Abstract

Aim

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic disease of childhood, with genetic susceptibility and pathological processes such as autoimmunity and autoinflammation, but its pathogenesis is unclear. We conducted a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) using expression interpolation from a large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) dataset to identify genes, biological pathways, and environmental chemicals associated with JIA.

Methods

We obtained published GWAS data on JIA for TWAS and used mRNA expression profiling to validate the genes identified by TWAS. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed. A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was generated, and central genes were obtained using Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE). Finally, chemical gene expression datasets were obtained from the Comparative Toxicogenomics database for chemical genome enrichment analysis.

Results

TWAS identified 1481 genes associated with JIA, and 154 differentially expressed genes were identified based on mRNA expression profiles. After comparing the results of TWAS and mRNA expression profiles, we obtained eight overlapping genes. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the genes identified by TWAS yielded 163 pathways, and PPI network analysis as well as MCODE resolution identified a total of eight clusters. Through chemical gene set enrichment analysis, 287 environmental chemicals associated with JIA were identified.

Conclusion

By integrating TWAS and mRNA expression profiles, genes, biological pathways, and environmental chemicals associated with JIA were identified. Our findings provide new insights into the pathogenesis of JIA, including candidate genetic and environmental factors contributing to its onset and progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the joints, encompassing all forms of chronic inflammatory arthritis of unknown causes and having an onset before the age of 16 years [1]. The reported prevalence varies between 16 and 150 per 100,000 individuals [2]. It typically lasts for longer than 6 months with arthritis present for at least 6 weeks [3, 4]. Joint involvement usually starts with synovitis and the formation of inflammatory tissue, called the pannus, which destroys hyaline cartilage, erodes the bone, and leads to articular destruction and ankylosis [5]. It has been estimated that 37–63% of adults diagnosed with JIA as children maintain active disease [6]. Additionally, children with JIA are at a significant risk for cardiovascular disease in childhood [7]. Although little is known regarding the underlying mechanism, genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases [8]. Therefore, studies of the genetic basis of JIA are necessary to provide a basis and new directions for prevention, early diagnosis, and targeted treatment.

JIA is believed to have a complex molecular basis and is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [9]. Advances in genetic techniques have prompted research on the genetic basis of JIA, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which are a powerful approach to identify genetic loci associated with polygenic complex diseases and traits [10]. However, GWAS is limited in assessing the risk of complex diseases because most single nucleotide polymorphisms identified by this approach are located in non-coding regions [11]. Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) show great promise in interpreting GWAS signatures and are powerful in detecting associations between gene expression levels and complex diseases [12]. TWAS can be used to integrate expression quantitative trait locus (QTL) data with GWAS to identify genes whose regulation is associated with the disease risk [13] and to identify complex trait associations [14]. For example, Gusev et al. used TWAS to identify 69 novel genes in blood and adipose tissue associated with obesity-related traits [15].

Environmental risk factors are strongly associated with the development of autoimmune diseases. In individuals at an increased genetic risk for a disease, environmental or lifestyle factors can lead to early alterations in the immune system and the disruption of self-tolerance, ultimately leading to overt disease [16]. There is strong evidence that chemicals produce biological effects by affecting gene expression. For example, previous studies have revealed that altered gene expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells are associated with occupational benzene exposure [17]. Furthermore, the altered composition of gut microbes, which are affected by environmental conditions, has been implicated in JIA pathogenesis [18]. It has also been shown that sulfur dioxide (SO2) from atmospheric pollution increases the rate of JIA [19]. Therefore, analyzing the effects of chemicals on JIA is crucial.

In this study, candidate genes and biological pathways associated with JIA were identified to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease. Furthermore, we examined the associations between chemicals and JIA based on chemical–gene interaction networks. An overview of the study is provided in Fig. 1.

