Abstract

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is characterized by increased cardiovascular (CV) mortality. CV events are particularly high in patients with RA-specific autoimmunity, including rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), raising the question whether RA-specific autoimmunity itself is associated with CV events.

Methods

New CV events (myocardial infarction, stroke or death by CV cause) were recorded in 20,625 subjects of the Electricité de France – Gaz de France (GAZEL) cohort. Self-reported RA cases in the GAZEL cohort were validated by phone interview on the basis of a specific questionnaire. In 1618 subjects, in whom plasma was available, RF and ACPA were measured. A piecewise exponential Poisson regression was used to analyze the association of CV events with presence of RA as well as RA-specific autoimmunity (without RA).

Results

CV events in GAZEL were associated with age, male sex, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus (HR from 1.06 to 1.87, p < 0.05). Forty-two confirmed RA cases were identified. Confirmed RA was significantly associated with CV risk increase (HR of 3.03; 95% CI: 1.13–8.11, p = 0.03) independently of conventional CV risk factors. One hundred seventy-eight subjects showed RF or ACPA positivity without presence of RA. CV events were not associated with ACPA positivity (HR: 1.52, 95% CI: 0.47–4.84, p = 0.48) or RF positivity (HR: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.55–2.40, p = 0.70) in the absence of RA.

Conclusions

RA, as a clinical chronic inflammatory disease, but not mere positivity for RF or ACPA in the absence of clinical disease is associated with increased CV risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovitis leading to joint destruction and functional impairment [1]. Prevalence of RA is around 0.5% in Caucasian population [2]. RA development is promoted by a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors that leads to breech of immune tolerance and formation of autoantibodies such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) [1]. Autoimmunity precedes RA by several years (positive predictive value > 96% at 5 years) [3,4,5] and is associated with higher disease activity and structural damage [6, 7].

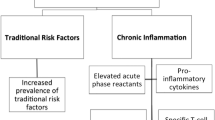

RA is characterized by an increased morbidity and mortality [8,9,10,11]. Besides structural damage and its consequences on disability, increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, including myocardial ischemia and heart failure, has been described in RA [10]. Aside from the consequences from disability and infections, CV disease is responsible for increased mortality in RA [8,9,10,11]. Increased CV risk in RA does not only seem to be explained by standard CV risk factors, but also by chronic inflammation, which accelerates the process of atherosclerosis [12, 13]. This process seems to be independent from the use of concomitant treatments such as corticosteroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which also add to CV risk [14].

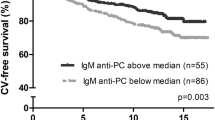

In recent years, several studies suggested that RA with positive RF and/or ACPA presents a higher CV risk [9, 15,16,17,18]. Thus, one may think that RF and ACPA could influence CV risk independently from RA. However, evidence that CV disease may be linked to the presence of autoantibodies, independently from the occurrence of RA, is scarce, and only one study suggested that autoimmunity increases CV risk [15, 16, 19] in a subpopulation of African-American women, but not in all women with positive RF or ACPA [19]. To further explore this question, we made use of a large epidemiological cohort [20,21,22] and separately tested the influence of RA on CV risk as well as the impact of autoantibodies (RF/ACPA) on CV risk, independently of the presence of RA.

Methods

Study population

The GAZEL cohort was started in 1989 and included 20,625 current employees at that time of the French national company of services named “Electricité de France – Gaz de France” [20, 21]. Women were aged between 35 and 50 years and men between 40 and 50 years at inclusion, respectively. Demographic characteristics and a complete medical history were recorded in all subjects at baseline. Thereafter, subjects received an annual questionnaire covering information on a wide spectrum of pathologies, including rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) as well as CV risk factors [20, 21]. In addition, plasma was collected from a fraction of the GAZEL cohort between 2000 and 2005. In 2010, a specific screening questionnaire dedicated to identify patients affected by inflammatory arthritis, including RA, was included in the GAZEL workup.

The GAZEL protocol was approved by the French authority for data confidentiality (‘Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté’) and by the Ethics Evaluation Committee of the ‘Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM)’ (IRB0000388, FWA00005831).

RA diagnosis ascertainment

All subjects who declared to suffer from RA in the 2010 screening questionnaire were included in the study. After having accepted to be contacted, patients were reached by phone and interviewed by an experienced rheumatologist trained for this purpose using a phone questionnaire specifically developed for ascertaining the diagnosis of RA (see Additional file 1). This questionnaire was previously validated on a panel of 102 consecutive outpatients consulting the rheumatology department of Ambroise Paré Hospital (Boulogne-Billancourt, France) for several RMDs (including RA, axial spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis). The questionnaire was administrated by a physician blinded to the patients’ diagnosis, and its sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of RA were of 100% and 89%, respectively (see Additional file 1).

