction will be applied in order to adjust for multiple comparisons. P values < 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Trial status

Recruitment commenced early in October 2018, and it is expected that recruitment will take approximately 6 months to complete, with final data collection occurring in November 2019.

Discussion

In the recent years, there is a growing scientific interest about the benefits of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, especially in regard to chronic respiratory diseases [18, 46]. This interest has been driven, at least in part, by several studies in people with COPD that have shown an association between low levels of physical activity and poor health outcomes [18]. Improvements in physical fitness has been shown to have beneficial effects on the general health of subject with asthma [6]. However, most of them also avoid taking part in regular activities and sports due to fear of worsening of their asthma symptoms [47]. Therefore, studies investigating interventions aimed at increasing levels of physical activity remain less explored in patients with asthma.

The most recent Cochrane review investigating the role of exercise training in people with asthma, demonstrated that aerobic exercise was effective at improving physical fitness, health-related quality of life and asthma symptoms [6]. However, the effect of levels of physical activity was unclear. Of note, despite the strong evidence that pulmonary rehabilitation (which includes exercise training) improves several outcomes in people with COPD including symptoms, health-related quality of life and exercise capacity, people present minimal, if any, change in levels of physical activity following the completion of the program [48, 49]. This result is not surprising because pulmonary rehabilitation programmes aim to improve functional capacity and symptoms, but do not include specific elements that are designed to modify daily behaviour [49]. This hypothesis is supported by a recent review that demonstrated that physical activity counselling interventions in people with COPD are likely to be more successful in modifying physical activity than rehabilitation programmes [18].

Outside the framework of pulmonary rehabilitation, there has been considerable interest in other strategies that improve physical activity in people with COPD. For example, physical activity counselling has been shown to be a very promising intervention in improving physical activity levels of people with COPD [18]. Some of the key components of physical activity counselling are self-monitoring of daily activities, coaching and goal-setting based on relative increases in baseline background activity, along with feedback via an activity monitor [49]. Activity monitors that provide feedback to users have been considered to be effective in increasing physical activity in many counselling interventions [50, 51]. In addition, there is similar technology for the self-monitoring the time spent in sedentary behaviour via visual and vibrotactile feedback [52]. Of note, the effects of physical activity counselling have not been investigated in people with asthma.

Although there is evidence suggesting that people with asthma who have higher levels of physical activity present with better health outcomes, it is unknown whether an intervention aimed at changing participation in physical activity is a potential nonpharmacological approach for asthma clinical control. Therefore, the results of the proposed study have the potential to contribute significantly to improving the management of people with moderate-to-severe asthma symptoms.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACQ:

-

Asthma control questionnaire

- AQLQ:

-

Asthma-related quality of life

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CG:

-

Control group

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- EIB:

-

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction

- GINA:

-

Global Initiative for Asthma

- IG:

-

Intervention group (IG)

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent of task

- MVPA:

-

Moderate and vigorous physical activity

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SB:

-

Sedentary behaviour

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratios

References

Global Initiative fos ashtma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Bathesda: National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of Health; 2018. https://www.ginasthma.org. Accessed 21 Sept 2018

Cordova-Rivera L, Gibson PG, Gardiner PA, McDonald VM. A systematic review of associations of physical activity and sedentary time with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(6):1968-81.

van't Hul AJ, Frouws S, van den Akker E, van Lummel R, Starrenburg-Rzaemberg A, van Bruggen A, et al. Decreased physical activity in adults with bronchial asthma. Respir Med. 2016;114:72–7.

Garcia-Aymerich J, Varraso R, Anto JM, Camargo CA Jr. Prospective study of physical activity and risk of asthma exacerbations in older women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(11):999–1003.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29.

Carson KV, Chandratilleke MG, Picot J, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Smith BJ. Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD001116.

Dogra S, Kuk JL, Baker J, Jamnik V. Exercise is associated with improved asthma control in adults. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(2):318–23.

Franca-Pinto A, Mendes FA, de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Agondi RC, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Aerobic training decreases bronchial hyperresponsiveness and systemic inflammation in patients with moderate or severe asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70(8):732–9.

Freitas PD, Ferreira PG, da Silva A, Trecco S, Stelmach R, Cukier A, et al. The effects of exercise training in a weight loss lifestyle intervention on asthma control, quality of life and psychosocial symptoms in adult obese asthmatics: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:124.

Freitas PD, Silva AG, Ferreira PG, Da Silva A, Salge JM, Carvalho-Pinto RM, et al. Exercise improves physical activity and comorbidities in obese adults with asthma. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(7):1367–76.

Mendes FA, Goncalves RC, Nunes MP, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;138(2):331–7.

King AC, Blair SN, Bild DE, Dishman RK, Dubbert PM, Marcus BH, et al. Determinants of physical activity and interventions in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(6 Suppl):S221–36.

Anderson ES, Wojcik JR, Winett RA, Williams DM. Social-cognitive determinants of physical activity: the influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation among participants in a church-based health promotion study. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):510–20.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP, Vranizan KM, Taylor CB, Solomon DS. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Prev Med. 1986;15(4):331–41.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Cavalheri V, Straker L, Gucciardi DF, Gardiner PA, Hill K. Changing physical activity and sedentary behaviour in people with COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(3):419–26.

Mantoani LC, Rubio N, McKinstry B, MacNee W, Rabinovich RA. Interventions to modify physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):69–81.

Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Wenderoth S, Hollenberg JP, Wells MT, et al. Increasing physical activity in patients with asthma through positive affect and self-affirmation: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):337–43.

