Abstract

Background

Adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) have a high risk of developing depressive symptoms and diabetes-related distress (DD). Low socioeconomic level is associated with increased risk of poor self-management, treatment difficulties and psychological distress. The goals of this study were to document the frequency of major depressive disorder (MDD), high depressive symptoms and high DD, to assess levels of empowerment and to determine the association with each of these measures and glycemic control in a low-income Brazilian sample of adults with T1D.

Methods

In a cross-sectional study, inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and diagnosis of T1D > 6 months. Exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment, history of major psychiatric disorders, severe diabetes-related complications and pregnancy. Diagnoses of MDD were made using interview-based DSM-5 criteria. Depressive symptoms were evaluated by the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD-D). The Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS) assessed DD. Empowerment levels were evaluated by the Diabetes Empowerment Scale short form (DES-SF). Glycemic control was measured by HbA1c. The latest lipid panel results were recorded. Number of complications was obtained from medical records.

Results

Of the 63 T1D patients recruited, 36.5% were male, mean age was 31.5 (± 8.9), mean number of complications was 1 (± 1.1), and mean HbA1c was 10.0% (± 2). Frequency of MDD was 34.9% and 34.9% reported high depressive symptoms. Fifty-seven percent reported clinically meaningful DD. High diabetes regimen distress and low empowerment were associated to HbA1c (p = 0.003; p = 0.01, respectively). In multivariate analyses, lower empowerment levels were associated to higher HbA1c (beta − 1.11; r-partial 0.09; p value 0.0126). MDD and depressive symptoms were not significantly correlated with HbA1c in this expected direction (p = 0.72; p = 0.97, respectively).

Conclusions

This study showed high rates of MDD, high depressive symptoms and high DD and low levels of empowerment in this low income population. Empowerment and diabetes regimen distress were linked to glycemic control. The results emphasize the need to incorporate the psychological and psychosocial side of diabetes into strategies of care and education for T1D patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Abundant evidence has shown that adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) have a high risk for developing clinical depression and elevated depressive symptoms [1,2,3,4,5]. New research shows that over 40% of T1Ds experience elevated diabetes-related distress (DD) [6]. In order to maintain their glycemia at target levels, T1D patients need to monitor their blood glucose levels frequently and regularly, calculate and administer multiple daily insulin doses and address the effects of carbohydrate intake and exercise [7,8,9]. Living with T1D, the exhaustive demands of daily self-management and dealing with the possibility of developing chronic complications are associated with an increased risk of psychological distress [10, 11].

For patients with low incomes, the demands of managing T1D are even more challenging. These patients frequently do not have access to modern tools, diabetes education and other on-going support to assist them with disease management and to facilitate adaptive integration of their disease into every day life. Thus, low socioeconomic level is significantly associated with increased risk of poor self-management, treatment difficulties and psychological problems [12,13,14].

Diabetes education and psychosocial assessment are recommended as a critical part of patient-centered care in order to promote better diabetes outcomes and psychosocial well-being [15]. A great deal of research has documented the importance of a person-centered approaches in diabetes care, supporting the need for incorporating the cultural, social and psychological needs of T1D patients into patient education and clinical care [8, 15,16,17,18]. Empowerment is an effective model of person-centered education and care for people with T1D and may be particularly helpful for individuals with limited social and environmental resources [19,20,21,22,23].

In Brazil, almost 70% of T1D patients with low incomes receive their care in public tertiary care settings [12]. At State University of Campinas-Unicamp, the majority of T1D patients and their families have low incomes and are at high risk for developing clinical depression and/or DD. These patients experience considerable socio-economic stress and have few community resources to help them manage their disease.

In order to develop and implement an integrated psychosocial care program at Unicamp Diabetes Clinic that addresses the needs of T1D patients, we conducted a study to investigate the emotional burden of diabetes in this population. Our goal was to understand better the emotional side of T1D to help plan person-centered approaches for Brazilian T1D patients. The goals of this study were [1] to document the frequency of clinical depression, depression symptoms and DD, [2] to assess levels of empowerment, and [3] to determine the association between each of these measures and glycemic control in this low resource, Brazilian population of adults with T1D.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included patients with T1D receiving outpatient care at the type 1 diabetes clinic of the University of Campinas tertiary care clinic.