Data and methods

GWAS data for JIA

GWAS data for JIA were obtained from the literature [20]. In brief, Elena et al. evaluated 4520 UK JIA samples and 9965 samples from healthy individuals using Illumina Infinium CoreExome and Infinium OmniExpress genotyping arrays. Finally, 12,501 individuals were retained in the QC-filtered dataset (3305 cases and 9196 healthy controls). Haplotype phasing and interpolation were performed with the Michigan Interpolation Server using SHAPEIT2 and Minimac3 as well as the Haplotype Reference Consortium reference panel. Simple linear regression using additive genetic models was used to test for genetic associations. Detailed sample characteristics, experimental design, quality control, and statistical analyses are described previously [20].

TWAS of JIA

Common approaches for TWAS (e.g., PrediXcan, TWAS-FUSION, and SMR) can be viewed as forms of instrumental variable analyses with an emphasis on testing causal relationships between gene expression and complex traits [21]. In the present study, FUSION was used to analyze aggregated GWAS data for a TWAS of JIA (http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/). FUSION is a set of tools used to evaluate the association between gene expression and a target disease/phenotype based on pre-calculated gene expression weights and GWAS summary data [15]. Briefly, we used the predictive model implemented in FUSION to calculate the gene expression by combining tissue-specific expression weights with aggregated GWAS results to translate single genetic variant–phenotype associations into gene/transcript–phenotype associations for quantitative evaluations of associations. Gene expression weight panels for precomputation were downloaded from the FUSION website (http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/). All P values were then corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to collect Q values, which represent the minimum false discovery rate (FDR) threshold at which exposure is considered significant. In our study, genes with FDR.P < 0.05 and MODELCV.R2 ≥ 0.01 were considered significant.

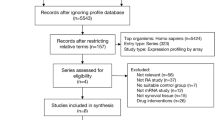

Gene expression profiles for JIA

Gene profiles were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The keywords for inclusion were (1) juvenile idiopathic arthritis, (2) Homo sapiens, and (3) peripheral blood tissue. Datasets with pharmacological stimulation or other interventions were excluded. Finally, we selected two datasets that met the criteria, GSE7753 [22] and GSE11083 [23]. The platform used for both chip datasets was GPL570, Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. The datasets involved 31 patients with JIA and 45 healthy controls. After removing inter-batch effects using the R package “sva” and the combat function [24], a differential gene expression analysis was performed using the “limma” package. Genes with |log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 were screened as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in JIA. The results were visualized using the “ggplot” package. The “ComplexHeatmap” package was used to generate a heatmap [25].

Chemical gene expression annotation dataset

A chemical gene expression annotation dataset was downloaded from the Comparative Toxicology Genomics Database (CTD) (http://ctdbase.org/downloads/), an innovative digital ecosystem that relates toxicological information for chemicals, genes, phenotypes, diseases, and exposure to advance our understanding of human health [26]. CTD integrates four main datasets, namely chemical gene interaction functions, chemical disease associations, genetic disease associations, and chemical element phenotype associations, to automatically construct a hypothetical chemical–gene–phenotype–disease network [27]. A dataset of 1,788,149 chemical–gene pairs annotated with related terms for humans and mice was used by Cheng et al. to generate a set of 11,190 chemical-associated genes [28].

Chemically related gene set enrichment analysis (CGSEA)

A CGSEA was performed to assess the association between chemicals and complex diseases. Briefly, genome-wide pooled data (TWAS pooling) were used to explore the relationship between chemicals and many complex diseases from a genomic perspective. CTD chemical–gene interaction networks and pooled TWAS data were subjected to the weighted Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to explore the relationships between chemicals and JIA [29]. In particular, 10,000 permutations were generated to obtain the empirical distribution of GSEA statistics for each chemical substance, and the p-value was calculated for each chemical substance based on the empirical distribution of CGSEA statistics. Based on the literature, we excluded genomes containing fewer than 10 or more than 500 genes to control for the effect of genome size [30]. The analysis method has been described in detail in a previous study [28].

