Abstract

Background

Contradictory relationships have been observed between thyroid function and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Previous studies have indicated that pre-pregnancy BMI (pBMI) could modify their relationships. Few studies have illustrated the role of thyroid hormone sensitivity on GDM. We aimed to explore the effect of pre-pregnancy obesity on the association between early pregnancy thyroid hormone sensitivity and GDM in euthyroid pregnant women.

Methods

This study included 1310 women with singleton gestation. Subjects were classified into pre-pregnancy obese and non-obese subgroups by pBMI levels with a cutoff of 25 kg/m2. Sensitivity to thyroid hormone was evaluated by Thyroid Feedback Quartile-Based Index (TFQI), Chinese-referenced parametric TFQI (PTFQI), TSH Index (TSHI) and Thyrotrophic T4 Resistance Index (TT4RI). The associations between these composite indices and GDM were analyzed using multivariate regression models in the two subgroups, respectively.

Results

In pre-pregnancy non-obese group, early pregnancy TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI and TT4RI levels were higher in subjects with incident GDM compared to those without GDM (all P < 0.05). By contrast, obese women with GDM exhibited lower levels of those indices (all P < 0.05). The occurrence of GDM were increased with rising TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI and TT4RI quartiles in non-obese women ( all P for trend < 0.05), while exhibited decreased trend across quartiles of those indices in obese women (all P for trend < 0.05). Further logistic analysis indicated contrary relationships between thyroid hormone sensitivity and the occurrence of GDM in the two groups, respectively. The OR of the fourth versus the first quartile of TFQI for GDM was 1.981 (95% CI 1.224, 3.207) in pre-pregnancy non-obese group, while was 0.131 (95% CI 0.036, 0.472) in pre-pregnancy obese group. PTFQI and TSHI yielded similar results.

Conclusions

The association between maternal sensitivity to thyroid hormones during early gestation and the occurrence of GDM was modified by pre-pregnancy obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal thyroid function during the first trimester plays a vital role in maternal metabolism [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Numerous studies have disclosed definite influences of abnormal first-trimester thyroid function on adverse maternal complications [1, 3, 4, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, recent studies indicated that even variation in thyroid parameters within the normal range during the first trimester was related to adverse pregnancy outcomes [14,15,16].

Recently, The indices for assessment of central sensitivity to thyroid hormones, namely Thyroid Feedback Quantile-Based Index (TFQI), parametric TFQI (PTFQI), TSH index (TSHI) and thyrotrophic T4 resistance index (TT4RI), which were calculated by combination of both TSH and FT4, have proven to be more representative of thyroid homeostasis than single parameter [17,18,19]. Growing studies have revealed the association between these composite indices and metabolic-related diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and NAFLD, even in euthyroid populations [17, 19,20,21]. Our previous studies also revealed close links between those indices and lipid disorders in euthyroid populations [22, 23]. However, limited studies have evaluated those composite indices with pregnancy outcomes, especially those related to maternal energy balance, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

As a common obstetric metabolic disorder, GDM poses both short- and long-term threats to maternal and child health [11, 24]. So far, contradictory conclusions have been drawn to illustrate the causality between thyroid function and the occurrence of GDM [11, 25, 26]. For example, both hypothyroidism (overt/subclinical/isolated) and hyperthyroidism have been reported to be associated with GDM [9, 10, 27]. Some studies have indicated adverse relationships of FT4, TSH or both with GDM under euthyroid status [4, 11, 25], whereas other studies indicated contrary relationships [7, 11, 25]. These inconsistencies indicated complex relationships between the thyroid system and glucose homeostasis, which could hardly be explained by a single parameter. Although central thyroid hormone sensitivity has been illustrated to be closely associated with DM in non-pregnant population, few studies have explored their relationships in pregnant women.

The pre-pregnancy body mass index (pBMI) is a well-known determinant on pregnancy outcomes [28, 29]. Pregnancy obesity is an important risk factor for GDM [5, 30, 31]. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated a modifying role of pBMI on the association between thyroid hormones and pregnancy outcomes [29, 32]. It remains unclear whether pBMI could also modify the effect of sensitivity to thyroid hormones during early pregnancy on GDM. Therefore, our aim was to assess the relationships between sensitivity to thyroid hormones and GDM under pre-pregnancy obese and non-obese status, and further decipher the effect of pre-pregnancy obesity on their relationships in euthyroid women from Northern China.