Inclusion criteria were age 18 and older and diagnosis of T1D for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment that could affect the patients’ ability to answer the protocol questions, history of major psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia, drug addiction, dementia), patients with severe diabetes-related complications (blindness, need for hemodialysis, limb amputations, and stroke) and pregnancy.

Patients were interviewed between December 2015 and December 2016 and were invited to take part in the study during routine consultations. Patients who consented to take part in the study gave permission for their clinical, laboratory and demographic data to be recorded. This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University Ethics in Research Committee in December 2015 (CAAE number: 50864815.4.0000.5404).

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) was made by the senior author based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association 2013 [24], in a face-to-face interview. Those diagnosed with MDD were so informed and were referred to the psychiatric service at Unicamp or to other psychiatric services in the community if they were not presently under care.

Evaluation of depressive symptoms was made with the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD-D), developed by Zigmond et al. [25] and translated and validated into Portuguese by Botega et al. [26]. This scale was chosen because it does not involve somatic symptoms of depression, which could be confounded with symptoms of hyperglycemia. The HAD-D has 7 items and each is scored from 0 to 3. Bjelland et al. [27], through a systematic literature review, identified a cut-off point of 8 for clinically meaningful depressive symptoms [27].

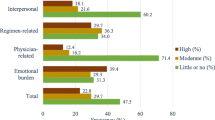

The Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS) was used to assess DD. The DDS was developed by Polonsky et al. [28] and yields a total distress score and four subscales reflecting different sources of distress: emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen related distress and interpersonal distress. The DDS has 17 items and utilizes a 6 point-Likert scale, in which the respondent indicates the presence of a problem for them, ranging from “not a problem” [1] to a “serious problem” [6]. Mean item scores of ≥ 2 are considered clinically meaningful [29]. This scale was validated in Brazil for the Portuguese language by Lima et al. [30].

Empowerment levels were measured by the Diabetes Empowerment Scale short form (DES-SF), developed by Anderson et al. [31]. DES-SF has 8 items, each rated on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). It was translated and validated in a Brazilian sample by Chaves et al. [32]. The DES-SF assesses psychosocial self-efficacy focusing on need for change, developing a plan, overcoming barriers, asking for support, supporting oneself, coping with emotion, motivating oneself, and making diabetes care choices appropriate for one’s priorities and circumstances [33].

Glycemic levels were evaluated by HbA1C, which was measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The patient’s most recent lipid panel results were also recorded. Total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL and triglycerides were measured by commercially available enzymatic techniques.

Chronic microvascular complications of diabetes were assessed through chart review. Diabetic retinopathy was diagnosed based on fundoscopy examinations performed by the University Ophthalmology Department. Nephropathy was diagnosed if two or more urine samples separated by at least 30 days showed albuminuria results above 30 mg/g of creatinine. Neuropathy was diagnosed based on annual clinical examinations performed by the staff physicians at the diabetes clinic.

Seventy patients filled the inclusion criteria and were recruited for this study. Sixty-three patients responded to all the protocol scales. Statistic analysis was performed with these 63 patients. The descriptive analyses of the missing data were included.

Statistical methods

Descriptive analyses were undertaken using means and medians, as appropriate. Differences between groups were assessed by the Mann–Whitney test for numerical variables, by the Chi Square test or by Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Non-parametric tests were used due to the sample size and non normal distribution of some variables. The association between two numerical variables was measured by Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

The association of MDD and other variables on glycemic control was assessed by linear and multivariate regression analysis, using stepwise criteria. All analyses were undertaken using SAS version 9.2 for Windows. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Of the 63 patients, 23 (36.5%) were male, 41.2% had a partner and 80.9% reported an income reaching until 3 Brazilian minimal wage [34]. Sixty two patients were using multiple daily injections and only one was using insulin pump. The total sample mean HbA1C was 10.0% (± 2.0%) (Table 1).

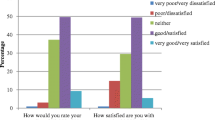

Frequency of MDD, high depressive symptoms and high DD

In this low socioeconomic sample (SES) of T1D adults, the frequency of MDD was 34.9%, based on a structured interview using DSM-5 criteria. The frequency of relevant depressive symptoms was 34.9%, and the frequency of clinically meaningful DD was 57%.