Dias-Junior SA, Reis M, de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Stelmach R, Halpern A, Cukier A. Effects of weight loss on asthma control in obese patients with severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1368–77.

Neder JA, Nery LE, Silva AC, Cabral AL, Fernandes AL. Short-term effects of aerobic training in the clinical management of moderate to severe asthma in children. Thorax. 1999;54(3):202–6.

Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):123–32.

Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14(1).

Hill K, Gardiner PA, Cavalheri V, Jenkins SC, Healy GN. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour: applying lessons to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med J. 2015;45(5):474–82.

Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Briggs WM, Wenderoth S, Charlson ME. Measuring physical activity in asthma patients: two-minute walk test, repeated chair rise test, and self-reported energy expenditure. J Asthma. 2007;44(4):333–40.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–59.

Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, Bateman ED, Committee G. Identifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the asthma control questionnaire. Respir Med. 2006;100(4):616–21.

Ribeiro MA, Martins MA, Carvalho CR. Interventions to increase physical activity in middle-age women at the workplace: a randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(5):1008–15.

Freitas PD, Ferreira PG, Silva AG, Stelmach R, Carvalho-Pinto RM, Fernandes FL, et al. The role of exercise in a weight-loss program on clinical control in obese adults with asthma. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(1):32–42.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–5.

Ribeiro MA, Martins Mde A, Carvalho CR. The role of physician counseling in improving adherence to physical activity among the general population. Sao Paulo Med J. 2007;125(2):115–21.

Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):902–7.

Leite M, Ponte EV, Petroni J, D'Oliveira Junior A, Pizzichini E, Cruz AA. Evaluation of the asthma control questionnaire validated for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(10):756–63.

Juniper E, Stahl E, O’Byrne P. Minimal important difference for the asthma control questionnaire. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:642(A).

Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S531–43.

Cellini N, Buman MP, McDevitt EA, Ricker AA, Mednick SC. Direct comparison of two actigraphy devices with polysomnographically recorded naps in healthy young adults. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(5):691–8.

De Oliveira MA, Barbiere A, Santos LA, Faresin SM, Fernandes AL. Validation of a simplified quality-of-life questionnaire for socioeconomically deprived asthma patients. J Asthma. 2005;42(1):41–4.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(1):81–7.

Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, Boushey HA, Busse WW, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):59–99.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, Garcia C Jr, Pereira WA. Mood disorders among inpatients in ambulatory and validation of the anxiety and depression scale HAD. Rev Saude Publica. 1995;29(5):355–63.

Gordon CC, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Stature, recumbent length and weigth. In: Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1988. p. 3–8.

Keenan NL, Strogatz DS, James SA, Ammerman AS, Rice BL. Distribution and correlates of waist-to-hip ratio in black adults: the Pitt County study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(6):678–84.

Bray GA. Classification and evaluation of the obesities. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73(1):161–84.

Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, Group C. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285(15):1992–5.

Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Anto JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–8.

Mancuso CA, Sayles W, Robbins L, Phillips EG, Ravenell K, Duffy C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthy physical activity in asthma patients. J Asthma. 2006;43(2):137–43.

Cindy Ng LW, Mackney J, Jenkins S, Hill K. Does exercise training change physical activity in people with COPD? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(1):17–26.

Langer D, Demeyer H. Interventions to modify physical activity in patients with COPD: where do we go from here? Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):14–7.

Mendoza L, Horta P, Espinoza J, Aguilera M, Balmaceda N, Castro A, et al. Pedometers to enhance physical activity in COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(2):347–54.

Kawagoshi A, Kiyokawa N, Sugawara K, Takahashi H, Sakata S, Satake M, et al. Effects of low-intensity exercise and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation with pedometer feedback on physical activity in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2015;109(3):364–71.

Ryde GC, Gilson ND, Suppini A, Brown WJ. Validation of a novel, objective measure of occupational sitting. J Occup Health. 2012;54(5):383–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the patients and health professionals who will participate in this trial and also the Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq) for the financial support.

Funding

The study is supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; Phone: + 55 11 3838–4000) and by the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq; Phone: 55 61 32114000). The grant CNPq 311443/2014–1 support the scholarship of CRFC as well as the patient’s transport and equipment while the grant FAPESP 2016/17093–0 support the Postdoctoral Research Scholarship of PDF. VC is supported by the Cancer Council of Western Australia Postdoctoral Research Fellowship. The authors declare that the funders have no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PDF: significant manuscript write and review, study concept and design; RFX, NFPP, RMCP, AC and RS: substantial contribution to the design of this trial and manuscript review; MAM: project supervision, manuscript review; VC and KH: study design; manuscript review; CRFC: project supervision, manuscript write and review, study concept and design; overall study coordination. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This protocol is approved by the Hospital Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sao Paulo (66375617.1.0000.0068). The study methodology was documented in a protocol and registered in Clinical Trials.gov PRS (Protocol registration and Results System): NCT-03705702 on 4 October 2018 prior to starting recruitment. All participants are given verbal and written information about the study and have to provide signed consent to participate in the research. The information collected about participants is individually identifiable by members of the research team only. Each participant will be allocated a unique numeric code (ID Number) such that all stored electronic data (e.g., databases, data files) will not contain identifiable data until the completion of the study. All confidential information is stored in locked filing cabinets, and only deidentified data will be presented or published.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Freitas, P.D., Xavier, R.F., Passos, N.F.P. et al. Effects of a behaviour change intervention aimed at increasing physical activity on clinical control of adults with asthma: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 11, 16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-019-0128-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-019-0128-6