Materials and methods

Study population

2102 pregnant women who underwent prenatal check-ups and delivery during January 2020 and December 2021 at Beijing Chao-yang Hospital were enrolled in this study. Subjects without OGTT results (n = 9), with pre-existing diabetes and hypertension (n = 12), with malignancy (n = 9), pituitary tumor (n = 4), infection diseases (n = 3), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (n = 27), fatty liver disease (FLD) (n = 15), connective tissue disease (CTD) (n = 14), multiple pregnancies (n = 10), without thyroid function test during first trimester (n = 565), with thyroid disease/surgery histories (n = 17), with thyroid (interfering) medication usage (n = 28), and with abnormal thyroid function (n = 79 ) were excluded. The final analysis contained 1310 individuals (Fig. 1). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-yang Hospital (Approval number: 2022 − 517). All participants signed the written informed consent.

Data Collection and parameters measurements

Medical history, drug usage, maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy weight and height were obtained during first clinical visit. Blood samples were collected during the first trimester (between 9 and 13 weeks) after overnight fasting. Maternal serum FT3, FT4, TSH, anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (TG-Ab) and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) were measured with chemiluminescence immunoassay (ADVIA Centaur XP, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Germany). Biochemical parameters including triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and uric acid (UA) were detected with Siemens Advia 2400 autoanalyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Germany). The OGTT test was conducted during the third trimester (24–28 weeks) by oral intake of a 75 g glucose load after fasting overnight. Plasma glucose levels were detected before and during 1 and 2 h of the OGTT test.

Variables definition

The guidelines on diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum by Chinese Medical Association recommended to establish population-based, trimester-specific, and assay method-specific thyroid hormone reference intervals for gestational women [33, 34]. Here, euthyroid during early pregnancy was defined as TSH (0.13–3.93 µIU/mL) and FT4 (12.00-23.34 pmol/L) within the reference ranges according to a previous national survey conducted in Chinese pregnant women by using the same thyroid hormones detection method [33, 35]. TFQI = cumulative distribution function (cdf) FT4 – (1 – cdf TSH). PTFQI = Φ((FT4 − µFT4)/σFT4) − (1 − Φ((ln TSH − µLn TSH)/σln TSH)), where µFT4 = 16.1372 (pmol/L), σFT4 = 1.90549, µln TSH = 0.1013 (µIU/mL), and σln TSH = 0.66922 for the Chinese pregnant women during the first trimester. TSHI, TT4RI and FT3/FT4 ratio were calculated as described previously [22].

pBMI was calculated as previously described [5]. Participants were classified into obese and non-obese subgroups according to the WHO classification for Asian population with a pBMI cutoff of 25 kg/m2 [36]. GDM was diagnosed if fasting plasma glucose ≥ 91.8 mg/dL or 1 h plasma glucose levels ≥ 180.0 mg/dL or 2 h glucose levels ≥ 153.0 mg/dL based on the OGTT test [24]. eGFR, pre-pregnancy hypertension, diabetes and FLD were defined according to previous studies [37].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (upper and lower quartiles) following normality detection by Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were expressed as number (proportion). Data difference between two groups were compared by unpaired Student’s t test, Mann-Whitney U test or the Chi-square test.

The correlation between indices of thyroid system and plasma glucose concentration during OGTT test were detected by Spearman analysis. Logistic regression analyses was conducted to explore the associations between per SD increase of thyroid indices and GDM in pre-pregnancy obese and non-obese women, separately. Model 1 was without adjustment, Model 2 was adjusted for age, parity, first trimester TG, LDL-C, UA and eGFR. The interactions between thyroid sensitivity indices and pre-pregnancy obesity on the occurrence of GDM were further analyzed. The four composite Indices were then divided into quartiles (Q) (TFQI:Q1 < -0.24, -0.24 ≤ Q2 < -0.01, -0.01 ≤ Q3 < 0.24, 0.24 ≤ Q4; PTFQI: Q1 < -0.23, -0.23 ≤ Q2 < 0.00, 0.00 ≤ Q3 < 0.25, 0.25 ≤ Q4;TSHI:Q1 < 1.89, 1.89 ≤ Q2 < 2.35, 2.35 ≤ Q3 < 2.72, 2.72 ≤ Q4; TT4RI:Q1 < 12.00, 12.00 ≤ Q2 < 19.58, 19.58 ≤ Q3 < 28.01, 28.01 ≤ Q4). The linear trends of the proportions of GDM across thyroid indices quartiles were analyzed by the Cochran Armitage trend test. The associations of thyroid parameters quartiles with GDM were explored by binary logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, parity, first-trimester TG, LDL-C, UA and eGFR.

The IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 27 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was applied in the current analysis and two-tailed P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for this study. Smoking and drinking were not taken as confounders due to the small proportion of women with smoking or alcohol consumption habits [29].

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

As shown in Table 1, the proportion of GDM was 17.2% for the whole population. Compared to non-GDM group, the GDM group exhibited older age, higher pBMI levels, shorter gestational week and higher first-trimester TG, TC, LDL-C levels (all P < 0.001). There were no statistical difference in composite indices of thyroid hormone sensitivity between women in GDM and non-GDM groups. The subjects were the categorized into pre-pregnancy non-obese and obese subgroups according to pBMI levels (Supplementary Table 1). Compared to pre-pregnancy non-obese group, the obese group exhibited not only older age, longer gestational week, higher first-trimester TG, TC, LDL-C levels but also higher proportion of GDM (all P < 0.05). Although TSHI and TT4RI were higher in obese group compared to non-obese group, no statistical difference of the TFQI and PTFQI was observed between the two groups.

Characteristic of participants with GDM stratified by pBMI

We then explore the difference between GDM and non-GDM women in pre-pregnancy obese and non-obese group, separately. As shown in Table 2, in non-obese group, women with GDM exhibited older age, higher pBMI levels, higher first-trimester serum lipid levels and UA levels (all P < 0.001). Additionally, women with GDM had higher TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI and TT4RI levels compared to non-GDM women (all P < 0.05), indicating a relative insensitivity to thyroid hormone status. Whereas in the obese group, women with or without GDM had comparable pBMI levels and serum lipid levels at the first trimester. It is noteworthy that, obese women with GDM exhibited lower levels of TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI and TT4RI levels compared to those without GDM (all P < 0.01), indicating a relative higher sensitivity to thyroid hormone status. Correlation analysis also indicated that TFQI (r = − 0.187), PTFQI (r = − 0.182) and TSHI (r = − 0.184) were negatively associated with OGTT-FBG levels only in obese group but not non-obese group, indicating a modifying effect of pre-pregnancy obesity on their relationships (Supplementary Table 2).

Association of indices of sensitivity to thyroid hormone with GDM

Next, we aimed to explore the contradictory associations between GDM and the indices of sensitivity to thyroid hormones. In pre-pregnancy non-obese women, the ORs for GDM were 1.250 (95% CI 1.056–1.478), 1.240 (95% CI 1.049–1.467) and 1.197 (95% CI 1.007–1.422)) for 1 SD increase in TFQI, PTFQI and TSHI after full adjustment (Table 3, all P < 0.05). On the contrary, in pre-pregnancy obese women, per SD increase in these composite indices were inversely associated with GDM (TFQI: OR: 0.474, 95% CI 0.303, 0.743; PTFQI: OR: 0.494, 95% CI 0.315, 0.774; TSHI: OR: 0.517, 95% CI 0.333, 0.802, TT4RI: OR 0.468, 95% CI 0.292, 0.752) (all P < 0.05). Further analysis verified significant interactions between TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI, TT4RI and pre-pregnancy obesity with respect to the GDM outcome (all P < 0.05).

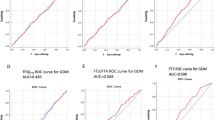

The composite indices of thyroid hormones were then divided into quartiles. As shown in Fig. 2, the proportion of GDM increased with increasing TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI and TT4RI quartiles in pre-pregnancy non-obese women (all P for trend < 0.05). However, in pre-pregnancy obese women, the prevalence of GDM exhibited decreased trend with rising quartiles of those indices (all P for trend < 0.05). As shown in Table 4, The Q3 to Q4 versus Q1 TFQI levels showed increasingly positive associations with GDM in non-obese women (Q3: OR 1.733, 95% CI 1.067–2.816; Q4: OR 1.981, 95% CI 1.224–3.207) (P for trend = 0.001). PTFQI and TSHI exhibited similar pattern. Instead, there was a negative correlation between the Q4 of TFQI, PTFQI, TSHI, TT4RI and GDM in obese women (all P for trend < 0.01).