Relationship among MDD, depressive symptoms, DD, and empowerment

The patients with diagnosis of MDD reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms (p < 0.0001). DDS total score was higher in those with MDD diagnosis (p = 0.0003). Likewise the DDS subscale 1 (emotional burden), the DD subscale 3 (regimen distress) and the DDS subscale 4 (interpersonal distress) were higher in those with MDD diagnosis; respectively (p = 0.0033), (p = 0.0026) and (p = 0.0094). The DDS subscale 2 was not different in those with or without MDD (0.43). The empowerment levels were not different in those with or without MDD diagnosis (p = 0.09).

Lastly, depressive symptoms, DD and empowerment levels were significantly intercorrelated (range r = − 0.31 to r = − 0.41).

Women were more likely to receive the MDD diagnosis, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.09). Age did not discriminated between those with and without MDD (p = 0.8). The characteristics of patients with and without MDD are summarized in Table 2.

Table 3 shows the missing data supplementary analyses.

Associations with HbA1C

Empowerment and high DD regimen distress were each significantly associated with HbA1C, according to the univariate linear analyses. Higher HbA1c was associated to lower empowerment levels (p = 0.01) and higher DD regimen distress (p = 0.03). These results are summarized in Table 4.

In multivariate analyses, empowerment levels were linked to glycemic control. Higher HbA1c was associated to lower empowerment levels (beta − 1.11; r-partial 0.09; p-value 0.0126).

The presence of MDD diagnosis and high depressive symptoms were not associated with HbA1C in this expected direction (p = 0.72; p = 0.97, respectively).

Discussion

The current study found a high frequency of MDD, high depressive symptoms, high DD, and low levels of empowerment in this population of low SES T1D adults seen in a tertiary care center in Brazil. The results indicate high depression rates and relatively high psychological distress in this population of T1D patients. These results are supported by other data in literature [1,2,3, 29].

This study also found a positive association between both empowerment levels, DD regimen distress and HbA1C. Low empowerment was significantly associated with high HbA1C. Also, high DD regiment distress was significantly associated with high HbA1C.

Patients with MDD reported higher levels of DD. The higher levels of DD in almost all subscales of DDS showed how the psychological diabetes distress seems to be challenging for the patients affected by MDD. The emotional burden, diabetes regimen distress and interpersonal distress are concerned areas for T1D patients with clinical depression in this population.

The significant intercorrelations among these psychosocial variables suggests how the emotional side of diabetes emerges as a major area of clinical concern among these low-resource adults with T1D. Depressive mood, high management distress and low levels of empowerment are known to be associated with low self-efficacy and feelings of hopelessness and burnout [35,36,37,38,39]. Lack of resources further reduces responsiveness of traditional educational intervention, and creates a cycle of sustained poor management with significant negative clinical consequences over time. The chronicity of T1D, the incessant nature of diabetes care and the demands for management provide a fertile environment for psychosocial problems among most individuals. For patients with low income, such as those enrolled in this study, this challenge can be even more disturbing.

The association between the psychosocial variables and glycemic control demonstrates further how high DD and lack of self-efficacy are tied to disease management and glycemic control. Their interaction over time is most likely circular, rather than linearly causative [40], as mood, self-efficacy and management affect each other over time.

How, then, should a comprehensive care facility that serves low SES T1D adults in tertiary public hospital settings like Unicamp respond to this clinical need? We suggest a two-stage process. First, the results of the current study reinforce the importance of psychosocial assessment in T1D clinical care. The DDS, for example, can provide educators and clinicians with a practical framework for identifying major sources of diabetes-related distress. The four DDS subscales enable the identification of specific sources of distress and allow for targeting specific interventions. Likewise, scores on HAD scale can quantify depressive symptoms and identify the patients at risk for MDD. Mitigating DD and properly addressing depressive symptoms may also facilitate patient engagement in self-management.