Functional enrichment analysis

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [31] and Gene Ontology (GO) [32] enrichment analyses of genes identified by the TWAS were performed to identify JIA-related biological processes. Enrichment analyses were performed using the R packages “org.Hs.eg.db” and “clusterProfiler” (https://www.R-project.org/).

Protein–protein interaction network analysis

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were generated using the STRING v11.5 database (STRING, https://string-db.org), requiring a confidence level of 0.15 and generating “active interaction sources” based on a previous study [33]. Cytoscape [34] was used to visualize interaction networks and the plugin Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) [35] was used for analyzing modules.

Results

TWAS of JIA

We identified 1481 genes associated with JIA by TWAS, and there were 225 genes that satisfied FDR.P < 0.05 and MODELCV.R2 ≥ 0.01, including 54, 43, 60, 24, and 44 genes expressed in muscle-skeletal (MS), EBV-transformed lymphocytes (EL), transformed fibroblasts (TF), peripheral blood (NBL), and whole blood (YBL) tissues, respectively. The genes identified by TWAS are shown in a Manhattan plot in Fig. 2. To evaluate tissue specificity as well as co-expressed genes, we performed an overlap analysis of the genes identified by TWAS in different tissues and cells, as summarized in a Venn diagram (Fig. 3). For example, 225 genes identified by TWAS were associated with JIA in TF; three genes were commonly expressed in EL and TF; four significant genes were commonly expressed in EL, TF, and blood (NTR and YFS), and the expression of one gene was common among the four joint categories. The JIA susceptibility gene jointly identified in the four tissues/cells was HLA-DRB1.

Manhattan plot of JIA-associated genes identified by TWAS (colored dots). Each dot represents a gene, the x-axis is the physical location (chromosomal localization), and the y-axis is the -log10 (p-value) of the gene’s association with RA. Significant genes in different tissues/cells are highlighted in different colors. A MS. B YBL. C NBL. D EL. E TF

Common genes identified by TWAS and mRNA expression profiling

Using |log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 as criteria for screening, we obtained 154 DEGs in JIA. The top 20 upregulated and downregulated genes were visualized (Fig. 4).

A The expression signal intensity of each sample detection after inter-batch difference correction, it indicates a good degree of normalization between samples. B The PCA plot after batch difference correction, the difference between the groups is obvious, and the subsequent analysis of variance will have more meaningful results. C A total of 154 differential genes were screened. D The top 20 gene expression of highly expressed genes versus lowly expressed genes in the results

We compared the genes detected by TWAS and by mRNA expression profiling. The following eight common genes were identified by both analyses: ANXA3, GPR146, KCNJ15, ANKRD9, and TMEM158. These 8 common genes are described in Table 1.

CGSEA

We conducted a CGSEA of environmental factors and found that 287 chemical substances were significantly associated with JIA. These significant chemicals included drugs (e.g., levofloxacin), pesticides (e.g., florfenicol), herbal medicines (e.g., difenesin), phenols (e.g., nonylphenol), phthalates (e.g., dicyclohexyl phthalate), heavy metals (e.g., manganese), and air pollutants (1-nitropyrene). The top 50 compounds are listed in Table 2.

Functional exploration of the TWAS-identified genes associated with JIA

We performed GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of 225 genes identified by TWAS and detected 267 GO terms and 37 KEGG terms. Next, 179 GO terms and 36 KEGG terms were screened with p.adjust < 0.05, such as antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen via MHC class I, T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity, rheumatoid arthritis, and human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection. The results are shown in Fig. 5. The top 10 pathways with the lowest p.adjust are summarized in Fig. 6, such as the T-cell receptor signaling pathway and MHC class II protein complex.

Protein–protein interaction network analysis

To identify densely connected regions in the PPI network, we formed eight MCODE clusters with PPI network genes (Fig. 7). The hub genes identified using the MCODE plugins were further evaluated by functional analyses. For example, MCODE1 was associated with autoimmune diseases, MCODE2 was associated with legionellosis and antigen processing presentation, and MCODE3 was associated with negative regulation of NOTCH4 signaling.