The proportion of GDM by composite indices of sensitivity to thyroid hormones. (A) the proportion of GDM across TFQI quartiles in pre-pregnancy non- obese and obese subgroups; (B) the proportion of GDM across PTFQI quartiles in pre-pregnancy non-obese and obese subgroups; (C) the proportion of GDM across TSHI quartiles pre-pregnancy non-obese and obese subgroups; (D) the proportion of GDM across TT4RI quartiles pre-pregnancy non-obese and obese subgroups. Q1, the first quartile, Q2, the second quartile, Q3, the third quartile, Q4, the fourth quartile

Discussion

Our study yielded the following results. The indices of thyroid hormone sensitivity, TFQI, PTFQI and TSHI, during early pregnancy, were positively associated with the occurrence of GDM in pre-pregnancy non-obese women, while were negatively associated with GDM in pre-pregnancy obese women. Our results suggested a modifying effect of pre-pregnancy obesity on the association between early pregnancy thyroid hormone homeostasis and GDM.

Although thyroid hormone is precisely regulated through the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis, circulating concentration cannot fully reflect its actual effect [38, 39]. For example, some patients with hypothyroidism still show clinical symptoms, despite reaching the biochemical therapy targets after LT4 treatment, which was associated with the transition of FT4 to FT3 and the sensitivity of thyroid hormone [39]. In this study, four composite indices were adopted to evaluate central sensitivity to thyroid hormones. The TFQI and PTFQI were new indices proposed in recent years and were more accurate and stable in evaluating sensitivity to thyroid hormones compared to TSHI and TT4RI, which would be biased by the extreme value of FT4 and TSH [17]. They were closely related to adverse metabolic disorders, especially diabetes, as revealed in recent studies [17, 19]. However, only limited studies have explored their association with pregnancy outcomes.

Plenty of studies have confirmed the regulating role of the thyroid system on glucose homeostasis and GDM, although with inconsistent conclusions [4, 11]. Here, we uncovered contrary relationships between the indices of sensitivity to thyroid hormones and GDM under different pBMI status. This novel discovery indicated the complex interactions between pre-pregnancy energy status, hormone homeostasis and metabolic phenotype. Paradoxical results were also observed in non-pregnant population. Although studies have confirmed that reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormones (increased composite indices) was positively associated with diabetes and diabetes-related death [17, 19], no association between TFQI and new-onset diabetes was observed [19]. Moreover, one study indicated a protective role of reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormones on pre-diabetes in non-pregnant population [40]. In line with our findings under non-obese status, both FT4 and TSH have been shown to be associated with a higher risk of GDM [7, 25, 26, 41, 42]. However, an adverse relationship was observed under obese status. To our knowledge, there was only one study addressed a negative link between TFQI and GDM. However, they did not explore the modifying effect of pBMI [24]. In GDM women of non-obese group, reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormone was concomitant with a worse metabolic phenotype such as hyperlipidemia, higher BMI levels during early gestation. However, it appears that reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormones was an adaptable protective factor against energy oversupply under obese status, as the early pregnancy metabolic parameters among GDM and non-GDM subjects were comparable in addition to reduced resistance to thyroid hormones. Furthermore, most previous studies indicated a protective role of FT4 in the occurrence of GDM, indicating a complex modulation effect of thyroid homeostasis on glucose metabolism [4, 11, 26]. The discrepancy in both previous studies and our results may be attributed to the dual effects of thyroid hormones on glucose homeostasis, as it could not only lower glucose levels by increasing glucose utilization but also up regulate glucose levels by stimulating hepatic glycogenolysis and glucose intestinal absorption [24]. It is worth noting that, compared to non-pregnant population with diabetes, women with GDM had relatively less impaired glycemic control and energy imbalance. Collectively, further investigation is warranted for analyzing the contrary relationships in pregnant population.