ACPA and RF determination

Aliquots of plasma stored at − 80 °C were used to quantify the presence of ACPA and RF antibodies. Laboratory tests were realized in a specialized research laboratory (Department of Immunology and Internal Medicine, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg) and consisted in IgG ACPA ELISA (Reference Euroimmun EA 1505-9601 G) and IgM-RF ELISA (Reference IBL International RE70341). Cut-off value for ACPA was defined as positive if ≥ 4.6RU/mL, and for RF if ≥ 10 U/mL.

Study timescale

GAZEL cohort began in 1989 with annual updates available for the statistical analysis since then. Blood sample collection was realized only between 2000 and 2005. The baseline year for our analysis was set at the end of the blood sample collection (2005). The number of patients with RA in the whole cohort was calculated using the self-reported diagnosis of RA collected through the questionnaire sent in 2010. These diagnoses were verified using the phone consultation, and we focused our analysis on the RA patients with a disease duration longer than 5 years, i.e., with a confirmed diagnosis of RA at the beginning of the analysis period (2005). Thus, RA diagnosis preceded the occurrence of new CV events. As blood samples were collected between 2000 and 2005 and death causes were available through 2014, the analysis on the occurrence of new CV events was made from the beginning of 2005 through 2014.

Statistical analysis

Clinical and biological parameters (age, sex, CV risk factors, including high blood pressure, smoking habit, alcohol intake, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, death), and the occurrence of CV events, including myocardial ischemia, non-lethal stroke, and death due to any CV cause were reported using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range). The outcome variable was the occurrence of new CV event, including non-lethal myocardial ischemia, non-lethal stroke or death due to CV disease. Non-lethal CV events were self-reported on the annual questionnaires. In these questionnaires, it was recommended to specify if the subject had suffered in the last 12 months of [1] myocardial infarction and [2] stroke. Lethal events were obtained by International Classification of Disease ICD-10 coding of death certificates. Codes of deaths due to CV cause concerned cardiac arrest, atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease, chest pain, myocardial infarction, and all types of strokes. Explicative variables were multiple and concerned RA, autoantibodies (ACPA and RF) and already known CV risk factors. Cut-off values defining risk factors were considered as follows: presence of obesity if body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, alcohol intake if ≥ 14 glasses per week for women and ≥ 21 glasses per week for men (according to World Health Organization (WHO) proposed cut-offs), and corresponding to moderate and high consumption according to the cut-offs proposed by the cohort team; tobacco consumption if the number of pack-years (PY) was ≥ 20, which corresponded to a consumption of 20 cigarettes a day for at least 20 years (and classified as moderate and heavy smoker by the cohort team). High blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and diabetes were also self-reported. Family history of myocardial infarction was considered when it occurred before the age of 60 years (mother) or 50 years (father). We used piecewise exponential Poisson regression, as the data were composed of discrete times of observation [23]. High blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, BMI, and tobacco and alcohol intakes were accounted as time-dependent covariates. Subjects who declared having RA but who were not reached by phone to confirm their diagnosis were excluded from the analyses. We made a comparison between subjects with and without available blood sample.

Results

Identification of CV events

GAZEL cohort enrolled 20,625 subjects, including 5614 women (27.2%) and 15,011 men (72.8%). Mean ± SD age at inclusion was 44.2 ± 3 years. Characteristics of the cohort at the beginning of the analysis period (2005) are reported in Table 1. From 2005 through 2014, a mean of 169 CV events occurred every year in the whole cohort. During this observation period, 1687 subjects in the whole cohort presented a new CV event, 129 of them were lethal and 1558 not lethal.

Identification of RA patients

From the 18,752 subjects still followed in 2010, when the questionnaire on RMDs was administrated, 13,960 replied to that questionnaire. Four hundred twenty-one subjects declared themselves to have RA. Of these, 197 subjects were reached by phone and the RA diagnosis was confirmed in 42 of them and dismissed in 155 (see flowchart Fig. 1). Among the 42 confirmed RA, 30 were men and 12 were women with a mean ± SD age of 61.2 ± 3.4 years. Median RA duration was 9 years (range: 1–43 years). There was no significant difference at baseline (2005) between RA patients and the whole cohort.