Discussion

GWAS is a common method for the screening and identification of candidate genes involved in complex diseases. However, most loci identified by this approach are located in the non-coding regions, making it difficult to explain the relative risk [36]. Therefore, to understand JIA pathogenesis, we performed TWAS using large-scale GWAS data. The main symptoms of JIA are inflammation of the joints as well as extra-articular manifestations, including fever, enlarged lymph nodes, rash, and plasmacytosis [37]; various immune events occur not only in the joints but also on extra-articular mucosal surfaces and primary lymphoid tissues, especially the synovium. Thus, several types of tissues and cells are affected, including the synovial membrane, cartilage, bone, fibroblasts, adipocytes, macrophages, and immune cells [38]. Based on a previous TWAS of RA by Wu et al., we selected MS, EL, TF, NBL, and YBL tissues as gene expression references [38]. We combined the TWAS results with mRNA expression data for JIA to identify candidate genes and performed a pathway enrichment analysis for these genes. Finally, we performed a CGSEA using the pooled TWAS data to identify the environmental factors and chemicals that may be associated with the pathogenesis of JIA.

Integrating TWAS and mRNA expression profiling data revealed several candidate genes associated with JIA, and compared to previous studies, in the present study, we identified some novel genes that may play a potential role in the pathogenesis of JIA, such as ANXA3, GPR146, ANKRD9, and TMEM158. Reportedly, ANXA3 contributes to cancer development via the NF-κB pathway [39]. NF-κB and RANK ligand receptor activator expression in the joints of children with JIA may facilitate the survival of inflammatory cells in the joints [40]. Some studies have shown that GPR146 deficiency reduces lipids and prevents atherosclerosis [41], and the study by Clarke et al. found that genetic susceptibility to juvenile idiopathic arthritis is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors [42], supporting the hypothesis of increased cardiovascular risk in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, suggesting that GPR146 may be associated with the development of JIA. TMEM158 was initially reported as a Ras-induced gene during aging and classified as an oncogenic or tumor suppressor depending on the tumor type [43]. The potential mechanisms involving STAT3 activation mediating TMEM158-driven glioma progression have also been identified, and the inhibitory effect of TMEM158 downregulation on glioma growth has been confirmed [44]. While autoimmune diseases have many similarities with cancer, there are many links and similarities in the pathogenesis of both, so we speculate that TMEM158 may be closely related to the development of JIA.

GO analyses revealed enrichment for several terms, such as T-cell–mediated immune regulation, interferon-gamma–mediated signaling pathway, neutrophil activation, processing and expression of endogenous peptide antigens via MHC class I, processing and expression of antigens via MHC class II, autoimmune thyroid diseases, and rheumatoid arthritis. JIA is characterized by a loss of immune tolerance, and it is believed that the balance between the activity of effector T and regulatory T-cells in the joints is disturbed, leading to the chronic inflammation of the joints and JIA [45]. Our results demonstrate the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity in the pathogenesis of JIA. A life-threatening complication of systemic JIA (SJIA), macrophage activation syndrome (SJIA-MAS), is characterized by a cytokine storm and dysregulated T-lymphocyte proliferation [46]. Our results also confirm that interferons may be involved in JIA development. Several studies have linked antigen processing and expression via MHC class I and MHC class II to the development of JIA, and a recent large-scale study identified the MHC locus as the strongest genetic risk region for JIA [47].