Thyroid homeostasis itself could be modulated by obesity [43, 44]. For instance, the elevated TSH levels in obese premenopausal women could be reversed by weight loss or bariatric surgery [43]. Previous studies revealed inconsistent associations between thyroid hormone sensitivity and obesity. Some studies indicated a positive link of TFQI to obesity, while others indicated a reverse association between TFQI and BMI [17, 19, 45]. However, neither TFQI nor PTFQI but only TSHI and TT4RI were increased in obese women in our study. Iodine status may be a linker between pre-pregnancy energy status and thyroid hormone sensitivity, as previous studies have indicated a causal role of obesity for iodine deficiency. Previous studies also demonstrated compensated elevated thyroid sensitivity under iodine deficiency status [46, 47]. More importantly, iodine deficiency was associated with the occurrence of GDM [48]. Existing studies have also documented that adipocyte hormone such as leptin may be an underline modulator on the HPT axis under obesity status [24, 43].Therefore, further studies are warranted to take into account iodine status and hormones.

Plenty of evidence has documented causal effects of maternal thyroid homeostasis, pBMI and GDM on both obstetric complications and fetal health outcomes [49,50,51,52,53]. Hence, it is of vital significance to explore the pregnancy outcomes of GDM women with different thyroid hormone sensitivity and pBMI levels, which may deepen our understanding of GDM pathogenesis and add further guides for individualized GDM management. For example, previous study has indicated that GDM patients with underweight BMI encountered lower risk of preeclampsia and macrosomia and required a relaxed maternal glycemic target [54].

There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, this is a single-center retrospective study limited by small sample size and selection bias. Secondly, some confounders, such as socio-demographic characteristics, education, income levels and iodine intake, were not collected [46, 55]. Thirdly, there may be bias in pBMI as it was calculated based on self-reported pre-pregnancy body weight from pregnant women. Lastly, more than one measurement of maternal thyroid function could more accurate considering the variance in maternal thyroid hormones during the first trimester. Taken together, it will be necessary to validate our findings in more large-scale prospective studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found contrary associations between sensitivity to thyroid hormones and GDM modified by pre-pregnancy obesity. Our novel findings suggested complicated interactions between pBMI and thyroid hormone sensitivity on maternal complications and possibly fetal growth. More future studies are warranted to verify our findings and to further explore its influence on both maternal and fetal consequences.

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CTD:

-

connective tissue disease

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FT3:

-

free triiodothyronine

- FT4:

-

free thyroxine

- GDM:

-

gestational diabetes mellitus

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NAFLD:

-

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- pBMI:

-

pre-pregnancy BMI

- PCOS:

-

polycystic ovary syndrome

- PTFQI:

-

parametric TFQI

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TFQI:

-

thyroid feedback quantile-based index

- TG:

-

triglyceride

- TSH:

-

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- TSHI:

-

thyroid-stimulating hormone index

- TT4RI:

-

thyrotrophic T4 resistance index

- TG-Ab:

-

anti-thyroglobulin antibodies

- TPO-Ab:

-

anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody

References

Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):239–45.

Korevaar TI, Schalekamp-Timmermans S, de Rijke YB, et al. Hypothyroxinemia and TPO-antibody positivity are risk factors for premature delivery: the generation R study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4382–90.

Vrijkotte TG, Hrudey EJ, Twickler MB. Early maternal thyroid function during Gestation is Associated with fetal growth, particularly in male newborns. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):1059–66.

Yang S, Shi FT, Leung PC, et al. Low thyroid hormone in early pregnancy is Associated with an increased risk of gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4237–43.

Du MK, Ge LY, Zhou ML, et al. Effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on neonatal birth weight. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18(3):263–71.

Lee SY, Cabral HJ, Aschengrau A et al. Associations between maternal thyroid function in pregnancy and obstetric and perinatal outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(5).

Liu WY, Zhu YT, Xu XM, et al. Associations of thyroid function tests with lipid levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes during the First Trimester. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:973–81.

Zhu YD, Han Y, Huang K, et al. The impact of isolated maternal hypothyroxinaemia on the incidence of large-for-gestational-age infants: the Ma’anshan Birth Cohort study. BJOG. 2018;125(9):1118–25.