Secondly, our results emphasize that educators and clinicians should be trained to utilize strategies to improve empowerment levels of patients. A patient-centered approach provides an effective context to integrate the emotional, social, behavioral and clinical aspects of T1D into more effective and patient-relevant interventions. These strategies include reflection on self-management efforts and experiences, solving problems, identifying and addressing emotional and social problems, asking clinical questions and setting patient-determined behavioral goals [41]. Moreover, a specific focus on the social determinants of health can identify some of the major implications of poverty that affect diabetes management [12, 42, 43]. We suggest that diabetes educators and providers should be familiar with the concepts and implications of these important determinants of diabetes self-management. For example, at Unicamp clinic, the majority of patients use multiple injections of insulin and are provided with only 3 strips/day to monitor blood glucose levels. They have limited access to new technology, like continuous blood glucose sensors and insulin pumps. Other difficulties include the cost of medications, time away from work to receive care, and busy lives with children and family. Therefore, educational programs and care need to consider realistic, problem-based strategies, based on available resources rather than rely exclusively on traditional hospital or outpatient care protocols.

Two strategies, found effective in other low-resource clinical populations, should be considered. First, are peer support programs in which others with T1D are trained to assist patients with disease management, access to resources, and the emotional side of diabetes. The shared support of two individuals with T1D provides an effective medium for intervention and support [44,45,46,47]. This approach has been associated with improved self-care behaviors and metabolic control, decreased emotional burden and lower overall patient healthcare costs [44,45,46], making it cost efficient, in under-resourced clinical settings. Recent research has shown the feasibility of using diabetes educators to train and support peer leaders [47]. A peer support model increases the probability that empowerment-based interventions take place into communities. It also may decrease costs. This is a crucial aspect in underserved populations.

A second, complementary strategy includes the utilization of community health workers (CHWs). CHWs have been useful and effective in enhancing patient and community management of diabetes [46, 48,49,50,]. CHWs are trained to provide healthcare support and have a close understanding of communities they serve through shared ethnicity, culture, language, and life experiences. CHWs may help T1D patients by providing hands-on education, connecting them to community resources, and assisting them to better navigate into medical system [50]. This is specially beneficial in low resource settings, such as Brazil, where T1D patients face multiple challenges, as for example, lack of resources and the cost of transportation. Also, the roles played by CHWs in diabetes self-management are contextually and culturally appropriate.

Our findings have several limitations. First, the study is cross-sectional, such that the direction of causality among the variables included cannot be identified, especially the interaction of the emotional side of diabetes with glycemic control over time. Second, we were unable to assess specific aspects of diabetes management. It would have been helpful to assess the relationships among different aspects of the emotional side of diabetes with specific management tasks, e.g., number of missed boluses and frequency of hypoglycemic episodes. In addition the number of glucose self-monitoring was obtained by self-report. Finally, the results of this study are from a single public tertiary hospital in Brazil. It would have been helpful to evaluate other low SES T1D populations in other Brazilian regions.

Conclusions

The findings of this current study are relevant to diabetes educators, clinicians and researchers who work with low-income T1D patients. The study showed high rates of MDD, depressive symptoms and DD, as well low levels of empowerment in this low SES population. Empowerment and diabetes regimen distress were linked to glycemic control. The results therefore support the need for professionals to prioritize patient psychological and psychosocial concerns when providing clinical education and care.

Focusing exclusively on blood glucose numbers to treat diabetes is incomplete, particularly for highly depressed and distressed populations. Comprehensive education and support for diabetes providers about the psychological and psychosocial aspects of care is crucial, especially in low-resource settings like those at Unicamp.

In addition, we suggest that the implementation of peer support and CHWs programs, focusing on supporting and sustaining patient self-care behaviors in community settings can be very beneficial. These approaches are cost-effective and are especially helpful with underserved populations.

Abbreviations

- T1D:

-

type 1 diabetes

- DD:

-

diabetes related distress

- MDD:

-

major depression disorder

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5th edition

- HAD-D:

-

depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- DDS:

-

Diabetes Distress Scale

- DES-SF:

-

Diabetes Empowerment Scale short form

- HbA1C:

-

glycosylated hemoglobin

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- HDL:

-

high-density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

low-density lipoproteins

- VLDL:

-

very-low-density lipoprotein

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- SES:

-

socioeconomic sample

- CHW:

-

community health worker

References

Trief PM, Xing D, Foster NC, Maahs DM, Kittelsrud JM, Olson BA, Young LA, Peters AL, Bergenstal RM, Miller KM, Beck RW, Weinstock RS, T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Depression in adults in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1563–72.

Berge LI, Øivind Hundal TR, Ødegaard KJ, Dilsaver S, Lund A. Prevalence and characteristics of depressive disorders in type 1 diabetes. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:543.