Among the RA patients, 13 had plasma sample. Treatment information was available for 30 of them: 87% received at least one disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) (26/30). Among them, 69% had only conventional synthetic DMARDs (18/26), 8% had only biological DMARDs (2/26) and 23% received both (6/26). Patients treated with corticosteroids represented 30% (9/30 patients), 78% of them took < 8 mg per day of prednisone.

Association between RA and CV events

RA was significantly associated with an increased incidence of CV events in both univariable and multivariable analyses, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 3.03 (95% CI: 1.13–8.11, p = 0.03, multivariable analysis) (Table 2). CV events were also associated with established CV risk factors, such as male sex (HR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.5–2.34, p < 0.001), tobacco consumption (HR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.31–1.80, p < 0.001), high blood pressure (HR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.30–1.76, p < 0.001), diabetes (HR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.00–1.56, p = 0.05), dyslipidemia (HR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.03–1.38, p = 0.02), and age (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04–1.09, p < 0.001), but not obesity, which was found significantly associated only in the univariable analysis (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.24–1.79, p < 0.001). In contrast, alcohol consumption was protective, with an HR of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.58–0.88, p = 0.001).

Identification of autoantibody-positive individuals

Plasma samples was available in 1618 subjects of the GAZEL cohort. As compared to the cohort without available plasma samples, subjects with RF or ACPA measurement had a similar prevalence of stroke and myocardial infarction. Also, CV risk factors were comparable between subjects with and without plasma sample except from hypertension (Table 1). With respect to the RA validation questionnaire, 9 RA patients were identified among the subjects with available plasma sample. All were RF or ACPA positive (ACPA+RF+: n = 8; ACPA+RF−: n = 1). Besides, 179 (11.1%) of the 1609 subjects without RA had either positive ACPA and RF (N = 8), ACPA only (N = 37), or RF only (N = 134). Among non-RA subjects, those with either positive ACPA or positive RF differed from the rest of the population only by a higher proportion of men (Table 3). During the observation period, 121 subjects without RA presented a new CV event: 12 had positive RF, 4 positive ACPA, and 105 were seronegative. Among the 9 RA patients, 3 had CV events.

Association between RA-specific autoantibodies and CV events

The association between ACPA and CV risk was studied in non-RA subjects. No association was observed between the occurrence of CV events and ACPA positivity in those subjects (HR: 1.52, 95% CI: 0.47–4.84, p = 0.48, multivariate analysis) (Table 4). Similarly, no association was observed between RF positivity and CV events (HR: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.55–2.40, p = 0.70).

Discussion

In this study, we found that RA, as a clinical disease, but not RA-related autoimmunity was associated with CV events. It is known that RA is associated with two-fold increased risk for CV disease as compared to the general population [24,25,26]. While the overall CV risk in RA patients is based on traditional risk factors as well as autoimmunity related to RA, the increased risk due to RA is usually considered to be due to an increased inflammation and/or autoimmunity [24]. While systemic markers of inflammation have shown to be associated with a higher CV risk [27], other studies have also reported that CV risk is higher in RA patients with ACPA positivity [15,16,17,18], but such observation could be also explained by the correlation between ACPA positivity and RA severity [28], rather than by an independent association with ACPA. Hence, in the RA population, disentangling the effect of autoimmunity on CV risk from that of inflammation is difficult, if not impossible.

The fact that ACPA and RF positivity precedes RA and that some individuals are positive for RF or ACPA without even developing the disease allows to separately assess the role of RA-related autoimmunity and RA, as an inflammatory joint disease, on CV risk [4,5,6]. The analysis of GAZEL individuals that were positive for RF and/or ACPA permitted to directly evaluate the association between ACPA/RF and CV without the influence of arthritis. However, the analysis of these subjects was limited because of the rather low number of subjects with available blood sample, as compared to the whole cohort. Nevertheless, our analysis suggested that RA-related autoimmunity was not associated with an increased risk for CV disease, indicating that systemic inflammation is likely required for precipitating CV events. Under this hypothesis, it is conceivable that effector function of autoantibodies, i.e., Fc- mediated cytokine release, which translates asymptomatic autoimmunity to inflammatory disease might be critical for conveying CV risk [29].