We used an extended classical GSEA with a large-scale GWAS aggregate dataset to detect the associations between environmental chemical substances and JIA and identified 281 chemical substances, including drugs, organic compounds, inorganic compounds, plants extracts, nutrients, phenols, air pollutants, and heavy metals. As a common component used in many consumer products, 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol is a promising amine for use in industrial-scale post-combustion CO, as well as being an atmospheric pollutant [48]. Yavorskyy et al. detected high levels of 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol in the synovial fluid of osteoarthritic knees [49]; thus, it may be related to the onset of joint inflammation to some extent, corroborating our findings. Arbutin is a plant extract often present in skin care products owing to its whitening effect; there is evidence for a combined effect of arbutin and indomethacin on inducing inflammation [50]. As a widespread environmental contaminant with many toxic effects, including roles in endocrine disruption, reproductive dysfunction, immunotoxicity, liver damage, and cancer, 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid amide may contribute to the development of JIA to some extent [51]. β-Naphthoflavone is present in cigarette smoke condensate, and Adachi et al. found that cigarette smoke condensate can lead to AhR-dependent NF-κB activation and activate related pathways, thereby inducing the production of the pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β in synoviocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis [52]. This is consistent with our findings indicating that beta-naphthoflavone is associated with JIA onset.

In this study, we combined TWAS and mRNA expression profiling to identify the candidate genes and biological pathways related to JIA. The combination of these two methods can accurately identify candidate genes. We performed functional enrichment and PPI network analyses of the identified genes and determined biological processes associated with JIA pathogenesis. Finally, we identified several environmental chemicals that may be associated with JIA. Our results provide new insights into the pathogenesis of JIA and its risk factors.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of this study include the following: First, the pooled GWAS data were obtained from the UK Biobank, and the study subjects were mostly from European populations. Thus, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations. Second, some candidate genes for JIA obtained have not been validated by molecular biology experiments; these genes should be evaluated by functional assays in future research.

Conclusion

In summary, we integrated the GWAS dataset of JIA from the UK Biobank to complete TWAS. Then, we further compared the genes identified by TWAS with those identified by mRNA expression profiling and performed GO and KEGG analyses and PPI network construction to identify genes and biological pathways associated with the pathogenesis of JIA. Finally, we performed CGSEA analysis to obtain chemical substances and environmental factors associated with the pathogenesis of JIA. Our results provide a new direction for the study of the mechanisms of JIA at the genetic and molecular levels and new ideas for the chemical environmental factors associated with JIA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) accession number: GSE7753 and GSE11083, and the UK biobank (http://geneatlas.roslin.ed.ac.uk/) fields: 20002.

Abbreviations

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- EL:

-

EBV-transformed lymphocytes

- TF:

-

Transformed fibroblasts

- NBL:

-

Peripheral blood

- YBL:

-

Whole blood

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- TWAS:

-

Transcriptome-wide association studies

- eQTL:

-

Expression quantitative trait loci

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- GTEx:

-

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- PPI:

-

Protein–protein interaction

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

References

Nikopensius T, Niibo P, Haller T, Jagomägi T, Voog-Oras Ü, Tõnisson N, et al. Association analysis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis genetic susceptibility factors in Estonian patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(10):4157–65.

Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369(9563):767–78.

Rostom S, Amine B, Bensabbah R, Abouqal R, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Hip involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(6):791–4.

Hemke R, Kuijpers TW, van den Berg JM, van Veenendaal M, Dolman KM, van Rossum MA, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of unenhanced MRI in the assessment of joint abnormalities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(7):1998–2004.

Argyropoulou MI, Fanis SL, Xenakis T, Efremidis SC, Siamopoulou A. The role of MRI in the evaluation of hip joint disease in clinical subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Br J Radiol. 2002;75(891):229–33.

Zak M, Pedersen FK. Juvenile chronic arthritis into adulthood: a long-term follow-up study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(2):198–204.

Ardalan K, Lloyd-Jones DM, Schanberg LE. Cardiovascular health in pediatric rheumatologic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2022;48(1):157–81.

Wang L, Wang FS, Gershwin ME. Human autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive update. J Intern Med. 2015;278(4):369–95.

Glass DN, Giannini EH. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis as a complex genetic trait. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2261–8.

Canver MC, Lessard S, Pinello L, Wu Y, Ilboudo Y, Stern EN, et al. Variant-aware saturating mutagenesis using multiple Cas9 nucleases identifies regulatory elements at trait-associated loci. Nat Genet. 2017;49(4):625–34.