Barnard KD, Skinner TC, Peveler R. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 1 diabetes: systematic literature review. Diabet Med. 2006;23(4):445–8.

Strandberg RB, Grave M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Peyrot M, Rokne B. Relationships of diabetes-specific emotional distress, depression, anxiety and overall well-being with HbA1c in adult persons with type 1 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:174–9.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–78.

Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky WH, Masharani U, Peters AL, Blumer I, Strycker L. Prevalence of depression in type 1 diabetes and the problem of over-diagnosis. Diabet Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12973.

Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. 2015–2016; 62–8.

American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Supplement 1):S38–50.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes melittus. N Engl J Med. 2003;329:977–85.

Berntein CM, Stockwell MS, Gallagher MP, Rosenthal SL, Soren K. Mental health issues in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Prevalence and impact on glycemic control. Clin Pediatr. 2013;52(1):10–5.

Peyrot M. Levels and risks of depression and anxiety symptomatology among diabetic adults. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:585–90.

Gomes MB, de Mattos Matheus AS, Calliari LE, Luescher JL, Manna TD, Savoldelli RD, Cobas RA, Coelho WS, Tschiedel B, Ramos AJ, Fonseca RM, Araujo NB, Almeida HG, Melo NH, Jezini DL, Negrato CA. Economic status and clinical care in young type 1 diabetes patients: a nationwide multicenter study in Brazil. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50(5):743–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-012-0404-3.

Nguyen AL, Green J, Enguidanos S. The relationship between depressive symptoms, diabetes symptoms, and self-management among an urban, low-income Latino population. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29(8):1003–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.

Verloo H, Meenakumari M, Abraham EJ, Malarvizhi G. A qualitative study of perceptions of determinants of disease burden among young patients with type 1 diabetes and their parents in South India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:169–76. https://doi.org/10.2147/dmso.s102435.

Young-Hyman D, de Groot M, Hill-Briggs F, Gonzalez JS, Hood K, Peyrot M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2126–40.

Rossi MC, Lucisano G, Funnell M, Pintaudi B, Bulotta A, Gentile S, Scardapane M, Skovlund SE, Vespasiani G, Nicolucci A, BENCH-D Study Group. Interplay among patient empowerment and clinical and person-centered outcomes in type 2 diabetes. The BENCH-D study. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(9):1142–9.

Skovlund SE, Peyrot M, DAWN International Advisory Panel. The diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs (DAWN) program: a new approach to improving outcomes of diabetes care. Diabetes Spectr. 2005;18(3):136–42.

Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RIG, Comaschi M, Hermans N, Ishi H, Kokoszka A, Pouwer F, Skovlund SE, Stuckey H, Tarkun I, Vallis M, Wens J, Peyrot M, on behalf of the DAWN2 study group. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN 2): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7):767–77.

Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Empowerment and self-management education. Clin Diabetes. 2004;22(3):123–7.

Funnel MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, et al. Empowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ. 1991;17(1):37–41.

Funnel MM, Anderson RM. Patient empowerment: a look ahead. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(3):454–564.

Anderson RM, Funnell MM. The art of empowerment: stories and strategies for diabetes educators. 2nd ed. Alexandra: American Diabetes Association; 2005.

Anderson B, Funnel MM, Tang TS. Self-management of health. In: Mensing C, editor. The art and science of diabetes self-management education. Chicago: American Association of Diabetes Educators; 2006. p. 43–6.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, Garcia C Jr, Pereira WA. Transtornos de humor em enfermarias de clínica médica e validação de escala de medida (HAD) de ansiedade e depressão. Revista de Saúde Pública. 1995;29:355–63.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Polonsky W, et al. DDS first time. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626–31.

Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky WH, Mullan J. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful? Establishing cut points for the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):259–64.

Curcio R, Alexandre NMC, Carvalho H, Lima MHM. Translation and adaptation of the diabetes distress scale-DDS in Brazilian culture. Acta paul enferm. 2012;25(5):762–7.

Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, Funnell MM, Oh MS. The diabetes empowerment scale-short form (DES-SF). Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1641–3.

Chaves FF, Reis IA, Pagano AS, Torres HC. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the diabetes empowerment scale-short form. Rev Saúde Pública. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006336.

Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, Marrero DG. The diabetes empowerment scale: a measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:739–43.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 2009. www.ibge.gov.br. Accessed 22 July 2015.

Fisher L, Mullan JT, Aren P, Glasgow RE, Hessler D, Masharani V. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycaemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):23–8.

Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control—a meta analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–42.

Lustman PJ, Clouse REJ. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. Diabetes Complicat. 2005;19(2):113–22.

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;60:3278–85.

Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398–403.

Hessler DM, Fisher L, Polonsky WH, Masharani U, Strycker LA, Peters AL, Blumer I, Bowyer V. Research: educational and psychological aspects diabetes distress is linked with worsening diabetes management over time in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13381.

Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: what does it really mean? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1921–2.

Vest BM, Kahn LS, Danzo A, Tumiel-Berhalter L, Schuster RC, Karl R, Taylor R, Glaser K, Danakas A, Fox CH. Diabetes self-management in a low-income population: impacts of social support and relationships with the health care system. Chronic Illn. 2013;9(2):145–55.

Gomes MB, Rodacki M, Pavin EJ, Cobas RA, Felicio JS, Zajdenverg L, Negrato CA. The impact of ethnicity, educational and economic status on the prescription of insulin therapeutic regimens and on glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. A nationwide study in Brazil. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;134:44–52.

Joensen LE, Filges T, Willaing I. Patient perspectives on peer support for adults with type 1 diabetes: a need for diabetes-specific social capital. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1443–51.

Wingate LM, Graffy J, Holman D, Simmons D. Can peer support be cost saving? An economic evaluation of RAPSID: a randomized controlled trial of peer support in diabetes compared to usual care alone in East of England communities. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000328.

Tang TS, Funnell M, Sinco B, Piatt G, Palmisano G, Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Heisler M. Comparative effectiveness of peer leaders and community health workers in diabetes self-management support: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1525–34.

Tang TS, Funnell M, Gillard M, Nwankwo R, Heisler M. Training peers to provide ongoing diabetes self-management support (DSMS): results from a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:160–8.

Lopez PM, Islam N, Feinberg A, Myers C, Seidl L, Drackett E, Riley L, Mata A, Pinzon J, Benjamin E, Wyka K, Dannefer R, Lopez J, Trinh-Shevrin C, Maybank KA, Thorpe LE. A place-based community health worker program: feasibility and early outcomes, New York City, 2015. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3 Suppl 3):S284–9.

Silverman J, Krieger J, Sayre G, Nelson K. The value of community health workers in diabetes management in low-income populations: a qualitative study. J Community Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0491-3.

Bouchonville MF, Hager BW, Kirk JB, Qualls CR, Arora S. EndoEcho improves primary care provider and community health worker self-efficacy in complex diabetes management in medically underserved communities. Endocr Pract. 2018;24(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP-2017-0079.

Authors’ contributions

MSVMS developed and conducted the study, made initial data interpretation and text writing. AMN contributed with statistics suggestions, data interpretation and text review. ACS contributed with text review. LS contributed with text review. EJP contributed to the study design, critical suggestions and analytic review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Lawrence Fisher, Ph.D. and Martha Funnel, MS, RN, CDE for critical suggestions and supervision during several steps in this paper. Maria Cândida Ribeiro Parisi, MD, Ph.D. and Neury José Botega, MD, Ph.D. for suggestions and support. Paulo Oliveira Fanti, who performed statistic analyses and Kristine Ruppert, Ph.D. for support on statistic analyses. We thank the Clinical Research Center, FCM-Unicamp. State University of Campinas, Brazil. We also thank CAPES—Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education—Ministry of Education—MEC, Brazil. M. S. V. M. Silveira: Visiting PhD student, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author can be contacted for any information related to this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University Ethics in Research Committee in December 2015 (Ethics Committee on Research-Unicamp): CAAE number: 50864815.4.0000.5404. All the seventy patients who agreed to participate in this study signed the Consent Form.

Funding

This study received grants from FAEPEX (Fundo de Apoio ao Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão)—Unicamp. State University of Campinas, Brazil.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Silveira, M.S.V.M., Moura Neto, A., Sposito, A.C. et al. Low empowerment and diabetes regimen distress are related to HbA1c in low income type 1 diabetes patients in a Brazilian tertiary public hospital. Diabetol Metab Syndr 11, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-019-0404-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-019-0404-3