In the GAZEL cohort, traditional risk factors such as male sex, age smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus were independently associated with CV events. Notably, the presence of RA also was significantly associated with CV disease with a HR of 3.0. The strength of the association between CV events and RA is reflected by the fact that the number of ascertained RA cases was rather low in this cohort but nonetheless this association was robust. This observation also supports the robustness of the lack of association between autoantibodies and CV risk as the numbers of autoantibody positive subjects was much higher than the one with RA. The overall low number of ascertained RA cases can be explained by the fact that participants of the GAZEL cohort were mostly males (> 70%). Considering a prevalence of RA of 0.5% in the French population [2], that only up to 1/3 of RA patients being males and that not all subjects with self-reported RA could be validated, the numbers of observed and established RA cases fits the numbers of expected RA cases.

Strength of this study includes the fact that the increased risk of CV events in RA patients as compared to controls was objectively confirmed and that the associations between RA and CV events on one hand, and autoantibodies and CV events in the other were assessed in the same cohort. Another strength is that the ascertainment of RA cases did not rely merely on self-reporting but was confirmed by experienced rheumatologist, using a dedicated questionnaire that was developed and validated for this purpose. A previous study assessed the association between autoantibodies and CV risk in a population-based cohort [30] and found that RF was a predictor of CV events. In this study, there was a higher number of subjects, but RA diagnosis was not confirmed by phone consultation, and CV comorbidities were analyzed only according to baseline characteristics. Concerning ACPA, only a part of the cohort was tested (N = 299), and the association between ACPA and CV events was not adjusted on rheumatic disease. Another study assessing the association between ACPA and RF and CV risk in non-RA patients found that the presence of autoantibodies was associated with CV risk increased in African American women, but the diagnosis of RA was again only based on self-reporting information [19]. A limitation of our study is due to the fact that plasma samples were not available in the entire GAZEL cohort and hence autoantibody data were only obtained in a fraction of the cohort. The fact that we found no significant association between RF and/or ACPA and CV events indicates however that there was no strong association between autoimmunity and CV risk, but does not formally allow to conclude to the absence of such association, considering the rather limited sample-size. On the other hand, subjects with plasma available did not essentially differ from the others with respect to demographic characteristics, CV risk factors and CV events. Furthermore, the robustness of a lack of association between autoantibodies and CV events is supported by the fact that positive association could be observed for RA, despite the fact that the number of RA cases was substantially lower than the number of subjects positively tested for autoantibodies. Finally, as the GAZEL cohort had a high ratio of men, and included subjects with a restricted age range, further studies including a larger number of subjects and a larger women representativeness will be needed to validate our results.

Conclusion

These data suggest that CV risk in RA may rather be dependent on the inflammatory disease itself, while the mere presence of RA-related autoimmunity may not be associated, alone, with CV disease. Thus, the higher risk for CV events in autoantibody-positive RA may be related to a more severe and chronic course of the disease rather than direct effects of autoantibodies on the vessels. These data support the observations that effective control of inflammation may lower CV risk [31, 32].

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Cohortes team of the Unit UMS 011 Paris University - Inserm - Versailles St-Quentin-Paris-Saclay University but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Cohortes team of the Unit UMS 011 Paris University - Inserm - Versailles St-Quentin-Paris-Saclay University responsible for the GAZEL database management.

Abbreviations

- ACPA:

-

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

References

McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2205–19.

Guillemin F. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in France: 2001. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(10):1427–30.

Aho K, Heliövaara M, Maatela J, Tuomi T, Palosuo T. Rheumatoid factors antedating clinical rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(9):1282–4.

Berglin E, Padyukov L, Sundin U, Hallmans G, Stenlund H, Van Venrooij WJ, et al. A combination of autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and HLA-DRB1 locus antigens is strongly associated with future onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(4):R303–8.

Nielen MMJ, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MHMT, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(2):380–6.

van Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, de Jong BA, Breedveld FC, Verweij CL, et al. Autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):709–15.

Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H, Bozec A, Axmann R, Ossipova E, et al. Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(5):1791–802.

van den Hoek J, Boshuizen HC, Roorda LD, Tijhuis GJ, Nurmohamed MT, van den Bos G. a. M, et al. Mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 15-year prospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(4):487–93.

Sparks JA, Chang S-C, Liao KP, Lu B, Fine AR, Solomon DH, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and mortality among women during 36 years of prospective follow-up: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(6):753–62.

Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2008;121(10):S9–14.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Doran MF, Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, et al. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):54–8.

Hannawi S, Haluska B, Marwick TH, Thomas R. Atherosclerotic disease is increased in recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a critical role for inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(6):R116.

Mahmoudi M, Aslani S, Fadaei R, Jamshidi AR. New insights to the mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(3):287–97.