Xu J, Zeng Y, Si H, Liu Y, Li M, Zeng J, et al. Integrating transcriptome-wide association study and mRNA expression profile identified candidate genes related to hand osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):81.

Liu S, Gong W, Liu L, Yan R, Wang S, Yuan Z. Integrative analysis of transcriptome-wide association study and gene-based association analysis identifies in silico candidate genes associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):13555.

Gusev A, Lawrenson K, Lin X, Lyra PC Jr, Kar S, Vavra KC, et al. A transcriptome-wide association study of high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer identifies new susceptibility genes and splice variants. Nat Genet. 2019;51(5):815–23.

Consortium GT. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369(6509):1318–30.

Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, Bhatia G, Chung W, Penninx BW, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48(3):245–52.

Sparks JA, Costenbader KH. Genetics, environment, and gene-environment interactions in the development of systemic rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2014;40(4):637–57.

McHale CM, Zhang L, Lan Q, Li G, Hubbard AE, Forrest MS, et al. Changes in the peripheral blood transcriptome associated with occupational benzene exposure identified by cross-comparison on two microarray platforms. Genomics. 2009;93(4):343–9.

Qian X, Liu Y-X, Ye X, Zheng W, Lv S, Mo M, et al. Gut microbiota in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: characteristics, biomarker identification, and usefulness in clinical prediction. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):286.

Vidotto JP, Pereira LA, Braga AL, Silva CA, Sallum AM, Campos LM, et al. Atmospheric pollution: influence on hospital admissions in paediatric rheumatic diseases. Lupus. 2012;21(5):526–33.

López-Isac E, Smith SL, Marion MC, Wood A, Sudman M, Yarwood A, et al. Combined genetic analysis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis clinical subtypes identifies novel risk loci, target genes and key regulatory mechanisms. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;80(3):321–8.

Zhang Y, Quick C, Yu K, Barbeira A, Consortium GT, Luca F, et al. PTWAS: investigating tissue-relevant causal molecular mechanisms of complex traits using probabilistic TWAS analysis. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):232.

Fall N, Barnes M, Thornton S, Luyrink L, Olson J, Ilowite NT, et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood from patients with untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis reveals molecular heterogeneity that may predict macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3793–804.

Frank MB, Wang S, Aggarwal A, Knowlton N, Jiang K, Chen Y, et al. Disease-associated pathophysiologic structures in pediatric rheumatic diseases show characteristics of scale-free networks seen in physiologic systems: implications for pathogenesis and treatment. BMC Med Genet. 2009;2:9.

Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, Jaffe AE, Storey JD. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(6):882–3.

Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(18):2847–9.

Davis AP, Grondin CJ, Johnson RJ, Sciaky D, Wiegers J, Wiegers TC, et al. Comparative Toxicogenomics database (CTD): update 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1138–43.

Mattingly CJ, Colby GT, Rosenstein MC, Forrest JN Jr, Boyer JL. Promoting comparative molecular studies in environmental health research: an overview of the comparative toxicogenomics database (CTD). Pharmacogenom J. 2004;4(1):5–8.

Cheng S, Ma M, Zhang L, Liu L, Cheng B, Qi X, et al. CGSEA: a flexible tool for evaluating the associations of chemicals with complex diseases. G3 (Bethesda, Md). 2020;10(3):945–9.

Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(6):1278–83.

Mooney MA, Wilmot B. Gene set analysis: a step-by-step guide. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168(7):517–27.

Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):29–34.

Hill DP, Blake JA, Richardson JE, Ringwald M. Extension and integration of the gene ontology (GO): combining GO vocabularies with external vocabularies. Genome Res. 2002;12(12):1982–91.

Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, et al. STRING 8--a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D412–6.

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–504.

Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2.

Lu Y, Beeghly-Fadiel A, Wu L, Guo X, Li B, Schildkraut JM, et al. A transcriptome-wide association study among 97,898 women to identify candidate susceptibility genes for epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2018;78(18):5419–30.