Ittermann T, Schipf S, Dorr M, et al. Hyperthyroxinemia is positively associated with prevalent and incident type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in two population-based samples from Northeast Germany and Denmark. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;28(2):173–9.

Gronich N, Deftereos SN, Lavi I, et al. Hypothyroidism is a risk factor for New-Onset Diabetes: a Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1657–64.

Chen GD, Gou XY, Pang TT, et al. Associations between thyroid function and gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Chinese pregnant women: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):44.

Furnica RM, Gruson D, Lazarus JH, et al. First trimester isolated maternal hypothyroxinaemia: adverse maternal metabolic profile and impact on the obstetrical outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(4):576–83.

Arbib N, Hadar E, Sneh-Arbib O, et al. First trimester thyroid stimulating hormone as an Independent risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(18):2174–8.

Gu Y, Su X, Li Y, et al. Do free thyroxine levels influence the relationship between maternal serum ferritin and gestational Diabetes Mellitus in early pregnancy? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;151:114–9.

Zhou B, Chen Y, Cai WQ, et al. Effect of Gestational Weight Gain on associations between maternal thyroid hormones and birth outcomes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:610.

Medici M, Timmermans S, Visser W, et al. Maternal thyroid hormone parameters during early pregnancy and birth weight: the Generation R Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):59–66.

Laclaustra M, Moreno-Franco B, Lou-Bonafonte JM, et al. Impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormones is Associated with Diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(2):303–10.

Werneck de Castro JP, Fonseca TL, Ueta CB, et al. Differences in hypothalamic type 2 deiodinase ubiquitination explain localized sensitivity to thyroxine. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):769–81.

Mehran L, Delbari N, Amouzegar A, et al. Reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormone is Associated with Diabetes and Hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(1):167–76.

Lai S, Li J, Wang Z, et al. Sensitivity to thyroid hormone indices are closely Associated with NAFLD. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:766419.

Yang S, Lai S, Wang Z, et al. Thyroid feedback quantile-based Index correlates strongly to renal function in euthyroid individuals. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):1945–55.

Sun H, Zhu W, Liu J et al. Reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormones is associated with high remnant cholesterol levels in Chinese euthyroid adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022.

Ding X, Wang Y, Liu J, et al. Impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormones is Associated with elevated homocysteine levels in the Euthyroid Population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(9):e3731–e7.

Liu ZM, Li G, Wu Y, et al. Increased central and peripheral thyroid resistance indices during the First Half of Gestation were Associated with lowered risk of gestational diabetes-analyses based on Huizhou Birth Cohort in South China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:806256.

Fernandez Alba JJ, Castillo Lara M, Jimenez Heras JM, et al. High first trimester levels of TSH as an Independent risk factor for gestational Diabetes Mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:13.

Gu Y, Li H, Bao X, et al. The relationship between thyroid function and the prevalence of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Euthyroid subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(2):434–42.

Wang C. The relationship between type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and related thyroid Diseases. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:390534.

Horng HC, Lee WL, Wang PH. Maternal weight gain and birth weight. J Chin Med Assoc. 2021;84(8):741–2.

Liu Y, Guo F, Zhou Y, et al. The interactive effect of Prepregnancy Overweight/Obesity and isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia on Macrosomia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(7):e2639–e46.

Song X, Chen L, Zhang S et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and High Triglyceride Levels Mediate the Association between Pre-pregnancy Overweight/Obesity and Macrosomia: a prospective cohort study in Central China. Nutrients. 2022;14(16).

Lewandowska M. Maternal obesity and risk of low Birth Weight, fetal growth restriction, and Macrosomia: multiple analyses. Nutrients. 2021;13(4).

Wang Y, Lu S, Xu X, et al. The interactive effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index, thyroid function, and blood lipid levels on the risk of gestational Diabetes Mellitus: a crossover analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):580.

Shan Z, Teng W, Liu X, et al. Guideline on diagnosis and management of thyroid Diseases during pregnancy and postpartum (2nd edition). Chin J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;35(8):636–65.