Aviña-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Rahman MM, et al. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2013;52(1):68–75.

Barbarroja N, Pérez-Sanchez C, Ruiz-Limon P, Castro-Villegas C, Aguirre MA, Carretero R, et al. Anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies are implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(12):2706–16.

Arnab B, Biswadip G, Arindam P, Shyamash M, Anirban G, Rajan P. Anti-CCP antibody in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: Does it predict adverse cardiovascular profile? J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4(2):102–6.

Goodson NJ, Wiles NJ, Lunt M, Barrett EM, Silman AJ, Symmons DPM. Mortality in early inflammatory polyarthritis: cardiovascular mortality is increased in seropositive patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(8):2010–9.

Turk SA, Heslinga M, Twisk J, van der Lugt V, Lems WF, van Schaardenburg D, et al. Change in cardiovascular risk after initiation of anti-rheumatic treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(3):513.

Majka DS, Chang RW, Pope RM, Teodorescu MC, Karlson EW, Vu THT, et al. Autoantibodies are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular endpoints in caucasian and african american women in a prospective study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:S711 ((Majka D.S.; Chang R.W.; Liu K.) Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States).

Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Bonenfant S, Chastang JF, Schmaus A, Kaniewski N, et al. Cohort profile: the GAZEL Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(1):32–9.

Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Zins M. Cohort profile update: the GAZEL cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(1):77–77g.

Meneton P, Lemogne C, Herquelot E, Bonenfant S, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. A global view of the relationships between the main behavioural and clinical cardiovascular risk factors in the GAZEL prospective cohort. PloS One. 2016;11(9):e0162386.

Li Y, Panagiotou OA, Black A, Liao D, Wacholder S. Multivariate piecewise exponential survival modeling. Biometrics. 2016;72(2):546–53.

Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJL, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):17–28.

Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, Lehman AJ, Lacaille D. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(9):1524–9.

Nikiphorou E, de Lusignan S, Mallen CD, Khavandi K, Bedarida G, Buckley CD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in early rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Heart Br Card Soc. 2020;106(20):1566–72.

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, Pepys MB, Thompson SG, et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;375(9709):132–40.

Nordberg LB, Lillegraven S, Aga A-B, Sexton J, Olsen IC, Lie E, et al. Comparing the disease course of patients with seronegative and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis fulfilling the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria in a treat-to-target setting: 2-year data from the ARCTIC trial. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000752.

Pfeifle R, Rothe T, Ipseiz N, Scherer HU, Culemann S, Harre U, et al. Regulation of autoantibody activity by the IL-23-TH17 axis determines the onset of autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(1):104–13.

Liang KP, Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Snyder MR, Therneau TM, Roger VL, et al. Autoantibodies and the risk of cardiovascular events. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(11):2462–9.

Arts EE, Fransen J, Den Broeder AA, van Riel PLCM, Popa CD. Low disease activity (DAS28≤3.2) reduces the risk of first cardiovascular event in rheumatoid arthritis: a time-dependent Cox regression analysis in a large cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1693–9.

Singh S, Fumery M, Singh AG, Singh N, Prokop LJ, Dulai PS, et al. Comparative risk of cardiovascular events with biologic and synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(4):561–76.

Acknowledgements

We express our thanks to the Cohort team of the Unit UMS 011 Paris University - Inserm - Versailles St-Quentin-Paris-Saclay University responsible for the GAZEL database management. The GAZEL Cohort Study was funded by EDF-GDF and INSERM and received grants from the “Cohortes Santé TGIR Program,” Agence nationale de la recherché (ANR), and Agence française de sécurité sanitaire de l’environnement et du travail (AFSSET)”.

Funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HG, PA, MB, and MADA analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. GS performed the autoantibodies’ quantification and contributed to the data interpretation and manuscript writing. GM and RSN performed the validation process of diagnosis. MZ and MG are responsible for the GAZEL database management and contributed to the data interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors contributed, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The GAZEL protocol was approved by the French authority for data confidentiality (“Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté”) and by the Ethics Evaluation Committee of the ‘Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM)’ (IRB0000388, FWA00005831).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Details on the specifically dedicated questionnaire for RA diagnosis confirmation and questionnaire translated from French.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gouze, H., Aegerter, P., Said-Nahal, R. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis, as a clinical disease, but not rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoimmunity, is linked to cardiovascular events. Arthritis Res Ther 24, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-022-02722-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-022-02722-z