Cimaz R. Systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(9):931–4.

Wu C, Tan S, Liu L, Cheng S, Li P, Li W, et al. Transcriptome-wide association study identifies susceptibility genes for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthr Res Ther. 2021;23(1):38.

Liu C, Li N, Liu G, Feng X. Annexin A3 and cancer. Oncol Lett. 2021;22(6):834.

Varsani H, Patel A, van Kooyk Y, Woo P, Wedderburn LR. Synovial dendritic cells in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) express receptor activator of NF-kappaB (RANK). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(4):583–90.

Rimbert A, Yeung MW, Dalila N, Thio CHL, Yu H, Loaiza N, et al. Variants in the GPR146 gene are associated with a favorable cardiometabolic risk profile. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(10):1262–71.

Clarke SLN, Jones HJ, Sharp GC, Easey KE, Hughes AD, Ramanan AV, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis polygenic risk scores are associated with cardiovascular phenotypes in early adulthood: a phenome-wide association study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20(1):105.

Huang J, Liu W, Zhang D, Lin B, Li B. TMEM158 expression is negatively regulated by AR signaling and associated with favorite survival outcomes in prostate cancers. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1023455.

Li J, Wang X, Chen L, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Ren X, et al. TMEM158 promotes the proliferation and migration of glioma cells via STAT3 signaling in glioblastomas. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29(8-9):1117–29.

Nijhuis L, Peeters JGC, Vastert SJ, van Loosdregt J. Restoring T cell tolerance, exploring the potential of histone deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:151.

Verweyen EL, Schulert GS. Interfering with interferons: targeting the JAK-STAT pathway in complications of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;61(3):926–35.

Hinks A, Bowes J, Cobb J, Ainsworth HC, Marion MC, Comeau ME, et al. Fine-mapping the MHC locus in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) reveals genetic heterogeneity corresponding to distinct adult inflammatory arthritic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):765–72.

Tan W, Zhu L, Mikoviny T, Nielsen CJ, Tang Y, Wisthaler A, et al. Atmospheric chemistry of 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol: a theoretical and experimental study of the OH-initiated degradation under simulated atmospheric conditions. J Phys Chem A. 2021;125(34):7502–19.

Yavorskyy A, Hernandez-Santana A, Shortt B, McCarthy G, McMahon G. Determination of calcium in synovial fluid samples as an aid to diagnosing osteoarthritis. Bioanalysis. 2010;2(2):189–95.

Matsuda H, Tanaka T, Kubo M. Pharmacological studies on leaf of Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. III. Combined effect of arbutin and indomethacin on immuno-inflammation. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1991;111(4-5):253–8.

Kim SH, Henry EC, Kim DK, Kim YH, Shin KJ, Han MS, et al. Novel compound 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide (CH-223191) prevents 2,3,7,8-TCDD-induced toxicity by antagonizing the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(6):1871–8.

Adachi M, Okamoto S, Chujyo S, Arakawa T, Yokoyama M, Yamada K, et al. Cigarette smoke condensate extracts induce IL-1-beta production from rheumatoid arthritis patient-derived synoviocytes, but not osteoarthritis patient-derived synoviocytes, through aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent NF-kappa-B activation and novel NF-kappa-B sites. J Interf Cytokine Res. 2013;33(6):297–307.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the individuals who participated in, or helped with, our research.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (82072432, 81772410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF and ML collected and processed the data and wrote the article. CY provided language help and writing assistance. LL proofread the article. KX assisted with the grammar changes. PX designed the study. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In addition, ethical approval was not applicable to this study as publicly available data were used for the analysis.

Consent for publication

All co-authors agreed to the publication of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

TWAS results.

Additional file 2:.

mRNA results.

Additional file 3:.

CGSEA results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, R., Lu, M., Yin, C. et al. Identification of candidate genes and pathways associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis by integrative transcriptome-wide association studies and mRNA expression profiles. Arthritis Res Ther 25, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-023-03003-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-023-03003-z