Shan Z, Teng W, Liu X, et al. Guideline on diagnosis and management of thyroid Diseases during pregnancy and postpartum (2nd edition). Chin J Perinat Med. 2019;22(8):505–39.

Yang L, Li M, Liu X, et al. Evaluation of Iodine Nutritional Status among pregnant women in China. Thyroid. 2020;30(3):443–50.

Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–63.

Sun H, Wang N, Chen C, et al. Cadmium exposure and its association with serum uric acid and hyperuricemia. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):550.

Roelfsema F, Boelen A, Kalsbeek A, et al. Regulatory aspects of the human hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;31(5):487–503.

Zhang QY, Ye XP, Zhou Z, et al. Lymphocyte infiltration and thyrocyte destruction are driven by stromal and immune cell components in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):775.

Liu B, Wang Z, Fu J, et al. Sensitivity to thyroid hormones and risk of prediabetes: a cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:657114.

Jun JE, Jee JH, Bae JC, et al. Association between changes in thyroid hormones and incident type 2 Diabetes: a seven-year longitudinal study. Thyroid. 2017;27(1):29–38.

Feldt-Rasmussen U, Effraimidis G, Klose M. The hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT)-axis and its role in physiology and pathophysiology of other hypothalamus-pituitary functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;525:111173.

Perello M, Cakir I, Cyr NE, et al. Maintenance of the thyroid axis during diet-induced obesity in rodents is controlled at the central level. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299(6):E976–89.

Kahr MK, Antony KM, DelBeccaro M, et al. Increasing maternal obesity is associated with alterations in both maternal and neonatal thyroid hormone levels. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84(4):551–7.

Juiz-Valina P, Cordido M, Outeirino-Blanco E et al. Central Resistance to thyroid hormones in morbidly obese subjects is reversed after bariatric surgery-Induced weight loss. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2).

Sun Y, Teng D, Zhao L et al. Iodine deficiency is associated with increased thyroid hormone sensitivity in individuals with elevated TSH. Eur Thyroid J. 2022;11(3).

Lecube A, Zafon C, Gromaz A, et al. Iodine deficiency is higher in morbid obesity in comparison with late after bariatric Surgery and non-obese women. Obes Surg. 2015;25(1):85–9.

Neven KY, Cox B, Cosemans C, et al. Lower iodine storage in the placenta is associated with gestational Diabetes Mellitus. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):47.

Lee SY, Cabral HJ, Aschengrau A, et al. Associations between maternal thyroid function in pregnancy and obstetric and perinatal outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(5):e2015–23.

Derakhshan A, Peeters RP, Taylor PN, et al. Association of maternal thyroid function with birthweight: a systematic review and individual-participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):501–10.

Vats H, Saxena R, Sachdeva MP, et al. Impact of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index on maternal, fetal and neonatal adverse outcomes in the worldwide populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15(6):536–45.

Howe CG, Cox B, Fore R, et al. Maternal gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Newborn DNA methylation: findings from the pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics Consortium. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(1):98–105.

Liu P, Xu L, Wang Y, et al. Association between perinatal outcomes and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index. Obes Rev. 2016;17(11):1091–102.

Kim M, Hur KY, Choi SJ, et al. Influence of Pre-pregnancy Underweight Body Mass Index on fetal abdominal circumference, estimated weight, and pregnancy outcomes in gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes & Metabolism Journal. 2022;46(3):499–505.

Ovadia YS, Zangen S, Rosen SR, et al. Maternal iodine deficiency: a newborns’ overweight risk factor? A prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(3):777–87.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants in this study for their contribution to this investigation.

Funding

This study was supported by Training Fund for Open Projects at Clinical Institutes and Departments of Capital Medical University (CCMU2022ZKYXZ004), Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital Golden Seeds Foundation (CYJZ202122) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82,200,938) to HS, the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA0806400) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX202106) to GW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. and Y.Z.: Methodology, data analysis, and writing original draft. J.L and Y.W. and G.W.: Conceptualization, supervision, review, and editing. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board at Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital (Approval number: 2022 − 517).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Zhou, Y., Liu, J. et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity modifies the association between first-trimester thyroid hormone sensitivity and gestational Diabetes Mellitus: a retrospective study from Northern China. Diabetol Metab Syndr 15, 212 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01188-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01188-6